Полная версия

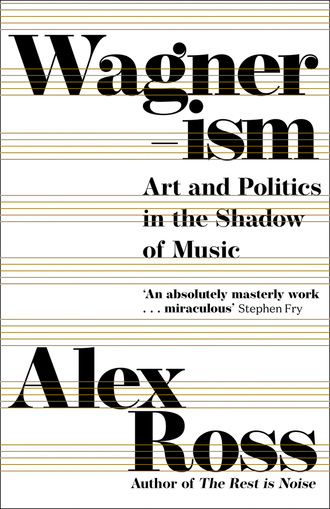

Wagnerism

Yet the Übermensch is something other than a fearless, boyish hero. (Nietzsche’s misogyny makes a female Übermensch unlikely.) In fact, he eludes any kind of brief description. His mastery is rooted in tremendous struggle, not only with the outer world but with himself. Nietzsche melts down the materials of the Ring as he forges his own creation.

In the last book of Zarathustra, the protagonist meets the Zauberer, the Sorcerer, one of several tempters who try to lure him from his path. Even if we hadn’t read Nietzsche’s prior references to the “old sorcerer,” we would recognize Wagner’s personality in this restless, twitching, frantically gesturing figure, who babbles self-pitying monologues and dubs himself “the greatest person living today.” Zarathustra exposes him as an actor, a counterfeiter. After spluttering in protest, the Sorcerer gives in: “I am weary of and nauseated by my arts, I am not great, why do I pretend!” A conciliatory dialogue follows, and the Sorcerer hails Zarathustra as “a vessel of wisdom, a saint of knowledge, a great human being.” This seems pure fantasy on Nietzsche’s part, an imaginary victory over his mentor turned oppressor—although he claims in his notebooks that when he confronted Wagner in private the composer accepted the criticism. “I wish that he would also do it publicly. For what constitutes the greatness of a character other than that he is capable, for the sake of truth, of also taking sides against himself?”

The Sorcerer later stages a momentary comeback. In a pseudo-Christian supper scene, he strums his harp and sings mumbo-jumbo redolent of the Tristan libretto. The assembled company is hypnotized. Before long, all turn religious, kneeling before an ass and chanting Parsifalian pieties. Zarathustra responds with a string of contemptuous rebuttals, leading to another make-believe dialogue with Wagner’s ghost:

“And you,” said Zarathustra, “you wicked old sorcerer, what have you done! Who in these liberated times is supposed to believe in you anymore, if you believe in such asinine divinities?

“What you did was a stupidity; how could you, you clever one, commit such a stupidity!”

“Oh Zarathustra,” replied the clever Sorcerer, “you’re right, it was a stupidity—and it’s been hard enough for me.”

The pious mood gives way to roguish laughter, and it is in this spirit that the book ends: learning to laugh, to love the earth, to love what is fated, to be willing, under the doctrine of eternal recurrence, to relive the same life in every excruciating detail.

BECOMING WAGNER

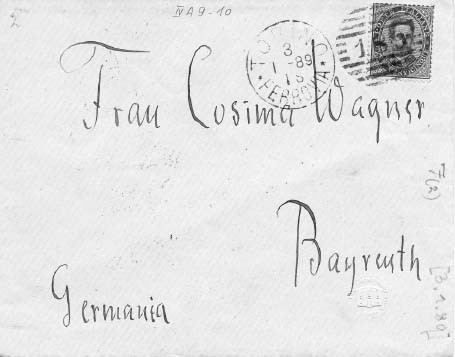

Nietzsche writes to Cosima Wagner, January 1889

On February 3, 1883, Wagner glanced at an article about The Joyful Science, and, according to Cosima, responded with “utter disgust.” He died ten days later. It was not the ending that Nietzsche had pictured for a friendship that remained active in his mind. He was distraught but also relieved. The tension with Wagner had become unbearable. He wrote to Köselitz: “In the end, it was the aged Wagner against whom I had to defend myself; as far as the real Wagner is concerned, I intend in good measure to become his heir.”

In the major works of his last years of sanity, from 1885 to the end of 1888, Nietzsche brings his diatribe against conventional morality to its highest pitch. Beyond Good and Evil provisionally endorses “harshness, violence, slavery, danger in the streets and in the heart, concealment, stoicism, the art of seduction, and devilry of every kind … everything evil, horrible, tyrannical, predatory, and snakelike in humanity.” All this “serves to elevate the species ‘humanity’ as well as its opposite.” On the Genealogy of Morality relates the good and noble to the innocent conscience of the predator, the “magnificent blond beast roaming about lustily after prey and victory.” Modern European civilization, meek and effeminate, has lost touch with the voluptuous cruelty once exhibited by Germanic tribes. The Antichrist continues the theme: “What is good? Everything that heightens in man the feeling of power, the will to power, power itself.” What is bad? Weakness, tolerance, forgiveness, compassion—Mitleid again.

