Полная версия

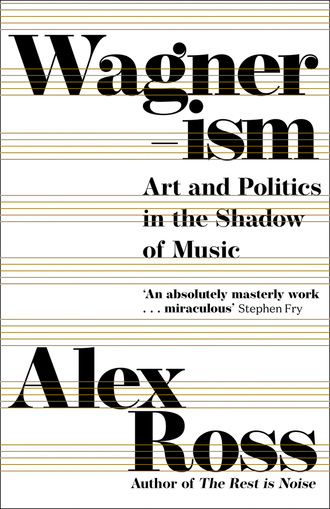

Wagnerism

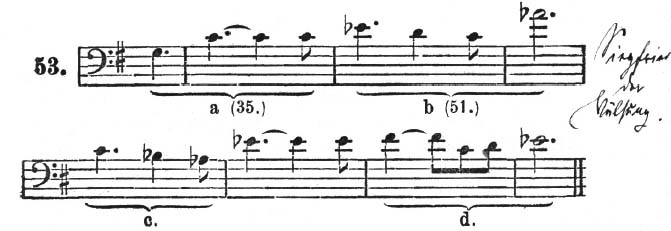

Siegfried’s theme, from Wolzogen’s guide to Ring leitmotifs

At first, Siegfried, the blond hero born of Siegmund and Sieglinde, loomed almost erotically large in Wagner’s imagination. In 1851, he spoke of “the beautiful young man in the shapeliest freshness of his power … the real, naked man, in whom I was able to discern every throbbing of his pulse, every twitch of his powerful muscles.” The strapping youth also has the appearance of a revolutionary, free of sentimental attachments to the extant world. Nietzsche wrote: “His origin already amounts to a declaration of war on morality—he comes into the world through adultery, through incest … He overthrew all tradition, all respect, all fear. He strikes down whatever he does not like.” Shaw called Siegfried “a totally unmoral person, a born anarchist … an anticipation of the ‘overman’ of Nietzsche.”

Siegfried receded in importance as the Ring grew in scope and Wotan moved into the foreground. The god “resembles us to a tee,” Wagner wrote in 1854. Siegfried is more abstract—“the man of the future whom we desire and long for but who cannot be made by us since he must create himself on the basis of our own annihilation.” At times, the composer sounded almost disillusioned with Siegfried, even though his only son bore the hero’s name. “The best part of him is the stupid boy,” Wagner said in 1870. “The man is awful.” Indeed, Siegfried is the most problematic character in the cycle. By design, he lacks complexity: he can seem like an action-movie figure barging into a psychological novel. Stupidity is his tragic flaw. Nonetheless, the entire drama hinges on him.

In 1856, Wagner set about composing Siegfried—the “stupid boy” part of the cycle. It is the archetypal tale of a budding superhero discovering powers he does not yet understand. Siegfried is in the care of Mime, Alberich’s brother, who intends to use the boy to slay the dragon and take the Ring. Siegfried reforges Nothung, Siegmund’s shattered sword, and does the deed. When he tastes the dragon’s blood, he can suddenly understand the discourse of a magical Woodbird, who tells him of Mime’s treacherous nature. Siegfried kills the dwarf and moves on to his next mission: winning a Valkyrie maiden who sleeps within a ring of fire. In the final act, he finds his way blocked by Wotan, who is now disguised as the shadowy Wanderer, his one-eyed face concealed beneath a broad-brimmed hat. The hero breaks the Wanderer’s staff, prances through the magic fire, and meets his destined mate, Brünnhilde.

In the summer of 1857, with two acts of Siegfried drafted, Wagner set the Ring aside in favor of a new project: the romantic tragedy Tristan und Isolde. He was in the throes of an infatuation with the author Mathilde Wesendonck, who was married to his Zurich patron Otto Wesendonck. The love triangle of Tristan mirrored his personal situation. Relations with the Wesendoncks and with his first wife, the actor Minna Planer, reached a point of crisis, and in 1858 he decamped to Venice, rented rooms in a canal-side palace, and buried himself in Tristan. His intention was to produce a more manageable score, one that could earn him the money he needed to finish the Ring. The opera that emerged was so radical in its musical language that it was at first deemed unperformable. After Tristan came Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, a comedy of colossal dimensions. In 1864, work resumed on the first two acts of Siegfried, but not until 1869 did Wagner take up Act III. In the interim, his style had been transformed. At any performance, you feel a jolt when the curtain rises on Act III and the enriched technique of Tristan and Meistersinger comes flooding in, with nine distinct Ring leitmotifs superimposed.

