Полная версия

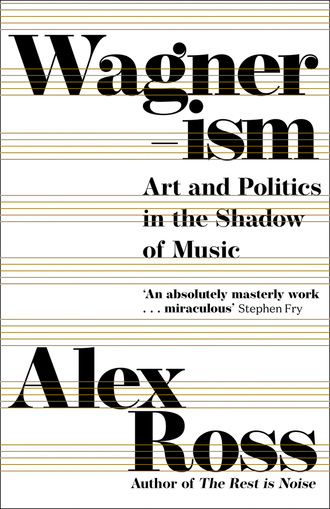

Wagnerism

Wagner’s grave at Wahnfried

He became the Leviathan of the fin de siècle in large part because he was never merely a composer. An idiosyncratic but potent dramatist, he wrote the texts for all of his operas, combining spectacular action sequences with intricate psychological studies. He was a prolific, all-too-prolific essayist and polemicist, whose menagerie of concepts—Gesamtkunstwerk (“total work of art”), leitmotif, “endless melody,” “artwork of the future”—overran intellectual discourse for several generations. He was a theater director and theorist who reshaped the modern stage. Productions at his Festspielhaus in Bayreuth anticipated the advent of the cinema, conjuring legends in the dark. Finally, and fatally, he dabbled in politics, helping to popularize a pseudoscientific form of antisemitism. The sum of all these energies cannot be fixed. “The essence of reality lies in its endless multiplicity,” Wagner wrote in 1854. “Only what changes is real.”

When the term “Wagnerian” first surfaced, it had an ironic ring. In 1847, a critic in the German city of Chemnitz wrote of the “triumph of the Wagnerians, of which we are lucky to have several fine specimens here.” Early on, the word denoted a follower or fan. Later, it marked an artistic quality, an aesthetic tendency, a cultural symptom. The social critic Max Nordau, in his 1892 polemic Degeneration, called Wagnerism “the most widespread, and therefore the most significant, of all present-day aberrations.” Eventually, it became a synonym for grandiose, bombastic, overbearing, or, simply, very long. Things that have been described as Wagnerian include the film Fight Club; the sound of ice breaking; the All-Ireland Gaelic football championship of 1956; the feud between Boeing and the European Aeronautic Defence and Space Company over a $35 billion tanker deal; servings of sausage and schnitzel in German-speaking Switzerland; the roar of a Lamborghini V10; and the monsoon in Mumbai. Similar lists could be made for “leitmotif” and “Gesamtkunstwerk.” The currency of such terms, however spurious their application, testifies to Wagner’s lasting grip.

Even when Wagnerism is defined more narrowly, its meanings multiply. In these pages, it may mean a modern art grounded in myth, after Wagner’s example. It may mean imitating aspects of his musical and poetic language. It may involve combining genres in pursuit of a total artwork. It may take the form of what I call “Wagner Scenes”—tableaux in novels, paintings, and films in which the music is played, discussed, or heard in the background of an interaction, often a seduction. Despite Wagner’s identification with German nationalism, he lived much of his life as a European nomad, and his impact was international in scope. Circa 1900, the composer was like a massive object in space, drawing some entities into its orbit, making others bend just a little as they moved along independent paths. Violent apostasy from Wagner can be Wagnerism inverted, as Nietzsche was the first to demonstrate. Among modernists of the early twentieth century, the agon with Wagner was so widespread as to be almost a distinguishing trait.

This is a book about a musician’s influence on non-musicians—resonances and reverberations of one art form into others. Wagner’s effect on music was enormous, but it did not exceed that of Monteverdi, Bach, or Beethoven. His effect on neighboring arts was, however, unprecedented, and it has not been equaled since, even in the popular arena. He cast his strongest spell on the artists of silence—novelists, poets, and painters who envied the collective storms of feeling that he could unleash in sound.

Dialogues between genres are not always persuasive or coherent. The theatrical visionary Adolphe Appia wrote, “Any attempt to transfer the Wagnerian idea into a work which is not based on music is a contradiction of that very idea.” In a way, this book is a story of failed analogies; the field of Wagnerism is rich in mistranslation, and those ubiquitous Gesamt- and leit- words long ago took on lives of their own. (Wagner used the term “Gesamtkunstwerk” a handful of times in 1849, then set it aside, exclaiming, “Enough of that!”) Yet misreadings can themselves be imaginative acts, as Harold Bloom showed in The Anxiety of Influence. To a surprising degree, an allegedly tyrannical artist becomes a blank screen on which spectators project themselves. Charles Baudelaire wrote to the composer: “You returned me to myself.” Nietzsche, reviewing his youthful effusions, said, “All the psychologically decisive passages speak only of me.”

