Полная версия

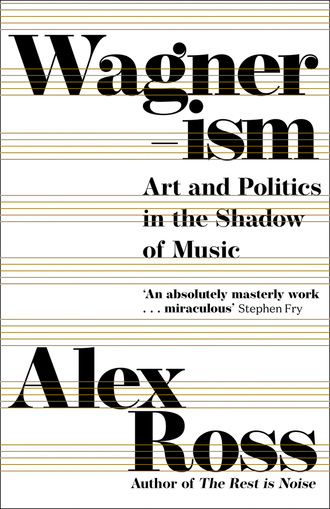

Wagnerism

Once he has taken his seat, he finds himself in a veritable “Theatron”—that is, a space designed for nothing other than looking, and looking where his position points him. Nothing distinctly perceptible comes between him and the image to be looked at—instead only a sense of hovering distance, which results from the architectural arrangement of the two proscenia; in this way, the abstracted image assumes the unapproachability of a dream vision, while the music, sounding spectrally from the “mystic abyss,” like vapors arising from the sacred Ur-womb of Gaia beneath the seat of Pythia, carries him into that inspired state of clairvoyance in which the scenic picture becomes for him the truest reflection of life itself.

This essay bears the imprint of Schopenhauer’s analysis of occult phenomena—clairvoyance, prophetic dreams, encounters with ghosts. The philosopher says that the dreaming or mesmerized mind can find a shortcut to the sphere of the will, where artificial constructs of space and time melt away and glimpses of the future intrude upon the present. Wagner is likewise suggesting that his theater will send its audience into a state of Hellsehen, or clairvoyance. The Pythia was the oracle at Delphi; Bayreuth has a similar function.

In all, Bayreuth was intended to foster a new level of seriousness in the theater public. Spectators should feel themselves disappearing into the work at hand. To assist in that illusion, Wagner planned to have the lights in the auditorium dimmed—again defying an operagoing culture that saw its own finery as part of the spectacle. At the first Ring, adjustable gas lamps failed to operate as planned, resulting in near-total darkness. Although the system was fixed, the idea of Wagnerian gloom took hold. The darkening of theaters actually dates back centuries, but Bayreuth popularized the practice in opera.

Wagner was also keen to discourage the bursts of applause that interrupted standard opera presentations. He did not, however, mandate worshipful silence, as is often claimed. In 1882, at the premiere of Parsifal, he requested that there be no curtain calls after Act II, so as not to “impinge on the impression,” as Cosima wrote. The crowd took this to mean that there should be no applause at all, and total silence greeted the final curtain. Wagner plaintively asked, “Did the audience like it or not?” At a later performance, someone shouted, “Bravo!” during the chorus of the Flower Maidens, and was hissed. That someone turned out to be the composer. Here was an early sign that Wagnerism was taking on a life independent of its creator.

The view from the “mystic abyss”

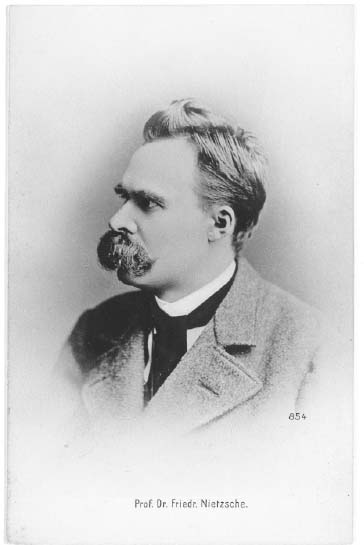

Nietzsche hoped that Bayreuth would be the fulfillment of his Greco-German dreams—a modern festival along Hellenic lines, fusing Apollonian and Dionysian elements, presented before an audience of elite aesthetes. Wagner, for his part, clung to his fantasy of a great popular festival, open to people of all backgrounds. Supporters were building up an international network of Wagner Societies, whose members made advance contributions in exchange for tickets. Through their patronage, Wagner hoped to keep admission free. By 1873, fund-raising was lagging, especially among German notables. Two of the biggest donors were, reputedly, Abdülaziz, the sultan of the Ottoman Empire, and Isma’il Pasha, the khedive of Egypt.

To Nietzsche fell the task of writing an “Exhortation to the Germans,” urging native support. As promotional literature, it left much to be desired, its arguments bending toward the tortured and the delusional: “The German will appear honorable and beneficial to other nations only when he has shown that he is terrifying, and yet through the exertion of his highest and noblest artistic and cultural powers he will make one want to forget that he was terrifying.” Delegates from the Wagner Societies rejected Nietzsche’s work on account of its “bold language,” according to Cosima, though she considered it “very fine.”

