полная версия

полная версияThe American Revolution

Such a force of untrained yeomanry is of little use in prolonged warfare, but on important occasions it is sometimes capable of dealing heavy blows. We have seen what it could do on the memorable day of Lexington. It was now about to strike, at a critical moment, with still more deadly effect. Burgoyne’s advance, laborious as it had been for the last three weeks, was now stopped for want of horses to drag the cannon and carry the provision bags; and the army, moreover, was already suffering from hunger. The little village of Bennington, at the foot of the Green Mountains, had been selected by the New England militia as a centre of supplies. Many hundred horses had been collected there, with ample stores of food and ammunition. To capture this village would give Burgoyne the warlike material he wanted, while at the same time it would paralyze the movements of Lincoln, and perhaps dispel the ominous cloud that was gathering over the rear of the British army. Accordingly, on the 13th of August, a strong detachment of 500 of Riedesel’s men, with 100 newly arrived Indians and a couple of cannon, was sent out to seize the stores at Bennington. Lieutenant-Colonel Baum commanded the expedition, and he was accompanied by Major Skene, an American loyalist, who assured Burgoyne on his honour that the Green Mountains were swarming with devoted subjects of King George, who would flock by hundreds to his standard as soon as it should be set up among them. That these loyal recruits might be organized as quickly as possible, Burgoyne sent along with the expedition a skeleton regiment of loyalists, all duly officered, into the ranks of which they might be mustered without delay. The loyal recruits, however, turned out to be the phantom of a distempered imagination: not one of them appeared in the flesh. On the contrary, the demeanour of the people was so threatening that Baum became convinced that hard work was before him, and next day he sent back for reinforcements. Lieutenant-Colonel Breymann was accordingly sent to support him, with another body of 500 Germans and two field-pieces.

Stark prepares to receive the GermansMeanwhile Colonel Stark was preparing a warm reception for the invaders. We have already seen John Stark, a gallant veteran of the Seven Years’ War, serving with distinction at Bunker Hill and at Trenton and Princeton. He was considered one of the ablest officers in the army; but he had lately gone home in disgust, for, like Arnold, had been passed over by Congress in the list of promotions. Tired of sulking in his tent, no sooner did this rustic Achilles hear of the invaders’ presence in New England than he forthwith sprang to arms, and in the twinkling of an eye 800 stout yeomen were marching under his orders. He refused to take instructions from any superior officer, but declared that he was acting under the sovereignty of New Hampshire alone, and would proceed upon his own responsibility in defending the common cause. At the same time he sent word to General Lincoln, at Manchester in the Green Mountains, asking him to lend him the services of Colonel Seth Warner, with the gallant regiment which had checked the advance of Fraser at Hubbardton. Lincoln sent the reinforcement without delay, and after marching all night in a drenching rain, the men reached Bennington in the morning, wet to the skin. Telling them to follow him as soon as they should have dried and rested themselves, Stark pushed on with his main body, and found the enemy about six miles distant. On meeting this large force, Baum hastily took up a strong position on some rising ground behind a small stream, everywhere fordable, known as the Walloomsac river. All day long the rain fell in torrents, and while the Germans began to throw up intrenchments, Stark laid his plans for storming their position on the morrow. During the night a company of Berkshire militia arrived, and with them the excellent Mr. Allen, the warlike parson of Pittsfield, who went up to Stark and said, “Colonel, our Berkshire people have been often called out to no purpose, and if you don’t let them fight now they will never turn out again.” “Well,” said Stark, “would you have us turn out now, while it is pitch dark and raining buckets?” “No, not just this minute,” replied the minister. “Then,” said the doughty Stark, “as soon as the Lord shall once more send us sunshine, if I don’t give you fighting enough, I’ll never ask you to come out again!”

