полная версия

полная версияThe American Revolution

While these things were going on, Washington had hoped, and Clinton had feared, that Estaing might presently reach New York in such force as to turn the scale there against the British. As soon as he learned that the French fleet was out of the way, Sir Henry Clinton proceeded to carry out a plan which he had long had in contemplation. A year had now elapsed since the beginning of active operations in the south, and, although the British arms had been crowned with success, it was desirable to strike a still heavier blow. The capture of the chief southern city was not only the next step in the plan of the campaign, but it was an object of especial desire to Sir Henry Clinton personally, for he had not forgotten the humiliating defeat at Fort Moultrie in 1776. He accordingly made things as snug as possible at the north, by finally withdrawing the garrisons from Rhode Island and the advanced posts on the Hudson. In this way, while leaving Knyphausen with a strong force in command of New York, he was enabled to embark 8,000 men on transports, under convoy of five ships-of-the-line; and on the day after Christmas, 1779, he set sail for Savannah, taking Lord Cornwallis with him.

The voyage was a rough one. Some of the transports foundered, and some were captured by American privateers. Yet when Clinton arrived in Georgia, and united his forces to those of Prevost, the total amounted to more than 10,000 men. He ventured, however, to weaken the garrison of New York still more, and sent back at once for 3,000 men under command of the young Lord Rawdon, of the famous family of Hastings, – better known in after-years as Earl of Moira and Marquis of Hastings, and destined, like Cornwallis, to serve with great distinction as governor-general of India. The event fully justified Clinton’s sagacity in taking this step. New York was quite safe for the present; for so urgent was the need for troops in South Carolina, and so great the difficulty of raising them, that Washington was obliged to detach from his army all the Virginia and North Carolina troops, and sent them down to aid General Lincoln. With his army thus weakened, it was out of the question for Washington to attack New York.

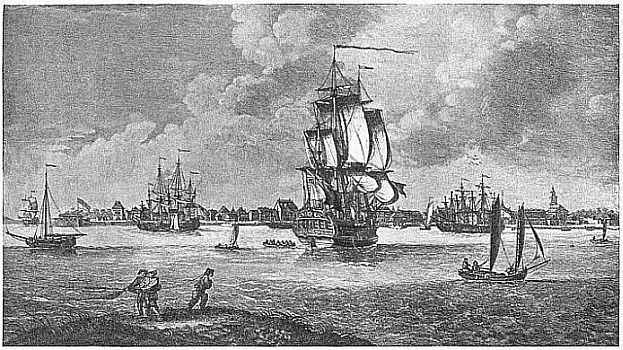

Lincoln, on the other hand, after his reinforcements arrived, had an army of 7,000 men with which to defend the threatened state of South Carolina. It was an inadequate force, and its commander, a thoroughly brave and estimable man, was far from possessing the rare sagacity which Washington displayed in baffling the schemes of the enemy. The government of South Carolina deemed the preservation of Charleston to be of the first importance, just as, in 1776, Congress had insisted upon the importance of keeping the city of New York. But we have seen how Washington, in that trying time, though he could not keep the city, never allowed himself to get his army into a position from which he could not withdraw it, and at last, through his sleepless vigilance, won all the honours of the campaign. In the defence of Charleston no such high sagacity was shown. Clinton advanced slowly overland, until on the 26th of February, 1780, he came in sight of the town. It had by that time become so apparent that his overwhelming superiority of force would enable him to encompass it on every side, that Lincoln should have evacuated the place without a moment’s delay; and such was Washington’s opinion as soon as he learned the facts. The loss of Charleston, however serious a blow, could in no case be so disastrous as the loss of the army. But Lincoln went on strengthening the fortifications, and gathering into the trap all the men and all the military resources he could find. For some weeks the connections with the country north of the Cooper river were kept open by two regiments of cavalry; but on the 14th of April these regiments were cut to pieces by Colonel Banastre Tarleton, the cavalry commander, who now first appeared on the scene upon which he was soon to become so famous. Five days later, the reinforcement under Lord Rawdon, arriving from New York, completed the investment of the doomed city. The ships entering the harbour did not attempt to batter down Fort Moultrie, but ran past it; and on the 6th of May this fortress, menaced by troops in the rear, surrendered.

