полная версия

полная версияThe American Revolution

It was in vain that Johnson and St. Leger exhorted and threatened the Indian allies. Already disaffected, they now began to desert by scores, while some, breaking open the camp chests, drank rum till they were drunk, and began to assault the soldiers. All night long the camp was a perfect Pandemonium. The riot extended to the Tories, and by noon of the next day St. Leger took to flight and his whole army was dispersed. All the tents, artillery, and stores fell into the hands of the Americans. The garrison, sallying forth, pursued St. Leger for a while, but the faithless Indians, enjoying his discomfiture, and willing to curry favour with the stronger party, kept up the chase nearly all the way to Oswego; laying ambushes every night, and diligently murdering the stragglers, until hardly a remnant of an army was left to embark with its crestfallen leader for Montreal.

Burgoyne’s dangerous situationThe news of this catastrophe reached Burgoyne before he had had time to recover from the news of the disaster at Bennington. Burgoyne’s situation was now becoming critical. Lincoln, with a strong force of militia, was hovering in his rear, while the main army before him was gaining in numbers day by day. Putnam had just sent up reinforcements from the Highlands; Washington had sent Morgan with 500 sharpshooters; and Arnold was hurrying back from Fort Stanwix. Not a word had come from Sir William Howe, and it daily grew more difficult to get provisions.

Schuyler superseded by Gates, Aug. 2Just at this time, when everything was in readiness for the final catastrophe, General Gates arrived from Philadelphia, to take command of the northern army, and reap the glory earned by other men. On the first day of August, before the first alarm occasioned by Burgoyne’s advance had subsided, Congress had yielded to the pressure of Schuyler’s enemies, and removed him from his command; and on the following day Gates was appointed to take his place. Congress was led to take this step through the belief that the personal hatred felt toward Schuyler by many of the New England people would prevent the enlisting of militia to support him. The events of the next fortnight showed that in this fear Congress was quite mistaken. There can now be no doubt that the appointment of the incompetent Gates was a serious blunder, which might have ruined the campaign, and did in the end occasion much trouble, both for Congress and for Washington. Schuyler received the unwelcome news with the noble unselfishness which always characterized him. At no time did he show more zeal and diligence than during his last week of command; and on turning over the army to General Gates he cordially offered his aid, whether by counsel or action, in whatever capacity his successor might see fit to suggest. But so far from accepting this offer, Gates treated him with contumely, and would not even invite him to attend his first council of war. Such silly behaviour called forth sharp criticisms from discerning people. “The new commander-in-chief of the northern department,” said Gouverneur Morris, “may, if he please, neglect to ask or disdain to receive advice; but those who know him will, I am sure, be convinced that he needs it.”

Position of the two armies, Aug. 19-Sept. 12When Gates thus took command of the northern army, it was stationed along the western bank of the Hudson, from Stillwater down to Halfmoon, at the mouth of the Mohawk, while Burgoyne’s troops were encamped along the eastern bank, some thirty miles higher up, from Fort Edward down to the Battenkill. For the next three weeks no movements were made on either side; and we must now leave the two armies confronting each other in these two positions, while we turn our attention southward, and see what Sir William Howe was doing, and how it happened that Burgoyne had as yet heard nothing from him.

CHAPTER VII

SARATOGA

OLD CITY HALL, WALL STREET, NEW YORK

Why Howe went to Chesapeake Bay

We have seen how, owing to the gross negligence of Lord George Germain, discretionary power had been left to Howe, while entirely taken away from Burgoyne. The latter had no choice but to move down the Hudson. The former was instructed to move up the Hudson, but at the same time was left free to depart from the strict letter of his instructions, should there be any manifest advantage in so doing. Nevertheless, the movement up the Hudson was so clearly prescribed by all sound military considerations that everybody wondered why Howe did not attempt it. Why he should have left his brother general in the lurch, and gone sailing off to Chesapeake Bay, was a mystery which no one was able to unravel, until some thirty years ago a document was discovered which has thrown much light upon the question.