Nietzsche is still looking for a savior figure, an unfettered Siegfried. In the Genealogy, he dreams of a future hero of “sublime malice,” a “redeeming man of great love and contempt.” Insinuating italics differentiate this redeemer from the ascetic hero of Parsifal. Redemption will entail not a flight from reality but a close embrace of the true nature of humanity. Nietzsche’s latter-day defenders posit that he is not actively praising war, aggression, and the rest. Rather, he is acknowledging that human beings will invariably be vicious to one another and to the world around them. Nietzsche’s critique of morality posits that moral language is not the same as moral action, and, indeed, that moral language can serve as a cover for actions that are immoral in the extreme. We must accept the reality of human nature and the vicissitudes of fate. The Dionysian urge is a “triumphal yes to life over and above all death and change.”

The Case of Wagner, written in the spring of 1888, promises to be the ultimate act of apostasy. In a style of high intellectual comedy, Nietzsche pillories German gigantism (“the lie of the grand style”); diagnoses the composer as a pan-European neurosis (“Wagner est une névrose”); coins deft one-sentence summaries of the operas (“You should never be too sure who you are really married to” is Lohengrin); praises Bizet’s Carmen at Wagner’s expense (“Music must be mediterraneanized”); and inserts a cackling footnote to the effect that the author of “Jewishness in Music” might himself have been Jewish. Yet the entire exercise is undercut by a preface that places Wagner at the very heart of modern life. The “case” is especially indispensable to the philosopher, for

where would he find a more knowledgeable guide to the labyrinth of the modern soul, a more articulate connoisseur of souls, than Wagner? Modernity speaks its most intimate language in Wagner: it hides neither its good nor its evil, it has forgotten any sense of shame. And conversely: when one is clear about the good and evil in Wagner, one is close to a reckoning of the value of the modern.—I understand perfectly when a musician says today: “I hate Wagner, but I cannot stand any other music.” But I would also understand if a philosopher were to declare: “Wagner sums up modernity. It can’t be helped, one must first become a Wagnerian …”

What does Nietzsche mean by “modernity”? Competing definitions of the word exist in different intellectual spheres. In philosophy, it is often associated with the formation of a free, self-determined consciousness in the Renaissance and Enlightenment eras. In sociology, it applies more often to nineteenth-century modernization—the economic and social upheaval analyzed by Marx, Weber, and Émile Durkheim. In cultural criticism, the “modern” denotes a radicalization of the arts, culminating in the modernist movements of the early twentieth century. Nietzsche defines modernity more narrowly, as the culture of decadence—overripe, indecisive, weak, detached from primal instincts, premised on false ideas of freedom. He must have known, however, that such an untethered abstraction would strike his readers in various ways. Broader understandings of modernity crowd into our minds. The Case of Wagner is more the opening of a case than the settling of one: it provokes a debate about what it means to be “modern” just as the word is coming into vogue.

Toward the end of his career, Nietzsche drops the pretense of being anti-Wagnerian and confesses his vestigial adoration. In Ecce Homo, a paragraph on Tristan lapses back into the rhapsodic mode of The Birth of Tragedy and “Richard Wagner in Bayreuth”:

To this day I am still searching for a work of such dangerous fascination, of such shuddering sweet infinity, as Tristan—I am searching all the arts in vain … I think that I know better than anyone what tremendous things Wagner was capable of, the fifty worlds of foreign ecstasies that only he had wings to reach; and being what I am, strong enough to turn what is most questionable and dangerous to my advantage and thus become even stronger, I name Wagner the greatest benefactor of my life. That which relates us—the fact that we have suffered more deeply, also from each other, than people of this century are capable of suffering—will reunite our names eternally …

Such passages support Thomas Mann’s belief that Nietzsche’s polemic against Wagner is really a “panegyric with the sign reversed, another form of glorification,” serving more to “goad one’s enthusiasm than to cripple it.”

