полная версия

полная версияThe American Revolution

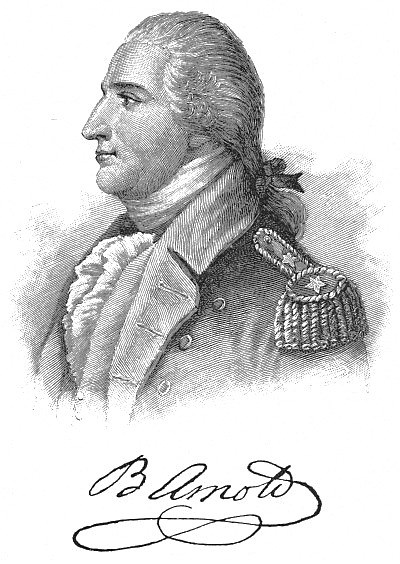

The charge of favouring the Tories may find its explanation in a circumstance which possibly throws a side-light upon his lavish use of money. Miss Margaret Shippen, daughter of a gentleman of moderate Tory sympathies, who some years afterward became chief justice of Pennsylvania, was at that time the reigning belle of Philadelphia; and no sooner had the new commandant arrived at his post than he was taken captive by her piquant face and charming manner. The lady was scarcely twenty years old, while Arnold was a widower of thirty-five, with three sons; but his handsome face, his gallant bearing, and his splendid career outweighed these disadvantages, and in the autumn of 1778 he was betrothed to Miss Shippen, and thus entered into close relations with a prominent Tory family. In the moderate section of the Tory party, to which the Shippens belonged, there were many people who, while strongly opposed to the Declaration of Independence, would nevertheless have deemed it dishonourable to lend active aid to the enemy.

Views of the moderate ToriesIn 1778, such people thought that Congress did wrong in making an alliance with France instead of accepting the liberal proposals of Lord North. The Declaration of Independence, they argued, would never have been made had it been supposed that the constitutional liberties of the American people could any otherwise be securely protected. Even Samuel Adams admitted this. In the war which had been undertaken in defence of these liberties, the affair of Saratoga had driven the British government to pledge itself to concede them once and forever. Then why not be magnanimous in the hour of triumph? Why not consider the victory of Saratoga as final, instead of subjecting the resources of the country to a terrible strain in the doubtful attempt to secure a result which, only three years before, even Washington himself had regarded as undesirable? Was it not unwise and unpatriotic to reject the overtures of our kinsmen, and cast in our lot with that Catholic and despotic power which had ever been our deadliest foe?

OLD LONDON COFFEE HOUSE, PHILADELPHIA

Arnold’s drift toward Toryism

Such were the arguments to which Arnold must have listened again and again, during the summer and autumn of 1778. How far he may have been predisposed toward such views it would be impossible to say. He always declared himself disgusted with the French alliance,[32] and in this there is nothing improbable. But that, under the circumstances, he should gradually have drifted into the Tory position was, in a man of his temperament, almost inevitable. His nature was warm, impulsive, and easily impressible, while he was deficient in breadth of intelligence in rigorous moral conviction; and his opinions on public matters took their hue largely from his personal feelings. It was not surprising that such a man, in giving splendid entertainments, should invite to them the Tory friends of the lady whose favour he was courting. His course excited the wrath of the Whigs. General Reed wrote indignantly to General Greene that Arnold had actually given a party at which “not only common Tory ladies, but the wives and daughters of persons proscribed by the state, and now with the enemy at New York,” were present in considerable numbers. When twitted with such things, Arnold used to reply that it was the part of a true soldier to fight his enemies in the open field, but not to proscribe or persecute their wives and daughters in private life. But such an explanation naturally satisfied no one. His quarrels with the Executive Council, sharpened by such incidents as these, grew more and more violent, until when, in December, his most active enemy, Joseph Reed, became president of the Council, he suddenly made up his mind to resign his post and leave the army altogether.

He makes up his mind to leave the armyHe would quit the turmoil of public affairs, obtain a grant of land in western New York, settle it with his old soldiers, with whom he had always been a favourite, and lead henceforth a life of Arcadian simplicity. In this mood he wrote to Schuyler, in words which to-day seem strange and sad, that his ambition was not so much to “shine in history” as to be “a good citizen;” and about the 1st of January, 1779, he set out for Albany to consult with the New York legislature about the desired land.

