Полная версия

Wagnerism

Wagner’s antagonism toward the other, toward an elemental Alberich-like foe, comes to the fore in “Das Judenthum in der Musik,” or “Jewishness in Music,” published under a pseudonym in 1850. That essay contends that Jews have no culture of their own and that leading Jewish composers like Felix Mendelssohn and Giacomo Meyerbeer are stale imitators of tradition and/or agents of capitalist greed. Chillingly, the analogy of a worm-ridden corpse recurs, purporting to evoke Jews’ presence in German society. Relatively few people read this odious document at the time: the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, where it appeared, had a circulation of about eight hundred. Almost two decades later, Wagner republished the essay under his own name, ensuring that it could never be forgotten or excused.

The violence of Wagner’s language in this period is still startling to behold. He writes to his supporter Theodor Uhlig: “Works of art cannot be created at present, they can only be prepared for by means of revolutionary activity, by destroying and crushing everything that is worth destroying and crushing.” He tells Liszt, his most steadfast musical ally, that he has an “enormous desire to commit acts of artistic terrorism.”

Having delivered a kind of polemical artillery barrage—a preview of the assaultive manifesto culture of the early twentieth-century avant-gardes—Wagner returned to his Nibelung material, greatly expanding its scope. First he drafted a prequel to Siegfried’s Death, titled The Young Siegfried. Then he went back further and wrote texts for what became Das Rheingold and Die Walküre (The Valkyrie). The two Siegfried librettos were revised as Siegfried and Götterdämmerung. In the final scenario, Wotan and the gods, representative of a failed monarchical order, are consumed in flames. Wagner told Uhlig that he could conceive of a performance of the entire work “only after the revolution; only the revolution can offer me the artists and listeners I need.” A “great dramatic festival,” in a theater erected on the banks of the Rhine, would “make clear to the people of the revolution the meaning of that revolution, in its noblest sense. This audience will understand me: present-day audiences cannot.” The revolution he has in mind is a future one—the “great revolution of humanity.”

The Ring is grounded not only in politics but also in philosophy. The young Nietzsche called the cycle “an immense system of thought without the conceptual form of thought.” The Rheingold prelude is itself a kind of cosmological proposition. The upwelling of E-flat major is not a creation myth that depends upon a godlike spark, a shout of “Let there be light.” Instead, a world materializes in evolutionary fashion, as in the transmuting organisms studied by Jean-Baptiste Lamarck or the nebularly cohering galactic systems theorized by Immanuel Kant. Early in his career, Kant speculated that the solar system had germinated from a mass of gas and dust. Friedrich Engels saw social implications in that hypothesis: humanity, too, should be seen no longer as a system of fixed relations but as an organism undergoing continual evolution.

The revolutionaries of 1848 leaned heavily on the German philosophical tradition, which, since Kant’s writings of the 1780s, had transformed how thinking beings viewed themselves and the world. As old certainties trembled—monarchic government, religious morality, hierarchies of class—German idealism put forward a new intellectual faith. Kant had enshrined the principle of autonomous reason, of “always thinking for oneself,” as the essence of the Enlightenment. G. W. F. Hegel, Kant’s commanding successor, unveiled a grandiose theory of progress, in which a World Spirit guides history toward a utopian future. To those disconcerted by the condition of evolution and flux, Hegel extended the promise that a perfected world was near.

In the 1830s and ’40s, another wave of thinkers, the Young Hegelians, appropriated the master’s schema, determined to accelerate the World Spirit’s progress. They took aim at religious pieties (David Strauss’s The Life of Jesus Critically Examined, Ludwig Feuerbach’s The Essence of Christianity) and at social inequality (the early economic thought of Marx and Engels). Wagner especially prized Feuerbach’s notion of the “philosophy of the future,” which, the composer later said, promised a “ruthlessly radical liberation of the individual from the bondage of conceptions associated with the belief in traditional authority.” This fixation on futurity—Wagner spoke variously of the artwork of the future, the drama of the future, the theater of the future, the artist of the future, the actor of the future, the religion of the future, the woman of the future, the humanity of the future, and the life of the future—became a favorite target of satirists, but it was a calculated rhetorical device that moved art out of the domain of upper-class entertainment and into the main sociopolitical arena.