Nietzsche’s culminating publicity effort, “Richard Wagner in Bayreuth,” was published in July 1876, just before the festival opened. The tone is portentous, at times preposterous: “When on that day in May 1872, in pouring rain and under dark skies, the cornerstone was laid on that hill in Bayreuth, Wagner rode back to the city with some of us; he was silent and for a long time turned his gaze inward with a look that would be impossible to describe in words.” We are told that Wagner breathes in the “sublime and the ultra-sublime,” that he provides “the supreme model for all art in the grand manner,” that Tristan is “the true opus metaphysicum of all art.” Bayreuth was to be a gathering of chosen apostles, as on that rainy day in 1872, which, Nietzsche solemnly recorded in his notebooks, also fell in the period of Pentecost. At the same time, somehow, the festival would welcome the masses, since Wagner’s art “no longer even recognizes the distinction between cultivated or uncultivated.”

Even as he was manufacturing hype, Nietzsche was inwardly pulling away. The Wagners’ move to Bayreuth led to emotional as well as physical distance. The bustle of the nascent festival made for a dispiriting contrast to the otherworldly idyll on Lake Lucerne. Initial notes for the Bayreuth essay, from 1874, show smoldering skepticism:

If Goethe is a displaced painter and Schiller a displaced orator, then Wagner is a displaced actor.

W.’s youth is that of a many-sided dilettante who seems destined to come to nothing. In an absurd way, I often have doubted whether W. has musical talent.

W. has a domineering character, only then is he in his element … the inhibition of this drive makes him immoderate, eccentric, obstreperous.

W. gets rid of all his weaknesses by imputing them to his age and his adversaries.

Nietzsche remains admiring of the musical achievement, its “unity in diversity,” but he is hostile to the public, theatrical nature of Wagner’s enterprise.

The 1876 festival drew many glittering names. Kaiser Wilhelm I greeted Wagner by saying, “I never thought you’d pull it off.” Dom Pedro II of Brazil, who once expressed interest in becoming Wagner’s patron, made the long journey from Rio de Janeiro. Various dukes, princes, and counts attended—more than two hundred members of the German and Austro-Hungarian aristocracy. Such leading composers as Liszt, Bruckner, Tchaikovsky, Grieg, and Saint-Saëns were present, though Brahms and Verdi stayed away. The crowd included some eminent painters and writers: Hans Makart, Franz von Lenbach, Henri Fantin-Latour, Catulle Mendès.

For the most part, though, well-to-do curiosity-seekers set the tone. Joseph Bennett, one of a hundred or more journalists present, spotted American women “in a chronic state of ecstasy about ‘darling Liszt’” and Frenchmen “meditating epigrams of a withering character.” Tchaikovsky noted that the visitors looked preoccupied, “as if in search of something.” That something turned out to be food, which was in short supply: “Cutlets, baked potatoes, omelettes—all are discussed much more eagerly than Wagner’s music.” Shops were full of tacky merchandise, with Wagner’s face emblazoned on beer mugs, pipe bowls, cigar boxes, and sundry toiletries.

In the end, a festival that professed to shun consumerism all but wallowed in commercial values. As Nicholas Vazsonyi demonstrates in Richard Wagner: Self-Promotion and the Making of a Brand, the composer helped to pioneer modern techniques of mass dissemination and publicity. Wolzogen’s leitmotif guide appeared ahead of the festival. Press releases provided behind-the-scenes anecdotes. The fund-raising system resembled a stock company, a network of investors; the Wagner Societies operated like fan clubs. The buzz of scandal that followed Wagner kept his name in the news—a crucial component of the machinery of celebrity. Somehow, the Ring itself, that radical monument, rose above the noise. Vazsonyi writes: “Wagner’s special skill was the ability to preserve the artistic integrity of his towering works amidst the blaze of commodification to which he in the first place had subjected them.”

Wagner knick knacks at the Reuter Wagner Museum in Eisenach

Nietzsche was appalled. “I no longer recognized anything, I scarcely recognized Wagner,” he wrote in Ecce Homo, remembering the “profound alienation” he felt when he arrived for the final rehearsals of the Ring. “What had happened?—Wagner had been translated into German! The Wagnerian had become the master of Wagner!—German art! The German master! German beer! … Enough; in the middle of it all I left for a couple of weeks.”