Arnold’s scheme was approved by John Jay, who was then president of the Continental Congress, as well as by several other men of influence, and in all likelihood it would have succeeded; but as he stopped for a day at Morristown, to visit Washington, a letter overtook him, with the information that as soon as his back had been turned upon Philadelphia he had been publicly attacked by President Reed and the Council.

Charges are brought against him Jan., 1779Formal charges were brought against him: 1, of having improperly granted a pass for a ship to come into port; 2, of having once used some public wagons for the transportation of private property; 3, of having usurped the privilege of the Council in allowing people to enter the enemy’s lines; 4, of having illegally bought up a lawsuit over a prize vessel; 5, of having “imposed menial offices upon the sons of freemen” serving in the militia; and 6, of having made purchases for his private benefit at the time when, by his own order, all shops were shut. These charges were promulgated in a most extraordinary fashion. Not only were they laid before Congress, but copies of them were sent to the governors of all the states, accompanied by a circular letter from President Reed requesting the governors to communicate them to their respective legislatures. Arnold was naturally enraged at such an elaborate attempt to prepossess the public mind against him, but his first concern was for the possible effect it might have upon Miss Shippen. He instantly returned to Philadelphia, and demanded an investigation.

He is acquitted by a committee of Congress in MarchHe had obtained Washington’s permission to resign his command, but deferred acting upon it till the inquiry should have ended. The charges were investigated by a committee of Congress, and about the middle of March this committee brought in a report stating that all the accusations were groundless, save the two which related to the use of the wagons and the irregular granting of a pass; and since in these instances there was no evidence of wrong intent, the committee recommended an unqualified verdict of acquittal. Arnold thereupon, considering himself vindicated, resigned his command. But Reed now represented to Congress that further testimony was forthcoming, and urged that the case should be reconsidered. Accordingly, instead of acting upon the report of its committee, Congress referred the matter anew to a joint committee of Congress and the Assembly and Council of Pennsylvania.

The case is referred to a court-martial, April 3, 1779This joint committee shirked the matter by recommending that the case be referred to a court-martial, and this recommendation was adopted by Congress on the 3d of April. The vials of Arnold’s wrath were now full to overflowing; but he had no cause to complain of Miss Shippen, for their marriage took place in less than a week after this action of Congress. Washington, who sympathized with Arnold’s impatience, appointed the court-martial for the 1st of May, but the Council of Pennsylvania begged for more time to collect evidence. And thus, in one way and another, the summer and autumn were frittered away, so that the trial did not begin until the 19th of December. All this time Arnold kept clamouring for a speedy trial, and Washington did his best to soothe him while paying due heed to the representations of the Council.

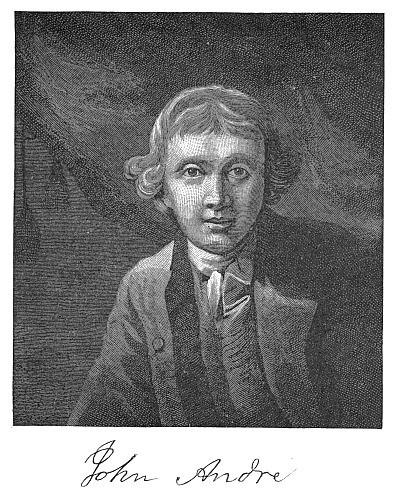

First correspondence with ClintonIn the excitement of this fierce controversy the Arcadian project seems to have been forgotten. Up to this point Arnold’s anger had been chiefly directed toward the authorities of Pennsylvania; but when Congress refused to act upon the report of its committee exonerating him from blame, he became incensed against the whole party which, as he said, had so ill requited his services. It is supposed to have been about that time, in April, 1779, that he wrote a letter to Sir Henry Clinton, in disguised handwriting and under the signature of “Gustavus,” describing himself as an American officer of high rank, who, through disgust at the French alliance and other recent proceedings of Congress, might perhaps be persuaded to go over to the British, provided he could be indemnified for any losses he might incur by so doing. The beginning of this correspondence – if this was really the time – coincided curiously with the date of Arnold’s marriage, but it is in the highest degree probable that down to the final catastrophe Mrs. Arnold knew nothing whatever of what was going on.[33] The correspondence was kept up at intervals, Sir Henry’s replies being written by Major John André, his adjutant-general, over the signature of “John Anderson.” Nothing seems to have been thought of at first beyond the personal desertion of Arnold to the enemy; the betrayal of a fortress was a later development of infamy. For the present, too, we may suppose that Arnold was merely playing with fire, while he awaited the result of the court-martial.