Charles Lee in captivityHere there steps again upon the scene that miserable intriguer, whose presence in the American army had so nearly wrecked the fortunes of the patriot cause, and who now, in captivity, proceeded to act the part of a doubly-dyed traitor. A marplot and mischief-maker from beginning to end, Charles Lee never failed to work injury to whichever party his selfish vanity or craven fear inclined him for the moment to serve. We have seen how, on the day when he was captured and taken to the British camp, his first thought was for his personal safety, which he might well suppose to be in some jeopardy, since he had formerly held the rank of lieutenant-colonel in the British army. He was taken to New York and confined in the City Hall, where he was treated with ordinary courtesy; but there is no doubt that Sir William Howe looked upon him as a deserter, and was more than half inclined to hang him without ceremony. Fearing, however, as he said, that he might “fall into a law scrape,” should he act too hastily, Sir William wrote home for instructions, and in reply was directed by Lord George Germain to send his prisoner to England for trial. In pursuance of this order, Lee had already been carried on board ship, when a letter from Washington put a stop to these proceedings. The letter informed General Howe that Washington held five Hessian field-officers as hostages for Lee’s personal safety, and that all exchange of prisoners would be suspended until due assurance should be received that Lee was to be recognized as a prisoner of war. After reading this letter General Howe did not dare to send Lee to England for trial, for fear of possible evil consequences to the five Hessian officers, which might cause serious disaffection among the German troops. The king approved of this cautious behaviour, and so Lee was kept in New York, with his fate undecided, until it had become quite clear that neither arguments nor threats could avail one jot to shake Washington’s determination. When Lord George Germain had become convinced of this, he persuaded the reluctant king to yield the point; and Howe was accordingly instructed that Lee, although worthy of condign punishment, should be deemed a prisoner of war, and might be exchanged as such, whenever convenient.

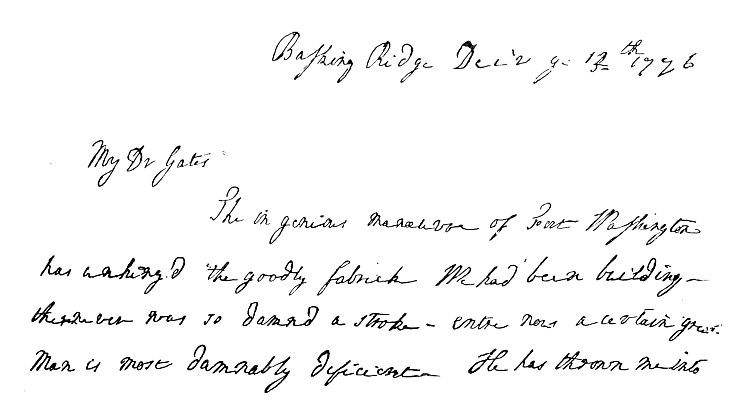

FACSIMILE OF FIRST LINES OF LEE’S LETTER TO GATES, DEC. 13, 1776

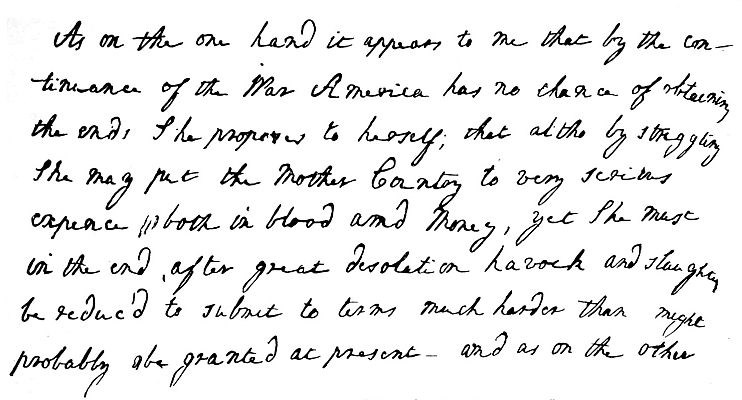

FACSIMILE OF FIRST LINES OF “MR. LEE’S PLAN, MARCH 29, 1777”

All this discussion necessitated the exchange of several letters between London and New York, so that a whole year elapsed before the question was settled. It was not until December 12, 1777, that Howe received these final instructions. But Lee had not been idle all this time while his fate was in suspense. Hardly had the key been turned upon him in his rooms at the City Hall when he began his intrigues. First, he assured Lord Howe and his brother that he had always opposed the declaration of independence,[14]and even now cherished hopes that, by a judiciously arranged interview with a committee from Congress, he might persuade the misguided people of America to return to their old allegiance.

