полная версия

полная версияThe American Revolution

The enormity of Arnold’s conduct stands out in all the stronger relief when we contrast with it the behaviour of the common soldiers whose mutiny furnished the next serious obstacle with which Washington had to contend at this period of the war.

Mutiny of Pennsylvania troops, Jan. 1, 1781In the autumn of 1780, owing to the financial and administrative chaos which had overtaken the country, the army was in a truly pitiable condition. The soldiers were clothed in rags and nearly starved, and many of them had not seen a dollar of pay since the beginning of the year. As the winter frosts came on there was much discontent, and the irritation was greatest among the soldiers of the Pennsylvania line who were encamped on the heights of Morristown. Many of these men had enlisted at the beginning of 1778, to serve “for three years or during the war;” but at that bright and hopeful period, just after the victory of Saratoga, nobody supposed that the war could last for three years more, and the alternative was inserted only to insure them against being kept in service for the full term of three years in spite of the cessation of hostilities. Now the three years had passed, the war was not ended, and the prospect seemed less hopeful than in 1778. The men felt that their contract was fulfilled and asked to be discharged. But the officers, unwilling to lose such disciplined troops, the veterans of Monmouth and Stony Point, insisted that the contract provided for three years’ service or more, in case the war should last longer; and they refused the requested discharge. On New Year’s Day, 1781, after an extra ration of grog, 1,300 Pennsylvania troops marched out of camp, in excellent order, under command of their sergeants, and seizing six field-pieces, set out for Philadelphia, with declared intent to frighten Congress and obtain redress for their wrongs. Their commander, General Wayne, for whom they entertained great respect and affection, was unable to stop them, and after an affray in which one man was killed and a dozen were wounded, they were perforce allowed to go on their way. Alarm guns were fired, couriers were sent to forewarn Congress and to notify Washington; and Wayne, attended by two colonels, galloped after the mutineers, to keep an eye upon them, and restrain their passions so far as possible. Washington could not come to attend to the affair in person, for the Hudson was not yet frozen and the enemy’s fleet was in readiness to ascend to West Point the instant he should leave his post. Congress sent out a committee from Philadelphia, accompanied by President Reed, to parley with the insurgents, who had halted at Princeton and were behaving themselves decorously, doing no harm to the people in person or property. They allowed Wayne and his colonels to come into their camp, but gave them to understand that they would take no orders from them. A sergeant-major acted as chief-commander, and his orders were implicitly obeyed. When Lafayette, with St. Clair and Laurens, came to them from Washington’s headquarters, they were politely but firmly told to go about their business. And so matters went on for a week. President Reed came as far as Trenton, and wrote to Wayne requesting an interview outside of Princeton, as he did not wish to come to the camp himself and run the risk of such indignity as that with which Washington’s officers had just been treated. As the troops assembled on parade Wayne read them this letter. Such a rebuke from the president of their native state touched these poor fellows in a sensitive point. Tears rolled down many a bronzed and haggard cheek. They stood about in little groups, talking and pondering and not half liking the business which they had undertaken.

At this moment it was discovered that two emissaries from Sir Henry Clinton were in the camp, seeking to tamper with the sergeant-major, and promising high pay, with bounties and pensions, if they would come over to Paulus Hook or Staten Island and cast in their lot with the British. In a fury of wrath the tempters were seized and carried to Wayne to be dealt with as spies. “We will have General Clinton understand,” said the men, “that we are not Benedict Arnolds!” Encouraged by this incident, President Reed came to the camp next day, and was received with all due respect. He proposed at once to discharge all those who had enlisted for three years or the war, to furnish them at once with such clothing as they most needed, and to give paper certificates for the arrears of their pay, to be redeemed as soon as possible. These terms, which granted unconditionally all the demands of the insurgents, were instantly accepted. All those not included in the terms received six weeks’ furlough, and thus the whole force was dissolved. The two spies were tried by court-martial and promptly hanged.

