полная версия

полная версияThe American Revolution

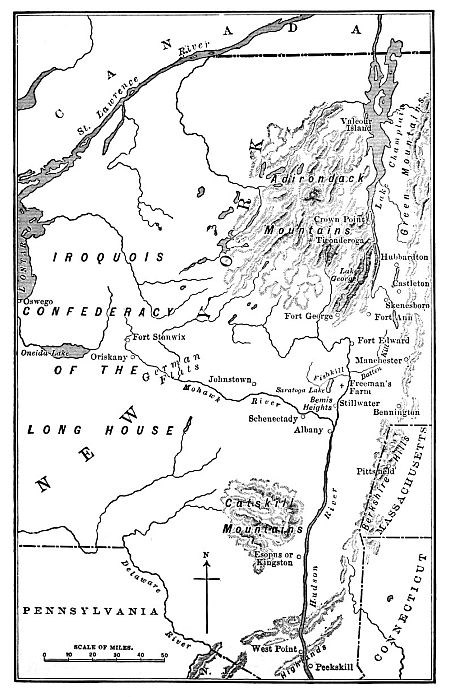

BURGOYNE’S INVASION OF NEW YORK, JULY-OCTOBER, 1777

Germain’s fatal error

It does not appear, therefore, that there were any advantages to be gained by Burgoyne’s advance from the north which can be regarded as commensurate with the risk which he incurred. To have transferred the northern army from the St. Lawrence to the Hudson by sea would have been far easier and safer than to send it through a hundred miles of wilderness in northern New York; and whatever it could have effected in the interior of the state could have been done as well in the former case as in the latter. But these considerations do not seem to have occurred to Lord George Germain. In the wars with the French, the invading armies from Canada had always come by way of Lake Champlain, so that this route was accepted without question, as if consecrated by long usage. Through a similar association of ideas an exaggerated importance was attached to the possession of Ticonderoga. The risks of the enterprise, moreover, were greatly underestimated. In imagining that the routes of Burgoyne and St. Leger would lie through a friendly country, the ministry fatally misconceived the whole case. There was, indeed, a powerful Tory party in the country, just as in the days of Robert Bruce there was an English party in Scotland, just as in the days of Miltiades there was a Persian party in Attika. But no one has ever doubted that the victors at Marathon and at Bannockburn went forth with a hearty godspeed from their fellow-countrymen; and the obstinate resistance encountered by St. Leger, within a short distance of Johnson’s Tory stronghold, is an eloquent commentary upon the error of the ministry in their estimate of the actual significance of the loyalist element on the New York frontier.

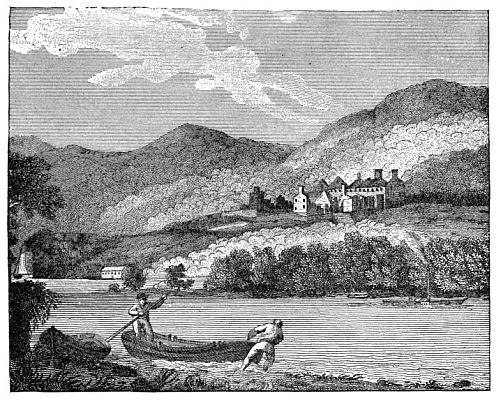

RUINS OF TICONDEROGA IN 1818

Too many unknown quantities

It thus appears that in the plan of a triple invasion upon converging lines the ministry were dealing with too many unknown quantities. They were running a prodigious risk for the sake of an advantage which in itself was extremely open to question; for should it turn out that the strength of the Tory party was not sufficiently great to make the junction of the three armies at Albany at once equivalent to the complete conquest of the state, then the end for which the campaign was undertaken could not be secured without supplementary campaigns. Neither a successful march up and down the Hudson river nor the erection of a chain of British fortresses on that river could effectually cut off the southern communications of New England, unless all military resistance were finally crushed in the state of New York. The surest course for the British, therefore, would have been to concentrate all their available force at the mouth of the Hudson, and continue to make the destruction of Washington’s army the chief object of their exertions. In view of the subtle genius which he had shown during the last campaign, that would have been an arduous task; but, as events showed, they had to deal with his genius all the same on the plan which they adopted, and at a great disadvantage.