Most of Nietzsche’s public commentary on Wagner takes the form of propaganda, positive or negative. In the more considered passages of his writings and notebooks, he finds his way to a clear-eyed, nuanced understanding. The Joyful Science dismantles clichés about Wagnerian hugeness and loudness, even before such clichés had fully taken hold. The composer may think of himself as a maker of “great walls and brazen murals,” but he is really a master of psychological moments, an “Orpheus of all secret misery.” The Case of Wagner scorns the cycle’s popular showpieces as so much “noise about nothing.” Instead, we should marvel at the “wealth of colors, of half shadows, of the secrets of dying light … glances, tendernesses, and comforting words.” Wagner is “our greatest miniaturist in music, who can urge an infinity of meaning and sweetness into the smallest spaces.”

Nietzsche also works to rescue Wagner from the triumphalism of the new Reich. In his 1878 notebooks, he sees the Bayreuth ritual as both a self-aggrandizement and a self-enslavement on the part of the German public. The resulting psychological contradiction could lead, he speculates, to a scapegoating of outsiders, such as Jews. One project of the later writings is to separate Wagner from bad national mythologies and guide him toward the Nietzschean ideal of the “good European,” who has no fatherland or motherland. The Teutonic culture-hero venerated in imperial Germany is a “phantom,” unrelated to the immoralist-atheist whom Nietzsche knew in private. The true Wagner is a “foreign country,” a “living protest against all ‘German virtues.’” Nietzsche’s joke about Wagner being translated into German makes the same point. The composer’s unforgivable mistake was that he “condescended to the Germans—that he became reichsdeutsch.”

Most impressively, Nietzsche exposes the neurosis that his own excessive fandom has generated—a dynamic that is by no means unique to Wagnerism. “Wholesale love for Wagner’s art is precisely as unjust as wholesale rejection,” he writes in 1878. “I revenged myself on Wagner for my deceived expectations,” he says. Tellingly, in the midst of such musings, he quotes the passage from Siegfried that Wagner was composing when the two men met in Tribschen: “He who woke me has wounded me!” Nietzsche would appear to be Brünnhilde, sleeping within the ring of fire until the arrogant, flawed hero makes his entrance.

This furiously conflicted relationship is best understood in terms of the Greek agon—the contest between worthy adversaries, in athletics or the arts. Nietzsche wrote about the agon in his 1872 essay “Homer’s Contest,” saying that the Greeks abhorred the predominance of a single figure and desired, “as a means of protection against genius—a second genius.” It is not far-fetched to guess that Nietzsche was thinking of himself and Wagner. As the philosopher Christa Davis Acampora emphasizes, the aim of the agon is not the destruction of the other but the elevation of the self, through a sublimation of the ineradicable human instinct toward aggression and violence. “Richard Wagner in Bayreuth” shows that the composer’s battles with contemporaries were the crucible in which he “became what he is”—an early version of a favorite formula. Likewise, Nietzsche’s agon with Wagner is part of a process of self-formation. In fact, this contest benefits both participants, defining the one and redefining the other. The ritual of going up against Wagner, the dialectic of love and hate, often recurs in the annals of Wagnerism.

Around Christmastime 1888, while staying in Turin, Nietzsche sent a copy of Ecce Homo to Cosima. A draft for the accompanying letter is addressed to “the only woman I have ever revered,” and is signed “The Antichrist.” In the first days of the new year, Nietzsche broke down in the streets of Turin, allegedly after seeing a horse beaten by a coachman. For a few days, he continued to send incoherently stylish correspondence, calling himself “the Crucified” and “Dionysus.” Cosima received several more letters; one of them, addressed to “Princess Ariadne,” announced that the writer’s previous incarnations were Buddha, Dionysus, Alexander, Caesar, Voltaire, Napoleon, and “perhaps also Richard Wagner.” Once he was institutionalized, Nietzsche was heard to say, “My wife, Cosima Wagner, brought me here.”

Having become himself in the course of his agon with Wagner, Nietzsche fell back under the sorcerer’s spell in the end. He lived eleven more years, increasingly blank-eyed, gentle during the day, given to animal groans at night. In fulfillment of his prior prophecies, his work enjoyed an ever-growing vogue, soon to rival Wagnerism in breadth and intensity. But the news of his victory passed him by. In 1900, he was buried by the side of his father’s church.

GÖTTERDÄMMERUNG

On November 21, 1874, Wagner finished the orchestration of Götterdämmerung, ending a project that he had begun twenty-six years earlier. “Thrice sacred, memorable day!” Cosima wrote in her diary. At lunchtime, though, she inadvertently enraged her husband by showing him a letter from her father. Why the letter caused offense is not clear—it seems that Wagner simply found it distracting—but Cosima spiraled into self-castigating despair. “The fact that I dedicated my life in suffering to this work has not earned me the right to celebrate its completion in joy,” she wrote. The two were later reconciled, but the dispute was a strange way to mark the realization of a work that affirms the triumph of world-changing love.