Battle of Bennington, Aug. 16, 1777Next morning the sun rose bright and clear, and a steam came up from the sodden fields. It was a true dog-day, sultry and scorching. The forenoon was taken up in preparing the attack, while Baum waited in his strong position. The New Englanders outnumbered the Germans two to one, but they were a militia, unfurnished with bayonets or cannon, while Baum’s soldiers were all regulars, picked from the bravest of the troops which Ferdinand of Brunswick had led to victory at Creveld and Minden. But the worthy German commander, in this strange country, was no match for the astute Yankee on his own ground. Stealthily and leisurely, during the whole forenoon, the New England farmers marched around into Baum’s rear. They did not march in military array, but in little squads, half a dozen at a time, dressed in their rustic blue frocks. There was nothing in their appearance which to a European veteran like Baum could seem at all soldier-like, and he thought that here at last were those blessed Tories, whom he had been taught to look out for, coming to place themselves behind him for protection. Early in the afternoon he was cruelly undeceived. For while 500 of these innocent creatures opened upon him a deadly fire in the rear and on both flanks, Stark, with 500 more, charged across the shallow stream and assailed him in front. The Indians instantly broke and fled screeching to the woods, while yet there was time for escape. The Germans stood their ground, and fought desperately; but thus attacked on all sides at once, they were soon thrown into disorder, and after a two hours’ struggle, in which Baum was mortally wounded, they were all captured. At this moment, as the New England men began to scatter to the plunder of the German camp, the relieving force of Breymann came upon the scene; and the fortunes of the day might have been changed, had not Warner also arrived with his 150 fresh men in excellent order.

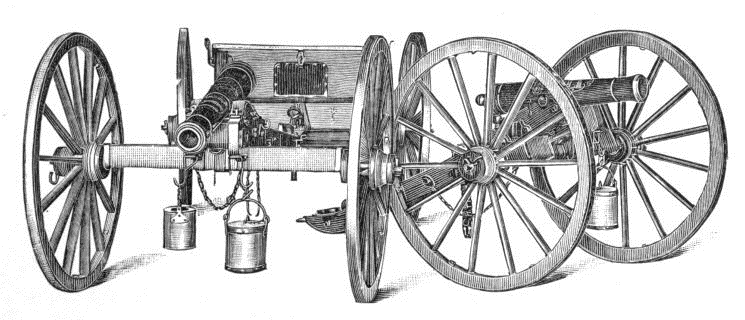

The invading force annihilatedA furious charge was made upon Breymann, who gave way, and retreated slowly from hill to hill, while parties of Americans kept pushing on to his rear to cut him off. By eight in the evening, when it had grown too dark to aim a gun, this second German force was entirely dispersed or captured. Breymann, with a mere corporal’s guard of sixty or seventy men, escaped under cover of darkness, and reached the British camp in safety. Of the whole German force of 1,000 men, 207 had been killed and wounded, and more than 700 had been captured. Among the spoils of victory were 1,000 stand of arms, 1,000 dragoon swords, and four field-pieces. Of the Americans 14 were killed and 42 wounded.

CANNON CAPTURED AT BENNINGTON

Effect of the news; Burgoyne’s enemies multiply

The news of this brilliant victory spread joy and hope throughout the land. Insubordination which had been crowned with such splendid success could not but be overlooked, and the gallant Stark was at once taken back into the army, and made a brigadier-general. Not least among the grounds of exultation was the fact that an army of yeomanry had not merely defeated, but annihilated, an army of the Brunswick regulars, with whose European reputation for bravery and discipline every man in the country was familiar. The bolder spirits began to ask the question why that which had been done to Baum and Breymann might not be done to Burgoyne’s whole army; and in the excitement of this rising hope, reinforcements began to pour in faster and faster, both to Schuyler at Stillwater and to Lincoln at Manchester. On the other hand, Burgoyne at Fort Edward was fast losing heart, as dangers thickened around him. So far from securing his supplies of horses, wagons, and food by this stroke at Bennington, he had simply lost one seventh part of his available army, and he was now clearly in need of reinforcements as well as supplies. But no word had yet come from Sir William Howe, and the news from St. Leger was anything but encouraging. It is now time for us to turn westward and follow the wild fortunes of the second invading column.

