полная версия

полная версияThe American Revolution

But so far from his suspecting Arnold of any complicity in the matter, he could think of nothing better than to send the prisoner straightway to Arnold himself, together with a brief letter in which he related what had happened. To the honest Jameson it seemed that this must be some foul ruse of the enemy, some device for stirring up suspicion in the camp, – something, at any rate, which could not too quickly be brought to his general’s notice. But the documents themselves he prudently sent by an express-rider to Washington, accompanying them with a similar letter of explanation. André, in charge of a military guard, had already proceeded some distance toward West Point when Jameson’s second in command, Major Benjamin Tallmadge, came in from some errand on which he had been engaged. On hearing what had happened, Tallmadge suspected that all was not right with Arnold, and insisted that André and the letter should be recalled. After a hurried discussion, Jameson sent out a party which brought André back; but he still thought it his duty to inform Arnold, and so the letter which saved the traitor’s life was allowed to proceed on its way.

BEVERLY ROBINSON’S HOUSE

Washington returns from Hartford sooner than expected

Now, if Washington had returned from Hartford by the route which it was supposed he would take, through Danbury and Peekskill, Arnold would not even thus have been saved. For some reason Washington returned two or three days sooner than had been expected; and, moreover, he chose a more northerly route, through Farmington and Litchfield, so that the messenger failed to meet him. It was on the evening of Saturday, the 23d, that Jameson’s two letters started. On Sunday afternoon Washington arrived at Fishkill, eighteen miles above West Point, and was just starting down the river road when he met Luzerne, the French minister, who was on his way to consult with Rochambeau. Wishing to have a talk with this gentleman, Washington turned back to the nearest inn, where they sat down to supper and chatted, all unconsciously, with the very Joshua Smith from whom André had parted at the Croton river on the morning of the day before. Word was sent to Arnold to expect the commander-in-chief and his suite to breakfast the next morning, and before daybreak of Monday they were galloping down the wooded road. As they approached the confiscated country house of the loyalist Beverly Robinson, where Arnold had his headquarters, opposite West Point, Washington turned his horse down toward the river, whereat Lafayette reminded him that they were late already, and ought not to keep Mrs. Arnold waiting. “Ah, marquis,” said Washington, laughing, “I know you young men are all in love with Mrs. Arnold: go and get your breakfast, and tell her not to wait for me.” Lafayette did not adopt the suggestion. He accompanied Washington and Knox while they rode down to examine some redoubts. Hamilton and the rest of the party kept on to the house, and sat down to breakfast in its cheerful wainscoted dining-room, with Arnold and his wife and several of his officers.

STAIRCASE IN ROBINSON’S HOUSE

Flight of Arnold, Sept. 25

As they sat at table, a courier entered, and handed to Arnold the letter in which Colonel Jameson informed him that one John Anderson had been taken with compromising documents in his possession, which had been forwarded to the commander-in-chief. With astonishing presence of mind, Arnold folded the letter and put it in his pocket, finished the remark which had been on his lips when the courier entered, and then, rising, said that he was suddenly called across the river to West Point, but would return to meet Washington without delay; and he ordered his barge to be manned. None of the officers observed anything unusual in his manner, but the quick eye of his wife detected something wrong, and as he left the room she excused herself and hurried after him. Going up to their bedroom, he told her that he was a ruined man and must fly for his life; and as she screamed and fainted in his arms, he laid her upon the bed, called in the maid to attend her, stooped to kiss his baby boy who was sleeping in the cradle, rushed down to the yard, leaped on a horse that was standing there, and galloped down a by-path to his barge. It had promptly occurred to his quick mind that the Vulture would still be waiting for André some miles down stream, and he told the oarsmen to row him thither without delay, as he must get back soon to meet Washington. A brisk row of eighteen miles brought them to the Vulture, whose commander was still wondering why André did not come back. From the cabin of the Vulture Arnold sent a letter to Washington, assuring him of Mrs. Arnold’s innocence, and begging that she might be allowed to return to her family in Philadelphia, or come to her husband, as she might choose. Then the ill-omened ship weighed anchor, and reached New York next morning.