Wagner also absorbed the Romantic precept that art should fill the void left by the retreat of traditional religion. Friedrich Schiller, in his 1795 treatise On the Aesthetic Education of Man, declared that humanity achieves freedom through the perception of beauty, that communities find unity through shared aesthetic experience. Schiller saw the advent of an “aesthetic state,” a “joyous realm of play and of appearance.” Friedrich Hölderlin, Friedrich Schlegel, and Friedrich Schelling all held that artistic mythologies could give new spiritual direction to what Max Weber would later call the disenchanted modern world. When Schlegel spoke of a reversion to the “primordial chaos of human nature, for which I know of no lovelier symbol than the motley throng of the ancient gods,” he might have been dreaming of the Ring, even if he had Greek gods in mind. The musicologist Richard Klein summarizes the Wagnerian synthesis: Romantic art-religion is bound to Hegel’s dialectic of progress, creating an aesthetic juggernaut.

Nationalism was a complicating factor. Hegel came to believe that the Spirit would find fulfillment in the modern state, and many shared his view. Johann Gottfried Herder, a member of the Weimar Classical circle that also included Schiller and Goethe, had codified modern nationalism with his thesis that humanity necessarily divides itself into distinct peoples, defined by language and folk traditions. One of philosophy’s great pluralists, Herder had no wish to aggrandize the German Volk at the expense of others. Wagner sounds like Herder when he says, in “Art and Revolution,” that the artist must transcend borders, exhibiting national features merely as a “charm of individual diversity.” More aggressive definitions of Germanness followed. Johann Gottlieb Fichte, in his Addresses to the German Nation (1807–1808), upheld the superiority of German culture, saying that it could bring about a worldwide renewal. The later Wagner fell in with the militant chauvinism that flourished in Fichte’s wake, although the imperial state ultimately disappointed him. Dieter Borchmeyer, in his book What Is German?, describes how nineteenth-century Germany wavered between cosmopolitan and nationalist answers to the titular question. Wagner raised the issue himself and never gave a clear answer.

The metaphysical bravado of German philosophy masked a host of insecurities and fears. Why had the “land of poets and thinkers” failed to form a nation in the political sense? Was Germany’s backwardness a condition to be overcome, or did it preserve premodern values amid dizzying change? Many Romantics, Wagner included, recoiled from nineteenth-century modernity—industrialization, urbanization, mass politics, mass media, the collective onslaught of the age of steam and speed. In the Ring, the Rhine is a resource in danger of exploitation and despoliation. The composer’s urge to heal the break with nature culminates in Parsifal, where the hero says, “Only the spear that inflicted the wound can close it.” In a way, that formula captures Wagner’s own method. His critique of industrial society employs advanced stagecraft and tools of promotion—a culture of spectacle that looks ahead to Hollywood as much as it looks back to ancient Greece. What is modern in his work is intended to heal modernity’s wounds.

Awesome as it is, the Rheingold prelude is something other than an idyll of natural innocence. As Mark Berry argues in Treacherous Bonds and Laughing Fire, a study of the Ring’s political philosophy, the cycle carries no naïve message about the loss of paradise. Wotan’s world is compromised from the start. The motif of the Rheingold—a C-major trumpet fanfare amid shimmering strings—may seem to possess the same triadic purity as the immemorial rushing of the river, but it gives off an illusory, deceitful sheen. And while the Rhinemaidens make a primeval first impression with their watery sound poetry, in Alberich’s vicinity they become sneering sophisticates, mocking the ugly interloper. In The Perfect Wagnerite, Shaw compares them to denizens of high society who disdain a “poor, rough, vulgar, coarse fellow.” Modern productions often depict them as aloof party girls. Their humiliation of the dwarf is cruel, and breeds a resentment that many in the audience may find sympathetic.

In revenge, Alberich takes the gold and fashions the Ring. Significantly, he does not win the prize by force. Wagner has given the Rheingold a peculiar feature, which is not to be found in the medieval sources:

Only he who renounces love’s power,

only he who spurns love’s pleasure,

only he can attain the magic

to wrest the ring from the gold.

In short, power and love are incompatible. If you have one, you cannot have the other. Alberich is willing to make the trade: “Thus I curse love!”