Further mutiny suppressedThe quickness with which the demands of these men were granted was an index to the alarm which their defection had excited; and Washington feared that their example would be followed by the soldiers of other states. On the 20th of January, indeed, a part of the New Jersey troops mutinied at Pompton, and declared their intention to do like the men of Pennsylvania. The case was becoming serious; it threatened the very existence of the army; and a sudden blow was needed. Washington sent from West Point a brigade of Massachusetts troops, which marched quickly to Pompton, surprised the mutineers before daybreak, and compelled them to lay down their arms without a struggle. Two of the ringleaders were summarily shot, and so the insurrection was quelled.

Thus the disastrous year which had begun when Clinton sailed against Charleston, the year which had witnessed the annihilation of two American armies and the bankruptcy of Congress, came at length to an end amid treason and mutiny. It had been the most dismal year of the war, and it was not strange that many Americans despaired of their country. Yet, as we have already seen, the resources of Great Britain, attacked as she was by the united fleets of France, Spain, and Holland, were scarcely less exhausted than those of the United States. The moment had come when a decided military success must turn the scale irrevocably the one way or the other; and events had already occurred at the South which were soon to show that all the disasters of 1780 were but the darkness that heralds the dawn.

CHAPTER XV

YORKTOWN

In the invasion of the South by Cornwallis, as in the invasion of the North by Burgoyne, the first serious blow which the enemy received was dealt by the militia. After his great victory over Gates, Cornwallis remained nearly a month at Camden resting his troops, who found the August heat intolerable.

Cornwallis invades North Carolina, Sept., 1780By the middle of September, 1780, he had started on his march to North Carolina, of which he expected to make an easy conquest. But his reception in that state was anything but hospitable. Advancing as far as Charlotte, he found himself in the midst of that famous Mecklenburg County which had issued its bold revolutionary resolves immediately on receiving the news of the battle of Lexington. These rebels, he said, were the most obstinate he had found in America, and he called their country a “hornet’s nest.” Bands of yeomanry lurking about every woodland road cut off his foraging parties, slew his couriers, and captured his dispatches. It was difficult for him to get any information; but bad news proverbially travels fast, and it was not long before he received intelligence of dire disaster.

Ferguson’s expeditionBefore leaving South Carolina Cornwallis had detached Major Patrick Ferguson – whom, next to Tarleton, he considered his best partisan officer – to scour the highlands and enlist as large a force of Tory auxiliaries as possible, after which he was to join the main army at Charlotte. Ferguson took with him 200 British light infantry and 1,000 Tories, whom he had drilled until they had become excellent troops. It was not supposed that he would meet with serious opposition, but in case of any unforeseen danger he was to retreat with all possible speed and join the main army. Now the enterprising Ferguson undertook to entrap and capture a small force of American partisans; and while pursuing this bait, he pushed into the wilderness as far as Gilbert Town, in the heart of what is now the county of Rutherford, when all at once he became aware that enemies were swarming about him on every side.