MRS. BENEDICT ARNOLD AND CHILD

Discovery of the treasonable plot

Meanwhile, about noonday Washington came in for his breakfast, and, hearing that Arnold had crossed the river to West Point, soon hurried off to meet him there, followed by all his suite except Hamilton. As they were ferried across, no salute of cannon greeted them, and on landing they learned with astonishment that Arnold had not been there that morning; but no one as yet had a glimmer of suspicion. When they returned to Robinson’s house, about two o’clock, they found Hamilton walking up and down before the door in great excitement. Jameson’s courier had arrived, with the letters for Washington, which Hamilton had just opened and read. The commander and his aide went into the house, and together examined the papers, which, taken in connection with the traitor’s flight, but too plainly told the story. From Mrs. Arnold, who was in hysterics, Washington could learn nothing. He privately sent Hamilton and another aide in pursuit of the fugitive; and coming out to meet Lafayette and Knox, his voice choking and tears rolling down his cheeks, he exclaimed, “Arnold is a traitor, and has fled to the British! Whom can we trust now?” In a moment, however, he had regained his wonted composure. It was no time for giving way to emotion. It was as yet impossible to tell how far the scheme might have extended. Even now the enemy’s fleet might be ascending the river (as but for André’s capture it doubtless would have been doing that day), and an attack might be made before the morrow. Riding anxiously about the works, Washington soon detected the treacherous arrangements that had been made, and by seven in the evening he had done much to correct them and to make ready for an attack. As he was taking supper in the room which Arnold had so hastily quitted in the morning, the traitor’s letter from the Vulture was handed him. “Go to Mrs. Arnold,” said he quietly to one of his officers, “and tell her that though my duty required no means should be neglected to arrest General Arnold, I have great pleasure in acquainting her that he is now safe on board a British vessel.”

André taken to Tappan, Sept. 28But while the principal criminal was safe it was far otherwise with the agent who had been employed in this perilous business. On Sunday, from his room in Jameson’s quarters, André had written a letter to Washington, pathetic in its frank simplicity, declaring his position in the British army, and telling his story without any attempt at evasion. From the first there could be no doubt as to the nature of his case, yet André for the moment did not fully comprehend it. On Thursday, the 28th, he was taken across the river to Tappan, where the main army was encamped. His escort, Major Tallmadge, was a graduate of Yale College and a classmate of Nathan Hale, whom General Howe had hanged as a spy four years before. Tallmadge had begun to feel a warm interest in André, and as they rode their horses side by side into Tappan, when his prisoner asked how his case would probably be regarded, Tallmadge’s countenance fell, and it was not until the question had been twice repeated that he replied by a gentle allusion to the fate of his lamented classmate. “But surely,” said poor André, “you do not consider his case and mine alike!” “They are precisely similar,” answered Tallmadge gravely, “and similar will be your fate.”

Next day a military commission of fourteen generals was assembled, with Greene presiding, to sit in judgment on the unfortunate young officer. “It is impossible to save him,” said the kindly Steuben, who was one of the judges. “Would to God the wretch who has drawn him to his death might be made to suffer in his stead!” The opinion of the court was unanimous that André had acted as a spy, and incurred the penalty of death. Washington allowed a brief respite, that Sir Henry Clinton’s views might be considered. The British commander, in his sore distress over the danger of his young friend, could find no better grounds to allege in his defence than that he had, presumably, gone ashore under a flag of truce, and that when taken he certainly was travelling under the protection of a pass which Arnold, in the ordinary exercise of his authority, had a right to grant. But clearly these safeguards were vitiated by the treasonable purpose of the commander who granted them, and in availing himself of them André, who was privy to this treasonable purpose, took his life in his hands as completely as any ordinary spy would do. André himself had already candidly admitted before the court “that it was impossible for him to suppose that he came ashore under the sanction of a flag;” and Washington struck to the root of the matter, as he invariably did, in his letter to Clinton, where he said that André “was employed in the execution of measures very foreign to the objects of flags of truce, and such as they were never meant to authorize or countenance in the most distant degree.” The argument was conclusive, but it was not strange that the British general should have been slow to admit its force. He begged that the question might be submitted to an impartial committee, consisting of Knyphausen from the one army and Rochambeau from the other; but as no question had arisen which the military commission was not thoroughly competent to decide, Washington very properly refused to permit such an unusual proceeding. Lastly, Clinton asked that André might be exchanged for Christopher Gadsden, who had been taken in the capture of Charleston, and was then imprisoned at St. Augustine. At the same time, a letter from Arnold to Washington, with characteristic want of tact, hinting at retaliation upon the persons of sundry South Carolinian prisoners, was received with silent contempt.

