Полная версия

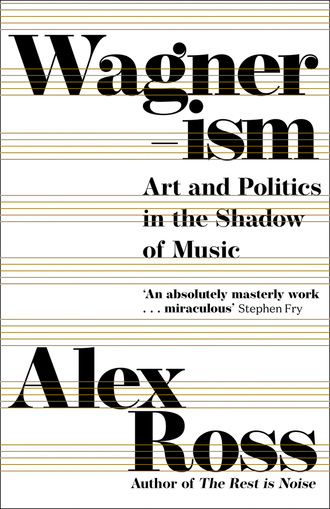

Wagnerism

WAGNERISM

ART AND POLITICS

IN THE

SHADOW OF MUSIC

Alex Ross

Copyright

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.4thEstate.co.uk

This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2020

Copyright © Alex Ross, 2020

Jacket design by Jo Thomson

Alex Ross asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

Grateful acknowledgment is made for permission to reprint the following previously published material:

Ingeborg Bachmann, excerpt from ‘Gently and Softly,’ translated by Peter Filkins, from Darkness Spoken: The Collected Poems of Ingeborg Bachmann. Copyright © 1978, 2000 by Piper Verlag GmbH, München. Translation copyright © 2006 by Peter Filkins. Reprinted with the permission of The Permissions Company, LLC on behalf of Zephyr Press, zephyrpress.org.

Lines from ‘Música rocosa i roja o La força teatral,’ by Joan Brossa, from Carrer de Wagner. By kind permission of the Fundació Joan Brossa.

Lines from ‘The Ring Cycle,’ from Collected Poems, by James Merrill. Copyright © 2001 by the Literary Estate of James Merrill at Washington University. Used by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Lines from ‘Opera’, from Inventions of the March Hare, and The Waste Land, by T.S. Eliot, used by permission of Faber and Faber Ltd.

Owing to limitations of space, illustration credits can be found here

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780007319053

Ebook Edition © August 2020 ISBN: 9780007518517

Version: 2020-08-27

Dedication

In memory of Andrew Patner

Epigraph

Wagner sums up modernity. It can’t be helped, one must first become a Wagnerian.

—FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE

The best in this kind are but shadows;

and the worst are no worse, if imagination amend them.

—A Midsummer Night’s Dream

CONTENTS

COVER

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT

DEDICATION

EPIGRAPH

PRELUDE: Death in Venice

1. RHEINGOLD: Wagner, Nietzsche, and the Ring

2. TRISTAN CHORD: Baudelaire and the Symbolists

3. SWAN KNIGHT: Victorian Britain and Gilded Age America

4. GRAIL TEMPLE: Esoteric, Decadent, and Satanic Wagner

5. HOLY GERMAN ART: The Kaiserreich and Fin-de-Siècle Vienna

6. NIBELHEIM: Jewish and Black Wagner

7. VENUSBERG: Feminist and Gay Wagner

8. BRÜNNHILDE’S ROCK: Willa Cather and the Singer-Novel

9. MAGIC FIRE: Modernism, 1900 to 1914

10. NOTHUNG: The First World War and Hitler’s Youth

11. RING OF POWER: Revolution and Russia

12. FLYING DUTCHMAN: Ulysses, The Waste Land, The Waves

13. SIEGFRIED’S DEATH: Nazi Germany and Thomas Mann

14. RIDE OF THE VALKYRIES: Film from The Birth of a Nation to Apocalypse Now

15. THE WOUND: Wagnerism After 1945

POSTLUDE

CHRONOLOGY OF EVENTS IN WAGNER’S LIFE

PICTURE SECTION

NOTES

INDEX

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ILLUSTRATION CREDITS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ALSO BY ALEX ROSS

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

PRELUDE

DEATH IN VENICE

Only down deep

is it trusty and true:

false and base

is the revelry above!

At the end of Das Rheingold, the first part of Richard Wagner’s operatic cycle The Ring of the Nibelung, the gods are entering the newly built palace of Valhalla and the Rhinemaidens are singing in dismay. The river nymphs know that Valhalla rests on a corrupt foundation, its laborers paid in gold extracted from the water’s depths.