The summer was not a happy one. His debts went on increasing, while his accounts with Congress remained unsettled, and he found it impossible to collect large sums that were due him. At last the court-martial met, and sat for five weeks. On the 26th of January, 1780, the verdict was rendered, and in substance it agreed exactly with that of the committee of Congress ten months before. Arnold was fully acquitted of all the charges which alleged dishonourable dealings. The pass which he had granted was irregular, and public wagons, which were standing idle, had once been used to remove private property that was in imminent danger from the enemy. The court exonerated Arnold of all intentional wrong, even in these venial matters, which it characterized as “imprudent;” but, as a sort of lame concession to the Council of Pennsylvania, it directed that he should receive a public reprimand from the commander-in-chief for his imprudence in the use of wagons, and for hurriedly giving a pass in which all due forms were not attended to. The decision of the court-martial was promptly confirmed by Congress, and Washington had no alternative but to issue the reprimand, which he couched in words as delicate and gracious as possible.[34]

Arnold thirsts for revenge upon CongressIt was too late, however. The damage was done. Arnold had long felt persecuted and insulted. He had already dallied with temptation, and the poison was now working in his veins. His sense of public duty was utterly distorted by the keener sense of his private injuries. We may imagine him brooding over some memorable incidents in the careers of Monk, of the great Montrose and the greater Marlborough, until he persuaded himself that to change sides in a civil war was not so heinous a crime after all. Especially the example of Monk, which had already led Charles Lee to disgrace, seems to have riveted the attention of Arnold, although only the most shallow scrutiny could discover any resemblance between what the great English general had done and what Arnold purposed to do. There was not a more scrupulously honourable soldier in his day than George Monk. Arnold’s thoughts may have run somewhat as follows. He would not become an ordinary deserter, a villain on a small scale. He would not sell himself cheaply to the devil; but he would play as signal a part in his new career as he had played in the old one. He would overwhelm this blundering Congress, and triumphantly carry the country back to its old allegiance. To play such a part, however, would require the blackest treachery. Fancy George Monk, “honest old George,” asking for the command of a fortress in order to betray it to the enemy!

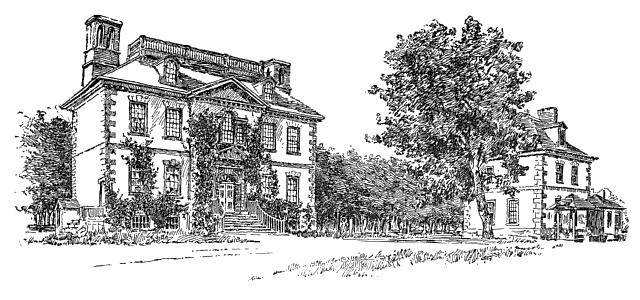

BENEDICT ARNOLD’S HOUSE AT PHILADELPHIA

When once Arnold had committed himself to this evil course, his story becomes a sickening one, lacking no element of horror, whether in its foul beginnings or in its wretched end. To play his new part properly, he must obtain an important command, and the place which obviously suggested itself was West Point.