Danger from New England ignoredAnother point which the ministry overlooked was the effect of Burgoyne’s advance upon the people of New England. They could reasonably count upon alarming the yeomanry of New Hampshire and Massachusetts by a bold stroke upon the Hudson, but they failed to see that this alarm would naturally bring about a rising that would be very dangerous to the British cause. Difficult as it was at that time to keep the Continental army properly recruited, it was not at all difficult to arouse the yeomanry in the presence of an immediate danger. In the western parts of New England there were scarcely any Tories to complicate the matter; and the flank movement by the New England militia became one of the most formidable features in the case.

The dispatch that was never sentBut whatever may be thought of the merits of Lord George’s plan, there can be no doubt that its success was absolutely dependent upon the harmonious coöperation of all the forces involved in it. The ascent of the Hudson by Sir William Howe, with the main army, was as essential a part of the scheme as the descent of Burgoyne from the north; and as the two commanders could not easily communicate with each other, it was necessary that both should be strictly bound by their instructions. At this point a fatal blunder was made. Burgoyne was expressly directed to follow the prescribed line down the Hudson, whatever might happen, until he should effect his junction with the main army. On the other hand, no such unconditional orders were received by Howe. He understood the plan of campaign, and knew that he was expected to ascend the river in force; but he was left with the usual discretionary power, and we shall presently see what an imprudent use he made of it. The reasons for this inconsistency on the part of the ministry were for a long time unintelligible; but a memorandum of Lord Shelburne, lately brought to light by Lord Edmund Fitzmaurice, has solved the mystery. It seems that a dispatch, containing positive and explicit orders for Howe to ascend the Hudson, was duly drafted, and, with many other papers, awaited the minister’s signature. Lord George Germain, being on his way to the country, called at his office to sign the dispatches; but when he came to the letter addressed to General Howe, he found it had not been “fair copied.” Lord George, like the old gentleman who killed himself in defence of the great principle that crumpets are wholesome, never would be put out of his way by anything. Unwilling to lose his holiday, he hurried off to the green meadows of Kent, intending to sign the letter on his return. But when he came back the matter had slipped from his mind. The document on which hung the fortunes of an army, and perhaps of a nation, got thrust unsigned into a pigeon-hole, where it was duly discovered some time after the disaster at Saratoga had become part of history.

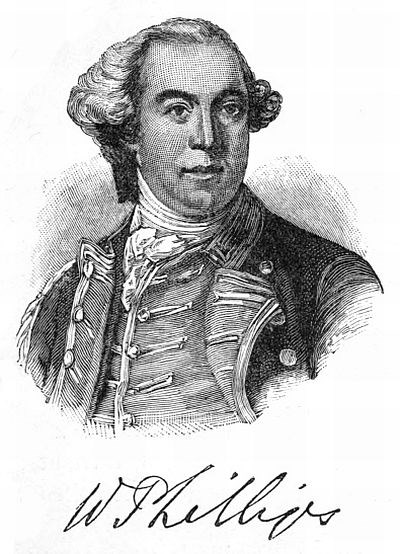

Happy in his ignorance of the risks he was assuming, Burgoyne took the field about the 1st of June, with an army of 7,902 men, of whom 4,135 were British regulars. His German troops from Brunswick, 3,116 in number, were commanded by Baron Riedesel, an able general, whose accomplished wife has left us such a picturesque and charming description of the scenes of this adventurous campaign. Of Canadian militia there were 148, and of Indians 503. The regular troops, both German and English, were superbly trained and equipped, and their officers were selected with especial care. Generals Phillips and Fraser were regarded as among the best officers in the British service.