George Bernard Shaw accuses Wagner of a sort of backsliding in Götterdämmerung—of reverting to such grand-opera clichés as “a magnificent love duet … the opera chorus in full parade on the stage … theatrical grandiosities that recall Meyerbeer and Verdi … romantic death song for the tenor.” Shaw neglects the dramatic purpose of such well-worn devices: we have left the realm of the gods and are down on the human plain. Hagen, son of Alberich, is hatching a scheme to defeat Siegfried and win back the Ring. His unwitting ally is his half brother Gunther, the status-seeking chief of the Gibichungs. When Siegfried arrives at the Gibichung court, he is served a memory-erasing potion, so that he forgets Brünnhilde and falls in love with Gunther’s sister, Gutrune. It is decided that Gunther should marry the Valkyrie and that Siegfried should disguise himself as Gunther in order to win her hand. This fully operatic web of deceit stirs resentment and vengefulness on all sides. An infuriated Brünnhilde tells Hagen of Siegfried’s vulnerability—his unprotected back—and Hagen makes fatal use of the information by the waters of the Rhine. Before Siegfried meets his fate, the Rhinemaidens plead one last time for the Ring, their cry of “Weialala leia” grown forlorn.

Siegfried dies, the Funeral Music thunders, and Brünnhilde arrives to deliver her final monologue. “All things, all things, all things I know,” she sings, without entirely disclosing what she has learned. Deciding on the right ending gave Wagner considerable trouble. The essential action was fixed early on: Siegfried’s funeral pyre blazes; Brünnhilde rides her horse, Grane, into the flames; the Ring falls back into the Rhine. But what conclusion should Brünnhilde draw? In the initial 1848 sketch, with its happy message of liberation for all, she exudes revolutionary fervor: “Rejoice, Grane: soon we will be free!” Soon, though, Wagner’s vision darkened. The flames of the pyre consume Valhalla, and the end becomes a Todeserlösung, a redemption through death. In the version that was printed in 1853, he added a passage influenced by Feuerbach, in which material society is overcome by the power of love:

Though the race of gods

passed away like a breath,

though I leave behind me

a world without rulers,

I now bequeath to that world

the hoard of my most sacred wisdom.—

Not goods, not gold,

nor godly glory;

not house, not court,

nor lordly pomp;

not the treacherous bonds

of murky treaties

not the harsh decree

of dissembling convention:

blessed in joy and sorrow—

love alone can be.

The “Feuerbach ending,” as it is known, gave way to a “Schopenhauer ending,” in which Brünnhilde takes cover in visionary solitude:

I draw away from desire’s realm,

I flee forever the realm of delusion;

the open gates

of eternal becoming

I shut behind me …

Deepest suffering

of sorrowing love

opened my eyes:

I saw the world end.

This, too, was excised, to the regret of the young Nietzsche. Ultimately, Wagner chose not to delay the denouement with philosophical musings. Brünnhilde proceeds directly to her final lines, in which she urges Grane toward the flames—“Does the laughing fire lure you to him?”—and jubilantly salutes her beloved: “Siegfried! Siegfried! See! In bliss your wife bids you welcome!”

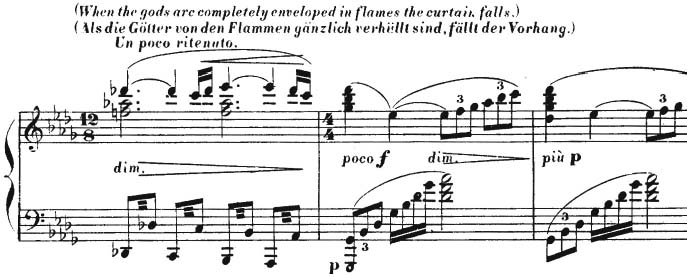

In the orchestra, we hear a reprise of the galloping motif of “The Ride of the Valkyries”—one of the first inspirations that Wagner had for the Ring, in the summer of 1850. It is joined to a regal theme that has been heard only once before in the cycle. In Act III of Walküre, after Brünnhilde saves Sieglinde and the unborn Siegfried from Wotan’s wrath, Sieglinde responds with a hymn of praise, addressing the Valkyrie as “O hehrstes Wunder! Herrliche Maid!” (“O noblest wonder! Glorious woman!”). The melody for these words turns floridly around the tonic note, as in a bel canto aria, and then dips down a seventh before climbing back up to the tonic. Wagner called it the “glorification of Brünnhilde,” although it seems more a glorification of Sieglinde’s selfless love. Once Valhalla falls, this theme becomes sovereign, with a stepwise bass line supplying hymnal gravity. The harmonization is almost sentimental: two-chord sequences like Amens, a wistful turn to the subdominant minor. The cycle ends in an incandescence of D-flat major.