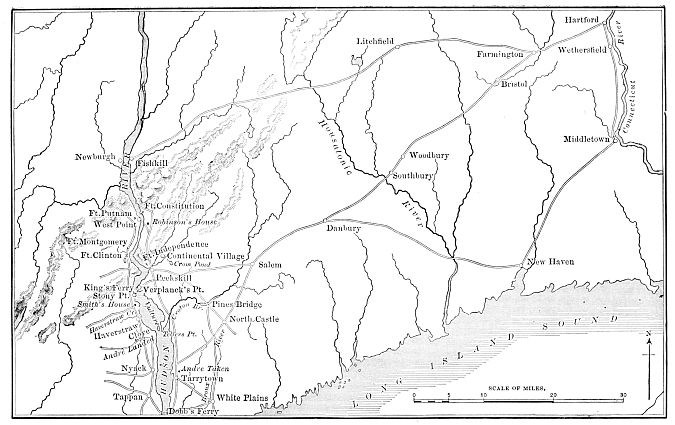

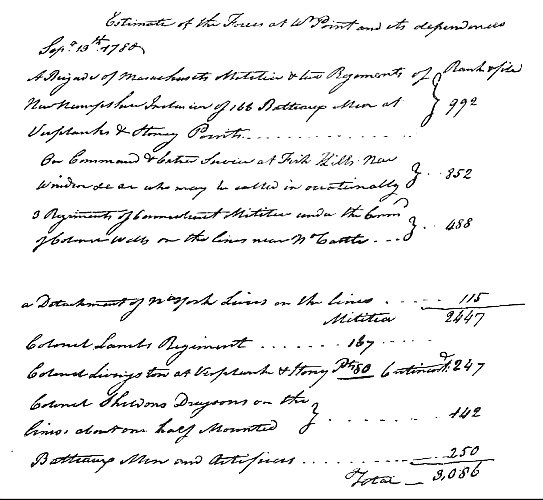

Significance of West PointSince Burgoyne’s overthrow, Washington had built a chain of strong fortresses there, for he did not intend that the possession of the Hudson river should ever again be put in question, so far as fortifications could go. Could this cardinal position be delivered up to Clinton, the prize would be worth tenfold the recent triumphs at Charleston and Camden. It would be giving the British what Burgoyne had tried in vain to get; and now it was the hero of Saratoga who plotted to undo his own good work at the dictates of perverted ambition and unhallowed revenge.

Arnold put in command of West Point, July, 1780To get possession of this stronghold, it was necessary to take advantage of the confidence with which his great commander had always honoured him. From Washington, in July, 1780, Arnold sought the command of West Point, alleging that his wounded leg still kept him unfit for service in the field; and Washington immediately put him in charge of this all-important post, thus giving him the strongest proof of unabated confidence and esteem which it was in his power to give; and among all the dark shades in Arnold’s treason, perhaps none seems darker than this personal treachery toward the man who had always trusted and defended him. What must the traitor’s feelings have been when he read the affectionate letters which Schuyler wrote him at this very time? In better days he had shown much generosity of nature. Can it be that this is the same man who on the field of Saratoga saved the life of the poor soldier who in honest fight had shot him and broken his leg? Such are the strange contrasts that we sometimes see in characters that are governed by impulse, and not by principle. Their virtue may be real enough while it lasts, but it does not weather the storm; and when once wrecked, the very same emotional nature by which alone it was supported often prompts to deeds of incredible wickedness.

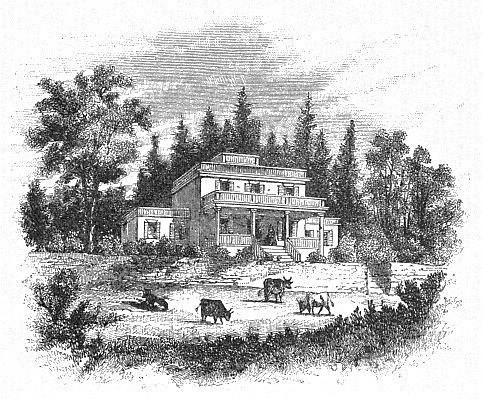

JOSHUA SMITH’S HOUSE, ON TREASON HILL

After taking command of West Point, the correspondence with André, carefully couched in such terms as to make it seem to refer to some commercial enterprise, was briskly kept up; and hints were let drop which convinced Sir Henry Clinton that the writer was Arnold, and the betrayal of the highland stronghold his purpose. Troops were accordingly embarked on the Hudson, and the flotilla was put in command of Admiral Rodney, who had looked in at New York on his way to the West Indies. To disguise the purpose of the embarkation, a rumour was industriously circulated that a force was to be sent southward to the Chesapeake.