Captain Ogden’s message, Sept. 30There was a general feeling in the American army that if Arnold himself could be surrendered to justice, it might perhaps be well to set free the less guilty victim by an act of executive clemency; and Greene gave expression to this feeling in an interview with Lieutenant-General Robertson, whom Clinton sent up on Sunday, the 1st of October, to plead for André’s life. No such suggestion could be made in the form of an official proposal. Under no circumstances could Clinton be expected to betray the man from whose crime he had sought to profit, and who had now thrown himself upon him for protection. Nevertheless, in a roundabout way the suggestion was made. On Saturday, Captain Ogden, with an escort of twenty-five men and a flag of truce, was sent down to Paulus Hook with letters for Clinton, and he contrived to whisper to the commandant there that if in any way Arnold might be suffered to slip into the hands of the Americans André would be set free. It was Lafayette who had authorized Ogden to offer the suggestion, and so, apparently Washington must have connived at it; but Clinton of course refused to entertain the idea for a moment.[35] The conference between Greene and Robertson led to nothing.

Execution of André, Oct. 2A petition from André, in which he begged to be shot rather than hanged, was duly considered and rejected; and, accordingly, on Monday, the 2d of October, the ninth day after his capture by the yeomen at Tarrytown, the adjutant-general of the British army was led to the gallows. His remains were buried near the spot where he suffered, but in 1821 they were disinterred and removed to Westminster Abbey.

FACSIMILE OF SKETCH OF ANDRÉ BY HIMSELF

The fate of this gallant young officer has always called forth tender commiseration, due partly to his high position and his engaging personal qualities, but chiefly, no doubt, to the fact that, while he suffered the penalty of the law, the chief conspirator escaped. One does not easily get rid of a vague sense of injustice in this, but the injustice was not of man’s contriving. But for the remarkable series of accidents – if it be philosophical to call them so – resulting in André’s capture, the treason would very likely have been successful, and the cause of American independence might have been for the moment ruined. But for an equally remarkable series of accidents Arnold would not have received warning in time to escape. If both had been captured, both would probably have been hanged. Certainly both alike had incurred the penalty of death. It was not the fault of Washington or of the military commission that the chief offender went unpunished, and in no wise was André made a scapegoat for Arnold.

Lord Stanhope’s unconscious impudenceIt is right that we should feel pity for the fate of André; but it is unfortunate that pity should be permitted to cloud the judgment of the historian, as in the case of Lord Stanhope, who stands almost alone among competent writers in impugning the justice of André’s sentence. One remark of Lord Stanhope’s I am tempted to quote, as an amusing instance of that certain air of “condescension” which James Russell Lowell once observed in our British cousins. He seeks to throw discredit upon the military commission by gravely assuming that the American generals must, of course, have been ignorant men, “who had probably never so much as heard the names of Vattel or Puffendorf,” and, accordingly, “could be no fit judges on any nice or doubtful point” of military law. Now, of the twelve American generals who sat in judgment on André, at least seven were men of excellent education. Two of them had taken degrees at Harvard, and two at English universities. Greene, the president, a self-educated man, who used, in leisure moments, to read Latin poets by the light of his camp-fire, had paid especial attention to military law, and had carefully read and copiously annotated his copy of Vattel. The judgment of these twelve men agreed with that of the two educated Europeans, Steuben and Lafayette, who sat with them on the commission; and, moreover, no nice or intricate questions were raised.