The word “leitmotif” has sown much confusion over the years. Hans von Wolzogen, one of Wagner’s most militant young followers, popularized the term, against the composer’s own wishes. Although Wagner referred to “melodic moments” and “basic motifs” in his work, he criticized Wolzogen for treating such motifs purely as dramatic devices, overlooking their musical logic. In the simplest definition, leitmotifs are identifying sonic tags: when someone talks about the sword, you hear the sword’s theme. Leitmotifs certainly function this way in the Ring, but they are less finished melodies than charged fragments, which transcend their context and gesture forward or backward in time. They not only illustrate the action but indicate what characters are thinking or sensing—or even what they are unable to perceive.

As the Ring proceeds, Wagner handles his leitmotifs in increasingly cavalier, even subversive ways. The motif commonly called “Renunciation of Love” first sounds in Rheingold, as the Rhinemaiden Woglinde explains how the gold can be won. It is heard again in Walküre, when Siegmund is preparing to pull the sword Nothung from the tree. There its purpose is more obscure, and has stirred much speculation. It implies some concealed identity between the lusty hero and the loveless dwarf—and the identity of opposites is a favorite Wagner theme. Even more tellingly, the motif sounds in Götterdämmerung when Brünnhilde tells her sister Waltraute that she will not give up the Ring, because it symbolizes her bond with Siegfried. The Ring’s power has advanced to the stage that love and lovelessness serve its purposes equally.

A psychological study has concluded that neither general musical training nor command of German is necessary for subjects to be able to recognize and recall the leitmotifs. They are superbly designed to lodge in the memory of a broad public, orienting listeners in large-scale compositional structures. Eric Prieto, in his book Listening In, writes that the leitmotif is “not a musical technique at all” but instead a device “borrowed from drama, and dependent on that eminently linguistic procedure, the attribution of a referent to a sound symbol.” Because of its literary nature, the leitmotif has affected literature in turn. Wagnerian authors create networks of phrases that recur across a wide span. Visual artists and filmmakers, likewise, introduce motifs of pattern and color. Although the analogy can become vague to the point of vanishing, artists in many disciplines have respected Wagner’s way of giving continuity to extended forms.

What no artist can imitate with complete success—though Thomas Mann and Proust come close—is the uncanny way leitmotifs operate in later stages of the Ring, bridging expanses of time. The music of previous days resurfaces, as if from another life. From Act III of Siegfried forward, the old motifs are, indeed, the voice of Wagner’s younger self intruding on his mature style. When Siegfried breaks the Wanderer’s staff, the mighty descending figure of Wotan’s spear undergoes a harmonic fracture, breaking into whole-tone intervals. The Spear motif will recur in Götterdämmerung; there it falls into the hands of Alberich’s demonic son Hagen, who dispatches Siegfried with a stab in the back. Having helped to establish identity and personality, leitmotifs also suggest the loss of identity, death itself.

By the time he returned to Siegfried, Wagner had settled in a lakeside house in Tribschen, outside Lucerne. Living with him was Cosima von Bülow, his lover since 1863. The couple remained unmarried until 1870, when Hans von Bülow, Cosima’s first husband, agreed to a divorce. (Minna Wagner had died in 1866.) In the meantime, Cosima had given birth to two illegitimate children, Isolde and Eva. Although she performed the role of helpmate, Cosima was a woman of high intelligence and broad culture, anything but meek in her opinions. That the Bayreuth Festival survived Wagner’s death and became a permanent institution owed everything to Cosima’s skill as a theatrical director, her flair for administration, and her half-ethereal, half-steely charisma. Few women of the period achieved comparable authority. She was also politically reactionary, and, if anything, even more antisemitic than her husband. In 1869, she began keeping a diary, in which she recorded Wagner’s daily utterances and depicted him as a German sage. That formidable document—twenty-one volumes, nearly a million words—is both a rich fund of biographical data and a masterly exercise in image control.

Wagner in Lucerne

“At lunch a philologist, Professor Nietzsche,” Cosima wrote on May 17, 1869. Nietzsche had first met Wagner the previous November, in Leipzig, and succumbed at once to the composer’s personality. “Wagner played all the important parts of Meistersinger, imitating all the voices in very boisterous fashion,” Nietzsche reported. “He is indeed a fabulously lively and fiery man, who speaks very rapidly, is very funny, and makes an intimate party of this sort a total joy.” In private, the glowering Meister of official portraits was antic, ebullient, even clownish. He liked nothing more than to cavort with his dogs, who ruled the household.