Treason of Charles LeeLord Howe, who always kept one hand on the olive-branch, eagerly caught at the suggestion, and permitted Lee to send a letter to Congress, urging that a committee be sent to confer with him, as he had “important communications to make.” Could such a conference be brought about, he thought, his zeal for effecting a reconciliation would interest the Howes in his favour, and might save his precious neck. Congress, however, flatly refused to listen to the proposal, and then the wretch, without further ado, went over to the enemy, and began to counsel with the British commanders how they might best subdue the Americans in the summer campaign. He went so far as to write out for the brothers Howe a plan of operations, giving them the advantage of what was supposed to be his intimate knowledge of the conditions of the case. This document the Howes did not care to show after the disastrous event of the campaign, and it remained hidden for eighty years, until it was found among the domestic archives of the Strachey family, at Sutton Court, in Somerset. The first Sir Henry Strachey was secretary to the Howes from 1775 to 1778. The document is in Lee’s well-known handwriting, and is indorsed by Strachey as “Mr. Lee’s plan, March 29, 1777.” In this document Lee maintains that if the state of Maryland could be overawed, and the people of Virginia prevented from sending aid to Pennsylvania, then Philadelphia might be taken and held, and the operations of the “rebel government” paralyzed. The Tory party was known to be strong in Pennsylvania, and the circumstances under which Maryland had declared for independence, last of all the colonies save New York, were such as to make it seem probable that there also the loyalist feeling was very powerful. Lee did not hesitate to assert, as of his own personal knowledge, that the people of Maryland and Pennsylvania were nearly all loyalists, who only awaited the arrival of a British army in order to declare themselves. He therefore recommended that 14,000 men should drive Washington out of New Jersey and capture Philadelphia, while the remainder of Howe’s army, 4,000 in number, should go around by sea to Chesapeake Bay, and occupy Alexandria and Annapolis. From these points, if Lord Howe were to issue a proclamation of amnesty, the pacification of the “central colonies” might be effected in less than two months; and so confident of all this did the writer feel that he declared himself ready to “stake his life upon the issue,” a remark which betrays, perhaps, what was uppermost in his mind throughout the whole proceeding. At the same time, he argued that offensive operations toward the north could not “answer any sort of purpose,” since the northern provinces “are at present neither the seat of government, strength, nor politics; and the apprehensions from General Carleton’s army will, I am confident, keep the New Englanders at home, or at least confine ’em to the east side the [Hudson] river.”

Folly of moving upon Philadelphia, as the “rebel capital”It will be observed that this plan of Lee’s was similar to that of Lord George Germain, in so far as it aimed at thrusting the British power like a wedge into the centre of the confederacy, and thus cutting asunder New England and Virginia, the two chief centres of the rebellion. But instead of aiming his blow at the Hudson river, Lee aims it at Philadelphia, as the “rebel capital;” and his reason for doing this shows how little he understood American affairs, and how strictly he viewed them in the light of his military experience in Europe. In European warfare it is customary to strike at the enemy’s capital city, in order to get control of his whole system of administration; but that the possession of an enemy’s capital is not always decisive the wars of Napoleon have most abundantly proved. The battles of Austerlitz in 1805 and Wagram in 1809 were fought by Napoleon after he had entered Vienna; it was not his acquisition of Berlin in 1806, but his victory at Friedland in the following summer, that completed the overthrow of Prussia; and where he had to contend against a strong and united national feeling, as in Spain and Russia, the possession of the capital did not help him in the least. Nevertheless, in European countries, where the systems of administration are highly centralized, it is usually advisable to move upon the enemy’s capital. But to apply such a principle to Philadelphia in 1777 was the height of absurdity. Philadelphia had been selected for the meetings of the Continental Congress because of its geographical position. It was the most centrally situated of our large towns, but it was in no sense the centre of a vast administrative machinery. If taken by an enemy, it was only necessary for Congress to move to any other town, and everything would go on as before. As it was not an administrative, so neither was it a military centre. It commanded no great system of interior highways, and it was comparatively difficult to protect by the fleet. It might be argued, on the other hand, that because Philadelphia was the largest town in the United States, and possessed of a certain preëminence as the seat of Congress, the acquisition of it by the invaders would give them a certain moral advantage. It would help the Tory party, and discourage the patriots. Such a gain, however, would be trifling compared with the loss which might come from Howe’s failure to coöperate with Burgoyne; and so the event most signally proved.

Effect of Lee’s adviceJust how far the Howes were persuaded by Lee’s arguments must be a matter of inference. The course which they ultimately pursued, in close conformity with the suggestions of this remarkable document, was so disastrous to the British cause that the author might almost seem to have been intentionally luring them off on a false scent. One would gladly take so charitable a view of the matter, were it not both inconsistent with what we have already seen of Lee, and utterly negatived by his scandalous behaviour the following year, after his restoration to his command in the American army. We cannot doubt that Lee gave his advice in sober earnest. That considerable weight was attached to it is shown by a secret letter from Sir William Howe to Lord George Germain, dated the 2d of April or four days after the date of Lee’s extraordinary document. In this letter, Howe, intimates for the first time that he has an expedition in mind which may modify the scheme for a joint campaign with the northern army along the line of the Hudson. To this suggestion Lord George replied on the 18th of May: “I trust that whatever you may meditate will be executed in time for you to coöperate with the army to proceed from Canada.” It was a few days after this that Lord George, perhaps feeling a little uneasy about the matter, wrote that imperative order which lay in its pigeon-hole in London until all the damage was done.

