полная версия

полная версияThe American Revolution

The astonished Gates called together his officers, and asked what was to be done. No one spoke for a few moments, until General Stevens exclaimed, “Well, gentlemen, is it not too late now to do anything but fight?” Kalb’s opinion was in favour of retreating to Clermont and taking a strong position there; but his advice had so often passed unheeded that he no longer urged it, and it was decided to open the battle by an attack on the British right.

KALB’S SWORD WORN AT CAMDEN

Battle of Camden, Aug. 16, 1780

The rising sun presently showed the two armies close together. Huge swamps, at a short distance from the road, on either side, covered both flanks of both armies. On the west side of the road the British left was commanded by Lord Rawdon, on the east side their right was led by Colonel James Webster, while Tarleton and his cavalry hovered a little in the rear. The American right wing, opposed to Rawdon, was commanded by Kalb, and consisted of the Delaware regiment and the second Maryland brigade in front, supported by the first Maryland brigade at some distance in the rear. The American left wing, opposed to Webster, consisted of the militia from Virginia and North Carolina, under Generals Stevens and Caswell. Such an arrangement of troops invited disaster. The battle was to begin with an attack on the British right, an attack upon disciplined soldiers; and the lead in this attack was entrusted to raw militia who had hardly ever been under fire, and did not even understand the use of the bayonet! This work should have been given to those splendid Maryland troops that had gone to help Sumter. The militia, skilled in woodcraft, should have been sent on that expedition, and the regulars should have been retained for the battle. The militia did not even know how to advance properly, but became tangled up; and while they were straightening their lines, Colonel Webster came down upon them in a furious charge. The shock of the British column was resistless. The Virginia militia threw down their guns and fled without firing a shot. The North Carolina militia did likewise, and within fifteen minutes the whole American left became a mob of struggling men, smitten with mortal panic, and huddling like sheep in their wild flight, while Tarleton’s cavalry gave chase and cut them down by scores. Leaving Tarleton to deal with them, Webster turned upon the first Maryland brigade, and slowly pushed it off the field, after an obstinate resistance. The second Maryland brigade, on the other hand, after twice repelling the assault of Lord Rawdon, broke through his left with a spirited bayonet charge, and remained victorious upon that part of the field, until the rest of the fight was ended; when being attacked in flank by Webster, these stalwart troops retreated westerly by a narrow road between swamp and hillside, and made their escape in good order. Long after the battle was lost in every other quarter, the gigantic form of Kalb, unhorsed and fighting on foot, was seen directing the movements of his brave Maryland and Delaware troops, till he fell dying from eleven wounds, Gates, caught in the throng of fugitives at the beginning of the action, was borne in headlong flight as far as Clermont, where, taking a fresh horse, he made the distance of nearly two hundred miles to Hillsborough in less than four days. The laurels of Saratoga had indeed changed into willows.

Total and ignominious defeat of GatesIt was the most disastrous defeat ever inflicted upon an American army, and ignominious withal, since it was incurred through a series of the grossest blunders. The Maryland troops lost half their number, the Delaware regiment was almost entirely destroyed, and all the rest of the army was dispersed. The number of killed and wounded has never been fully ascertained, but it can hardly have been less than 1,000, while more than 1,000 prisoners were taken, with seven pieces of artillery and 2,000 muskets. The British loss in killed and wounded was 324.

His campaign was a series of blundersThe reputation of General Gates never recovered from this sudden overthrow, and his swift flight to Hillsborough was made the theme of unsparing ridicule. Yet, if duly considered, that was the one part of his conduct for which he cannot fairly be blamed. The best of generals may be caught in a rush of panic-stricken fugitives and hurried off the battlefield: the flight of Frederick the Great at Mollwitz was even more ignominious than that of Gates at Camden. When once, moreover, the full extent of the disaster had become apparent, it was certainly desirable that Gates should reach Hillsborough as soon as possible, since it was the point from which the state organization of North Carolina was controlled, and accordingly the point at which a new army might soonest be collected. Gates’s flight was a singularly dramatic and appropriate end to his silly career, but our censure should be directed to the wretched generalship by which the catastrophe was prepared: to the wrong choice of roads, the fatal hesitation at the critical moment, the weakening of the army on the eve of battle; and, above all, to the rashness in fighting at all after the true state of affairs had become known. The campaign was an epitome of the kind of errors which Washington always avoided; and it admirably illustrated the inanity of John Adams’s toast, “A short and violent war,” against an enemy of superior strength.