Surrender of Charleston, May 12, 1780The British army now held Charleston engirdled with a cordon of works on every side, and were ready to begin an assault which, with the disparity of forces in the case, could have but one possible issue. On the 12th of May, to avoid a wanton waste of life, the city was surrendered, and Lincoln and his whole army became prisoners of war. The Continental troops, some 3,000 in number, were to be held as prisoners till regularly exchanged. The militia were allowed to return home on parole, and all the male citizens were reckoned as militia, and paroled likewise. The victorious Clinton at once sent expeditions to take possession of Camden and other strategic points in the interior of the state. One regiment of the Virginia line, under Colonel Buford, had not reached Charleston, and on hearing of the great catastrophe it retreated northward with all possible speed. But Tarleton gave chase as far as Waxhaws, near the North Carolina border, and there, overtaking Buford, cut his force to pieces, slaying 113 and capturing the rest. Not a vestige of an American army was left in all South Carolina.

A VIEW OF CHARLESTON BEFORE THE REVOLUTION

South Carolina overrun by the British

“We look on America as at our feet,” said Horace Walpole; and doubtless, after the capture of Fort Washington, this capture of Lincoln’s army at Charleston was the most considerable disaster which befell the American arms during the whole course of the war. It was of less critical importance than the affair of Fort Washington, as it occurred at what every one must admit to have been a less critical moment. The loss of Fort Washington, taken in connection with the misconduct of Charles Lee, came within a hair’s-breadth of wrecking the cause of American independence at the outset; and it put matters into so bad a shape that nothing short of Washington’s genius could have wrought victory out of them. The loss of South Carolina, in May, 1780, serious as it was, did not so obviously imperil the whole American cause. The blow did not come at quite so critical a time, or in quite so critical a place. The loss of South Carolina would not have dismembered the confederacy of states, and in course of time, with the American cause elsewhere successful, she might have been recovered. The blow was nevertheless very serious indeed, and, if all the consequences which Clinton contemplated had been achieved, it might have proved fatal. To crush a limb may sometimes be as dangerous as to stab the heart. For its temporary completeness, the overthrow may well have seemed greater than that of Fort Washington. The detachments which Clinton sent into the interior met with no resistance. Many of the inhabitants took the oath of allegiance to the Crown; others gave their parole not to serve against the British during the remainder of the war. Clinton issued a circular, inviting all well-disposed people to assemble and organize a loyal militia for the purpose of suppressing any future attempts at rebellion. All who should again venture to take up arms against the king were to be dealt with as traitors, and their estates were to be confiscated; but to all who should now return to their allegiance a free pardon was offered for past offences, except in the case of such people as had taken part in the hanging of Tories. Having struck this great blow, Sir Henry Clinton returned, in June, to New York, taking back with him the larger part of his force, but leaving Cornwallis with 5,000 men to maintain and extend the conquests already made.

MILES BREWTON HOUSE IN CHARLESTON

An injudicious proclamation

Just before starting, however, Sir Henry, in a too hopeful moment, issued another proclamation, which went far toward destroying the effect of his previous measures. This new proclamation required all the people of South Carolina to take an active part in reëstablishing the royal government, under penalty of being dealt with as rebels and traitors. At the same time, all paroles were discharged except in the case of prisoners captured in ordinary warfare, and thus everybody was compelled to declare himself as favourable or hostile to the cause of the invaders. The British commander could hardly have taken a more injudicious step. Under the first proclamation, many of the people were led to comply with the British demands because they wished to avoid fighting altogether; under the second, a neutral attitude became impossible, and these lovers of peace and quiet, when they found themselves constrained to take an active part on one side or the other, naturally preferred to help their friends rather than their enemies. Thus the country soon showed itself restless under British rule, and this feeling was strengthened by the cruelties which, after Clinton’s departure, Cornwallis found himself quite unable to prevent. Officers endowed with civil and military powers combined were sent about the country in all directions, to make full lists of the inhabitants for the purpose of enrolling a loyalist militia. In the course of these unwelcome circuits many affrays occurred, and instances were not rare in which people were murdered in cold blood.

Disorders in South CarolinaDebtors took occasion to accuse their creditors of want of loyalty, and the creditor was obliged to take the oath of allegiance before he could collect his dues. Many estates were confiscated, and the houses of such patriots as had sought refuge in the mountains were burned. Bands of armed men, whose aim was revenge or plunder, volunteered their services in preserving order, and, getting commissions, went about making disorder more hideous, and wreaking their evil will without let or hindrance. The loyalists, indeed, asserted that they behaved no worse than the Whigs when the latter got the upper hand, and in this there was much truth. Cornwallis, who was the most conscientious of men and very careful in his statements of fact, speaks, somewhat later, of “the shocking tortures and inhuman murders which are every day committed by the enemy, not only on those who have taken part with us, but on many who refuse to join them.” There can be no doubt that Whigs and Tories were alike guilty of cruelty and injustice. But on the present occasion all this disorder served to throw discredit on the British, as the party which controlled the country, and must be held responsible accordingly.

The strategic pointsOrganized resistance was impossible. The chief strategic points on the coast were Charleston, Beaufort, and Savannah; in the interior, Augusta was the gateway of Georgia, and the communications between this point and the wild mountains of North Carolina were dominated by a village known as “Ninety-Six,” because it was just that number of miles distant from Keowee, the principal town of the Cherokees. Eighty miles to the northeast of Ninety-Six lay the still more important post of Camden, in which centred all the principal inland roads by which South Carolina could be reached from the north. All these strategic points were held in force by the British, and save by help from without there seemed to be no hope of releasing the state from their iron grasp.

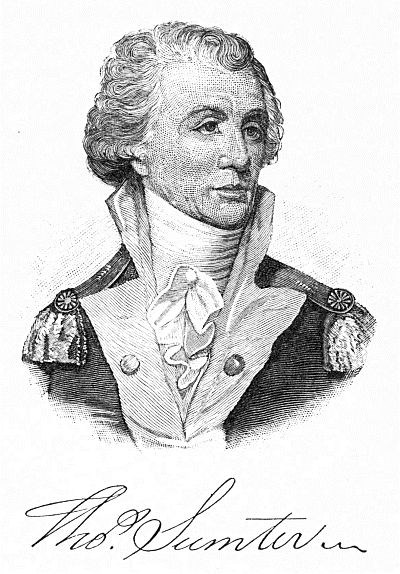

Partisan commandersAmong the patriotic Whigs, however, there were still some stout hearts that did not despair. Retiring to the dense woods, the tangled swamps, or the steep mountain defiles, these sagacious and resolute men kept up a romantic partisan warfare, full of midnight marches, sudden surprises, and desperate hand-to-hand combats. Foremost among these partisan commanders, for enterprise and skill, were James Williams, Andrew Pickens, Thomas Sumter, and Francis Marion.

FRANCIS MARION

Francis Marion

Of all the picturesque characters of our Revolutionary period, there is perhaps no one who, in the memory of the people, is so closely associated with romantic adventure as Francis Marion. He belonged to that gallant race of men of whose services France had been forever deprived when Louis XIV. revoked the edict of Nantes. His father had been a planter near Georgetown, on the coast, and the son, while following the same occupation, had been called off to the western frontier by the Cherokee war of 1759, in the course of which he had made himself an adept in woodland strategy. He was now forty-seven years old, a man of few words and modest demeanour, small in stature and slight in frame, delicately organized, but endowed with wonderful nervous energy and sleepless intelligence. Like a woman in quickness of sympathy, he was a knight in courtesy, truthfulness, and courage. The brightness of his fame was never sullied by an act of cruelty. “Never shall a house be burned by one of my people,” said he; “to distress poor women and children is what I detest.” To distress the enemy in legitimate warfare was, on the other hand, a business in which few partisan commanders have excelled him. For swiftness and secrecy he was unequalled, and the boldness of his exploits seemed almost incredible, when compared with the meagreness of his resources. His force sometimes consisted of less than twenty men, and seldom exceeded seventy.

To arm them, he was obliged to take the saws from sawmills and have them wrought into rude swords at the country forge, while pewter mugs and spoons were cast into bullets. With such equipment he would attack and overwhelm parties of more than two hundred Tories; or he would even swoop upon a column of British regulars on their march, throw them into disorder, set free their prisoners, slay and disarm a score or two, and plunge out of sight in the darkling forest as swiftly and mysteriously as he had come.

Second to Marion alone in this wild warfare was Thomas Sumter, a tall and powerful man, stern in countenance and haughty in demeanour. Born in Virginia in 1734, he was present at Braddock’s defeat in 1755, and after prolonged military service on the frontier found his way to South Carolina before the beginning of the Revolutionary War. He lived nearly a hundred years; sat in the Senate of the United States during the War of 1812, served as minister to Brazil, and witnessed the nullification acts of his adopted state under the stormy presidency of Jackson. During the summer of 1780, he kept up so brisk a guerrilla warfare in the upland regions north of Ninety-Six that Cornwallis called him “the greatest plague in the country.” “But for Sumter and Marion,” said the British commander, “South Carolina would be at peace.” The first advantage of any sort gained over the enemy since Clinton’s landing was the destruction of a company of dragoons by Sumter, on the 12th of July. Three weeks later, he made a desperate attack on the British at Rocky Mount, but was repulsed.

First appearance of Andrew JacksonOn the 6th of August, he surprised the enemy’s post at Hanging Rock, and destroyed a whole regiment. It was on this occasion that Andrew Jackson made his first appearance in history, an orphan boy of thirteen, staunch in the fight as any of his comrades.

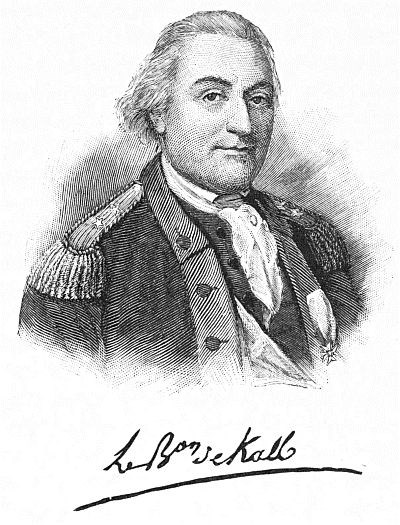

But South Carolina was too important to be left dependent upon the skill and bravery of its partisan commanders alone. Already, before the fall of Charleston, it had been felt that further reinforcements were needed there, and Washington had sent down some 2,000 Maryland and Delaware troops under Baron Kalb, an excellent officer.

Advance of KalbIt was a long march, and the 20th of June had arrived when Kalb halted at Hillsborough, in North Carolina, to rest his men and seek the coöperation of General Caswell, who commanded the militia of that state. By this time the news of the capture of Lincoln’s army had reached the north, and the emergency was felt to be a desperate one. Fresh calls for militia were made upon all the states south of Pennsylvania. That resources obtained with such difficulty should not be wasted, it was above all desirable that a competent general should be chosen to succeed the unfortunate Lincoln. The opinions of the commander-in-chief with reference to this matter were well known. Washington wished to have Greene appointed, as the ablest general in the army. But the glamour which enveloped the circumstances of the great victory at Saratoga was not yet dispelled. Since the downfall of the Conway cabal, Gates had never recovered the extraordinary place which he had held in public esteem at the beginning of 1778, but there were few as yet who seriously questioned the reputation he had so lightly won for generalship. Many people now called for Gates, who had for the moment retired from active service and was living on his plantation in Virginia, and the suggestion found favour with Congress.

Gates appointed to the chief command in the SouthOn the 13th of June Gates was appointed to the chief command of the southern department, and eagerly accepted the position. The good wishes of the people went with him. Richard Peters, secretary of the Board of War, wrote him a very cordial letter, saying, “Our affairs to the southward look blue: so they did when you took command before the Burgoynade. I can only now say, Go and do likewise– God bless you.” Charles Lee, who was then living in disgrace on his Virginia estate, sent a very different sort of greeting. Lee and Gates had always been friends, – linked together, perhaps, by pettiness of spirit and a common hatred for the commander-in-chief, whose virtues were a perpetual rebuke to them. But the cynical Lee knew his friend too well to share in the prevailing delusion as to his military capacity, and he bade him good-by with the ominous warning, “Take care that your northern laurels do not change to southern willows!”

With this word of ill omen, which doubtless he little heeded, the “hero of Saratoga” made his way to Hillsborough, where he arrived on the 19th of July, and relieved Kalb of the burden of anxiety that had been thrust upon him. Gates found things in a most deplorable state: lack of arms, lack of tents, lack of food, lack of medicines, and, above all, lack of money. The all-pervading neediness which in those days beset the American people, through their want of an efficient government, was never more thoroughly exemplified. It required a very different man from Gates to mend matters. Want of judgment and want of decision were faults which he had not outgrown, and all his movements were marked by weakness and rashness. He was adventurous where caution was needed, and timid when he should have been bold. The objective point of his campaign was the town of Camden. Once in possession of this important point, he could force the British from their other inland positions and throw them upon the defensive at Charleston. It was not likely that so great an object would be attained without a battle, but there was a choice of ways by which the strategic point might be approached. Two roads led from Hillsborough to Camden. The westerly route passed through Salisbury and Charlotte, in a long arc of a circle, coming down upon Camden from the northwest. The country through which it passed was fertile, and the inhabitants were mostly Scotch-Irish Whigs. By following this road, the danger of a sudden attack by the enemy would be slight, wholesome food would be obtained in abundance, and in case of defeat it afforded a safe line of retreat. The easterly route formed the chord of this long arc, passing from Hillsborough to Camden almost in a straight line 160 miles in length. It was 50 miles shorter than the other route, but it lay through a desolate region of pine barrens, where farmhouses and cultivated fields were very few and far between, and owned by Tories. This line of march was subject to flank attacks, it would yield no food for the army, and a retreat through it, on the morrow of an unsuccessful battle, would simply mean destruction. The only advantage of this route was its directness. The British forces were more or less scattered about the country. Lord Rawdon held Camden with a comparatively small force, and Gates was anxious to attack and overwhelm him before Cornwallis could come up from Charleston.

Gates chooses the wrong roadGates accordingly chose the shorter route, with all its disadvantages, in spite of the warnings of Kalb and other officers, and on the 27th of July he put his army in motion. On the 3d of August, having entered South Carolina and crossed the Pedee river, he was joined by Colonel Porterfield with a small force of Virginia regulars, which had been hovering on the border since the fall of Charleston. On the 7th he effected a junction with General Caswell and his North Carolina militia, and on the 10th his army, thus reinforced, reached Little Lynch’s Creek, about fifteen miles northeast of Camden, and confronted the greatly inferior force of Lord Rawdon. The two weeks’ march had been accomplished at the rate of about eleven miles a day, with no end of fatigue and suffering.

Distress of the troopsThe few lean kine slaughtered by the roadside had proved quite insufficient to feed the army, and for want of any better diet the half-starved men had eaten voraciously of unripe corn, green apples, and peaches. All were enfeebled, and many were dying of dysentery and cholera morbus, so that the American camp presented a truly distressing scene.

Gates loses the moment for strikingRawdon’s force stood across the road, blocking the way to Camden, and the chance was offered for Gates to strike the sudden blow for the sake of which he had chosen to come by this bad road. There was still, however, a choice of methods. The two roads, converging toward their point of intersection at Camden, were now very near together. Gates might either cross the creek in front, and trust to his superior numbers to overwhelm the enemy, or, by a forced march of ten miles to the right, he might turn Rawdon’s flank and gain Camden before him. A good general would have done either the one of these things or the other, and Kalb recommended the immediate attack. But now at the supreme moment Gates was as irresolute as he had been impatient when 160 miles away. He let the opportunity slip, waited two days where he was, and on the 13th marched slowly to the right and took up his position at Clermont, on the westerly road; thus abandoning the whole purpose for the sake of which he had refused to advance by that road in the first place. On the 14th he was joined by General Stevens with 700 Virginia militia; but on the same day Lord Cornwallis reached Camden with his regulars, and the golden moment for crushing the British in detachments was gone forever.

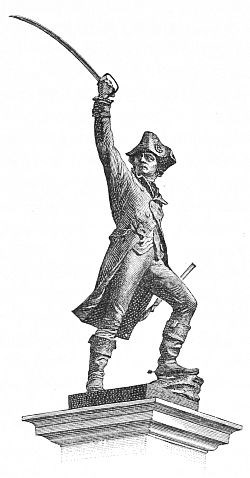

STATUE OF KALB AT ANNAPOLIS

The American army now numbered 3,052 men, of whom 1,400 were regulars, chiefly of the Maryland line. The rest were mostly raw militia. The united force under Cornwallis amounted to only 2,000 men, but they were all thoroughly trained soldiers. It was rash for the Americans to hazard an attack under such circumstances, especially in their forlorn condition, faint as they were with hunger and illness, and many of them hardly fit to march or take the field.

and weakens his army on the eve of battleBut, strange as it may seem, a day and a night passed by, and Gates had not yet learned that Cornwallis had arrived, but still supposed he had only Rawdon to deal with. It was no time for him to detach troops on distant expeditions, but on the 14th he sent 400 of his best Maryland regulars on a long march southward, to coöperate with Sumter in cutting off the enemy’s supplies on the road between Charleston and Camden. At ten o’clock on the night of the 15th, Gates moved his army down the road from Clermont to Camden, intending to surprise Lord Rawdon before daybreak. The distance was ten miles through the woods, by a rough road, hemmed in on either side, now by hills, and now by impassable swamps. At the very same hour, Cornwallis started up the road, with the similar purpose of surprising General Gates. A little before three in the morning, the British and American advance guards of light infantry encountered each other on the road, five miles north of Camden, and a brisk skirmish ensued, in which the Americans were routed and the gallant Colonel Porterfield was slain. Both armies, however, having failed in their scheme of surprising each other, lay on their arms and waited for daylight. Some prisoners who fell into the hands of the Americans now brought the news that the army opposed to them was commanded by Cornwallis himself, and they overstated its numbers at 3,000 men.