Полная версия

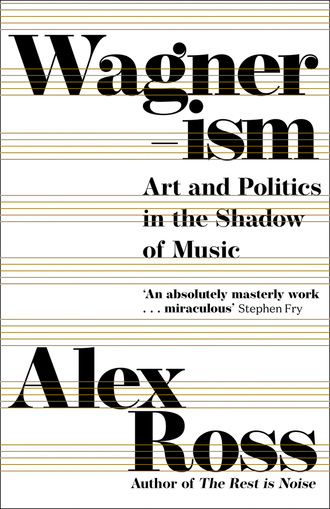

Wagnerism

In 1912, Steiner said, “We have been thinking about a kind of Bayreuth.” A year later, in the Swiss town of Dornach, outside Basel, he laid the foundation stone for a hilltop complex that he called the Goetheanum—a structure defined by two intersecting domes. Some interior features, particularly the stage space underneath the smaller dome, resembled the Grail Temple set in Parsifal. After the building burned, in 1922, the Goetheanum was rebuilt in even more inventive style, its undulating forms prophetic of late twentieth-century architectural trends. Many “new Bayreuths” were imagined in the fin-de-siècle years, but few led to tangible results. Not only did Steiner see his vision through, but his temple still stands, serving as the world headquarters of Anthroposophy. To see it rising above Dornach is like glimpsing the Festspielhaus from the Bayreuth train station: the impossible has become real.

YEATS AND THE CELTIC TWILIGHT

“Westward roams the glance / Eastward strikes the ship,” sings a young seaman at the outset of Tristan. The vessel is bound for King Mark’s castle in Cornwall; Isolde is gazing back toward her native Ireland. An injured Celtic pride is implicit in the heroine’s rage at the outset of the opera (“Who dares to mock me?”). Such touches undoubtedly boosted Wagner’s popularity in Ireland, although he had a following there even before Tristan was widely known. Around the turn of the century, Carl Rosa’s company performed most of Wagner’s operas in Dublin, attracting flocks of writers and artists, including the young James Joyce.

The period of Wagner’s ascendancy coincided with the cresting of Irish nationalism. More than a few artists and impresarios looked to the composer as they pondered how to forge their own political identity. The new Irish state, whatever form it took, would need its native myths, legends, heroes, and leitmotifs. Cultural pride mingled easily with an influx of mystical and esoteric movements. The Celtic Revival concerned itself with old Gaelic literature and age-old Irish folktales, resulting in a heightened awareness of faeries, elves, ghosts, and other supernatural entities. Insofar as Wagner functioned as a conduit for such half-forgotten spirit forces, he became an honorary member of the movement that W. B. Yeats called the Celtic Twilight.

Wagnerism wafted around the Irish Literary Theatre, which Yeats co-founded in 1899. The project received backing from Annie Horniman, an English theater maven who went to Bayreuth almost every year and wished to create an equivalent institution in Ireland. As the literary scholar and biographer Adrian Frazier writes, Yeats was Horniman’s Wagner, and “the theater was to be his Bayreuth.” Horniman also designed costumes for several of the theater’s productions; those for Yeats’s The King’s Threshold are said to have looked like the costumes in Bayreuth’s Tristan.

Edward Martyn and George Moore, two other founders of the theater, were keen Wagnerites who sometimes greeted each other by whistling Siegfried’s motif. Martyn, a wealthy landowner who was active as a musician and a dramatist, valued the composer’s “cult of liturgical aestheticism.” In his 1899 play The Heather Field, a deranged landlord has visions of nymphs and faeries, of stories of the Rhine, of a rainbow, of “strange solemn harmonies” of singing boys. Unexpectedly, this Gaelic-Gothic spirit later became the first president of Sinn Féin, which led the drive toward Irish independence in 1921.

Moore, a cousin of Martyn’s, spent much of his youth in Paris, where he consorted with Dujardin and Mallarmé. Accompanying Martyn on expeditions to Bayreuth, the musically untrained Moore felt that there was “something in [Wagner’s] art for everybody, something in his music for me.” Moore’s 1898 novel Evelyn Innes is an early entry in the small but lively genre of Wagner-soprano fiction, which Willa Cather brought to its zenith. Under the influence of a Wagnerite named Owen Asher, Evelyn pursues an operatic career and achieves great success, winning the approval even of Cosima Wagner—though the Meisterin deems her Brünnhilde too womanly and insufficiently godlike. Evelyn also meets an austere young composer named Ulick Dean, who resists the Wagner craze but is gripped with desire for Evelyn on hearing her sing Isolde. Afterward, “she threw herself upon him, and kissed him as if she would annihilate destiny on his lips.” As in Péladan, Tristan acts as an aphrodisiac.