There is no reason in the world why André should have been sparedIt was natural enough that André’s friends should make the most of the fact that when captured he was travelling under a pass granted by the commander of West Point; but to ask the court to accept such a plea was not introducing any nice or doubtful question; it was simply contending that “the wilful abuse of a privilege is entitled to the same respect as its legitimate exercise.” Accordingly, historians on both sides of the Atlantic have generally admitted the justice of Andre’s sentence, though sometimes its rigorous execution has been censured as an act of unnecessary severity. Yet if we withdraw our attention for a moment from the irrelevant fact that the British adjutant-general was an amiable and interesting young man, and concentrate it upon the essential fact that he had come within our lines to aid a treacherous commander in betraying his post, we cannot fail to see that there is no principle of military policy upon which ordinary spies are rigorously put to death which does not apply with redoubled force to the case of André. Moreover, while it is an undoubted fact that military morality permits, and sometimes applauds, such enterprises as that in which André lost his life, I cannot but feel that the flavour of treachery which clings about it must somewhat weaken the sympathy we should otherwise freely accord; and I find myself agreeing with the British historian, Mr. Massey, when he doubts “whether services of this character entitle his memory to the honours of Westminster Abbey.”

Captain Battersby’s storyAs for Arnold, his fall had been as terrible as that of Milton’s rebellious archangel, and we may well believe his state of mind to have been desperate. It was said that on hearing of Captain Ogden’s suggestion as to the only possible means of saving André, Arnold went to Clinton and offered to surrender himself as a ransom for his fellow-conspirator. This story was published in the London “Morning Herald” in February, 1782, by Captain Battersby, of the 29th regiment, – one of the “Sam Adams” regiments. Battersby was in New York in September, 1780, and was on terms of intimacy with members of Clinton’s staff. In the absence of further evidence, one must beware of attaching too much weight to such a story. Yet it is not inconsistent with what we know of Arnold’s impulsive nature. In the agony of his sudden overthrow it may well have seemed that there was nothing left to live for, and a death thus savouring of romantic self-sacrifice might serve to lighten the burden of his shame as nothing else could. Like many men of weak integrity, Arnold was over-sensitive to public opinion, and his treason, as he had planned it, though equally indefensible in point of morality, was something very different from what it seemed now that it was frustrated. It was not for this that he had bartered his soul to Satan.

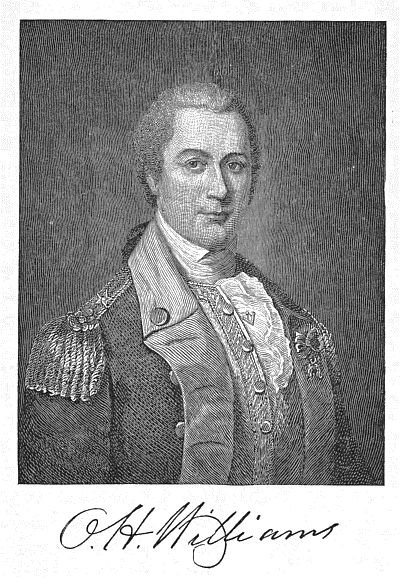

Arnold’s terrible downfallHe had aimed at an end so vast that, when once attained, it might be hoped that the nefarious means employed would be overlooked, and that in Arnold, the brilliant general who had restored America to her old allegiance, posterity would see the counterpart of that other general who, for bringing back Charles Stuart to his father’s throne, was rewarded with the dukedom of Albemarle. Now he had lost everything, and got nothing in exchange but £6,000 sterling and a brigadiership in the British army.[36] He had sold himself cheap, after all, and incurred such hatred and contempt that for a long time, by a righteous retribution, even his past services were forgotten. Even such weak creatures as Gates could now point the finger of scorn at him, while Washington, his steadfast friend, could never speak of him again without a shudder. From men less reticent than Washington strong words were heard. “What do you think of the damnable doings of that diabolical dog?” wrote Colonel Otho Williams with sturdy alliteration to Arnold’s old friend and fellow in the victory of Saratoga, Daniel Morgan. “Curse on his folly and perfidy,” said Greene, “how mortifying to think that he is a New Englander!” These were the men who could best appreciate the hard treatment Arnold had received from Congress. But in the frightful abyss of his crime all such considerations were instantly swallowed up and lost. No amount of personal wrong could for a moment excuse or even palliate such a false step as he had taken.