The salient element of such experiences is that Wagner creates ambiguity and certitude in equal measure. Whatever is flitting through the subject’s mind is amplified and reinforced by a deep engagement with the music. The behemoth whispers a different secret in each listener’s ear. Although Wagner had strong ideas about what his work meant, those ideas were far from consistent, and, in any case, ambiguity was a necessary outcome of his dramatic method, which ultimately rested on the manipulation of myth. “The incomparable thing about myth,” he wrote, “is that it is always true, and its content, through utmost compression, is inexhaustible for all time.” His hoard of borrowed, modified, and reinvented archetypes—the wanderer on his ghost ship, the savior with no name, the cursed ring, the sword in the tree, the sword reforged, the novice with unsuspected powers, and so on—is his most durable legacy.

Early chapters of Wagnerism show a proliferation of mythologies, whether in Nietzsche’s fable of the Übermensch, the poetical arcana of Symbolist Paris, the neo-medieval conceits of the Pre-Raphaelites, or Thomas Mann’s tales of bourgeois decline. The mania gathers momentum not only in opera houses but also in occult shrines and anarchist cells. The middle third explores questions of race, gender, and sexuality. We roam the Wagnerian prairies of Willa Cather and gauge the equivocal responses of modernist writers like James Joyce, Marcel Proust, T. S. Eliot, and Virginia Woolf. The last section crosses the bloodlands of the twentieth century and enters the dreamscape of Hollywood, from The Birth of a Nation to Apocalypse Now. Some of these artists knew the work intimately; others had only glancing knowledge of it. The point is that for several consecutive generations it was omnipresent. The historian Nicholas Vazsonyi writes: “There is no path into the twentieth century—for good or evil—that bypasses Wagner.”

Of the Wagnerisms, the Nazi version is by far the best known. “The term ‘proto-fascist’ was virtually invented to describe Wagner,” the philosopher Alain Badiou has said. The association is not a random accident. Emphasis on “Hitler’s Wagner” in recent decades has been a necessary corrective to the silence that Wagnerites long maintained, whether because of lingering Nazi sympathies or because of a simple wish to avoid the subject. The composer’s worldview, despite its inner conflicts, contained seeds of Nazi ideology. At the same time, the Wagner-to-Hitler narrative has its shortcomings. It is prone to what the literary critic Michael André Bernstein called “backshadowing”—the habit of reading German history as an irreversible march into the abyss. Contemplating the literature of the Holocaust, Bernstein wrote: “We try to make sense of a historical disaster by interpreting it, according to the strictest teleological model, as the climax of a bitter trajectory whose inevitable outcome it must be.” One danger inherent in the incessant linking of Wagner to Hitler is that it hands the Führer a belated cultural victory—exclusive possession of the composer he loved. As early as 1943, the great leftist theater critic Eric Bentley was asking, “Is Hitler always right about Wagner?”

Whatever the merits of the “proto-Nazi” framing, Wagner’s afterlife assumes a tragic shape. An artist who had within his reach the kind of universality attained by Aeschylus and Shakespeare was effectively reduced to a cultural atrocity—the Muzak of genocide. Still, Wagnerism survived the ruination of the Nazi era. In the postwar era, radical directors reinvented the operas onstage. Fantasy epics like The Lord of the Rings, Star Wars, and Game of Thrones rejuvenated Wagner’s mythic devices, consciously or not. The mysticism of Parsifal wafted through the later novels of Philip K. Dick. Musicologists and historians have excavated half-forgotten understandings of the composer, and those alternative Wagnerisms are at the heart of my story: socialist Wagner, feminist Wagner, gay Wagner, black Wagner, Theosophical Wagner, satanic Wagner, Dadaist Wagner, sci-fi Wagner, Wagnerismus, Wagnerismo, Wagnérisme. I am conscious of my limits, in both expertise and language. Nietzsche accused Wagner of dilettantism: in fact, the composer’s legacy is so multifarious that anyone who studies it is a dilettante by default. Writing this book has been the great education of my life.

You need not love Wagner or his music to register the staggering dimensions of the phenomenon. Even lifelong admirers sometimes become exasperated or disgusted with him. As George Bernard Shaw said, in his classic study The Perfect Wagnerite: “To be devoted to Wagner merely as a dog is devoted to his master … is no true Wagnerism.” You can sympathize with Stéphane Mallarmé, who spoke of “le dieu Richard Wagner,” and also accept W. H. Auden’s description of the man as “an absolute shit.” Wagner’s divisiveness, his undiminished capacity to enrage and confuse, is part of his allure. He would have puzzled over the majority of artistic responses to his work, not to mention latter-day styles of opera production. Most of all, though, he would have marveled at the persistence of his music in a world grown alien. Cosima Wagner wrote in her diary: “He believes that after his death they will drop his works entirely, and he will live on in human memory only as a phantom.” In this respect, as in many others, he has been proved triumphantly wrong.