Evelyn Innes has potboiler elements, but it also experiments with interior monologue in the Dujardin mode. Evelyn’s love life and stage career come into conflict with longings for a pious existence. She mulls over her predicament in bed, ellipses indicating pauses in her thoughts. “It was unendurable to have to tell lies all day long—yes, all day long—of one sort or another. She ought to send them both away … But could she remain on the stage without a lover? Could she go to Bayreuth by herself? Could she give up the stage? And then?” She indeed walks away, forgoing the chance to sing Kundry in Bayreuth, and enters a convent, where she carries on singing Wagner all the same. Unusually, the sensual-spiritual division of Tannhäuser becomes the concern of a female rather than a male protagonist. For Evelyn, singing Wagner is merely a stage of a larger quest, one that dominates the novel’s sequel, Sister Teresa.

Ulick Dean’s physical appearance is modeled on that of Yeats. Moore writes: “He had one of those long Irish faces, all in a straight line, with flat, slightly hollow cheeks, and a long chin. It was clean shaven, and a heavy lock of black hair was always falling over his eyes. It was his eyes that gave its sombre ecstatic character to his face. They were large, dark, deeply set, singularly shaped, and they seemed to smoulder like fires in caves, leaping and sinking out of the darkness.” Certain of Ulick’s views sound like Yeats’s, as when he says that the Celtic gods are alive for him, or when he extols William Blake. Ulick’s operas adapt Irish tales, like Connla and the Fairy Maiden, and Diarmuid and Gráinne. His style is full of “strange, old-world rhythms, recalling in a way the Gregorian she used to read in childhood in the missals, yet modulated as unintermittently as Wagner.” And Ulick surely speaks for Yeats when he says, in parting from Evelyn, “God is our quest—you seek him in dogma, I in art.”

Yeats’s language sings across the page, but his knowledge of music was limited. Moore bluntly called him “unmusical.” That lack did not prevent him from citing Wagner and imitating his methods. The cultures in which Yeats moved—the Celtic Revival, London Aestheticism, Parisian Symbolism, Theosophy and its variants—were all sufficiently soaked in Wagner that he could absorb the influence without having tasted it firsthand. After 1902, Yeats also delved into Nietzsche, whose posthumous vogue was well under way. The dispute between the Germanic titans concerned the poet little: both were models of aesthetic imperiousness and heroic force.

For Yeats, as for many others, Wagner showed how folk sources could shape a national consciousness. In his 1898 essay “The Celtic Element in Literature,” he wrote of Ireland’s connection to the “ancient religion of the world, the ancient worship of Nature.” The Celts, he said, were “nearer to ancient chaos.” The Scandinavian tradition drew from similar sources. Through the medium of Wagner, the Nordic sagas had become “the most passionate element in the arts of the modern world.” Yeats also considered the composer an agent of Symbolism, “the only movement that is saying new things.” Like Villiers de l’Isle-Adam, Mallarmé, the Pre-Raphaelites, and Maeterlinck, Wagner had found spiritual intensity in the practice of his art, fighting against materialism and rationalism. In another article, Yeats placed the “ecstasy of Parsifal” alongside William Morris’s The Well at the World’s End and Villiers’s Axël in the category of art that seeks to “bring again the golden age.”

Yeats’s occult adventures led him first to Theosophy’s Esoteric Section and then to the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, which had been co-founded in 1888 by MacGregor Mathers, a charismatic English guru of invented Scots heritage. More insular than Theosophy, the Golden Dawn burrowed into Rosicrucian, Masonic, and Egyptian ritual. In the usual fashion, it underwent schisms and quarrels. Mathers placed his hopes in Aleister Crowley, who progressed from the Golden Dawn to Thelema, a discipline of his own invention. Crowley’s Holy Books make heavy use of Wagner: the Book of Thoth includes a phallic interpretation of Parsifal, saying that the hero “attains to puberty” when he grasps the Holy Spear. Crowley also wrote a Tannhäuser play in which Venus is revealed as Lilith—“The soul of the Obscene / Incarnate in the spirit.”

Although Yeats never ventured quite so far afield, his occult activities were a heady brew of poetic ambition, political fantasy, and sexual desire. For many years, the chief object of his romantic longing was the Irish nationalist activist Maud Gonne, another member of the Golden Dawn. A devout Wagnerian, Gonne probably did more than anyone to stir Yeats’s interest in the composer, having once told him that Parsifal is “worth travelling round the whole world to hear.” She was often likened to a Valkyrie, and invited the comparison by wearing a hat adorned with black wings. Her first trip to Bayreuth was in 1886, when she was nineteen. Soon after, she fell in love with Lucien Millevoye, a right-wing French politician who shared her Wagnermania. Gonne bore a child out of wedlock, who died young. In a turn of events that could have been scripted by Péladan, she came to believe that the boy could be reincarnated if another child were conceived in the vicinity of the corpse. Supposedly, she and Millevoye proceeded to make love at the tomb. Their second child was named, of course, Iseult.