The biographical reality is somewhat different. Nietzsche indeed fled to the mountain forest resort of Klingenbrunn, but he was there for only about a week. He went mainly because of his chronic ill health, which included eye problems, piercing headaches, and attacks of vomiting. Sitting for extended periods in a theater was all but unbearable for him. Most likely, he was suffering from a hereditary neurological or vascular disorder; his father, who died at the age of thirty-six, showed similar symptoms. Nonetheless, Nietzsche could not stay away from what he called the “liquid gold” of Wagner’s orchestra, and he returned to Bayreuth in time for the first public performances, August 13–17.

If Nietzsche exaggerated his flight from Bayreuth, there is no doubt that he felt estranged from the festivities. Throughout his life, he believed that a philosopher must wage war on existing forms and conventions—“overcome his time in himself.” Bayreuth made it plain that the former pariah Wagner was now an adornment of the age. A crowd of “bored, unmusical” patrons and “idle European riff-raff” traipsed about, using the place for sport. On a personal level, Nietzsche’s intimacy with the composer was slipping away. The French author Édouard Schuré recalled that Wagner displayed “fantastic gaiety” and “exuberant humor” in gatherings at Haus Wahnfried, putting on his customary one-man performances. Nietzsche, in contrast, seemed deflated—“timid, embarrassed, almost always silent,” Schuré wrote.

Once the festival was over, Wagner, too, lapsed into a state of dejection. Despite all of his ingenious promotional tactics, he had lost a great deal of money, and in many ways the productions failed to satisfy him. Cosima wrote: “R. is very sad, says he wishes he could die!” The next time, he told her, everything would be done differently. In blacker moods, he thought to himself, “Never again, never again!” There was even talk of “giving up the festival entirely and disappearing.” Did Wagner sense that he had fallen far short of his old dream of a free festival in a meadow? In any event, he fled south, as if to recapture the Mediterranean glow in which he had first glimpsed his treacherous gold.

NIETZSCHE’S BREAK

The last meeting between Nietzsche and Wagner took place in the fall of 1876, in Sorrento, on the Amalfi Coast. The Wagners were ensconced at the Grand Hotel Vittoria, which looks out at the sea. Nietzsche was staying in humbler quarters a few minutes away, in the company of his former pupil Albert Brenner and the writers Malwida von Meysenbug and Paul Rée. Relations with Richard and Cosima remained outwardly cordial, but the mood was strained. For one thing, the Wagners were suspicious of Rée, because of his Jewish heritage. They also took an intrusive interest in their friend’s medical issues. To Otto Eiser, Nietzsche’s doctor, Wagner later offered the observation that he had seen other “young men of great intellectual ability” cut down by similar problems, and that these were often the result of masturbation. Eiser replied with polite skepticism, saying that his patient displayed no such abnormalities. At some subsequent date, word of Wagner’s amateur diagnosis got back to Nietzsche, who was left with the impression that his idol suspected him of “unnatural excesses, with hints of pederasty.”

The immediate cause of the break, however, was a brazen display of independence on Nietzsche’s part. During his stay in Klingenbrunn, in the summer of 1876, he had begun making notes for the book that became Human, All Too Human. The style departs markedly from his earlier published writing. In place of spacious paragraphs and ornate sentences, it proceeds by way of aphorisms and polemics, pithy strikes and sudden swerves.

Sleep of virtue.—When virtue has slept, it will arise refreshed.

Luke 18:14 improved.—He who humbles himself wants to be exalted.

Against originals.—When art clothes itself in the most worn-out materials, we most readily recognize it as art.

This change of voice, inspired in part by Rée’s brisk positivist philosophy, goes hand in hand with an attack on metaphysics. Wagner, after the Ring, turned toward the mystical ritual of Parsifal—a staging of the Schopenhauerian ethic of self-abnegation, with elements culled from the great world religions. Nietzsche veered in more or less the opposite direction.

Human, All Too Human begins with a sweeping refutation of the Romantic sublime. All attempts to grasp some fundamental truth behind the veneer of existence—the Ding an sich, the “thing in itself”—result from a false duality; reality consists of a tangled but ultimately graspable web of historically fluctuating relationships. Later sections pick at the moral pieties that underpin so much of Wagner’s work. Parsifal, following Schopenhauer’s philosophy of compassion, sets forth an ethic of “knowing through compassion”—“durch Mitleid wissend.” Nietzsche, who had read Wagner’s prose draft for the opera as early as 1869, hammers away at that word Mitleid, considering it a badge of weakness. Instead he praises animal urges, the flexing of strength, the exercise of force, even to the point of cruelty. “Culture simply cannot do without passions, vices, and acts of malice.” He goes so far as to say that “temporary relapses into barbarism” can rejuvenate an aging civilization. Wagner and Schopenhauer exude sickness and decadence; Nietzsche stands for power and health.