Secret interview between Arnold and André, Sept. 22To arrange some important details of the affair it seemed desirable that the two correspondents “Gustavus” and “John Anderson,” should meet, and talk over matters which could not safely be committed to paper. On the 18th of September, Washington, accompanied by Lafayette and Hamilton, set out for Hartford, for an interview with Rochambeau; and advantage was taken of his absence to arrange a meeting between the plotters. On the 20th André was taken up the river on the Vulture, sloop-of-war, and on the night of the 21st Arnold sent out a boat which brought him ashore about four miles below Stony Point. There in a thicket of fir-trees, under the veil of blackest midnight, the scheme was matured; but as gray dawn came on before all the details had been arranged, the boatmen became alarmed, and refused to take André back to the ship, and he was accordingly persuaded, though against his will, to accompany Arnold within the American lines. The two conspirators walked up the bank a couple of miles to the house of one Joshua Smith, a man of doubtful allegiance, who does not seem to have understood the nature and extent of the plot, or to have known who Arnold’s visitor was. It was thought that they might spend the day discussing the enterprise, and when it should have grown dark André could be rowed back to the Vulture.

LINKS OF WEST POINT CHAIN

SCENE OF ARNOLD’S TREASON, 1780

The plot for surrendering West Point

But now a quite unforeseen accident occurred. Colonel Livingston, commanding the works on the opposite side of the river, was provoked by the sight of a British ship standing so near; and he opened such a lively fire upon the Vulture that she was obliged to withdraw from the scene. As the conspirators were waiting in Smith’s house for breakfast to be served, they heard the booming of the guns, and André, rushing to the window, beheld with dismay the ship on whose presence so much depended dropping out of sight down the stream. On second thoughts, however, it was clear that she would not go far, as her commander had orders not to return to New York without André, and it was still thought that he might regain her. After breakfast he went to an upper chamber with Arnold, and several hours were spent in perfecting their plans. Immediately upon André’s return to New York, the force under Clinton and Rodney was to ascend the river. To obstruct the approach of a hostile flotilla, a massive chain lay stretched across the river, guarded by water batteries. Under pretence of repairs, one link was to be taken out for a few days, and supplied by a rope which a slight blow would tear away. The approach of the British was to be announced by a concerted system of signals, and the American forces were to be so distributed that they could be surrounded and captured in detail, until at the proper moment Arnold, taking advantage of the apparent defeat, was to surrender the works, with all the troops – 3,000 in number – under his command. It was not unreasonably supposed that such a catastrophe, coming on the heels of Charleston and Camden and general bankruptcy, would put a stop to the war and lead to negotiations, in which Arnold, in view of such decisive service, might hope to play a leading part.

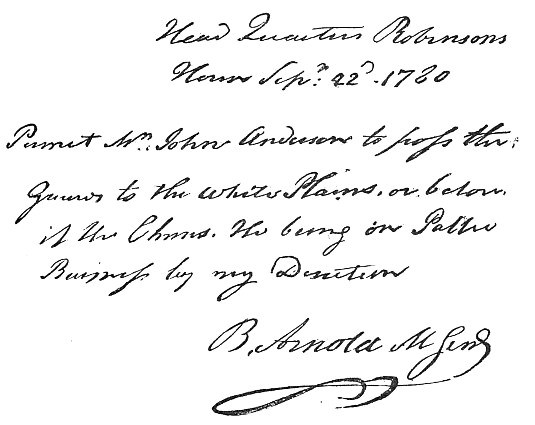

André takes compromising documentsWhen André set out on this perilous undertaking, Sir Henry Clinton specially warned him not to adopt any disguise or to carry any papers which might compromise his safety. But André disregarded the advice, and took from Arnold six papers, all but one of them in the traitor’s own handwriting, containing descriptions of the fortresses and information as to the disposition of the troops. Much risk might have been avoided by putting this information into cipher, or into a memorandum which would have been meaningless save to the parties concerned. But André may perhaps have doubted Arnold’s fidelity, and feared lest under a false pretence of treason he might be drawing the British away into a snare. The documents which he took, being in Arnold’s handwriting and unmistakable in their purport, were such as to put him in Clinton’s power, and compel him, for the sake of his own safety, to perform his part of the contract. André intended, before getting into the boat, to tie up these papers in a bundle loaded with a stone, to be dropped into the water in case of a sudden challenge; but in the mean time he put them where they could not so easily be got rid of, between his stockings and the soles of his feet. Arnold furnished the requisite passes for Smith and André to go either by boat or by land, and, having thus apparently provided for all contingencies, took leave before noon, and returned in his barge to his headquarters, ten miles up the stream. As evening approached, Smith, who seems to have been a man of unsteady nerves, refused to take André out to the Vulture.