On the evening of February 12, 1883, some three decades after Rheingold was finished and seven years after the Ring was first performed complete, Wagner played the Rhinemaidens’ lament on the piano. As he got into bed, he remarked, “I am fond of them, these subordinate beings of the deep, with their yearning.”

Wagner was sixty-nine years old, and in poor health. Since September 1882, he had been living with his family in a side wing of the Palazzo Vendramin Calergi, on the Grand Canal, in Venice. Sequestered in what he called his “blue grotto”—a chamber decorated in multicolored satin fabrics and white lace—he was writing an article titled “On the Womanly in the Human.” When it was done, he had said, he would begin composing symphonies.

The next day, clad in a pink dressing gown, Wagner continued to work on his essay. In a corner of a blank page, he wrote: “Nonetheless, the process of the emancipation of women goes ahead only amid ecstatic convulsions. Love—tragedy.” Elsewhere in the family suite, Cosima Wagner, the composer’s second wife, was playing Schubert’s song “Lob der Tränen” (“In Praise of Tears”) at the piano, in an arrangement by her father, Franz Liszt.

Sometime after two, Wagner cried out, asking for Cosima and his doctor, Friedrich Keppler. He was found writhing in pain, a hand clutched to his heart. A maid and a valet carried him to a settee, next to a window facing the Grand Canal. When the valet tried to remove the gown, something fell to the floor, and Wagner uttered his apparent last words: “My watch!” At around 3 p.m., Dr. Keppler entered, and established that the Meister, the Sorcerer of Bayreuth, the creator of the Ring, Tristan und Isolde, and Parsifal, the man whom Friedrich Nietzsche described as “a volcanic eruption of the total undivided artistic capacity of nature itself,” whom Thomas Mann called “probably the greatest talent in the entire history of art,” was dead.

By late afternoon, a crowd had gathered at the street entrance of the Palazzo Vendramin. Dr. Keppler came to the door and said, “Richard Wagner died an hour ago, following a heart attack.” Murmurs went up: “Richard Wagner dead, dead.” The news spread through a city drenched in rain: “Riccardo Wagner il famoso tedesco, Riccardo Wagner il gran Maëstro del Vendramin è morto!” John W. Barker’s book Wagner and Venice quotes the first obituary, which ran the next morning in La Venezia:

Deceased yesterday in our city was the musical genius of Germany.

The composer of Lohengrin was for some months among us with his wife and his delightful children, hoping that the mild air of our heaven might have served to restore him in health, delicate for some time …

Last evening we went to the Palazzo Vendramin Calergi to have news.

—Riccardo Wagner is dead—there it was told—and his widow, kneeling before his corpse, crazed with grief, hardly believing that her beloved companion sleeps the eternal repose!

How many memories crowd upon our mind—the bold struggles that he sustained, the sublime victories that he achieved—the art that he created—the bitter enemies he had—the fanatical partisans that idolized him as a God—the crowned kings who knelt down before him!

No more—a corpse!

But from him rises a voice that will not die—and perhaps will become in time more powerful, more hearkened to, more beloved.

Five thousand telegrams were reportedly dispatched from Venice in a twenty-four-hour period. The news traveled as far as Dunedin, New Zealand, where Fergus Hume composed a sonnet hailing Wagner’s “Æschylean music.”

Voluminous obituaries reviewed the composer’s epic life: his middle-class origins; his early struggles in provincial posts; his failed first stab at Parisian fame; his years as a progressive opera director in Dresden; his participation in the revolutions of 1848–49; his Swiss exile; his quarter-century of work, with long interruptions, on the Ring; his disorderly private life, including two marriages and interminable financial crises; his miraculous rescue by King Ludwig II of Bavaria; the building of a festival theater in Bayreuth, Germany; the premiere there of the Ring, in 1876, with two emperors and two kings in attendance; and the mystical farewell of Parsifal, in 1882. “The life of Richard Wagner affords a remarkable illustration of the results of persistent effort in carrying out to its conclusion the inspiration of genius,” the New York Times intoned. The more unsavory aspects of Wagner’s character were usually omitted. The New York Daily Tribune, in an obituary that consumed more than a page of fine newsprint, gave only one sentence to his vicious attacks on Jews.