COLONEL BARRY ST. LEGER

Advance of St. Leger upon Fort Stanwix

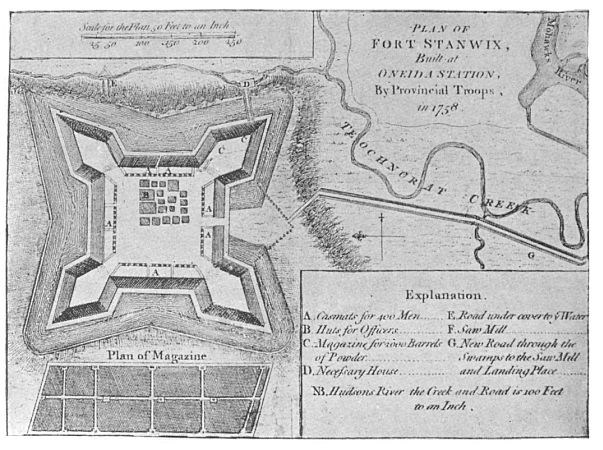

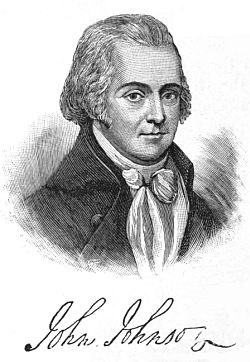

About the middle of July, St. Leger had landed at Oswego, where he was joined by Sir John Johnson with his famous Tory regiment known as the Royal Greens, and Colonel John Butler with his company of Tory rangers. Great efforts had been made by Johnson to secure the aid of the Iroquois tribes, but only with partial success. For once the Long House was fairly divided against itself, and the result of the present campaign did not redound to its future prosperity. The Mohawks, under their great chief Thayendanegea, better known as Joseph Brant, entered heartily into the British cause, and they were followed, though with less alacrity, by the Cayugas and Senecas; but the central tribe, the Onondagas, remained neutral. Under the influence of the missionary, Samuel Kirkland, the Oneidas and Tuscaroras actively aided the Americans, though they did not take the field. After duly arranging his motley force, which amounted to about 1,700 men, St. Leger advanced very cautiously through the woods, and sat down before Fort Stanwix on the 3d of August. This stronghold, which had been built in 1758, on the watershed between the Hudson and Lake Ontario, commanded the main line of traffic between New York and Upper Canada. The place was then on the very outskirts of civilization, and under the powerful influence of Johnson the Tory element was stronger here than in any other part of the state. Even here, however, the strength of the patriot party turned out to be much greater than had been supposed, and at the approach of the enemy the people began to rise in arms. In this part of New York there were many Germans, whose ancestors had come over to America in consequence of the devastation of the Palatinate by Louis XIV.; and among these there was one stout patriot whose name shines conspicuously in the picturesque annals of the Revolution.

Herkimer marches against himGeneral Nicholas Herkimer, commander of the militia of Tryon County, a veteran over sixty years of age, no sooner heard of St. Leger’s approach than he started out to the rescue of Fort Stanwix; and by the 5th of August he had reached Oriskany, about eight miles distant, at the head of 800 men. The garrison of the fort, 600 in number, under Colonel Peter Gansevoort, had already laughed to scorn St. Leger’s summons to surrender, when, on the morning of the 6th, they heard a distant firing to the eastward, which they could not account for. The mystery was explained when three friendly messengers floundered through a dangerous swamp into the fort, and told them of Herkimer’s approach and of his purpose.

Herkimer’s planThe plan was to overwhelm St. Leger by a concerted attack in front and rear. The garrison was to make a furious sortie, while Herkimer, advancing through the forest, was to fall suddenly upon the enemy from behind; and thus it was hoped that his army might be crushed or captured at a single blow. To ensure completeness of coöperation, Colonel Gansevoort was to fire three guns immediately upon receiving the message, and upon hearing this signal Herkimer would begin his march from Oriskany. Gansevoort would then make such demonstrations as to keep the whole attention of the enemy concentrated upon the fort, and thus guard Herkimer against a surprise by the way, until, after the proper interval of time, the garrison should sally forth in full force.