When the gods enter, in the second scene of Rheingold, they present a handsomer picture of the same ugly contradiction. Wotan is locked in a loveless marriage, with Fricka. Inscribed on his spear are the treaties that keep warring factions at bay and preserve his own preeminence. As we later learn, he cut this spear from the World Ash Tree, which withered as a result. Here is more evidence that shadows fell on the Ring universe long before Alberich shuffled in. Wotan has undertaken a massive construction project, Valhalla, which he can ill afford. The giants Fasolt and Fafner have yet to be paid for their work in building it, and they want compensation in the form of Freia, keeper of the apples of eternal youth. When Wotan hears of the Ring, he realizes he can use it to pay off the giants. With Loge, the demigod of fire, Wotan descends to Nibelheim, Alberich’s world, intending to trick the dwarf into giving up the hoard.

During the transition to Nibelheim, Wagner unleashes a gigantic percussion section that includes eighteen anvils—a frightening, futuristic sonority, far removed from the idyll of the Rhine. Shaw seizes on the industrial modernity of the Nibelung domain: “This gloomy place need not be a mine; it might just as well be a match-factory, with yellow phosphorus, phossy jaw, a large dividend, and plenty of clergymen shareholders.” Alberich has multiplied the gold into vast wealth; like Marx’s potentates, he is captive to his capital and takes no pleasure in it. Yet—to adapt an American politician’s quip about the Panama Canal—he stole the gold fair and square, by renouncing love. Wotan makes no such sacrifice, at least consciously, and is therefore a thief of a higher order. As Wagner makes clear in his initial sketch of the Nibelung story, Alberich is “right in his complaints against the gods.” In the final scene of Rheingold, the dwarf delivers his terrible curse upon the Ring, which is also a curse upon Wotan:

Am I free now?

laughing angrily

Truly free?

Then receive my freedom’s

first greeting!

As it came to me through a curse,

so shall this ring be cursed in turn! …

Let all covet

its acquisition,

let none enjoy

its benefit! …

Forfeit to death,

let the coward be fettered by fear:

as long as he lives,

let him die away craving,

the lord of the ring

as the slave of the ring:

till I hold the spoils

in my hand again!

Wotan and Loge try to laugh away this diatribe—“Did you hear his love greeting?”—but the curse kicks in when Fafner kills his brother, Fasolt, in a dispute over possession of the Ring. Wotan begins to realize that his dealings rest on an “evil wage.”

The terms of the political analogy are clear. Wotan is a ruler in the modern mode, willing to allow limited freedoms but prepared to resort to violence. In his mania for treaties, he resembles Klemens von Metternich, the master of the old order. The lesser gods are the aristocracy; the giants are the restless proletariat; Alberich is a self-made capitalist. Loge is like a renegade philosopher-politician who has joined Wotan’s coalition for pragmatic reasons. Many commentators have likened Loge to Bakunin, who, according to Wagner, imagined a world conflagration arising from peasant rebellion. At the end of Rheingold, Loge is tempted to torch Valhalla earlier than scheduled: “They’re hurrying on towards their end, though they think they will last forever … I feel a seductive desire to turn myself into guttering flame.” The fall of the gods is the necessary prelude to a true uprising. “Alles, was besteht, muß untergehen,” Wagner wrote in his 1849 essay “Revolution”—“All that exists must go under.” The words parallel the prophecy of the earth goddess Erda, who warns Wotan, “All that is, ends.”

Rheingold closes with the degraded majesty of the gods’ entrance into Valhalla. Just as Wotan and his clan set foot on the rainbow bridge that leads to their new home, the Rhinemaidens are heard pleading for the return of the gold (“Only down deep is it trusty and true”). Wotan scowls to Loge: “Put an end to their teasing.” Fergus Hume, in his memorial sonnet of 1883, was right to call Wagner “Æschylean”: the scene resembles the ending of Agamemnon. As Clytemnestra and Aegisthus enter the palace of the murdered king, the chorus chants, “Have your way, gorge and grow fat, soil justice, while the power is yours,” to which Clytemnestra replies, “Do not heed their empty yappings.” Both processions are hollow triumphs. False and base is the revelry above. The challenge is to hear the irony in Wagner’s wall of sound: the thrill of the sonority, with its seventeen blaring brass, can trick us into taking the bombast at face value.