Radical-minded Wagnerites thought that the mainstream tributes had got it all wrong. The American firebrand Benjamin Tucker wrote in his journal Liberty: “None of the newspapers, in their obituaries of Richard Wagner, the greatest musical composer the world has yet seen, mention the fact that he was an Anarchist. Such, however, is the truth. For a long time he was intimately associated with Michael Bakounine, and imbibed the Russian reformer’s enthusiasm for the destruction of the old order and the creation of the new.” Moncure Conway, a freethinker, abolitionist, and pacifist from the American South, made a similar argument in a memorial sermon in London. Through artists like Wagner, Conway said, “the old order has become unreal.”

Fellow composers, whatever their opinion of the man, were shocked by his departure. “Vagner è morto!!!” wrote Giuseppe Verdi, Wagner’s Italian antipode. “Reading the news yesterday, I was horror-struck, I can tell you! There is no question. It is a great personality that has disappeared! A name that leaves a most powerful imprint on the History of Art!!!” Johannes Brahms, seen as Wagner’s chief German adversary, sent a large laurel wreath to the funeral. Young zealots were in despair. Gustav Mahler ran through the streets in tears, crying, “The Master has died!” Pietro Mascagni secluded himself for several days, writing at high speed the Elegia per orchestra in morte di R. Wagner. Liszt memorialized his son-in-law in a strange piano sketch that wavered between emphatic assertions of major-key tonality and meanderings in harmonic limbo. It was titled R. W.—Venezia. A few months later, Liszt produced a still gloomier, eerier piece called At the Grave of Richard Wagner.

There was a flurry of memorial poems. “He hath ascended in the Magic Car,” wrote the American educator William Henry Venable, in “Wagner Dead.” Algernon Charles Swinburne rose above the rest with an elegy titled “The Death of Richard Wagner,” its alliterations echoing the composer’s bardic manner:

Mourning on earth, as when dark hours descend,

Wide-winged with plagues, from heaven; when hope and mirth

Wane, and no lips rebuke or reprehend

Mourning on earth.

The soul wherein her songs of death and birth,

Darkness and light, were wont to sound and blend,

Now silent, leaves the whole world less in worth.

The thirty-eight-year-old Friedrich Nietzsche was in Rapallo, completing the first part of Thus Spoke Zarathustra, which proclaims the death of all gods and the coming of the Übermensch. Nietzsche later noted that he had finished his task “in that sacred hour in which Richard Wagner died in Venice.” After seeing the newspapers the following day, he spent several days ill in bed, stupefied. Nietzsche’s brother-in-law, Bernhard Förster, heard the news in Asunción, Paraguay, where he was making plans to establish an Aryan colony. “What a thunderbolt it is to hear that Wagner has gone to Nirvana,” Förster wrote to a friend, unaware that the composer had cast doubt on the Paraguay scheme a few days before his death.

Commemorative concerts took place on both sides of the Atlantic. “All the world there,” said Mary Gladstone, William Gladstone’s daughter, of an all-Wagner event at the Crystal Palace, in London. Four days after the composer’s death, the Boston Symphony discarded its scheduled program in favor of a “Wagner Night.” Various institutions in New York City—the New York Academy of Music, the Philharmonic Society, the Brooklyn Philharmonic, and the New York Chorus Society—paid homage. In Paris, the Colonne and Lamoureux orchestras mounted impromptu festivals. The most extravagant tribute was held, fittingly, in Venice, on April 19. Outside the Palazzo Vendramin, the conductor Anton Seidl led an orchestra arrayed in bissone, Venice’s ornate ceremonial boats, with hundreds of people observing from gondolas. Siegfried’s Funeral Music, the orchestral epitaph from Götterdämmerung, resounded on the Grand Canal.