Washington’s masterly campaign in New Jersey, June, 1777With these data at our command, it becomes easy to comprehend General Howe’s movements during the spring and summer. His first intention was to push across New Jersey with the great body of his army, and occupy Philadelphia; and since he had twice as many men as Washington, he might hope to do this in time to get back to the Hudson as soon as he was likely to be needed there. He began his march on the 12th of June, five days before Burgoyne’s flotilla started southward on Lake Champlain. The enterprise did not seem hazardous, but Howe was completely foiled by Washington’s superior strategy. Before the British commander had fairly begun to move, Washington, from various symptoms, divined his purpose, and coming down from his lair at Morristown, planted himself on the heights of Middlebrook, within ten miles of New Brunswick, close upon the flank of Howe’s line of march. Such a position, occupied by 8,000 men under such a general, was something which Howe could not pass by without sacrificing his communications and thus incurring destruction. But the position was so strong that to try to storm it would be to invite defeat. It remained to be seen what could be done by manœuvring. The British army of 18,000 men was concentrated at New Brunswick, with plenty of boats for crossing the Delaware river, when that obstacle should be reached. But the really insuperable obstacle was close at hand. A campaign of eighteen days ensued, consisting of wily marches and counter-marches, the result of which showed that Washington’s advantage of position could not be wrested from him. Howe could neither get by him nor outwit him, and was too prudent to attack him; and accordingly, on the last day of June, he abandoned his first plan, and evacuated New Jersey, taking his whole army over to Staten Island.

Uncertainty as to Howe’s next movementsThis campaign has attracted far less attention than it deserves, mainly, no doubt, because it contained no battles or other striking incidents. It was purely a series of strategic devices. But in point of military skill it was, perhaps, as remarkable as anything that Washington ever did, and it certainly occupies a cardinal position in the history of the overthrow of Burgoyne. For if Howe had been able to take Philadelphia early in the summer, it is difficult to see what could have prevented him from returning and ascending the Hudson, in accordance with the plan of the ministry. Now the month of June was gone, and Burgoyne was approaching Ticonderoga. Howe ought to have held himself in readiness to aid him, but he could not seem to get Philadelphia, the “rebel capital,” out of his mind. His next plan coincided remarkably with the other half of Lee’s scheme. He decided to go around to Philadelphia by sea, but he was slow in starting, and seems to have paused for a moment to watch the course of events at the north. He began early in July to put his men on board ship, but confided his plans to no one but Cornwallis and Grant; and his own army, as well as the Americans, believed that this show of going to sea was only a feint to disguise his real intention. Every one supposed that he would go up the Hudson. As soon as New Jersey was evacuated Washington moved back to Morristown, and threw his advance, under Sullivan, as far north as Pompton, so as to be ready to coöperate with Putnam in the Highlands, at a moment’s notice. As soon as it became known that Ticonderoga had fallen, Washington, supposing that his adversary would do what a good general ought to do, advanced into the Ramapo Clove, a rugged defile in the Highlands, near Haverstraw, and actually sent the divisions of Sullivan and Stirling across the river to Peekskill.