Thanks to informants like Gonne, Moore, and Horniman, Yeats could speak confidently about Bayreuth’s sightlines and unified stage picture. He also expertly deployed Wagnerite rhetoric. In 1898, he got into a public debate with the critic John Eglinton on the question of the Irish literary revival. Eglinton rejected the idea of an Irish national literature founded on ancient legend, contending that the latter had no relevance for the modern age. In response, Yeats brought up Ibsen’s Peer Gynt and the Wagner dramas, which “are becoming to Germany what the Greek Tragedies were to Greece.” Eglinton replied, in turn, that Bayreuth did not strike him as a plausible rebirth of Athenian democracy. Yeats shot back that Wagner’s impact was hardly limited to the tony crowd at Bayreuth: it stretched across Europe and fired the imaginations of contemporary writers such as Villiers.

The Irish Literary Theatre opened in 1899 with Yeats’s The Countess Cathleen—a tale of a munificent aristocrat who sacrifices her soul to save her land from famine and demons. The lead character, intended for Gonne, resembles nobly self-obliterating Wagnerian heroines like Senta in The Flying Dutchman, Elisabeth in Tannhäuser, and Brünnhilde. The premiere production, static and hieratic in style, apparently took inspiration from Bayreuth. The stage directions suggest some mixture of the Ring and Parsifal: “The darkness is broken by a visionary light. The Peasants seem to be kneeling upon the rocky slope of a mountain, and vapour full of storm and ever-changing light is sweeping above them and behind them … A sound of far-off horns seems to come from the heart of the light.” Tristan lurks behind Yeats’s Diarmuid and Grania, co-written with Moore between 1899 and 1901, and his Deirdre, from 1907. Both plays involve a triangle of two younger lovers and an older man of authority.

Yeats’s most consciously Wagnerian work is The Shadowy Waters, a short play first conceived when he was a teenager, written and rewritten between 1894 and 1900, and then revised again at intervals in the following decade. In the tradition of Tristan and Axël, it tells of a pair of doomed lovers, named Forgael and Dectora. The setting is vague, but Yeats specified in one draft that the actors should be “dressed like Wagner’s personages, except that the men do not wear winged helmets.” The action begins, as in Tristan, on the deck of a ship, with the voice of a sailor. Forgael, the sailors’ leader, is a mariner-musician on an obscure quest—a cross between Tristan and the Flying Dutchman, the wanderer in search of redemptive love. Dectora enters as a captured queen, very Isolde-like, but Forgael’s magic harp makes her lose interest in the world.

During an American trip in 1903 and 1904, Yeats saw the Met’s staging of Parsifal, and, as he later recounted, objected to its literalism. “Parsifal symbolises an action that takes place in the mind alone,” he remembers telling the Met director. He wanted a more suggestive, dimly lit production for The Shadowy Waters, in Parisian Symbolist style. The 1904 premiere in Dublin went badly, but the play found a more receptive public when the Theosophical Society hosted a performance at its congress in London in 1905. Such eminences as Maeterlinck, Annie Besant, and Rudolf Steiner attended the meeting, and all may have seen The Shadowy Waters. Even in that rarefied milieu, though, Yeats was criticized for his lack of dramatic action. He subjected the play to a heavy revision, shedding “needless symbols.” After reading Arthur Symons’s essay “The Ideas of Richard Wagner,” Yeats wrote to the author: “The Wagnerian essay touches my own theories at several points, and enlarges them at one or two.” While struggling with one passage, Yeats came upon “that paragraph where Wagner insists that a play must not appeal to the intelligence, but … directly to the emotions.”

As Yeats entered his maturity, the play took on a harder edge, losing its Celtic Twilight glow. Even so, the debt to Wagner becomes, if anything, more pronounced. In the revised text published in 1906, the sailor’s first line is “Has he not led us into these waste seas / For long enough?” This echoes a phrase in Tristan that will also be quoted in T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land: “Waste and empty the sea.” When the lovers meet, they preach to each other a world-liquidating love, looking toward a “country at the end of the world” that seems coterminous with Tristan’s “Wunderreich der Nacht,” the wonder-realm of night:

I would that there was nothing in the world

But my beloved—that night and day had perished,

And all that is and all that is to be,

All that is not the meeting of our lips.

It is also a mystical transport to a place beyond the material world, a plane of initiation where eternal knowledge is attained:

Where the world ends

The mind is made unchanging, for it finds

Miracle, ecstasy, the impossible hope,

The flagstone under all, the fire of fires,

The roots of the world.

This imagery recurs in Yeats’s 1930 poem “Byzantium”: “At midnight on the Emperor’s pavement flit / Flames that no faggot feeds, nor steel has lit, / Nor storm disturbs, flames begotten of flame …”

In the mid-twenties, on a visit to Palermo, Yeats stayed at the Grand Hotel et des Palmes, where, four decades earlier, Wagner had finished Parsifal and sat for a portrait by Renoir. One could see the room in which he stayed and, purportedly, a pen with which he wrote. Visiting Palermo’s Cappella Palatina, with its Byzantine mosaics, Yeats heard a local story to the effect that the chapel had given rise to the Grail Temple in Parsifal. That claim is biographically doubtful—Wagner mentioned Siena Cathedral as his principal scenic source—yet Yeats seized on it. The path that leads to Monsalvat points onward to the dream city of Byzantium, where broken lives are gathered into the artifice of eternity.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.