Later it became fashionable to regard the ending of Götterdämmerung as a disappointment. Shaw said it was “trumpery.” Nietzsche thought that Wagner should have stuck with his original ending, in which Brünnhilde “was to say goodbye with a song in honor of free love, leaving the world to the hope of a socialist utopia where ‘all will be well.’” Theodor W. Adorno, one of the leading Wagner skeptics of the twentieth century, compared the closing theme to the finale of Gounod’s Faust, “in which Gretchen hovers as a Christ-angel above the rooftops of a medium-sized German town.”

Many modern Wagnerites are inclined to read the ending not as a turnabout but as a continuation of the composer’s long struggle with political and personal power. In Treacherous Bonds and Laughing Fire—a title derived from the various versions of Brünnhilde’s monologue—Mark Berry asserts that the closing theme is no cliché of Love Triumphing over All but a “shift, albeit partial, from erotic to charitable love,” positing the basis for a humane political state. Slavoj Žižek, similarly, understands it as “a gesture of supreme freedom and autonomy,” the “transformation from eros to agape.” Alain Badiou sees not merely the death of the gods but “the destruction of all mythologies.”

The final tableau of Götterdämmerung includes a silent human chorus, which gathers as the fires consume Valhalla. “Men and women watch with the greatest emotion,” Wagner writes in the full score. In Patrice Chéreau’s epochal 1976–80 production of the Ring at Bayreuth, these citizens of an unknown future turn around as Brünnhilde’s melody is unfurled and move to the front of the stage, looking out at the auditorium. They seem to say, in the words of the musicologist Jean-Jacques Nattiez, “It is up to you!” Their implicit message recalls Wagner’s early prospectus for a festival at which the theater was to have been torn down and the score burnt: “To those who had enjoyed the thing I would then say: ‘Now go do the same!’” The most monumental artwork of the nineteenth century is merely a prelude to future creation. The audience must write the rest.

2

TRISTAN CHORD

Baudelaire and the Symbolists

The Lohengrin riot of 1887

In January and February of 1860, Wagner conducted three concerts of his music in Paris, hoping to conquer a city that had largely shunned him in his youth. He had set his sights on a staging of Tristan und Isolde, his latest and boldest creation. To that end, he included the prelude to Tristan on his programs, alongside selections from The Flying Dutchman, Tannhäuser, and Lohengrin. Concert performances of the prelude had already taken place in Prague and Leipzig, but the Paris of the Second Empire, crowded as it was with republicans, anarchists, bohemians, and the literary vanguard, promised the ideal audience. In the throng at the Théâtre-Italien was Charles Baudelaire, the dark prince of French poetry, who had won infamy three years earlier with the publication of Les Fleurs du mal. “The Death of Lovers,” from that collection, already has the air of Tristan: “Vying to spend their last heat, / Our two hearts will be two vast torches, / Reflecting their double light / In the twin mirrors of our souls.”

To prepare his listeners, Wagner wrote a program note in which he laid out the rudiments of the story. Tristan, the nephew of King Mark of Cornwall, is sailing from Ireland with Princess Isolde, who has been betrothed to Mark as part of a political bargain. Isolde is enraged, because this same Tristan killed her fiancé in battle. During the voyage, she asks Brangäne, her attendant, to prepare a death potion, which she and Tristan will drink together. Brangäne, unwilling to part with her mistress, serves a love potion instead. The prelude gives a preview of the music that accompanies the drinking of the philter, but it stands as an independent orchestral statement, in which we hear

insatiable longing well up from the shyest confession of the tenderest attraction, through anxious sighs, hopes and hesitations, laments and wishes, raptures and torments, to the mightiest onrush, the most violent effort, to find the breach that shows the infinitely yearning heart the way into the sea of endless loving rapture. In vain! Powerless, the heart sinks back to languish in longing, in longing without attainment, since each attainment leads only to renewed desire, until in final exhaustion the breaking glance catches a glimpse of the attainment of the highest rapture: it is the rapture of dying, of ceasing to be, of the final deliverance into that wondrous realm from which we stray farthest when we try to penetrate it with the stormiest force. Do we call it death? Or is it the nocturnal wonder-world, out of which, the legend tells us, an ivy and a vine once grew in intimate embrace over the grave of Tristan and Isolde?