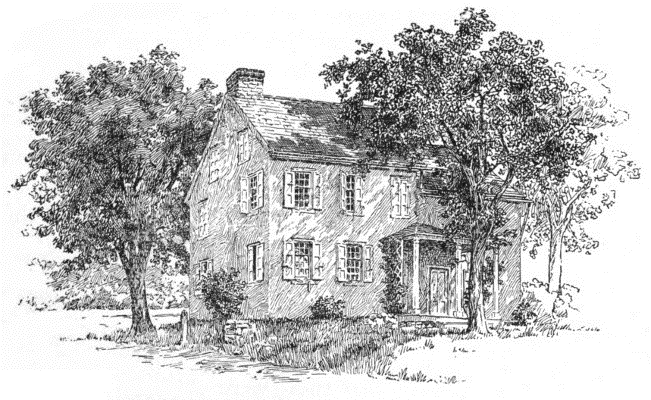

WASHINGTON’S HEADQUARTERS AT CHADD’S FORD

Howe’s letter to Burgoyne

All this while Howe kept moving some of his ships, now up the Hudson, now into the Sound, now off from Sandy Hook, so that people might doubt whether his destination were the Highlands, or Boston, or Philadelphia. Probably his own mind was not fully made up until after the news from Ticonderoga. Then, amid the general exultation, he seems to have concluded that Burgoyne would be able to take care of himself, at least with such coöperation as he might get from Sir Henry Clinton. In this mood he wrote to Burgoyne as follows: “I have … heard from the rebel army of your being in possession of Ticonderoga, which is a great event, carried without loss… Washington is waiting our motions here, and has detached Sullivan with about 2,500 men, as I learn, to Albany. My intention is for Pennsylvania, where I expect to meet Washington; but if he goes to the northward, contrary to my expectations, and you can keep him at bay, be assured I shall soon be after him to relieve you. After your arrival at Albany, the movements of the enemy will guide yours; but my wishes are that the enemy be drove [sic] out of this province before any operation takes place in Connecticut. Sir Henry Clinton remains in the command here, and will act as occurrences may direct. Putnam is in the Highlands with about 4,000 men. Success be ever with you.” This letter, which was written on very narrow strips of thin paper, and conveyed in a quill, did not reach Burgoyne till the middle of September, when things wore a very different aspect from that which they wore in the middle of July. Nothing could better illustrate the rash, overconfident spirit in which Howe proceeded to carry out his southern scheme. A few days afterward he put to sea with the fleet of 228 sail, carrying an army of 18,000 men, while 7,000 were left in New York, under Sir Henry Clinton, to garrison the city and act according to circumstances. Just before sailing Howe wrote a letter to Burgoyne, stating that the destination of his fleet was Boston, and he artfully contrived that this letter should fall into Washington’s hands. But Washington was a difficult person to hoodwink. On reading the letter he rightly inferred that Howe had gone southward. Accordingly, recalling Sullivan and Stirling to the west side of the Hudson, he set out for the Delaware, but proceeded very cautiously, lest Howe should suddenly retrace his course, and dart up the Hudson. To guard against such an emergency, he let Sullivan advance no farther than Morristown, and kept everything in readiness for an instant counter-march. In a letter of July 30th he writes, “Howe’s in a manner abandoning Burgoyne is so unaccountable a matter that, till I am fully assured of it, I cannot help casting my eyes continually behind me.” Next day, learning that the fleet had arrived at the Capes of Delaware, he advanced to Germantown; but on the day after, when he heard that the fleet had put out to sea again, he suspected that the whole movement had been a feint.

Comments of Washington and GreeneHe believed that Howe would at once return to the Hudson, and immediately ordered Sullivan to counter-march, while he held himself ready to follow at a moment’s notice. His best generals entertained the same opinion. “I cannot persuade myself,” said Greene, “that General Burgoyne would dare to push with such rapidity towards Albany if he did not expect support from General Howe.” A similar view of the military exigencies of the case was taken by the British officers, who, almost to a man, disapproved of the southward movement. They knew as well as Greene that, however fine a city Philadelphia might be, it was “an object of far less military importance than the Hudson river.”

Howe’s alleged reason trumped up and worthlessNo wonder that the American generals were wide of the mark in their conjectures, for the folly of Howe’s movements after reaching the mouth of the Delaware was quite beyond credence, and would be inexplicable to-day except as the result of the wild advice of the marplot Lee. Howe alleged as his reason for turning away from the Delaware, that there were obstructions in the river and forts to pass, and accordingly he thought it best to go around by way of Chesapeake Bay, and land his army at Elkton. Now he might easily have gone a little way up the Delaware river without encountering any obstructions whatever, and landed his troops at a point only thirteen miles east of Elkton. Instead of attempting this, he wasted twenty-four days in a voyage of four hundred miles, mostly against headwinds, in order to reach the same point! No sensible antagonist could be expected to understand such eccentric behaviour. No wonder that, after it had become clear that the fleet had gone southward, Washington should have supposed an attack on Charleston to be intended. A council of war on the 21st decided that this must be the case, and since an overland march of seven hundred miles could not be accomplished in time to prevent such an attack, it was decided to go back to New York, and operate against Sir Henry Clinton. But before this decision was acted on Howe appeared at the head of Chesapeake Bay, where he landed his forces at Elkton. It was now the 25th of August, – nine days after the battle of Bennington and three days after the flight of St. Leger.

Burgoyne’s fate practically decidedSince entering Chesapeake Bay, Howe had received Lord George Germain’s letter of May 18th, telling him that whatever he had to do ought to be done in time for him to coöperate with Burgoyne. Now Burgoyne’s situation had become dangerous, and here was Howe at Elkton, fifty miles southwest of Philadelphia, with Washington’s army in front of him, and more than three hundred miles away from Burgoyne!