1

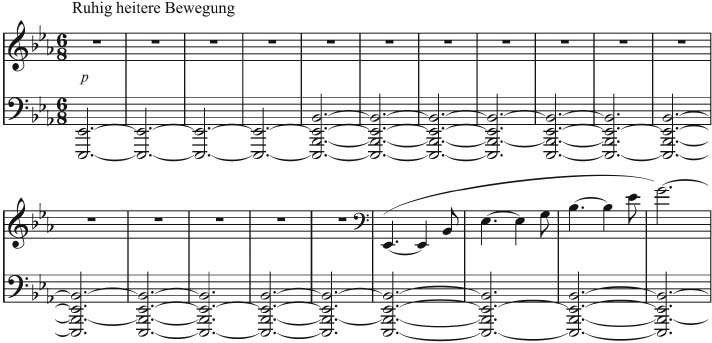

RHEINGOLD

Wagner, Nietzsche, and the Ring

In the beginning was the tone: octave E-flats in the double basses, sustained in a barely audible rumble. Five bars in, bassoons add a pair of B-flats, five steps higher. Together, these notes form the interval of the perfect fifth. Like the fifth that glimmers at the start of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, it is an emanation of primordial nature, the hum of the cosmos at rest. Then eight horns enter one after another, in upward-wheeling patterns, which resemble the natural harmonic series generated by a vibrating string. Other instruments add their voices, in gradually quickening pulses. As the mass of sound gathers and swirls and billows in the air, the underlying tonality of E-flat does not budge. Only after 136 bars—four to five minutes in performance—does the harmony change, tilting toward A-flat. The prolonged stasis engenders a new sense of time, although it is difficult to say what kind of time it is: perhaps an instant passing in slow motion, perhaps eons passing in a blur.

This is the prelude to Das Rheingold, which is itself the Vorabend, the preliminary evening, to the Ring. The orchestra represents the river Rhine, the repository of the magic gold from which a ring of unimaginable power can be forged. In his autobiography, My Life, Wagner relates how the opening came to him while he was staying in La Spezia, on the Ligurian Sea, in September 1853. Resting at his hotel, he fell into “a kind of somnambulistic state,” and the prelude began sounding in his head. Although biographers doubt that it happened exactly that way, we can surmise that the river is not purely German, that it flows from deeper, warmer waters.

“It is, so to speak, the world’s lullaby,” Wagner said. Out of the rocking cradle a universe emerges. The golden triads of Western harmony gestate from a fundamental tone; then language gestates from music. The Rhinemaidens swim up from the depths, singing a mixture of nonsense syllables and German words. Wagner told Nietzsche he had in mind the phrase “Eia popeia,” sung for centuries by mothers to lull their babies.

Weia! Waga! Woge, du Welle, Welter, you wave, walle zur Wiege! surge around the cradle! Wagalaweia! Wallala weiala weia!Wagner is employing a highly stylized version of the old Germanic verse scheme of Stabreim, which is structured around internal alliteration. The affect is epic, the language abstract. The modernists paid heed: T. S. Eliot quotes the Rhinemaidens in The Waste Land, and Joyce has them swim in the river of Finnegans Wake.

The prelapsarian bliss lasts for only twenty-one more bars before the harmony darkens to C minor and Flosshilde warns her fellow maidens that they are neglecting their guardian duties. The Rhine tries to resume its course in the key of B-flat, but it is again tugged into the relative minor. The double basses, having ceased their cosmic drone, play a loping pizzicato. Alberich, the Nibelung dwarf, has entered, his eyes fixed first on the maidens and then on the gold. Wagner sets up a clear duality between the beauty of nature and the malevolent energy of a subhuman outsider. Alberich is the chief antagonist of the Ring, although not necessarily its chief villain. Wotan, the chief of the gods, also lusts after the gold and falls prey to its illusions.