Plan of Fort Stanwix

In this bold scheme everything depended upon absolute coördination in time. Herkimer had dispatched his messengers so early on the evening of the 5th that they ought to have reached the fort by three o’clock the next morning, and at about that time he began listening for the signal-guns. But through some unexplained delay it was nearly eleven in the forenoon when the messengers reached the fort, as just described. Meanwhile, as hour after hour passed by, and no signal-guns were heard by Herkimer’s men, they grew impatient, and insisted upon going ahead, without regard to the preconcerted plan. Much unseemly wrangling ensued, in which Herkimer was called a coward and accused of being a Tory at heart, until, stung by these taunts, the brave old man at length gave way, and at about nine o’clock the forward march was resumed. At this time his tardy messengers still lacked two hours of reaching the fort, but St. Leger’s Indian scouts had already discovered and reported the approach of the American force, and a strong detachment of Johnson’s Greens under Major Watts, together with Brant and his Mohawks, had been sent out to intercept them.

Thayendanegea prepares an ambuscadeAbout two miles west of Oriskany the road was crossed by a deep semicircular ravine, concave toward the east. The bottom of this ravine was a swamp, across which the road was carried by a causeway of logs, and the steep banks on either side were thickly covered with trees and underbrush. The practised eye of Thayendanegea at once perceived the rare advantage of such a position, and an ambuscade was soon prepared with a skill as deadly as that which once had wrecked the proud army of Braddock. But this time it was a meeting of Greek with Greek, and the wiles of the savage chief were foiled by a desperate valour which nothing could overcome. By ten o’clock the main body of Herkimer’s army had descended into the ravine, followed by the wagons, while the rear-guard was still on the rising ground behind.

Battle of Oriskany, Aug. 6, 1777At this moment they were greeted by a murderous volley from either side, while Johnson’s Greens came charging down upon them in front, and the Indians, with frightful yells, swarmed in behind and cut off the rear-guard, which was thus obliged to retreat to save itself. For a moment the main body was thrown into confusion, but it soon rallied and formed itself in a circle, which neither bayonet charges nor musket fire could break or penetrate. The scene which ensued was one of the most infernal that the history of savage warfare has ever witnessed. The dark ravine was filled with a mass of fifteen hundred human beings, screaming and cursing, slipping in the mire, pushing and struggling, seizing each other’s throats, stabbing, shooting, and dashing out brains. Bodies of neighbours were afterwards found lying in the bog, where they had gone down in a death-grapple, their cold hands still grasping the knives plunged in each other’s hearts.

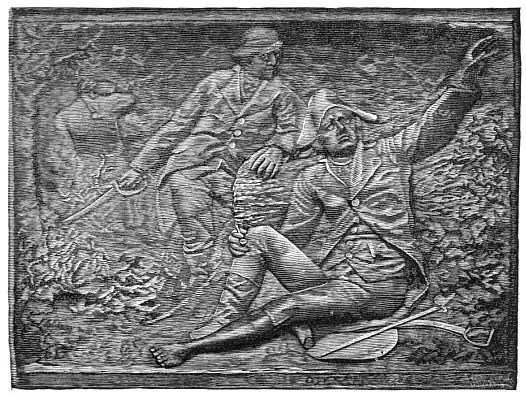

BAS-RELIEF ON THE HERKIMER MONUMENT AT ORISKANY

Early in the fight a musket-ball slew Herkimer’s horse, and shattered his own leg just below the knee; but the old hero, nothing daunted, and bating nothing of his coolness in the midst of the horrid struggle, had the saddle taken from his dead horse and placed at the foot of a great beech-tree where, taking his seat and lighting his pipe, he continued shouting his orders in a stentorian voice and directing the progress of the battle. Nature presently enhanced the lurid horror of the scene. The heat of the August morning had been intolerable, and black thunder-clouds, overhanging the deep ravine at the beginning of the action, had enveloped it in a darkness like that of night. Now the rain came pouring in torrents, while gusts of wind howled through the treetops, and sheets of lightning flashed in quick succession, with a continuous roar of thunder that drowned the noise of the fray.