Partisan operationsIf the 400 Maryland regulars who had been sent to help General Sumter had remained with the main army and been entrusted with the assault on the British right, the result of this battle would doubtless have been very different. It might not have been a victory, but it surely would not have been a rout. On the day before the battle, Sumter had attacked the British supply train on its way from Charleston, and captured all the stores, with more than 100 prisoners. But the defeat at Camden deprived this exploit of its value. Sumter retreated up the Wateree river to Fishing creek, but on the 18th Tarleton for once caught him napping, and routed him; taking 300 prisoners, setting free the captured British, and recovering all the booty. The same day witnessed an American success in another quarter. At Musgrove’s Mills, in the western part of the state, Colonel James Williams defeated a force of 500 British and Tories, killing and wounding nearly one third of their number. Two days later, Marion performed one of his characteristic exploits. A detachment of the British army was approaching Nelson’s Ferry, where the Santee river crosses the road from Camden to Charleston, when Marion, with a handful of men, suddenly darting upon these troops, captured 26 of their number, set free 150 Maryland prisoners whom they were taking down to the coast, and got away without losing a man.

Such deeds showed that the life of South Carolina was not quite extinct, but they could not go far toward relieving the gloom which overspread the country after the defeat of Camden. For a second time within three months the American army in the south had been swept out of existence. Gates could barely get together 1,000 men at Hillsborough, and Washington could not well spare any more from his already depleted force. To muster and train a fresh army of regulars would be slow and difficult work, and it was as certain as anything could be that Cornwallis would immediately proceed to attempt the conquest of North Carolina.

Weariness and depression of the peopleNever was the adage that the darkest time comes just before day more aptly illustrated than in the general aspect of American affairs during the summer and fall of 1780. The popular feeling had not so much the character of panic as in those “times which tried men’s souls,” when the broad Delaware river screened Washington’s fast dwindling army from destruction. It was not now a feeling of quick alarm so much as of utter weariness and depression. More than four years had passed since the Declaration of Independence, and although the enemy had as yet gained no firm foothold in the northern states except in the city of New York, it still seemed impossible to dislodge them from that point, while Cornwallis, flushed with victory, boasted that he would soon conquer all the country south of the Susquehanna. For the moment it began to look as if Lord George Germain’s policy of tiring the Americans out might prove successful, after all. The country was still without anything fit to be called a general government. After three years’ discussion, the Articles of Confederation, establishing a “league of friendship” between the thirteen states, had not yet been adopted. The Continental Congress had continued to decline in reputation and capacity. From this state of things, rather than from any real poverty of the country, there had ensued a general administrative paralysis, which went on increasing even after the war was ended, until it was brought to a close by the adoption of the Federal Constitution. It was not because the thirteen states were lacking in material resources or in patriotism that the conduct of the war languished as it did. The resources were sufficient, had there been any means of concentrating and utilizing them. The relations of the states to each other were not defined; and while there were thirteen powers which could plan and criticise, there was no single power which could act efficiently. Hence the energies of the people were frittered away.