DIE WALKÜRE AND METAPHYSICS

In the summer of 1854, Wagner arrived at Walküre, the first full-length opera of the Ring. Settled in Zurich, he composed at a manic pace. By September, he had churned his way through the first act, in which Siegmund and Sieglinde, Wotan’s twin offspring, fall in love without knowing each other’s identity. Despite the scandalousness of the situation, or perhaps because of it, nineteenth-century audiences found these scenes as rousing as any popular romance of the day. The climactic cascade of sensations—Siegmund’s ardent song of love and spring (“Winter’s storms have waned”); Sieglinde’s equally ardent answer (“You are the spring for which I longed”); Siegmund’s drawing of the sword from the tree (“Nothung! Nothung!”); the final orgasmic embrace—is a tour de force of hot-blooded Romantic entertainment.

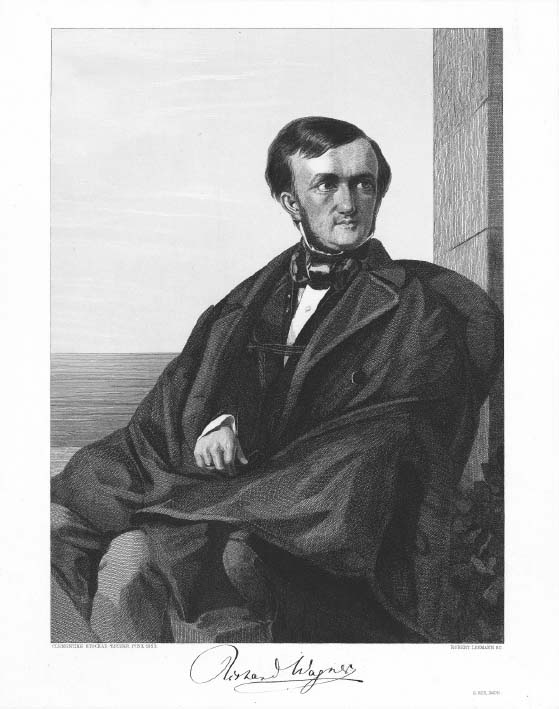

Wagner in Zurich, from Thomas Mann’s picture collection

In the second act, the emotional temperature plummets. Wotan enters in a buoyant mood, convinced that he has found a way to regain the Ring. Having surrendered the gold to Fafner, Wotan cannot revoke the deal, on account of the contracts etched into his spear. Yet the wild human Siegmund would appear to be free of his father’s will and of godly commitments. Surely he can win the Ring from Fafner, who has taken the precaution of turning himself into a dragon. Fricka, Wotan’s disgruntled spouse, proceeds to pick the plan apart. Incestuous love is an outrage, she says, and Siegmund’s independence is a sham: the free man is transparently a pawn. Fricka demands that Wotan stand aside when Sieglinde’s husband, Hunding, comes seeking satisfaction. Wotan descends into a twenty-minute monologue of anguish. The chief of the gods comes to understand his own powerlessness and, beyond that, the inevitability of his end.

Wagner wrote of this scene: “If it is presented as I require—and if all my intentions are fully understood—it is bound to produce a sense of shock beyond anything previously experienced.” First, downward-crawling bassoons, cellos, and a bass clarinet suggest Wotan’s dejection. When his Valkyrie daughter Brünnhilde asks what is wrong, he howls:

O heilige Schmach! O righteous shame! O schmählicher Harm! O shameful sorrow! Götternoth! Gods’ distress! Götternoth! Gods’ distress! Endloser Grimm! Infinite rage! Ewiger Gram! Eternal grief! Der Traurigste bin ich von Allen! I am the saddest of all living things!The alliterations of Stabreim here follow a subtler function, of a kind that Wagner discusses in Opera and Drama. When our ears detect consonant patterns—say, “heilig” (“holy/righteous”) and “Harm” (“sorrow”)—we recognize a bond between seemingly opposed emotions.

The music is titanic. The vocal line dives down jagged intervals—octave, major seventh, minor seventh. The orchestra piles on monolithic dissonances over a cavernous C. The bass note keeps moving down, one false bottom giving way to another, until we reach the basement of the world. Wotan now retells the story of the Ring with a clear view of his own guilt: “I longed in my heart for power … I acted unfairly … I did not return the ring to the Rhine … The curse that I fled will not flee from me now … Let all that I raised now fall in ruins!” Finally, he emits two cries of “Das Ende!”—the first stentorian, the second a whispered gasp. In a bitter epilogue, Wotan bequeaths to Alberich the “worthless splendor of the gods.”