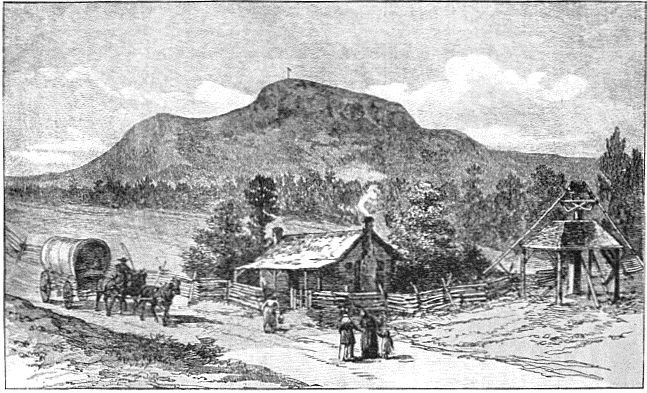

Rising of the backwoodsmenThe approach of a hostile force and the rumour of Indian war had aroused the hardy backwoodsmen who dwelt in these wild and romantic glens. Accustomed to Indian raids, these quick and resolute men were always ready to assemble at a moment’s warning; and now they came pouring from all directions, through the defiles of the Alleghanies, a picturesque and motley crowd, in fringed and tasselled hunting-shirts, with sprigs of hemlock in their hats, and armed with long knives and rifles that seldom missed their aim. From the south came James Williams, of Ninety-Six, with his 400 men; from the north, William Campbell, of Virginia, Benjamin Cleveland and Charles McDowell, of North Carolina, with 560 followers; from the west, Isaac Shelby and John Sevier, whose names were to become so famous in the early history of Kentucky and Tennessee. By the 30th of September 3,000 of these “dirty mongrels,” as Ferguson called them, – men in whose veins flowed the blood of Scottish Covenanters and French Huguenots and English sea rovers,[39]– had gathered in such threatening proximity that the British commander started in all haste on his retreat toward the main army at Charlotte, sending messengers ahead, who were duly waylaid and shot down before they could reach Cornwallis and inform him of the danger. The pursuit was vigorously pressed, and on the night of the 6th of October, finding escape impossible without a fight, Ferguson planted himself on the top of King’s Mountain, a ridge about half a mile in length and 1,700 feet above sea level, situated just on the border line between the two Carolinas. The crest is approached on three sides by rising ground, above which the steep summit towers for a hundred feet; on the north side it is an unbroken precipice. The mountain was covered with tall pine-trees, beneath which the ground, though little cumbered with underbrush, was obstructed on every side by huge moss-grown boulders. Perched with 1,125 staunch men on this natural stronghold, as the bright autumn sun came up on the morning of the 7th, Ferguson looked about him exultingly, and cried, “Well, boys, here is a place from which all the rebels outside of hell cannot drive us!”

He was dealing, however, with men who were used to climbing hills. About three o’clock in the afternoon, the advanced party of Americans, 1,000 picked men, arrived in the ravine below the mountain, and, tying their horses to the trees, prepared to storm the position. The precipice on the north was too steep for the enemy to descend, and thus effectually cut off their retreat. Divided into three equal parties, the Americans ascended the other three sides simultaneously. Campbell and Shelby pushed up in front until near the crest, when Ferguson opened fire on them. They then fell apart behind trees, returning the fire most effectively, but suffering little themselves, while slowly they crept up nearer the crest. As the British then charged down upon them with bayonets, they fell back, until the British ranks were suddenly shaken by a deadly flank fire from the division of Sevier and McDowell on the right. Turning furiously to meet these new assailants, the British received a volley in their backs from the left division, under Cleveland and Williams, while the centre division promptly rallied, and attacked them on what was now their flank. Thus dreadfully entrapped, the British fired wildly and with little effect, while the trees and boulders prevented the compactness needful for a bayonet charge. The Americans, on the other hand, sure of their prey, crept on steadily toward the summit, losing scarcely a man, and firing with great deliberateness and precision, while hardly a word was spoken. As they closed in upon the ridge, a rifleball pierced the brave Ferguson’s heart, and he fell from his white horse, which sprang wildly down the mountain side. All further resistance being hopeless, a white flag was raised, and the firing was stopped. Of Ferguson’s 1,125 men, 389 were killed or wounded, 20 were missing, and the remaining 716 now surrendered themselves prisoners of war, with 1,500 stand of arms. The total American loss was 28 killed and 60 wounded; but among the killed was the famous partisan commander, James Williams, whose loss might be regarded as offsetting that of Major Ferguson.

VIEW OF KING’S MOUNTAIN

Effect of the blow

This brilliant victory at King’s Mountain resembled the victory at Bennington in its suddenness and completeness, as well as in having been gained by militia. It was also the harbinger of greater victories at the South, as Bennington had been the harbinger of greater victories at the North. The backwoodsmen who had dealt such a blow did not, indeed, follow it up, and hover about the flanks of Cornwallis, as the Green Mountain boys had hovered about the flanks of Burgoyne. Had there been an organized army opposed to Cornwallis, to serve as a nucleus for them, perhaps they might have done so. As it was, they soon dispersed and returned to their homes, after having sullied their triumph by hanging a dozen prisoners, in revenge for some of their own party who had been massacred at Augusta. They had, nevertheless, warded off for the moment the threatened invasion of North Carolina. Thoroughly alarmed by this blow, Cornwallis lost no time in falling back upon Winnsborough, there to wait for reinforcements, for he was in no condition to afford the loss of 1,100 men. General Leslie had been sent by Sir Henry Clinton to Virginia with 3,000 men, and Cornwallis ordered this force to join him without delay.