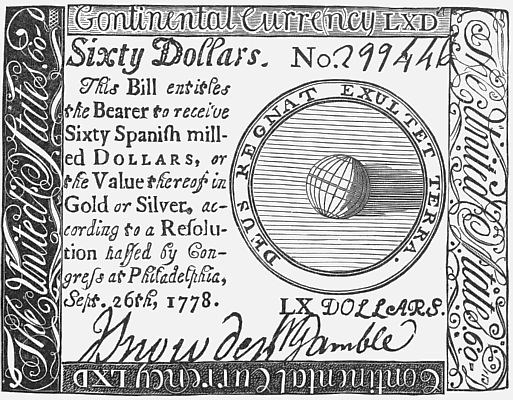

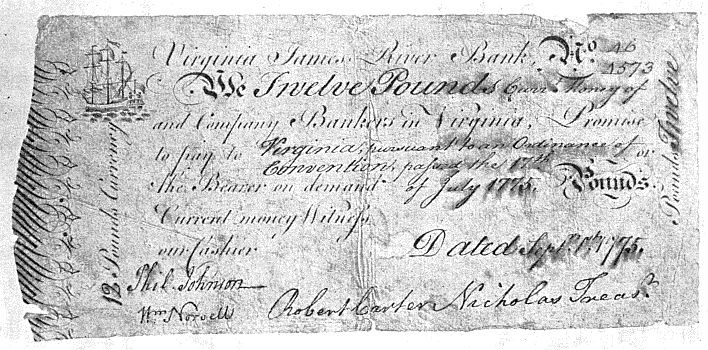

Evils wrought by the paper currencyThe disease was most plainly visible in those money matters which form the basis of all human activity. The Scondition of American finance in 1780 was simply horrible. The “greenback” delusion possessed people’s minds even more strongly then than in the days following our Civil War. Pelatiah Webster, the ablest political economist in America at that time, a thinker far in advance of his age, was almost alone in insisting upon taxation. The popular feeling was expressed by a delegate in Congress who asked, with unspeakable scorn, why he should vote to tax the people, when a Philadelphia printing-press could turn out money by the bushel.[31] But indeed, without an amendment, Congress had no power to lay any tax, save through requisitions upon the state governments. There seemed to be no alternative but to go on issuing this money, which many people glorified as the “safest possible currency,” because “nobody could take it out of the country.” As Webster truly said, the country had suffered more from this cause than from the arms of the enemy. “The people of the states at that time,” said he, “had been worried and fretted, disappointed and put out of humour, by so many tender acts, limitations of prices, and other compulsory methods to force value into paper money, and compel the circulation of it, and by so many vain funding schemes and declarations and promises, all which issued from Congress, but died under the most zealous efforts to put them into operation, that their patience was exhausted. These irritations and disappointments had so destroyed the courage and confidence of the people that they appeared heartless and almost stupid when their attention was called to any new proposal.” During the summer of 1780 this wretched “Continental” currency fell into contempt. As Washington said, it took a wagon-load of money to buy a wagon-load of provisions. At the end of the year 1778, the paper dollar was worth sixteen cents in the northern states and twelve cents in the south. Early in 1780 its value had fallen to two cents, and before the end of the year it took ten paper dollars to make a cent. In October, Indian corn sold wholesale in Boston for $150 a bushel, butter was $12 a pound, tea $90, sugar $10, beef $8, coffee $12, and a barrel of flour cost $1,575. Samuel Adams paid $2,000 for a hat and suit of clothes. The money soon ceased to circulate, debts could not be collected, and there was a general prostration of credit.

“Not worth a Continental”To say that a thing was “not worth a Continental” became the strongest possible expression of contempt. A barber in Philadelphia papered his shop with bills, and a dog was led up and down the streets, smeared with tar, with this unhappy “money” sticking all over him, – a sorry substitute for the golden-fleeced sheep of the old Norse legend. Save for the scanty pittance of gold which came in from the French alliance, from the little foreign commerce that was left, and from trade with the British army itself, the country was without any circulating medium. In making its requisitions upon the states, Congress resorted to a measure which reminds one of the barbaric ages of barter. Instead of asking for money, it requested the states to send in their “specific supplies” of beef and pork, flour and rice, salt and hay, tobacco and rum. The finances of what was so soon to become one of the richest of nations were thus managed on the principle whereby the meagre salaries of country clergymen in New England used to be eked out. It might have been called a continental system of “donation parties.”

VIRGINIA COLONIAL CURRENCY

Difficulty of keeping the army together

Under these circumstances, it became almost impossible to feed and clothe the army. The commissaries, without either money or credit, could do but little; and Washington, sorely against his will, was obliged to levy contributions on the country surrounding his camp. It was done as gently as possible. The county magistrates were called on for a specified quantity of flour and meat; the supplies brought in were duly appraised, and certificates were given in exchange for them by the commissaries. Such certificates were received at their nominal value in payment of taxes. But this measure, which simply introduced a new kind of paper money, served only to add to the general confusion. These difficulties, enhanced by the feeling that the war was dragged out to an interminable length, made it impossible to keep the army properly recruited.

When four months’ pay of a private soldier would not buy a single bushel of wheat for his family, and when he could not collect even this pittance, while most of the time he went barefoot and half-famished, it was not strange that he should sometimes feel mutinous. The desertions to the British lines at this time averaged more than a hundred a month. Ternay, the French admiral, wrote to Vergennes that the fate of North America was as yet very uncertain, and the Revolution by no means so far advanced as people in Europe supposed. The accumulated evils of the time had greatly increased the number of persons who, to save the remnant of their fortunes, were ready to see peace purchased at any price. In August, before he had heard of the disaster at Camden, Washington wrote to President Huntington, reminding him that the term of service of half the army would expire at the end of the year. “The shadow of an army that will remain,” said Washington, “will have every motive except mere patriotism to abandon the service, without the hope, which has hitherto supported them, of a change for the better. This is almost extinguished now, and certainly will not outlive the campaign unless it finds something more substantial to rest upon. To me it will appear miraculous if our affairs can maintain themselves much longer in their present train. If either the temper or the resources of the country will not admit of an alteration, we may expect soon to be reduced to the humiliating condition of seeing the cause of America in America upheld by foreign arms.”