Wagner goes unnamed in Human, All Too Human, but a number of passages take clear shots at him. “Any degree of levity or melancholy is better than a romantic turn to the past and desertion, an accommodation with any form of Christianity whatsoever”: this is a preemptive critique of Parsifal. “It is in any case a dangerous sign when an awe of oneself comes over any human being”: this is a slap at the Wagner cult. There is even a swipe at Cosima, under the heading “Voluntary sacrifice”: “Nothing that women of significance do for their husbands, if they are men of renown and greatness, does more to make their lives easier than becoming the receptacle, as it were, for the general disfavor and occasional ill humor of other people.” That Nietzsche felt a strong attraction to Cosima had long been a complicating factor.

Nietzsche hoped that Wagner would take the book’s challenge in stride, as part of a back-and-forth between equals. Two copies of Human, All Too Human were sent to Bayreuth in April 1878, with a playful dedicatory poem from “Friedrich the Free-minded of Basel” to “the Meister and the Meisterin.” Cosima wrote: “At noon arrival of a new book by friend Nietzsche—feelings of apprehension after a short glance through it.” On subsequent days she described it as “strangely perverse,” “sad,” and “pitiful,” insisting all the while that she was not reading it. “Evil has triumphed here,” she wrote to a friend.

Wagner was no less dismayed, but he kept on reading, and even gave a lyrical recitation of the book’s ending—the ode to the wanderer, who sees “swarms of muses dancing past him in the mist of the mountains.” Did he feel a lingering fondness for Nietzsche’s thought, foreign as it now seemed? One day Wagner thought of sending Nietzsche a congratulatory telegram on the birthday of Voltaire, who is lionized in Human, All Too Human. This might have been the kind of large-spirited gesture that Nietzsche sought. Cosima talked her husband out of it. Bayreuth maintained a cold façade, and Nietzsche felt a “great excommunication.”

That summer, Wagner published the third part of an essay titled “Public and Popularity.” This work and other writings of his last years appeared in the Bayreuther Blätter, the newly founded magazine of the Bayreuth circle. (Wagner had originally wanted Nietzsche to edit the publication; Wolzogen, the labeler of leitmotifs, took the post instead.) Amid a typically rambling disquisition, Wagner refers to certain philologists and philosophers who have achieved “unbounded progress in the field of criticism of all things human and inhuman.” These individuals enact “pitiless” sacrifices of noble victims; they renounce the worship of genius; they are “astonished that Sunday-morning bells still ring today for a Jew crucified two thousand years ago.” (This answers one of Nietzsche’s jabs at Christianity.) Cosima wrote that her husband had taken on Nietzsche “in such a way that a reader who is not fully in the know will not notice.” The ploy was hardly as subtle as that. The excommunication was now official.

Wagner took special umbrage at Nietzsche’s critique of compassion, which directly contradicted his own philosophy. In the course of stewing over Human, All Too Human, he remarked that the chief characteristic of the Devil was “malice, pleasure in the misfortune of others.” Nietzsche appeared to be extolling such pleasure; Wagner thought himself to be taking the side of the weak, in a Christian spirit. If Nietzsche had been able to debate the question face to face, he might have responded that he was concerned chiefly with the hypocrisy of the compassionate; the ones taking pity find selfish delight in a display of emotion and a sense of power. He might also have noted the limits of Wagner’s love of humanity, particularly with regard to Jews.