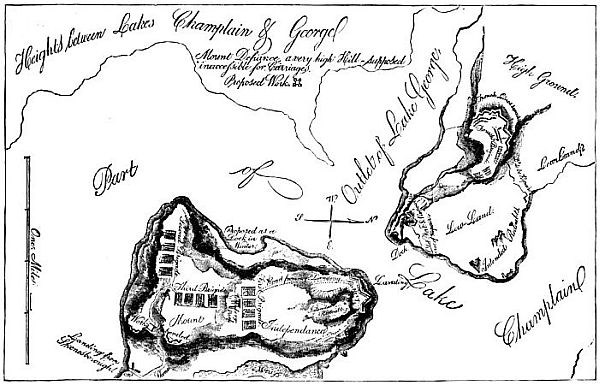

Burgoyne advances upon TiconderogaOn the second anniversary of Bunker Hill this army began crossing the lake to Crown Point; and on the 1st of July it appeared before Ticonderoga, where St. Clair was posted with a garrison of 3,000 men. Since its capture by Allen, the fortress had been carefully strengthened, until it was now believed to be impregnable. But while no end of time and expense had been devoted to the fortifications, a neighbouring point which commands the whole position had been strangely neglected. A little less than a mile south of Ticonderoga, the narrow mountain ridge between the two lakes ends abruptly in a bold crag, which rises 600 feet sheer over the blue water.

Phillips seizes Mount DefiancePractised eyes in the American fort had already seen that a hostile battery Phillips planted on this eminence would render their stronghold untenable; but it was not believed that siege-guns could be dragged up the steep ascent, and so, in spite of due warning, the crag had not been secured when the British army arrived. General Phillips at once saw the value of the position, and, approaching it by a defile that was screened from the view of the fort, worked night and day in breaking out a pathway and dragging up cannon. “Where a goat can go, a man may go; and where a man can go, he can haul up a gun,” argued the gallant general. Great was the astonishment of the garrison when, on the morning of July 5th, they saw red coats swarming on the hill, which the British, rejoicing in their exploit, now named Mount Defiance. There were not only red coats there, but brass cannon, which by the next day would be ready for work. Ticonderoga had become a trap, from which the garrison could not escape too quickly.

St. Clair abandons Ticonderoga, July 5, 1777A council of war was held, and under cover of night St. Clair took his little army across the lake and retreated upon Castleton in the Green Mountains. Such guns and stores as could be saved, with the women and wounded men, were embarked in 200 boats, and sent, under a strong escort, to the head of the lake, whence they continued their retreat to Fort Edward on the Hudson. About three o’clock in the morning a house accidentally took fire, and in the glare of the flames the British sentinels caught a glimpse of the American rear-guard just as it was vanishing in the sombre depths of the forest. Alarm guns were fired, and in less than an hour the British flag was hoisted over the empty fortress, while General Fraser, with 900 men, had started in hot pursuit of the retreating Americans. Riedesel was soon sent to support him, while Burgoyne, leaving nearly 1,000 men to garrison the fort, started up the lake with the main body of the army.

Battle of Hubbardton, July 7On the morning of the 7th, General Fraser overtook the American rear-guard of 1,000 men, under Colonels Warner and Francis, at the village of Hubbardton, about six miles behind the main army. A fierce fight ensued, in which Fraser was worsted, and had begun to fall back, with the loss of one fifth of his men, when Riedesel came up with his Germans, and the Americans were put to flight, leaving one third of their number killed or wounded. This obstinate resistance at Hubbardton served to check the pursuit, and five days later St. Clair succeeded, without further loss, in reaching Fort Edward, where he joined the main army under Schuyler.

TRUMBULL’S PLAN OF TICONDEROGA AND MOUNT DEFIANCE

One swallow does not make a summer

Up to this moment, considering the amount of work done and the extent of country traversed, the loss of the British had been very small. They began to speak contemptuously of their antagonists, and the officers amused themselves by laying wagers as to the precise number of days it would take them to reach Albany. In commenting on the failure to occupy Mount Defiance, Burgoyne made a general statement on the strength of a single instance, – which is the besetting sin of human reasoning. “It convinces me,” said he, “that the Americans have no men of military science.” Yet General Howe at Boston, in neglecting to occupy Dorchester Heights, had made just the same blunder, and with less excuse; for no one had ever doubted that batteries might be placed there by somebody.

The king’s gleeIn England the fall of Ticonderoga was greeted with exultation, as the death-blow to the American cause. Horace Walpole tells how the king rushed into the queen’s apartment, clapping his hands and shouting, “I have beat them! I have beat all the Americans!” People began to discuss the best method of reëstablishing the royal governments in the “colonies.” In America there was general consternation. St. Clair was greeted with a storm of abuse.