In the spring of 1869, the twenty-four-year-old Nietzsche had been appointed professor of classical philology at the University of Basel, which was several hours from Lucerne by train. He came to Tribschen in the hope of renewing his acquaintance with the Meister. It was the eve of Pentecost, Nietzsche recalled—the day the Holy Spirit visits the Apostles. He lingered outside the villa, listening as Wagner tried out chords at the piano. Later, he determined that he had heard the passage of Siegfried in which Brünnhilde sings, “He who woke me has wounded me!” It is a telling moment. Brünnhilde has been confined to the ring of fire for disobeying Wotan’s commands. When Siegfried enters her domain, she initially resists his advances and laments the loss of her Valkyrie powers. She is no helpless maiden awaiting rescue; her pride and intellect remain. When she yields, she does so in the knowledge that this relationship is not a personal matter but a means of world transformation. “Twilight of the gods, darken above,” she sings—the one time that the word “Götterdämmerung” is uttered in the Ring.

When Nietzsche mustered the courage to announce himself, Wagner sent word that he did not wish to be disturbed. The young man was, however, invited for lunch the following Monday. “A quiet and pleasant visit,” Cosima wrote. In early June, Nietzsche returned and spent the night—not any night, but the night that Cosima gave birth to Siegfried Wagner. During Wagner’s remaining years in Tribschen—he moved to Bayreuth in 1872—Nietzsche visited so often that he was given his own room in the house. The friendship deepened into something like a father-son connection. “Strictly speaking, you are, aside from my wife, the one prize I have received in life,” Wagner wrote to his disciple in 1872. Later, in a draft of the preface to the second part of Human, All Too Human, Nietzsche described the relationship as “my only love-affair,” before striking the phrase from his proofs.

Nietzsche grew up in a Lutheran household that cherished the German musical tradition. His father, the pastor of Röcken, a village not far from Leipzig, played the piano and organ in a style that his son characterized as “free variation.” Nietzsche took up piano at an early age, studying repertory from Bach to Schumann. He also composed, in an indistinct Classical-Romantic idiom, and later made the mistake of showing his efforts to the Wagners and their circle. In 1872, Hans von Bülow passed lacerating judgment on Nietzsche’s talent: “From the musical standpoint, your ‘Meditation’ is tantamount to a crime in the moral world. I could discover no trace of Apollonian elements, and as for the Dionysian, I was frankly reminded more of the morning after a bacchanal than of a bacchanal per se.”

At first, Nietzsche regarded the “music of the future” with suspicion. When, in 1866, he studied the score of Walküre, he found “great deformities and defects” alongside “great beauties.” By 1868, though, his interest had intensified into an obsession, as he praised Wagner for possessing qualities that he also attributed to Schopenhauer: “the ethical air, the Faustian scent, cross, death, and grave, etc.” The material of the Ring, and especially the figure of Siegfried, transfixed him. On hearing the preludes to Tristan and Meistersinger, he wrote, “Every fiber, every nerve in me is quivering.” Later, he would compare the experience to taking hashish. Many Wagnerites felt the music to be intoxicating or narcotic in effect. Baudelaire likened it to opium, others to alcohol, morphine, and absinthe.

Nietzsche promptly took on a role that others filled before and after him: that of companion, propagandist, factotum. He stayed at Tribschen during the holidays and carried out duties elsewhere. On one occasion, he was sent to procure caramels and other desserts in Strasbourg; on another, he fetched silk underwear in Basel. There was an element of calculation on both sides. Nietzsche seized the chance to align himself with a star of European culture. Wagner, who lacked strong support in the academic world, knew the value of having a gifted and impassioned young scholar as an ally.

Fulfilling Wagner’s request for a “longer and more comprehensive work,” Nietzsche published his first book, The Birth of Tragedy from the Spirit of Music, in 1872. Its central idea, the duality of the Apollonian and the Dionysian, is one that he had been pondering for a while, but he surely discussed it with the composer, who had his own notions about the Greek gods. In “Art and Revolution,” Wagner associates Apollo with the perfection of the male form, the ordered harmony of Greek architecture, and the swinging rhythm of music. In passing, Wagner comments that Dionysus inspires the tragic poet as he brings forth drama under Apollo’s gaze. A synergy of the two is implied. Hanging in Tribschen was a watercolor of Bonaventura Genelli’s neoclassical painting Bacchus Among the Muses; Nietzsche thought of the picture as he worked on his book. In 1871, Wagner told Nietzsche that the painting, The Birth of Tragedy, and his own work came together in a “remarkable, even miraculous connection.”