The American essayist Sarah Butler Wister attended one of the Paris memorials, her interest perhaps piqued by her musically inclined son Owen, who later wrote the classic Western novel The Virginian. The following year, in The Atlantic Monthly, Wister gave a vivid account of the occasion, recording not only the adoration of progressive factions but also the hatred of conservative patriots, who had not forgotten Wagner’s chauvinistic agitation during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71:

The music had swallowed us alive, like a gulf. The excitable audience was wrought into a frenzy, in which other passions than melomania had a share. There was in some hearers real antipathy to the composer, in others animosity to him as a German, and these prejudices struggled fiercely against the dominating power of the music and the rapturous enthusiasm of the majority. The grandeur of the Tannhaüser, the charm of the spinning chorus from the Flying Dutchman, the gravity and interest of the prelude to Parsifal, kept the dissidents in check until the wild gallop of the Valkyrie began. The stern daughters of Odin rode on the whirlwind above the din of the battle-field, sweeping mortals with them on their breathless course; and then the storm burst in hisses, hooting, stamping, shrill whistles, calls, cries, and counter-cries: “That’s not music!” “Bravo! bravo! bravissimo!” “If the Germans want to hear it, let them go hear it at home!” “Bis! bis!” (Again, again.) “You sha’n’t have it!” “Superb! Magnificent!” “Stop it!” “Turn out the blackbirds!” (the men with the whistles.) “Down with the circus-riders!”

Memorials in German-speaking lands were impassioned and frequently politicized. In Austria, an attachment to Wagner was common among youthful pan-Germanists—those who advocated the unification of Germanic peoples under one national banner. According to the author Hermann Bahr, young Viennese would declare themselves Wagnerites before they had heard a bar of the music. A friend of Bahr’s once camped out for three days at a train station in the mistaken belief that the Meister was due to arrive.

On March 5, Vienna’s German student association organized a tribute in the Sophiensaal, where the Strausses once held waltz evenings. Several thousand attended. Pan-German rhetoric mounted as the event went on, with antisemitic slurs becoming audible. Bahr, then a member of the Albia fraternity, delivered a fiery oration. At the climax, he employed a metaphor derived from Parsifal, comparing Germany to Wagner’s chaste hero and Austria to the outcast Kundry. The Reich was implored to “have mercy and no longer forget the sorely penitent Kundry, still waiting yearningly on the other side of the border for her Redeemer!” The phrase touched off a commotion, with the students singing “Die Wacht am Rhein” and the Deutschlandlied. The police intervened. Decades later, Bahr remembered Georg von Schönerer, the pro-German, anti-Jewish rabble-rouser, swinging a club and sputtering with anger.

The incident drove one Jewish alumnus of Albia to resign from the society in protest. Expressing his sorrow that a Wagner memorial had “developed into an antisemitic demonstration,” he wrote: “I would not think of polemicizing here against this retrograde fashion of the day; I will mention only in passing that even as a non-Jew I would have condemned, from the standpoint of the love of freedom, this movement to which my fraternity has to all appearances been connected. To all appearances; for if one does not audibly protest against actions of this kind, one is bound in solidarity to them. Qui tacet, consentire videtur! [Silence gives consent!]” This was Theodor Herzl, the future architect of the Zionist state. Herzl, too, felt drawn to Wagner, and the composer’s antisemitism did not discourage him. While he was writing The Jewish State, in Paris in 1895, he often attended performances of Tannhäuser, Wagner’s tale of a wanderer seeking redemption. “Only on the evenings when no opera was performed,” Herzl later recalled, “did I doubt the rightness of my ideas.”