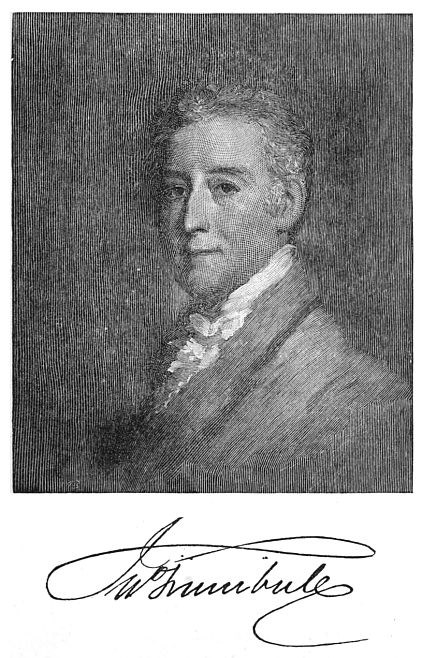

Wrath of John AdamsJohn Adams, then president of the Board of War, wrote, in the first white heat of indignation, “We shall never be able to defend a post till we shoot a general!” Schuyler, too, as commander of the department, was ignorantly and wildly blamed, and his political enemies seized upon the occasion to circulate fresh stories to his discredit. A court-martial in the following year vindicated St. Clair’s prudence in giving up an untenable position and saving his army from capture. The verdict was just, but there is no doubt that the failure to fortify Mount Defiance was a grave error of judgment, for which the historian may fairly apportion the blame between St. Clair and Gates. It was Gates who had been in command of Ticonderoga in the autumn of 1776, when an attack by Carleton was expected, and his attention had been called to this weak point by Colonel Trumbull, whom he laughed to scorn. Gates had again been in command from March to June. St. Clair had taken command about three weeks before Burgoyne’s approach; he had seriously considered the question of fortifying Mount Defiance, but had not been sufficiently prompt.

Gates chiefly to blameIn no case could any blame attach to Schuyler. Gates was more at fault than any one else, but he did not happen to be at hand when the catastrophe occurred, and accordingly people did not associate him with it. On the contrary, amid the general wrath, the loss of the northern citadel was alleged as a reason for superseding Schuyler by Gates; for if he had been there, it was thought that the disaster would have been prevented.

The irony of events, however, alike ignoring American consternation and British glee, showed that the capture of Ticonderoga was not to help the invaders in the least. On the contrary, it straightway became a burden, for it detained an eighth part of Burgoyne’s force in garrison at a time when he could ill spare it.

Burgoyne’s difficulties beginIndeed, alarming as his swift advance had seemed at first, Burgoyne’s serious difficulties were now just beginning, and the harder he laboured to surmount them the more completely did he work himself into a position from which it was impossible either to advance or to recede. On the 10th of July his whole army had reached Skenesborough (now Whitehall), at the head of Lake Champlain. From this point to Fort Edward, where the American army was encamped, the distance was twenty miles as the crow flies; but Schuyler had been industriously at work with those humble weapons the axe and the crowbar, which in warfare sometimes prove mightier than the sword. The roads, bad enough at their best, were obstructed every few yards by huge trunks of fallen trees, that lay with their boughs interwoven. Wherever the little streams could serve as aids to the march, they were choked up with stumps and stones; wherever they served as obstacles which needed to be crossed, the bridges were broken down. The country was such an intricate labyrinth of creeks and swamps that more than forty bridges had to be rebuilt in the course of the march. Under these circumstances, Burgoyne’s advance must be regarded as a marvel of celerity. He accomplished a mile a day, and reached Fort Edward on the 30th of July.