Arrival of Daniel MorganHope began now to return to the patriots of South Carolina, and during the months of October and November their activity was greatly increased. Marion in the northeastern part of the state, and Sumter in the northwest, redoubled their energies, and it was more than even Tarleton could do to look after them both. On the 20th of November Tarleton was defeated by Sumter in a sharp action at Blackstock Hill, and the disgrace of the 18th of August was thus wiped out. On the retreat of Cornwallis, the remnants of the American regular army, which Gates had been slowly collecting at Hillsborough, advanced and occupied Charlotte. There were scarcely 1,400 of them, all told, and their condition was forlorn enough. But reinforcements from the North were at hand; and first of all came Daniel Morgan, always a host in himself. Morgan, like Arnold, had been ill treated by Congress. His services at Quebec and Saratoga had been inferior only to Arnold’s, yet, in 1779, he had seen junior officers promoted over his head, and had resigned his commission and retired to his home in Virginia. When Gates took command of the southern army, Morgan was urged to enter the service again; but, as it was not proposed to restore him to his relative rank, he refused. After Camden, however, declaring that it was no time to let personal considerations have any weight, he straightway came down and joined Gates at Hillsborough in September. At last, on the 13th of October, Congress had the good sense to give him the rank to which he was entitled; and it was not long, as we shall see, before it had reason to congratulate itself upon this act of justice.

Greene appointed to the chief command at the SouthBut, more than anything else, the army which it was now sought to restore needed a new commander-in-chief. It was well known that Washington had wished to have Greene appointed to that position, in the first place. Congress had persisted in appointing its own favourite instead, and had lost an army in consequence. It could now hardly do better, though late in the day, than take Washington’s advice. It would not do to run the risk of another Camden. In every campaign since the beginning of the war Greene had been Washington’s right arm; and for indefatigable industry, for strength and breadth of intelligence, and for unselfish devotion to the public service, he was scarcely inferior to the commander-in-chief. Yet he too had been repeatedly insulted and abused by men who liked to strike at Washington through his favourite officers. As quartermaster-general, since the spring of 1778, Greene had been malevolently persecuted by a party in Congress, until, in July, 1780, his patience gave way, and he resigned in disgust. His enemies seized the occasion to urge his dismissal from the army, and but for his own keen sense of public duty and Washington’s unfailing tact his services might have been lost to the country at a most critical moment. On the 5th of October Congress called upon Washington to name a successor to Gates, and he immediately appointed Greene, who arrived at Charlotte and took command on the 2d of December. Steuben accompanied Greene as far as Virginia, and was placed in command in that state, charged with the duty of collecting and forwarding supplies and reinforcements to Greene, and of warding off the forces which Sir Henry Clinton sent to the Chesapeake to make diversions in aid of Cornwallis. The first force of this sort, under General Leslie, had just been obliged to proceed by sea to South Carolina, to make good the loss inflicted upon Cornwallis by the battle of King’s Mountain; and to replace Leslie in Virginia, Sir Henry Clinton, in December, sent the traitor Arnold, fresh from the scene of his treason, with 1,600 men, mostly New York loyalists. Steuben’s duty was to guard Virginia against Arnold, and to keep open Greene’s communication with the North. At the same time, Washington sent down with Greene the engineer Kosciuszko and Henry Lee with his admirable legion of cavalry. Another superb cavalry commander now appears for the first time upon the scene in the person of Lieutenant-Colonel William Washington, of Virginia, a distant cousin of the commander-in-chief.

The southern army, though weak in numbers, was thus extraordinarily strong in the talent of its officers. They were men who knew how to accomplish great results with small means, and Greene understood how far he might rely upon them. No sooner had he taken command than he began a series of movements which, though daring in the extreme, were as far as possible from partaking of the unreasoned rashness which had characterized the advance of Gates. That unintelligent commander had sneered at cavalry as useless, but Greene largely based his plan of operations upon what could be done by such swift blows as Washington and Lee knew how to deal. Gates had despised the aid of partisan chiefs, but Greene saw at once the importance of utilizing such men as Sumter and Marion. His army as a solid whole was too weak to cope with that of Cornwallis. By a bold and happy thought, he divided it, for the moment, into two great partisan bodies. The larger body, 1,100 strong, he led in person to Cheraw Hill, on the Pedee river, where he coöperated with Marion. From this point Marion and Lee kept up a series of rapid movements which threatened Cornwallis’s communications with the coast. On one occasion, they actually galloped into Georgetown and captured the commander of that post. Cornwallis was thus gravely annoyed, but he was unable to advance upon these provoking antagonists without risking the loss of Augusta and Ninety-Six; for Greene had thrown the other part of his little army, 900 strong, under Morgan, to the westward, so as to threaten those important inland posts and to coöperate with the mountain militia. With Morgan’s force went William Washington, who accomplished a brilliant raid, penetrating the enemy’s lines, and destroying a party of 250 men at a single blow.