In 1876, in advance of the Ring premiere, Nietzsche, then a kind of intellectual publicist for the composer, issued a pamphlet titled “Richard Wagner in Bayreuth.” Amid much flummery, Nietzsche devises as succinct a synopsis of the cycle as can be found: “The tragic hero is a god who thirsts for power and who, after pursuing all paths to gain it, binds himself through contracts, loses his freedom, and becomes entangled in the curse that is inseparable from power.” Needless to say, the topic is eternally relevant. The story of the fatal ring can always speak to the latest soul-stealing technological marvel, the latest swearing of vengeance, the latest rotting empire. The contradiction at the heart of the project is that the Ring is itself an assertion of power—huge in size, huge in volume, huge in ambition. Wagner criticized monumentality as an artistic value, calling for a vital folk art that spoke to its time instead of gesturing toward posterity. Nonetheless, the monumental and the Wagnerian were fated to become synonymous.

When, in the wake of the Ring, Nietzsche broke with Wagner, he thought of himself as a fugitive slave. Although he disavowed the man, he could not disavow the work. During the twelve years of philosophical activity left to him, he continued to wrestle with the composer’s shadow. In Ecce Homo, he writes: “I actually have it on my conscience that such a high estimation of the cultural value of this movement arose.” The movement is Wagnerei—Wagnerism. Nietzsche is referring to his early gushing on the Meister’s behalf, but it is the later, ostensibly anti-Wagnerian writing that shows the movement in full flower. The rejection of Wagner results only in a new interpretation of Wagner. Such is the infernal logic of his protean presence at the dawn of the twentieth century. As Nietzsche eventually admitted: “Wagner sums up modernity. It can’t be helped, one must first become a Wagnerian.”

THE RING AND REVOLUTION

The revolutionary year 1848, which gave rise to the Ring, shook the old European order but failed to bring it down. In Paris, three days of street protests in February brought about the abdication of King Louis-Philippe and the proclamation of the Second Republic. Similar revolts took place in German-speaking lands, and a national parliament attempted to form in Frankfurt. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels published The Communist Manifesto in London in February; communist, socialist, and anarchist groups organized across the continent. Amid the tumult, counterrevolutionary forces regained the upper hand. The culminating moment—famously described by Marx as historical tragedy repeating itself as farce—was the dissolution of the Second Republic by Louis-Napoléon, Bonaparte’s nephew, at the end of 1851.

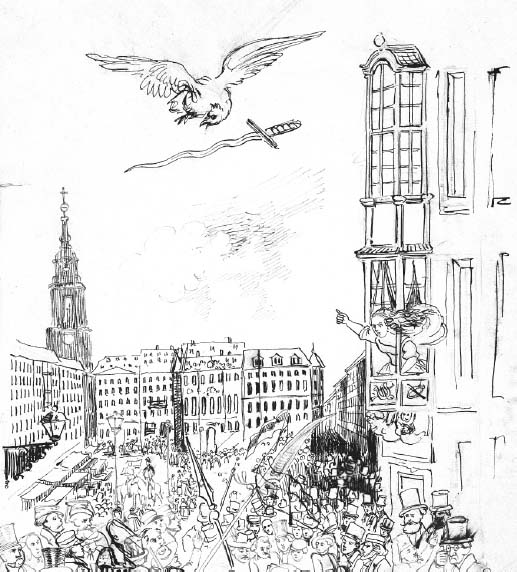

The Dresden uprising of 1849, with the soprano Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient exhorting the crowd from a window

Wagner, then in his mid-thirties, charged into the melee. Since 1843, he had been serving as the Royal Saxon Hofkapellmeister in Dresden, his reputation founded on his sprawling grand opera Rienzi, a dramatization of populist rebellion in fourteenth-century Rome. Over the course of his Dresden tenure, Wagner became increasingly attuned to leftist politics. By June 1848, he was writing poetry about cries of freedom resounding from France. In a fiery speech before the Vaterlandsverein, a democratic-nationalist association, he demanded the obliteration of the aristocracy, the imposition of universal suffrage, the elimination of usury, an enlightened German colonization of the world, and, somehow, the self-reform of the king of Saxony into the “first of the folk, the freest of the free.” Except for the German-nationalist element, these proposals resembled the philosophy of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, who envisioned a society made up of communal units, free of state control but traditional in character.

In the same period, Wagner was delving into old Germanic tales of the hero Siegfried, who slays the dragon Fafnir, wins the dragon’s gold hoard, and dies with a spear in his back. Politics plainly motivated this turn: the gold represents the capitalist enemy, Siegfried a new German nation. More broadly, Wagner became engrossed by the evolution and function of myth. Sometime in 1848, he began writing “The Wibelungs,” an impressively convoluted essay in comparative mythology, which muses on the interrelationship of pagan legends, Christian lore, the Nibelung treasure, the Holy Grail, and historical personalities such as Charlemagne and Emperor Friedrich Barbarossa. What fascinated the composer was how the same stories keep getting told in different guises: light against dark, warmth against cold, hero against dragon.