Retreat of the ToriesThe wet rifles could no longer be fired, but hatchet, knife, and bayonet carried on the work of butchery, until, after more than five hundred men had been killed or wounded, the Indians gave way and fled in all directions, and the Tory soldiers, disconcerted, began to retreat up the western road, while Herkimer’s little army, remaining in possession of the hard-won field, felt itself too weak to pursue them.

At this moment, as the storm cleared away and long rays of sunshine began flickering through the wet leaves, the sound of the three signal-guns came booming through the air, and presently a sharp crackling of musketry was heard from the direction of Fort Stanwix.

Retreat of HerkimerStartled by this ominous sound, the Tories made all possible haste to join their own army, while Herkimer’s men, bearing their wounded on litters of green boughs, returned in sad procession to Oriskany. With their commander helpless and more than one third of their number slain or disabled, they were in no condition to engage in a fresh conflict, and unwillingly confessed that the garrison of Fort Stanwix must be left to do its part of the work alone. Upon the arrival of the messengers, Colonel Gansevoort had at once taken in the whole situation. He understood the mysterious firing in the forest, saw that Herkimer must have been prematurely attacked, and ordered his sortie instantly, to serve as a diversion.

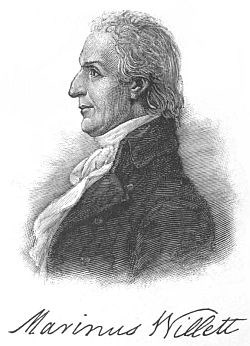

Colonel Willett’s sortieThe sortie was a brilliant success. Sir John Johnson, with his Tories and Indians, was completely routed and driven across the river. Colonel Marinus Willett took possession of his camp, and held it while seven wagons were three times loaded with spoil and sent to be unloaded in the fort. Among all this spoil, together with abundance of food and drink, blankets and clothes, tools and ammunition, the victors captured five British standards, and all Johnson’s papers, maps, and memoranda, containing full instructions for the projected campaign.

First hoisting of the stars and stripesAfter this useful exploit, Colonel Willett returned to the fort and hoisted the captured British standards, while over them he raised an uncouth flag, intended to represent the American stars and stripes, which Congress had adopted in June as the national banner. This rude flag, hastily extemporized out of a white shirt, an old blue jacket, and some strips of red cloth from the petticoat of a soldier’s wife, was the first American flag with stars and stripes that was ever hoisted, and it was first flung to the breeze on the memorable day of Oriskany, August 6, 1777.

JOSEPH BRANT: THAYENDANEGEA

Death of Herkimer

Of all the battles of the Revolution, this was perhaps the most obstinate and murderous. Each side seems to have lost not less than one third of its whole number; and of those lost, nearly all were killed, as it was largely a hand-to-hand struggle, like the battles of ancient times, and no quarter was given on either side. The number of surviving wounded, who were carried back to Oriskany, does not seem to have exceeded forty. Among these was the indomitable Herkimer, whose shattered leg was so unskilfully treated that he died a few days later, sitting in bed propped by pillows, calmly smoking his Dutch pipe and reading his Bible at the thirty-eighth Psalm.

For some little time no one could tell exactly how the results of this fierce and disorderly day were to be regarded. Both sides claimed a victory, and St. Leger vainly tried to scare the garrison by the story that their comrades had been destroyed in the forest. But in its effects upon the campaign, Oriskany was for the Americans a success, though an incomplete one. St. Leger was not crushed, but he was badly crippled. The sacking of Johnson’s camp injured his prestige in the neighbourhood, and the Indian allies, who had lost more than a hundred of their best warriors on that fatal morning, grew daily more sullen and refractory, until their strange behaviour came to be a fresh source of anxiety to the British commander. While he was pushing on the siege as well as he could, a force of 1,200 troops, under Arnold, was marching up the Mohawk valley to complete his discomfiture.