The French allianceTo appreciate the full force of this, we must remember that, except in South Carolina, there had been no fighting worthy of mention during the year.

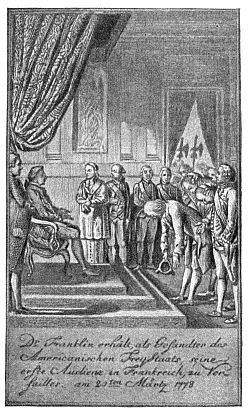

FRANKLIN BEFORE LOUIS XVI.

The southern campaign absorbed the energies of the British to such an extent that they did nothing whatever in the north but make an unsuccessful attempt at invading New Jersey in June. While this fact shows how severely the strength of England was taxed by the coalition that had been formed against her, it shows even more forcibly how the vitality of America had been sapped by causes that lay deeper down than the mere presence of war. It was, indeed, becoming painfully apparent that little was to be hoped save through the aid of France. The alliance had thus far achieved but little that was immediately obvious to the American people, but it had really been of enormous indirect benefit to us. Both in itself and in the European complications to which it had led, the action of France had very seriously crippled the efficient military power of England. It locked up and neutralized much British energy that would otherwise have been directed against the Americans. The French government had also furnished Congress with large sums of money. But as for any direct share in military enterprises on American soil or in American waters, France had as yet done almost nothing. An evil star had presided over both the joint expeditions for the recovery of Newport and Savannah, and no French army had yet been landed on our shores to cast in its lot with Washington’s brave Continentals in a great and decisive campaign.

It had long been clear that France could in no way more effectively further the interests which she shared with the United States than by sending a strong force of trained soldiers to act under Washington’s command. Nothing could be more obvious than the inference that such a general, once provided with an adequate force, might drive the British from New York, and thus deal a blow which would go far toward ending the war.

Lafayette’s visit to FranceThis had long been Washington’s most cherished scheme. In February, 1779, Lafayette had returned to France to visit his family, and to urge that aid of this sort might be granted. To chide him for his naughtiness in running away to America in defiance of the royal mandate, the king ordered him to be confined for a week at his father-in-law’s house in Paris. Then he received him quite graciously at court, while the queen begged him to “tell us good news of our dearly beloved Americans.” The good Lafayette, to whom, in the dreadful years that were to come, this dull king and his bright, unhappy queen were to look for compassionate protection, now ventured to give them some sensible words of advice. “The money that you spend on one of your old court balls,” he said, “would go far toward sending a serviceable army to America, and dealing England a blow where she would most feel it.” For several months he persisted in urging Vergennes to send over at least 12,000 men, with a good general, and to put them distinctly under Washington’s command, so that there might be no disastrous wrangling about precedence, and no repetition of such misunderstandings as had ruined the Newport campaign. When Estaing arrived at Paris, early in 1780, after his defeat at Savannah, he gave similar advice. The idea commended itself to Vergennes, and when, in April, 1780, Lafayette returned to the United States, he was authorized to inform Washington that France would soon send the desired reinforcement.

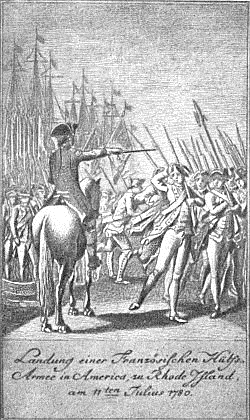

LANDING OF FRENCH TROOPS

Arrival of part of the French auxiliary force under Rochambeau

On the 10th of July, Admiral Ternay, with seven ships-of-the-line and three frigates, arrived at Newport, bringing with him a force of 6,000 men, commanded by a good general, Count Rochambeau. This was the first instalment of an army of which the remainder was to be sent as soon as adequate means of transport could be furnished. On the important question of military etiquette, Lafayette’s advice had been strictly heeded. Rochambeau was told to put himself under Washington’s command, and to consider his troops as part of the American army, while American officers were to take precedence of French officers of equal rank. This French army was excellent in discipline and equipment, and among its officers were some, such as the Duke de Lauzun-Biron and the Marquis de Chastellux, who had won high distinction. Rochambeau wrote to Vergennes that on his arrival he found the people of Rhode Island sad and discouraged. Everybody thought the country was going to the dogs. But when it was understood that this was but the advance guard of a considerable army and that France was this time in deadly earnest, their spirits rose, and the streets of Newport were noisy with hurrahs and brilliant with fireworks.