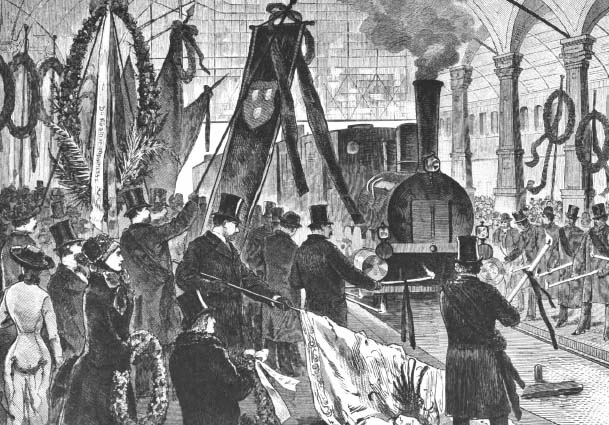

Wagner’s coffin arriving in Munich

As news of Wagner’s death rippled outward, his remains journeyed back to Bayreuth, the Franconian town where he had established his festival and home. The casket was brought by water from the Palazzo Vendramin to the Venice railway station, whence it traveled in a mortuary car across Austria to Germany, arriving in Bayreuth on the evening of February 17. Three additional railway carriages were filled with wreaths. Twenty-seven firemen kept watch at the station overnight. The funeral began at four the following day, with a regimental band playing Siegfried’s Funeral Music. After speeches were delivered, a long procession moved slowly through the city, toward the villa that Wagner had christened Wahnfried—“peace from delusion.” The deceased was placed in a tomb that had been built in the yard behind Wahnfried, next to the grave of a favorite dog, a Newfoundland named Russ.

La Venezia did not exaggerate when it said that Cosima Wagner was “crazed with grief.” Once the guests had departed, the Meisterin, as she would now be known, climbed down into the grave and lay next to the casket. She had ordered her daughters to cut off all her hair, and a velvet cushion containing the shorn locks was placed on the dead man’s breast. She seemed to want to die with him. Eventually, Siegfried, her thirteen-year-old son, persuaded her to return to the house. She would live until 1930, having remade Bayreuth as a cultural monument.

Wagner’s resting place became a site of homage. One sonneteer took note of a “wondering band / Of loitering pilgrims who entrancèd stand.” John Philip Sousa, the American March King, went to some trouble to gain entrance, persuading the Wahnfried housekeeper to let him in when Cosima was away. Often, visitors left with a souvenir. The Boston arts patron Isabella Stewart Gardner took a leaf from the ivy that covered the grave and pressed it into her scrapbook. The composers Anton Bruckner and Emmanuel Chabrier also collected vegetation; Chabrier displayed his Wagner ivy in a box in his office. Rev. H. R. Haweis, the author of the bestselling tract Music and Morals, helped himself to a branch of a fir tree that was hanging overhead. A character in Upton Sinclair’s novel King Midas brings home a pebble.

Some pilgrimages were less sentimental. The African-American writer and activist W. E. B. Du Bois, when attending the festival in 1936, walked past the grave twice a day. Mindful of the composer’s racist legacy, Du Bois could still write, “The musical dramas of Wagner tell of human life as he lived it, and no human being, white or black, can afford not to know them, if he would know life.” When Leonard Bernstein stopped at the site, he joked that the slab was big enough that you could dance on it. Bernstein was undoubtedly thinking not only of Wagner but also of Adolf Hitler, who, on his first visit, in 1923, stood at the grave for a long time, alone.

Wahnfried is now the site of the Richard Wagner Museum. The sofa on which the Meister died—the Sterbesofa—can be seen in an upstairs room. The Palazzo Vendramin is occupied by the Casinò di Venezia, which offers poker, blackjack, and roulette under the slogan “An Infinite Emotion.” Facing the Grand Canal is a commemorative plaque, for which the poet-politician Gabriele d’Annunzio composed a suitably elusive text, in 1910:

In this palace

the souls hear

the final breath of Riccardo Wagner

perpetuated like the tide

which laps the marble stones.

The global ceremonies of mourning in 1883 showed how immense a shadow Wagner cast on the world in which he lived. The truly extraordinary thing is that after his death the shadow grew still larger. The chaotic posthumous cult that came to be known as Wagnerism was by no means a purely or even primarily musical event. It traversed the entire sphere of the arts—poetry, the novel, painting, theater, dance, architecture, film. It also breached the realm of politics: both the Bolsheviks in Russia and the Nazis in Germany used Wagner’s music as a soundtrack for their attempted reengineerings of humanity. The composer came to represent the cultural-political unconscious of modernity—an aesthetic war zone in which the Western world struggled with its raging contradictions, its longings for creation and destruction, its inclinations toward beauty and violence. Wagner was arguably the presiding spirit of the bourgeois century that achieved its highest splendor around 1900 and then went to its doom.