Thus worried and menaced upon both his flanks, Cornwallis hardly knew which way to turn. He did not underrate his adversaries. He had himself seen what sort of man Greene was, at Princeton and Brandywine and Germantown, while Morgan’s abilities were equally well known. He could not leave Morgan and attack Greene without losing his hold upon the interior; but if he were to advance in full force upon Morgan, the wily Greene would be sure to pounce upon Charleston and cut him off from the coast. In this dilemma, Cornwallis at last decided to divide his own forces. With his main body, 2,000 strong, he advanced into North Carolina, hoping to draw Greene after him; while he sent Tarleton with the rest of his army, 1,100 strong, to take care of Morgan. By this division the superiority of the British force was to some extent neutralized. Both commanders were playing a skilful but hazardous game, in which much depended on the sagacity of their lieutenants; and now the brave but over-confident Tarleton was outmarched and outfought. On his approach, Morgan retreated to a grazing ground known as the Cowpens, a few miles from King’s Mountain, where he could fight on ground of his own choosing. His choice was indeed a peculiar one, for he had a broad river in his rear, which cut off retreat; but this, he said, was just what he wanted, for his militia would know that there was no use in running away.

Morgan’s position at the CowpensIt was cheaper than stationing regulars in the rear, to shoot down the cowards. Morgan’s daring was justified by the result. The ground, a long rising slope, commanded the enemy’s approach for a great distance. On the morning of January 17, 1781, as Tarleton’s advance was descried, Morgan formed his men in order of battle. First he arranged his Carolinian and Georgian militia in a line about three hundred yards in length, and exhorted them not to give way until they should have delivered at least two volleys “at killing distance.” One hundred and fifty yards in the rear of this line, and along the brow of the gentle hill, he stationed the splendid Maryland brigade which Kalb had led at Camden, and supported it by some excellent Virginia troops. Still one hundred and fifty yards farther back, upon a second rising ground, he placed Colonel Washington with his cavalry. Arranged in this wise, the army awaited the British attack.

Battle of the Cowpens, Jan. 17, 1781Tarleton’s men had been toiling half the night over muddy roads and wading through swollen brooks, but nothing could restrain his eagerness to strike a sudden blow, and just about sunrise he charged upon the first American line. The militia, who were commanded by the redoubtable Pickens, behaved very well, and delivered, not two, but many deadly volleys at close range, causing the British lines to waver for a moment. As the British recovered themselves and pressed on, the militia retired behind the line of Continentals; while the British line, in pursuing, became so extended as to threaten the flanks of the Continental line. To avoid being overlapped, the Continentals refused their right wing and fell back a little. The British followed them hastily and in some confusion, having become too confident of victory. At this moment, Colonel Washington, having swept down from his hill in a semicircle, charged the British right flank with fatal effect; Pickens’s militia, who had reformed in the rear and marched around the hill, advanced upon their left flank; while the Continentals, in front, broke their ranks with a deadly fire at thirty yards, and instantly rushed upon them with the bayonet.

Destruction of Tarleton’s forceThe greater part of the British army thereupon threw down their arms and surrendered, while the rest were scattered in flight. It was a complete rout. The British lost 230 in killed and wounded, 600 prisoners, two field-pieces, and 1,000 stand of arms. Their loss was about equal to the whole American force engaged. Only 270 escaped from the field, among them Tarleton, who barely saved himself in a furious single combat with Washington. The American loss, in this astonishing little battle, was 12 killed and 61 wounded. In point of tactics, it was the most brilliant battle of the war. Morgan had in him the divine spark of genius.