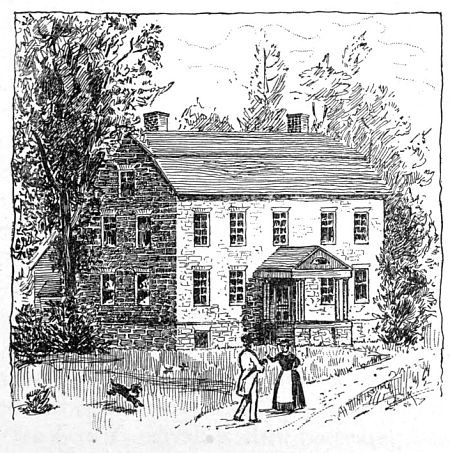

HERKIMER’S HOUSE AT LITTLE FALLS

Arnold arrives at Schuyler’s camp

As soon as he had heard the news of the fall of Ticonderoga, Washington had dispatched Arnold to render such assistance as he could to the northern army, and Arnold had accordingly arrived at Schuyler’s headquarters about three weeks ago. Before leaving Philadelphia, he had appealed to Congress to restore him to his former rank relatively to the five junior officers who had been promoted over him, and he had just learned that Congress had refused the request. At this moment, Colonel Willett and another officer, after a perilous journey through the wilderness, arrived at Schuyler’s headquarters, and bringing the news of Oriskany, begged that a force might be sent to raise the siege of Fort Stanwix. Schuyler understood the importance of rescuing the stronghold and its brave garrison, and called a council of war; but he was bitterly opposed by his officers, one of whom presently said to another, in an audible whisper, “He only wants to weaken the army!” At this vile insinuation, the indignant general set his teeth so hard as to bite through the stem of the pipe he was smoking, which fell on the floor and was smashed. “Enough!” he cried. “I assume the whole responsibility. Where is the brigadier who will go?”

and volunteers to relieve Fort StanwixThe brigadiers all sat in sullen silence; but Arnold, who had been brooding over his private grievances, suddenly jumped up. “Here!” said he. “Washington sent me here to make myself useful: I will go.” The commander gratefully seized him by the hand, and the drum beat for volunteers. Arnold’s unpopularity in New England was mainly with the politicians. It did not extend to the common soldiers, who admired his impulsive bravery and had unbounded faith in his resources as a leader.

Accordingly, 1,200 Massachusetts men were easily enlisted in the course of the next forenoon, and the expedition started up the Mohawk valley. Arnold pushed on with characteristic energy, but the natural difficulties of the road were such that after a week of hard work he had only reached the German Flats, where he was still more than twenty miles from Fort Stanwix. Believing that no time should be lost, and that everything should be done to encourage the garrison and dishearten the enemy, he had recourse to a stratagem, which succeeded beyond his utmost anticipation. A party of Tory spies had just been arrested in the neighbourhood, and among them was a certain Yan Yost Cuyler, a queer, half-witted fellow, not devoid of cunning, whom the Indians regarded with that mysterious awe with which fools and lunatics are wont to inspire them, as creatures possessed with a devil. Yan Yost was summarily condemned to death, and his brother and gypsy-like mother, in wild alarm, hastened to the camp, to plead for his life. Arnold for a while was inexorable, but presently offered to pardon the culprit on condition that he should go and spread a panic in the camp of St. Leger.

Yan Yost CuylerYan Yost joyfully consented, and started off forthwith, while his brother was detained as a hostage, to be hanged in case of his failure. To make the matter still surer, some friendly Oneidas were sent along to keep an eye upon him and act in concert with him. Next day, St. Leger’s scouts, as they stole through the forest, began to hear rumours that Burgoyne had been totally defeated, and that a great American army was coming up the valley of the Mohawk. They carried back these rumours to the camp, and toward evening, while officers and soldiers were standing about in anxious consultation, Yan Yost came running in, with a dozen bullet-holes in his coat and terror in his face, and said that he had barely escaped with his life from the resistless American host which was close at hand. As many knew him for a Tory, his tale found ready belief, and when interrogated as to the numbers of the advancing host he gave a warning frown, and pointed significantly to the countless leaves that fluttered on the branches overhead. Nothing more was needed to complete the panic.