ANDRÉ’S POCKETBOOK

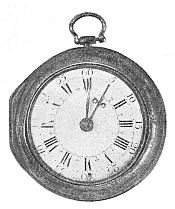

ARNOLD’S WATCH

Within three months from the time when his treason was discovered, Arnold was sent by Sir Henry Clinton on a marauding expedition into Virginia, and in the course of one of his raids an American captain was taken prisoner. “What do you suppose my fate would be,” Arnold is said to have inquired, “if my misguided countrymen were to take me prisoner?” The captain’s reply was prompt and frank: “They would cut off the leg that was wounded at Quebec and Saratoga and bury it with the honours of war, and the rest of you they would hang on a gibbet.” After the close of the war, when Arnold, accompanied by his wife, made England his home, it is said that he sometimes had to encounter similar expressions of contempt. The Earl of Surrey once, seeing him in the gallery of the House of Commons, asked the Speaker to have him put out, that the House might not be contaminated by the presence of such a traitor. The story is not well authenticated; but it is certain that in 1792 the Earl of Lauderdale used such language about him in the House of Lords as to lead to a bloodless duel between Arnold and the noble earl. It does not appear, however, that Arnold was universally despised in England. Influenced by the political passions of the day, many persons were ready to judge him leniently; and his generous and affectionate nature won him many friends. It is said that so high-minded a man as Lord Cornwallis became attached to him, and always treated him with respect.

Arnold’s familyMrs. Arnold proved herself a devoted wife and mother;[37] and the record of her four sons, during long years of service in the British army, was highly honourable. The second son, Lieutenant-General Sir James Robertson Arnold, served with distinction in the wars against Napoleon. A grandson who was killed in the Crimean war was especially mentioned by Lord Raglan for valour and skill. Another grandson, the Rev. Edward Arnold, who died in 1887, was rector of Great Massingham, in Norfolk. The family has intermarried with the peerage, and has secured for itself an honourable place among the landed gentry of England. But the disgrace of their ancestor has always been keenly felt by them. At Surinam, in 1804, James Robertson Arnold, then a lieutenant, begged the privilege of leading a desperate forlorn hope, that he might redeem the family name from the odium which attached to it; and he acquitted himself in a way that was worthy of his father in the days of Quebec and Saratoga. All the family tradition goes to show that the last years of Benedict Arnold in London were years of bitter remorse and self-reproach. The great name which he had so gallantly won and so wretchedly lost left him no repose by night or day. The iron frame, which had withstood the fatigue of so many trying battlefields and still more trying marches through the wilderness, broke down at last under the slow torture of lost friendships and merited disgrace.

His remorse and death, June 14, 1801In the last sad days in London, in June, 1801, the family tradition says that Arnold’s mind kept reverting to his old friendship with Washington. He had always carefully preserved the American uniform which he wore on the day when he made his escape to the Vulture; and now as, broken in spirit and weary of life, he felt the last moments coming, he called for this uniform and put it on, and decorated himself with the epaulettes and sword-knot which Washington had given him after the victory of Saratoga. “Let me die,” said he, “in this old uniform in which I fought my battles. May God forgive me for ever putting on any other!”

As we thus reach the end of one of the saddest episodes in American history, our sympathy cannot fail for the moment to go out toward the sufferer, nor can we help contrasting these passionate dying words with the last cynical scoff of that other traitor, Charles Lee, when he begged that he might not be buried within a mile of any church, as he did not wish to keep bad company after death. From beginning to end the story of Lee is little more than a vulgar melodrama; but into the story of Arnold there enters that element of awe and pity which, as Aristotle pointed out, is an essential part of real tragedy. That Arnold had been very shabbily treated, long before any thought of treason entered his mind, is not to be denied. That he may honestly have come to consider the American cause hopeless, that he may really have lost his interest in it because of the French alliance, – all this is quite possible. Such considerations might have justified him in resigning his commission; or even, had he openly and frankly gone over to the enemy, much as we should have deplored such a step, some persons would always have been found to judge him charitably, and accord him the credit of acting upon principle. But the dark and crooked course which he did choose left open no alternative but that of unqualified condemnation. If we feel less of contempt and more of sorrow in the case of Arnold than in the case of such a weakling as Charles Lee, our verdict is not the less unmitigated.[38] Arnold’s fall was by far the more terrible, as he fell from a greater height, and into a depth than which none could be lower. It is only fair that we should recall his services to the cause of American independence, which were unquestionably greater than those of any other man in the Continental army except Washington and Greene. But it is part of the natural penalty that attaches to backsliding such as his, that when we hear the name of Benedict Arnold these are not the things which it suggests to our minds, but the name stands, and will always stand, as a symbol of unfaithfulness to trust.