Nietzsche also echoes his mentor when he proposes that Greek tragedy gestated in the musical utterance of the chorus. In Opera and Drama, Wagner compares the modern orchestra to the Greek chorus, using the metaphor of the Mutterschooß, the mother’s womb, to describe the function of orchestra and chorus alike. In his 1870 essay on Beethoven, he writes that “out of choral song the drama projected itself onto the stage”—that “out of the spirit of music” the entire Greek order arose. The last phrase passed into the title of The Birth of Tragedy, and the womb image is replicated in the text: “The choral passages that are woven into the tragedy are, in a certain sense, the womb of all of the so-called dialogue, i.e., of the total stage world, the actual drama.”

At almost every turn, however, Nietzsche pushes Wagnerian thought to new rhetorical extremes. His emphasis on Dionysian revelry outpaces the composer’s warier engagement with orgiastic states. His claims on behalf of art are fanatical: “Only as an aesthetic phenomenon is existence and the world eternally justified.” Master and follower diverge most conspicuously on the question of slavery. For Wagner, slavery was a flagrant flaw of Hellenic culture; a Greek revival would require a different social structure, one that would make beauty available to all. Nietzsche repeats certain of these sentiments but never strongly affirms them. In the grip of the Dionysian rite, the slave can achieve freedom, anyone can feel like a god; yet his permanent liberation seems neither possible nor desirable. In an essay on the Greek state, which was dropped from The Birth of Tragedy in its final form, Nietzsche declares that “slavery belongs to the essence of a culture,” its logic binding the masses to the service of a superior, art-creating minority. The intellectual historian Martin Ruehl speculates that Wagner persuaded Nietzsche to omit this material when they discussed the manuscript.

In the last part of The Birth of Tragedy, Nietzsche writes that German music will incarnate “the gradual awakening of the Dionysian spirit.” Amid the degeneracy of contemporary life, one can take comfort in the fact that

the German spirit rests and dreams in an inaccessible abyss, like a knight sunk in slumber, its splendid health, profundity, and Dionysian strength intact; and from that abyss the Dionysian song is wafting up our way, to let us know that this German knight still dreams even now his age-old Dionysian myth in blissfully serious visions. Let no one believe that the German spirit has forever lost its mythical homeland, if it can still understand so clearly the bird voices which tell that homeland’s tale. One day it will find itself awake, in the morning freshness of a tremendous sleep; then it will slay dragons, destroy the spiteful dwarfs, and awaken Brünnhilde—and Wotan’s spear itself shall be unable to block its way!

It is a polemical account of the Ring. Not only Brünnhilde but also Siegfried are cast as sleepers waiting to be awoken. The hero becomes like Friedrich Barbarossa, the Holy Roman Emperor, who was said to lie beneath the Kyffhäuser hills in Thuringia, waiting to rise again. As Benedict Anderson shows in his classic study Imagined Communities, the metaphor of awakening is a commonplace in nationalist discourse, recasting a newly invented entity as a resurrected one. German readers would have related such imagery to the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71 and the crowning of Wilhelm I as Kaiser of a unified Reich. In fact, Nietzsche, who witnessed the war’s carnage as a medical orderly, felt that militarism was eroding the German soul, and argued the point with Wagner, who was in a jingoistic phase. Nietzsche aired those reservations in his 1873 essay on David Strauss, but not in The Birth of Tragedy.

Wagner pronounced himself pleased. “This is the book I have been longing for,” he told Cosima. But it may have impressed him more as a feat of publicity than as a faithful picture of his ideas. Nietzsche thought that Wagner “did not recognize himself in the text.” What is missing is an awareness of Siegfried’s flaws—his gullibility, his rashness, his obliviousness—and a sense of Brünnhilde’s redeeming wisdom. Nietzsche effectively jettisons the Ring’s critique of power. He would later say that Wagner went astray when he lost touch with Siegfried’s vitality and gave in to Wotan’s pessimism: “Everything goes wrong, everything is a disaster, the new world is just as bad as the old one:—Nothingness, the Indian Circe beckons.” The disjunction between Nietzsche and Wagner is visible from the start.