In the end, both men harbored impulses that look ominous from the vantage point of the post-Holocaust era. What Wagner disliked in Nietzsche—the pitilessness, the exaltation of power—and what Nietzsche disliked in Wagner—the Teutonic chauvinism, the antisemitism—added up to an approximation of the fascist mentality. Once the better angels of their natures are set aside, Wagner and Nietzsche darkly complete each other in the Nazi mind. Of the two, only Nietzsche had an inkling of what the future held. “I know my lot,” he wrote in Ecce Homo. “One day my name will be linked to the memory of something monstrous—to a crisis like none there has been on earth …”

SIEGFRIED ZARATHUSTRA

Wagner had no direct contact with his former acolyte in his final years. The last chance for a reunion would have been at the premiere of Parsifal, in 1882. Nietzsche told friends that he would go to the festival if he received a personal invitation, but none came. It is likely that Wagner regretted the demise of the friendship. Nietzsche’s sister Elisabeth, who was at Bayreuth that summer, claimed that the composer said to her, “Tell your brother that since he left me I am alone.” But public concessions were not in Wagner’s nature. Nietzsche was reduced to monitoring events through intermediaries. “The old sorcerer [Zauberer] has had another tremendous success, with old men sobbing, etc.,” he wrote to his amanuensis Heinrich Köselitz. Nietzsche is presumably the source of the epithet “Sorcerer of Bayreuth.”

Any attempted reconciliation would have been spoiled by the publication that summer of The Joyful Science, which sets aside indirect sniping in favor of frontal assault. Nietzsche accuses Wagner of having misunderstood the philosophy implicit in his own art. Schopenhauer has beguiled him into anti-Jewish blather, into a dubious conflation of Christianity and Buddhism, into an overweening concern for the well-being of animals. (The last shot was carefully aimed, given Wagner’s adoration of his pets.) What is the true philosophy? “The innocence of the highest selfishness; belief in the great passion as a good in itself; in one word, what is Siegfried-like in the countenance of his heroes.” In the next part of The Joyful Science, Nietzsche announces the death of God. Wagner is a fallen Wotan, his staff broken by his substitute son.

The stage is set for the most troublesome of Nietzschean beings, the Übermensch. The word had surfaced in the philosopher’s earlier writings, but usually in a negative sense. The critique of the “cult of the genius” in Human, All Too Human—unmistakably directed at Wagner—isolates the crisis moment when the genius begins to “take himself for something superhuman.” Then, in The Joyful Science, the term acquires a positive connotation. In the section headed “The greatest advantage of polytheism,” Nietzsche advocates a “plurality of norms,” and in so doing mentions “gods, heroes, and superhumans of all kinds, as well as near-humans and subhumans, dwarves, fairies, centaurs, satyrs, demons, and devils.” It sounds like the dramatis personae of the Ring, augmented by Greek and Christian guests. The translation of “Übermensch” as “superman,” popularized by Shaw in his 1903 play Man and Superman, is problematic not only because “Mensch” is gender-neutral but because the word now makes readers think of the brawny comic-book character. Nietzsche’s overman is no caped hero, although he is clearly a superior sort of being, almost a new species.

The Übermensch makes a formal entrance in Thus Spoke Zarathustra, which Nietzsche was writing at the time of Wagner’s death. Zarathustra, the Übermensch’s prophet, appears toward the end of The Joyful Science, preparing to descend from his mountain and undertake his Untergang, his “going under.” The word “Untergang,” which can mean descent, decline, downfall, dissolution, or destruction, is one that Wagner uses repeatedly and indiscriminately. He speaks of the downfall variously of the state, of the gods, of history, of the world, of himself, and, notoriously, of Jews. He wrote to Liszt in 1853: “Mark well my new poem—it contains the world’s beginning and its downfall!” Untergang also has a philosophical history; Hegel’s Logic states that the highest stage of human understanding is that in which its Untergang begins. So Zarathustra’s going under is also a going over (Übergang) to new life, to the world of the Übermensch. The words are paired in one of the book’s most celebrated passages:

Mankind is a rope fastened between animal and Übermensch—a rope over an abyss … What is great about human beings is that they are a bridge and not a purpose: what is lovable about human beings is that they are an Übergang and an Untergang.

Roger Hollinrake, in Nietzsche, Wagner, and the Philosophy of Pessimism, argues that both Zarathustra and the Übermensch stem from Wagner. In one passage, Zarathustra sounds very much like the Wanderer of Siegfried—Wotan in disguise—in dialogue with the earth goddess:

WANDERER: Awake! Vala! Vala, awake! From your long sleep I awaken you, slumberer. I summon you forth: Up! Up! Up from the misty chasm, from the depth of night! Erda! Erda! Eternal woman!

ZARATHUSTRA: Up, abysmal thought, out of my depths! I am your rooster and dawn, you sleepy worm: Up! Up! … And once you are awake, you shall remain awake eternally. It is not my manner to wake great-grandmothers from their sleep only to tell them—go back to sleep! … My abyss speaks, I have unfolded my ultimate depth to the light!