Just before Wagner wrote this music, he made a discovery that reshaped his intellectual landscape. A fellow exile in Zurich was the revolutionary poet Georg Herwegh, who, in 1848, had led an expeditionary force into the Grand Duchy of Baden in support of attempts to found a republic there. Herwegh recommended that Wagner read Arthur Schopenhauer’s The World as Will and Representation. First published in 1818, this lyrical masterpiece of philosophical pessimism initially attracted little attention. In the years when Hegel’s vision of historical progress held sway, Schopenhauer offered a far darker picture of a pain-filled world spinning toward no definite goal. By the early fifties, the pessimist had come into fashion, his world-weariness matching the depleted mood of the postrevolutionary era. At first, Schopenhauer’s imperative of self-abnegation alarmed Wagner, but Herwegh made him realize that all tragedy rests on an awareness of the “nothingness of the world of appearances.”

The World as Will appealed to Wagner not least because it elevated music to a place of preeminence among the arts. In Schopenhauer’s thought, the Will is not simply the striving of the individual but a drive inherent in the universe—an endless need that never finds satisfaction. Music, Schopenhauer says, is the one art form that, rather than copying the outer shell of representation, mimics the operation of the Will itself. The composer reveals the “innermost nature of the world,” and his work “gives the innermost kernel preceding all form, or the heart of things.” The great boon of aesthetic experience, Schopenhauer elsewhere says, is that in replicating the activity of the Will it grants the spectator relief from the Will’s insatiable pressure, by letting him imagine that he has stepped outside of it. “We celebrate the Sabbath of the penal servitude of willing; the wheel of Ixion stands still.”

Nietzsche later smirked that Wagner’s embrace of Schopenhauer was no surprise, given the superpowers that this philosophy bestows on the musician: “Henceforth he became an oracle, a priest, indeed more than a priest, a sort of mouthpiece of the ‘in itself’ of things, a telephone of the beyond.” But the appeal was not simply narcissistic. Wagner saw striking resemblances between Schopenhauer’s work and the Ring in progress. One passage in The World as Will reads like a précis of the opening of Rheingold: “I recognize in the deepest tones of harmony, in the ground-bass, the lowest grades of the will’s objectification, inorganic nature, the mass of the planet.” The ethic of self-abnegation matches Wotan’s acceptance of his powerlessness. Schopenhauer says that only a denial of worldly appearances, a denial of the will to live, can bring peace to the suffering individual. He who overcomes the self will “change his whole nature, rise above himself and above all suffering … and gladly welcome death.” The Wotan of Walküre begins to attain such wisdom, although his behavior lags behind his understanding: “What I love, I must relinquish.”

These ideas had sources older than Schopenhauer. To expose the unreality of the outer world, the philosopher drew not only on the Western intellectual tradition—Plato’s shadows in the cave, Kant’s world of phenomena—but also on Christian asceticism, Buddhism, and Hinduism. The Hindu concept of māyā, the veil of illusion, was paramount. Feuerbach, in his Thoughts on Death and Immortality, had taught that the lust for life is also the lust for death, that “only nothingness can cure being.” True heaven is the “better I of another humanity” that comes into being when the ego withers. The Romantics had long sung in praise of death, dissolution, self-annihilation. Wagner seemed especially open to such thinking after 1848, when his alienation from both political and artistic life became profound. The world is “evil, evil, fundamentally evil,” he wrote to Liszt. “It belongs to Alberich.” Bryan Magee, in his philosophical study The Tristan Chord, proposes that Wagner’s apparent conservative turn resulted from this deeper philosophical transformation: “His significant movement was not from left to right but from politics to metaphysics.” Music itself becomes the metaphysical agent, the way to a “trusty and true” world beyond the veil.

In December 1854, Wagner sent Schopenhauer the text of the Ring, no doubt hoping that the philosopher would recognize it as the work of a kindred spirit. Schopenhauer, who preferred Mozart and Rossini to more modern music, made biting notes in the margins. “Wodan under the slipper!” he wrote next to Fricka’s critique of her husband in Act II of Walküre. The goings-on between the twins caused him obvious distress. Next to the stage instruction that ends the love scene in Act I—“The curtain falls quickly”—Schopenhauer added, “And it’s high time.”

SIEGFRIED DIONYSUS