Wagner’s subsequent interweaving of mythic stories in operatic form caused him to be described—by none other than the anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss—as “the incontestable father of the structural analysis of myths.” The extension of ancient cycles into the present day brings with it an unsettling implication: the same dark, cold, dragon-like adversaries will be present in modern Germany. Ominously, Wagner compares the murder of Siegfried to the Crucifixion, remarking that “we still avenge Christ on the Jews today.”

In the fall of 1848, Wagner emerged with a prose sketch titled “The Nibelung Myth,” outlining a plot roughly equivalent to that of Götterdämmerung. It includes an elaborate backstory of gods, giants, dwarves, heroes, and Valkyries—essentially, the whole of the Ring in a few dense pages. The scenario combines material from various Nordic and Germanic sources—the Poetic Edda, the Prose Edda, and the Vǫlsunga saga of Iceland; the Old Norwegian Þiðreks saga; the German Nibelungenlied; Jacob Grimm’s German Mythology—into an inspired mishmash that owes as much to the composer’s unruly imagination as to the extant sources.

The Ring itself is a new contraption. The old stories make mention of hoards and magic rings, but only in Wagner’s version does the gold yield a weapon of absolute omnipotence. The one vague antecedent is Plato’s Ring of Gyges, which makes the wearer invisible and thereby endows him with “the powers of a god.” Even a just man might misbehave with such a device at his command, Plato suggests. Likewise, Wagner’s Ring bends all to its will. Its companion gadget, the Tarnhelm, enables one to disappear, change shape, or travel far in an instant. It is surely no accident that such magic lore found new life in the late nineteenth century, when technologies of mass manipulation and mass destruction were coming into view.

“The Nibelung Myth” begins not with an image of natural splendor, as in the finished cycle, but with a sinister picture of an infested earth:

Out of the womb of night and death there germinated a people, which lives in Nibelheim (Mist-Home), that is, in gloomy underground chasms and caves: they are called Nibelungs; with shifty, restless activity they burrow (like worms in a dead body) in the bowels of the earth … Alberich seized the bright and noble Rhinegold, abducted it from the water’s depths, and with great and cunning art forged from it a ring, which gave him supreme power over his entire kin … Alberich strove for domination of the world and everything contained in it.

The good-versus-evil duality breaks down, though, when Wagner makes the noble gods complicit in the general corruption. “The peace by which they achieved domination is not grounded in reconciliation; it is accomplished through force and cunning. The intent of their higher world order is moral consciousness, but the wrong they are pursuing adheres to themselves.” In this early version, Wotan survives the upheaval, like the reformed monarch in Wagner’s Vaterlandsverein speech, and Alberich is set free with the rest of humanity.

Wagner fleshed out the story in a prose draft titled Siegfried’s Death. He then set the project aside and engaged in the most intense political activity of his life. In May 1849, Dresden revolutionaries rose up in protest of anti-constitutional actions by the Saxon king, and Wagner joined them, generating propaganda, helping to obtain arms, and sending signals from the tower of the Kreuzkirche. He was often at the side of the future anarchist Mikhail Bakunin, who had long-standing ties to German radical circles. According to one witness, Wagner fell into a paroxysm of rage, shouting, “War and always war.” The day after the Dresden opera house was set ablaze, a street fighter supposedly called out, “Herr Kapellmeister, the beautiful divine spark of joy has ignited.” This was an allusion to the “Ode to Joy” in Beethoven’s Ninth, which Wagner had conducted a few weeks earlier: “Freude, schöner Götterfunken.”

In the aftermath, both Bakunin and Wagner’s friend August Röckel were captured, convicted, and condemned to death, though the sentences were later commuted to prison terms. Wagner would probably have met the same fate if he had not eluded the authorities and made his way to Zurich, where he remained until 1858. For several years, he all but stopped composing and threw himself into the writing of essays, manifestos, and dramatic texts. In “Art and Revolution,” he assails commercial interests, saying, “Our god is money, our religion is making money.” Because of the false collectivity of capitalist society, artists must join the revolutionary opposition. In “The Artwork of the Future,” he upholds ancient Greek theater as a model for an amalgamation of the arts—the fabled Gesamtkunstwerk. And in the book-length treatise Opera and Drama he sets out the principles that underpin the Ring: a clear, uncluttered projection of the text; the use of recurring motifs to illustrate characters, concepts, and psychological states; the deployment of the orchestra as a medium of foreboding and remembrance.