BAYREUTH 1876

“The chief feature of the Wagner district is a great lunatic asylum,” George Bernard Shaw wrote in 1889. “It is a desperately stupid little town.” To call it stupid is unjust, but Bayreuth is certainly a quiet place—a typical provincial German city, with a quaint old center and a fine Baroque opera house. There are no fast trains from metropolitan centers; most travelers must change to a local in Nuremberg, about fifty miles to the southwest. For Wagner, the relative dullness of Bayreuth was a boon. He wanted to locate his festival in a city large enough to accommodate an influx of visitors but not so large as to possess a well-heeled, prejudiced art public of its own. The site had to exist outside of extant cultural networks; it had to be a blank slate.

Wagner had long wished for a new kind of festival experience, through which his audience could escape urban distractions and enter a more receptive frame of mind. There were precedents for such a ritual, such as the Passion Play at Oberammergau, which has been reenacting Jesus Christ’s trial and death at ten-year intervals since 1634. The ultimate model was the Great Dionysia, the civic festival of ancient Athens, which revolved around dramatic performances in the form of tetralogies—three tragedies followed by a satyr play. Wagner set forth his plan in an 1850 letter to Uhlig:

I would erect, in a beautiful meadow near the town, a crude theater of boards and beams, built to my specifications and equipped only with such decor and machinery as is necessary for the performance of Siegfried … At the new year, announcements and invitations to all friends of the musical drama would go out to all the German newspapers, with the offer of a visit to the proposed dramatic musical festival: anyone who responds and travels for this purpose to Zurich would be assured an entrée—naturally, like all the entrées, gratis! In addition, I would invite the young people here, university, choral societies, etc. When everything was in order, I would arrange, under these conditions, three performances of Siegfried in one week. After the third, the theater would be torn down and my score burnt. To those who had enjoyed the thing I would then say: “Now go do the same!”

It would cost ten thousand thalers, Wagner added. Although he soon set aside the immolation of the score, he stuck to this initial scheme for a long time. He often spoke of his theater as a temporary structure, made of light materials. Even at a late stage, he hoped to offer free tickets, so that the experience would be open to all. To be sure, the expense of traveling to Bayreuth would still have been more than most people could bear.

By the later sixties, Wagner was a figure of international renown, his insurgent aura fast dissipating. In 1864, Ludwig II, the teenaged monarch of Bavaria, had come to the composer’s rescue. The king adored Wagner’s music but had his own ideas about architecture, and was not inclined to underwrite a temporary theater in a meadow. When the Romantic-Classical master Gottfried Semper drew up plans for a massive theater in Munich, Wagner called it “nonsensical,” although he approved of Semper’s design for the auditorium itself. The projected cost of the building provoked criticism, adding to the cloud of controversy that surrounded Wagner in Bavaria. Court intrigues and press campaigns forced a retreat to Switzerland. Still, Ludwig sought to make Munich the Wagner capital. Between 1865 and 1870, Tristan, Meistersinger, Rheingold, and Walküre all had their premieres there. Wagner disliked the manner of presentation, and expressed relief when the Munich project came to naught.

Finally, in 1870, Wagner’s eye landed on Bayreuth. The Festspielhaus that rose there, on a hill above the town, was a compromise between the austere 1850 plan and Ludwig’s penchant for luxury. It was a real theater, not a provisional one, yet it was an unostentatious building in an out-of-the-way place. Reviewing the blueprints, Wagner asked for more simplicity, more functionality. “Away with the ornaments!” he wrote on one design. The structure, he said, should be “no more solid than is necessary to prevent it from collapsing.” Seen from the train station, the Festspielhaus looks like a graceful industrial facility rather than a temple of culture. A “rambling, no-style building,” one critic said. The novelist Colette compared it to a gasometer. But it has aged well—a stately pile of brick and wood, framed by stands of trees. Veteran Bayreuthians call the festival complex the Green Hill, as if it were an outgrowth of the park that surrounds it.

The interior was even more jarring to nineteenth-century sensibilities. Traditional opera houses conform to a horseshoe shape, with many of the boxes facing one another—an arrangement conducive to social display. Bayreuth has a fan-shaped array of steeply raked rows, like a section lifted from a Greek amphitheater, so that every seat is angled toward the stage. Two proscenia are nested inside each other, drawing all eyes forward. The pit is set unusually deep, removing the musicians and the conductor from the field of vision. In an acoustical miracle that has never been fully explained, the orchestral sound diffuses richly through the auditorium, even though it must pass through an aperture in front of the stage. Modestly adorned columns line the sides of the auditorium. Hard-backed seats keep the listener awake and alert. In an 1873 essay, Wagner headily summarized the intended effect on the spectator: