полная версия

полная версияThe American Revolution

42

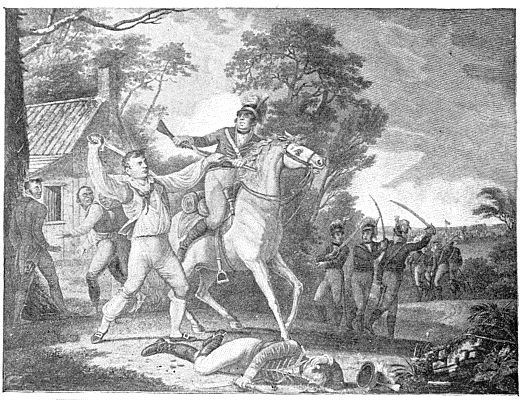

FRANCISCO’S SKIRMISH WITH TARLETON’S DRAGOONS

Just after the fight at Green Spring Tarleton made a raid through Amelia county and as far as Bedford, a hundred miles west of Petersburg. One of the incidents of this raid was made the subject of an engraving that was published in 1814 and soon became a familiar sight on the walls of public coffee-rooms and private parlours. Peter Francisco was a Portuguese waif, an indentured servant of Anthony Winston. As he grew to manhood his strength was such that he could lift upon his shoulder a cannon weighing half a ton, and his agility was equally remarkable. He entered the Continental service in 1777, in his seventeenth year, and fought at Brandywine, Germantown, Fort Mifflin, Monmouth, Stony Point, Camden, Cowpens, and Guilford, where he was wounded and left for dead. Plenty of life remained in him, however. On a July day, somewhere in Amelia county, alone and unarmed, he fell in with nine of Tarleton’s dragoons, one of whom demanded his shoe-buckles. “Take them off yourself,” said the quick-witted fellow-countryman of Magellan. As the man stooped to do the unbuckling, the young giant snatched away his sword and crushed in his skull with a single blow. Then quickly turning he slew two others, one of whom sat on horseback snapping a musket at him. At this moment Tarleton’s troop of 400 men appeared in the distance, whereupon the astute Francisco shouted in tremendous voice some words of command as if to an approaching party of his own. The six unhurt dragoons, who happened to be dismounted, were dazed with the sudden fury of Francisco’s attack, and at his deafening yell they fled in a panic, leaving their horses. These things all happened in the twinkling of an eye. Then Francisco vaulted into the saddle of one of the horses, seized the others by their bridles, and made off through the woods to Prince Edward Court House, where he sold all the horses save one noble charger which he named Tarleton and kept as his pet for many years. See Winston’s Peter Francisco, Soldier of the Revolution, Richmond, 1893.

The above incidents are epitomized in the picture without much regard to accuracy.

43

This slaughter, though sanctioned by European rules of warfare at that time, was not in accordance with usage in English America, either on the part of British or of Continentals. It was an instance of exceptional cruelty, and must be pronounced a serious blot upon the British record. See above, p. 116.

44

He died in London, June 14, 1801, and his burial in Brompton cemetery is mentioned in the Gentleman’s Magazine, lxxi. 580.

45

In using such a word as “gratitude” in this connection, one should not forget that the purposes of France, in helping us, were purely selfish. The feeling of the French government toward us was not really friendly, and its help was doled out with as niggardly a hand as possible. An instance of this was furnished immediately after the surrender of Yorktown, when Lafayette proposed to Grasse a combined movement upon Charleston in concert with Greene, but Grasse obstinately refused. See Harvard University Library, Sparks MSS. Such a movement promised success, though it might have entailed a battle with the British fleet. But Grasse was faithful to the policy of Vergennes, to help the Americans just enough, but not too much. This policy is discussed in my Critical Period of American History, chap, i., “Results of Yorktown,” in which the story is continued from the present chapter.