The hearts of the people, however, were still further to be sickened with hope deferred. Several British ships-of-the-line, arriving at New York, gave the enemy such a preponderance upon the water that Clinton resolved to take the offensive, and started down the Sound with 6,000 men to attack the French at Newport. Washington foiled this scheme by a sudden movement against New York, which obliged the British commander to fall back hastily for its defence; but the French fleet was nevertheless blockaded in Narragansett Bay by a powerful British squadron, and Rochambeau felt it necessary to keep his troops in Rhode Island to aid the admiral in case of such contingencies as might arise. The second instalment of the French army, on which their hopes had been built, never came, for a British fleet of thirty-two sail held it blockaded in the harbour of Brest.

General despondencyThe maritime supremacy of England thus continued to stand in the way of any great enterprise; and for a whole year the gallant army of Rochambeau was kept idle in Rhode Island, impatient and chafing under the restraint. The splendid work it was destined to perform under Washington’s leadership lay hidden in the darkness of the future, and for the moment the gloom which had overspread the country was only deepened. Three years had passed since the victory of Saratoga, but the vast consequences which were already flowing from that event had not yet disclosed their meaning. Looking only at the surface of things, it might well be asked – and many did ask – whether that great victory had really done anything more than to prolong a struggle which was essentially vain and hopeless. Such themes formed the burden of discourse at gentlemen’s dinner-tables and in the back parlours of country inns, where stout yeomen reviewed the situation of affairs through clouds of tobacco smoke; and never, perhaps, were the Tories more jubilant or the Whigs more crestfallen than at the close of this doleful summer.

It was just at this moment that the country was startled by the sudden disclosure of a scheme of blackest treason. For the proper explanation of this affair, a whole chapter will be required.

CHAPTER IV

BENEDICT ARNOLD

Arnold put in command of Philadelphia June 18, 1778To understand the proximate causes of Arnold’s treason, we must start from the summer of 1778, when Philadelphia was evacuated by the British. On that occasion, as General Arnold was incapacitated for active service by the wound he had received at Saratoga, Washington placed him in command of Philadelphia. This step brought Arnold into direct contact with Congress, toward which he bore a fierce grudge for the slights it had put upon him; and, moreover, the command was in itself a difficult one. The authority vested in the commandant was not clearly demarcated from that which belonged to the state government, so that occasions for dispute were sure to be forthcoming. While the British had held the city many of the inhabitants had given them active aid and encouragement, and there was now more or less property to be confiscated. By a resolve of Congress, all public stores belonging to the enemy were to be appropriated for the use of the army, and the commander-in-chief was directed to suspend the sale or transfer of goods until the general question of ownership should have been determined by a joint committee of Congress and of the Executive Council of Pennsylvania. It became Arnold’s duty to carry out this order, which not only wrought serious disturbance to business, but made the city a hornet’s nest of bickerings and complaints. The qualities needed for dealing successfully with such an affair as this were very different from the qualities which had distinguished Arnold in the field. The utmost delicacy of tact was required, and Arnold was blunt and self-willed, and deficient in tact. He was accordingly soon at loggerheads with the state government, and lost, besides, much of the personal popularity with which he started. Stories were whispered about to his discredit. It was charged against Arnold that the extravagance of his style of living was an offence against republican simplicity, and a scandal in view of the distressed condition of the country; that in order to obtain the means of meeting his heavy expenses he resorted to peculation and extortion; and that he showed too much favour to the Tories. These charges were doubtless not without some foundation. This era of paper money and failing credit was an era of ostentatious expenditure, not altogether unlike that which, in later days, preceded the financial break-down of 1873. People in the towns lived extravagantly, and in no other town was this more conspicuous than in Philadelphia; while perhaps no one in Philadelphia kept a finer stable of horses or gave more costly dinners than General Arnold. He ran in debt, and engaged in commercial speculations to remedy the evil; and, in view of the light afterward thrown upon his character, it is not unlikely that he may have sometimes availed himself of his high position to aid these speculations.