and is reluctantly persuaded to return to New York by land, Sept. 22He had been alarmed by the firing in the morning, and feared there would be more risk in trying to reach the ship than in travelling down to the British lines by land, and he promised to ride all night with André if he would go that way. The young officer reluctantly consented, and partially disguised himself in some of Smith’s clothes. At sundown the two crossed the river at King’s Ferry, and pursued their journey on horseback toward White Plains.

FACSIMILE OF ARNOLD’S PASS TO ANDRÉ

The roads infested by robbers

The roads east of the Hudson, between the British and the American lines, were at this time infested by robbers, who committed their depredations under pretence of keeping up a partisan warfare. There were two sets of these scapegraces, – the “Cowboys,” or cattle-thieves, and the “Skinners,” who took everything they could find. These epithets, however, referred to the political complexion they chose to assume, rather than to any difference in their evil practices. The Skinners professed to be Whigs, and the Cowboys called themselves Tories; but in point of fact the two parties were alike political enemies to any farmer or wayfarer whose unprotected situation offered a prospect of booty; and though murder was not often committed, nobody’s property was safe. It was a striking instance of the demoralization wrought in a highly civilized part of the country through its having so long continued to be the actual seat of war. Rumours that the Cowboys were out in force made Smith afraid to continue the journey by night, and the impatient André was thus obliged to stop at a farmhouse with his timid companion. Rising before dawn, they kept on until they reached the Croton river, which marked the upper boundary of the neutral ground between the British and the American lines. Smith’s instructions had been, in case of adopting the land route, not to leave his charge before reaching White Plains; but he now became uneasy to return, and André, who was beginning to consider himself out of danger, was perhaps not unwilling to part with a comrade who annoyed him by his loquacious and inquisitive disposition. So Smith made his way back to headquarters, and informed Arnold that he had escorted “Mr. Anderson” within a few miles of the British lines, which he must doubtless by this time have reached in safety.

FACSIMILE OF ONE OF THE PAPERS FOUND IN ANDRÉ’S STOCKINGS

Arrest of André, Sept. 23

Meanwhile, André, left to himself, struck into the road which led through Tarrytown, expecting to meet no worse enemies than Cowboys, who would either respect a British officer, or, if bent on plunder, might be satisfied by his money and watch. But it happened that morning that a party of seven young men had come out to intercept some Cowboys who were expected up the road; and about nine o’clock, as André was approaching the creek above Tarrytown, a short distance from the far-famed Sleepy Hollow, he was suddenly confronted by three of this party, who sprang from the bushes and, with levelled muskets, ordered him to halt. These men had let several persons, with whose faces they were familiar, pass unquestioned; and if Smith, who was known to almost every one in that neighbourhood, had been with André, they too would doubtless have been allowed to pass. André was stopped because he was a stranger. One of these men happened to have on the coat of a Hessian soldier. Held by the belief that they must be Cowboys, or members of what was sometimes euphemistically termed the “lower party,” André expressed a hope that such was the case; and on being assured that it was so, his caution deserted him, and, with that sudden sense of relief which is apt to come after unwonted and prolonged constraint, he avowed himself a British officer, travelling on business of great importance. To his dismay, he now learned his mistake. John Paulding, the man in the Hessian coat, informed him that they were Americans, and ordered him to dismount. When he now showed them Arnold’s pass they disregarded it, and insisted upon searching him, until presently the six papers were discovered where he had hidden them. “By God, he is a spy!” exclaimed Paulding, as he looked over the papers. Threats and promises were of no avail. The young men, who were not to be bought or cajoled, took their prisoner twelve miles up the river, and delivered him into the hands of Colonel John Jameson, a Virginian officer, who commanded a cavalry outpost at North Castle. When Jameson looked over the papers, they seemed to him very extraordinary documents to be travelling toward New York in the stockings of a stranger who could give no satisfactory account of himself.