Schuyler wisely evacuates Fort EdwardIn the mean time Schuyler had crossed the Hudson, and slowly fallen back to Stillwater. For this retrograde movement fresh blame was visited upon him by the general public, which at all times is apt to suppose that a war should mainly consist of bloody battles, and which can seldom be made to understand the strategic value of a retreat. The facts of the case were also misunderstood. Fort Edward was supposed to be an impregnable stronghold, whereas it was really commanded by highlands. The Marquis de Chastellux, who visited it somewhat later, declared that it could be taken at any time by 500 men with four siege-guns. Now for fighting purposes an open field is much better than an untenable fortress. If Schuyler had stayed in Fort Edward, he would probably have been forced to surrender; and his wisdom in retreating is further shown by the fact that every moment of delay counted in his favour. The militia of New York and New England were already beating to arms. Some of those yeomen who were with the army were allowed to go home for the harvest; but the loss was more than made good by the numerous levies which, at Schuyler’s suggestion and by Washington’s orders, were collecting under General Lincoln in Vermont, for the purpose of threatening Burgoyne in the rear.

Enemies gathering in Burgoyne’s rearThe people whose territory was invaded grew daily more troublesome to the enemy. Burgoyne had supposed that it would be necessary only to show himself at the head of an army, when the people would rush by hundreds to offer support or seek protection. He now found that the people withdrew from his line of advance, driving their cattle before them, and seeking shelter, when possible, within the lines of the American army. In his reliance upon the aid of New York loyalists, he was utterly disappointed; very few Tories joined him, and these could offer neither sound advice nor personal influence wherewith to help him. When the yeomanry collected by hundreds, it was only to vex him and retard his progress.

Use of Indian auxiliariesEven had the loyalist feeling on the Vermont frontier of New York been far stronger than it really was, Burgoyne had done much to alienate or stifle it by his ill-advised employment of Indian auxiliaries. For this blunder the responsibility rests mainly with Lord North and Lord George Germain. Burgoyne had little choice in the matter except to carry out his instructions. Being a humane man, and sharing, perhaps, in that view of the “noble savage” which was fashionable in Europe in the eighteenth century, he fancied he could prevail upon his tawny allies to forego their cherished pastime of murdering and scalping. When, at the beginning of the campaign, he was joined by a party of Wyandots and Ottawas, under command of that same redoubtable Charles de Langlade who, twenty-two years before, had achieved the ruin of Braddock, he explained his policy to them in an elaborate speech, full of such sentimental phrases as the Indian mind was supposed to delight in.

Burgoyne’s address to the chiefsThe slaughter of aged men, of women and children and unresisting prisoners, was absolutely prohibited; and “on no account, or pretense, or subtlety, or prevarication,” were scalps to be taken from wounded or dying men. An order more likely to prove efficient was one which provided a reward for every savage who should bring his prisoners to camp in safety. To these injunctions, which must have inspired them with pitying contempt, the chiefs laconically replied that they had “sharpened their hatchets upon their affections,” and were ready to follow their “great white father.”

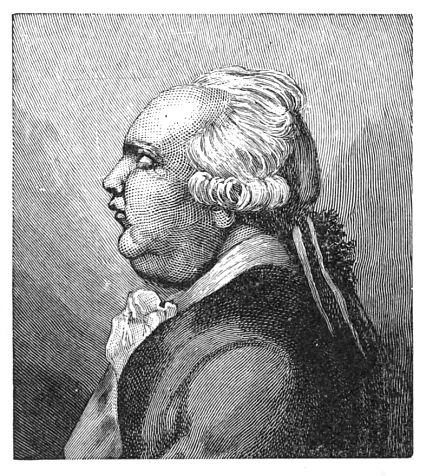

LORD NORTH

It is ridiculed by Burke

The employment of Indian auxiliaries was indignantly denounced by the opposition in Parliament, and when the news of this speech of Burgoyne’s reached England it was angrily ridiculed by Burke, who took a sounder view of the natural instincts of the red man. “Suppose,” said Burke, “that there was a riot on Tower Hill. What would the keeper of his majesty’s lions do? Would he not fling open the dens of the wild beasts, and then address them thus? ‘My gentle lions, my humane bears, my tender-hearted hyenas, go forth! But I exhort you, as you are Christians and members of civilized society, to take care not to hurt any man, woman, or child.’” The House of Commons was convulsed over this grotesque picture; and Lord North, to whom it seemed irresistibly funny to hear an absent man thus denounced for measures which he himself had originated, sat choking with laughter, while tears rolled down his great fat cheeks.

It soon turned out, however, to be no laughing matter. The cruelties inflicted indiscriminately upon patriots and loyalists soon served to madden the yeomanry, and array against the invaders whatever wavering sentiment had hitherto remained in the country.

The story of Jane McCreaOne sad incident in particular has been treasured up in the memory of the people, and celebrated in song and story. Jenny McCrea, the beautiful daughter of a Scotch clergyman of Paulus Hook, was at Fort Edward, visiting her friend Mrs. McNeil, who was a loyalist and a cousin of General Fraser. On the morning of July 27th, a marauding party of Indians burst into the house, and carried away the two ladies. They were soon pursued by some American soldiers, who exchanged a few shots with them. In the confusion which ensued the party was scattered, and Mrs. McNeil was taken alone into the camp of the approaching British army. Next day a savage of gigantic stature, a famous sachem, known as the Wyandot Panther, came into the camp with a scalp which Mrs. McNeil at once recognized as Jenny’s, from the silky black tresses, more than a yard in length. A search was made, and the body of the poor girl was found hard by a spring in the forest, pierced with three bullet wounds. How she came to her cruel death was never known. The Panther plausibly declared that she had been accidentally shot during the scuffle with the soldiers, but his veracity was open to question, and the few facts that were known left ample room for conjecture. The popular imagination soon framed its story with a romantic completeness that thrust aside even these few facts. Miss McCrea was betrothed to David Jones, a loyalist who was serving as lieutenant in Burgoyne’s army. In the legend which immediately sprang up, Mr. Jones was said to have sent a party of Indians, with a letter to his betrothed, entreating her to come to him within the British lines that they might be married. For bringing her to him in safety the Indians were to receive a barrel of rum. When she had entrusted herself to their care, and the party had proceeded as far as the spring, where the savages stopped to drink, a dispute arose as to who was to have the custody of the barrel of rum, and many high words ensued, until one of the party settled the question offhand by slaying the lady with his tomahawk. It would be hard to find a more interesting example of the mushroom-like growth and obstinate vitality of a romantic legend. The story seems to have had nothing in common with the observed facts, except the existence of the two lovers and the Indians and a spring in the forest.[12] Yet it took possession of the popular mind almost immediately after the event, and it has ever since been repeated, with endless variations in detail, by American historians. Mr. Jones himself – who lived, a broken-hearted man, for half a century after the tragedy – was never weary of pointing out its falsehood and absurdity; but all his testimony, together with that of Mrs. McNeil and other witnesses, to the facts that really happened was powerless to shake the hold upon the popular fancy which the legend had instantly gained. Such an instance, occurring in a community of shrewd and well-educated people, affords a suggestive commentary upon the origin and growth of popular tales in earlier and more ignorant ages.

THE ALLIES – PAR NOBILE FRATRUM[13]

The Indians desert Burgoyne

But in whatever way poor Jenny may have come to her death, there can be no doubt as to the mischief which it swiftly wrought for the invading army. In the first place, it led to the desertion of all the Indian allies. Burgoyne was a man of quick and tender sympathy, and the fate of this sweet young lady shocked him as it shocked the American people. He would have had the Panther promptly hanged, but that his guilt was not clearly proved, and many of the officers argued that the execution of a famous and popular sachem would enrage all the other Indians, and might endanger the lives of many of the soldiers. The Panther’s life was accordingly spared, but Burgoyne made it a rule that henceforth no party of Indians should be allowed to go marauding save under the lead of some British officer, who might watch and restrain them. When this rule was put in force, the tawny savages grunted and growled for two or three days, and then, with hoarse yells and hoots, all the five hundred broke loose from the camp, and scampered off to the Adirondack wilderness. From a military point of view, the loss was small, save in so far as it deprived the army of valuable scouts and guides. But the thirst for vengeance which was aroused among the yeomanry of northern New York, of Vermont, and of western Massachusetts, was a much more serious matter. The lamentable story was told at every village fireside, and no detail of pathos or of horror was forgotten. The name of Jenny McCrea became a watchword, and a fortnight had not passed before General Lincoln had gathered on the British flank an army of stout and resolute farmers, inflamed with such wrath as had not filled their bosoms since the day when all New England had rushed to besiege the enemy in Boston.