Полная версия

Too Big to Walk

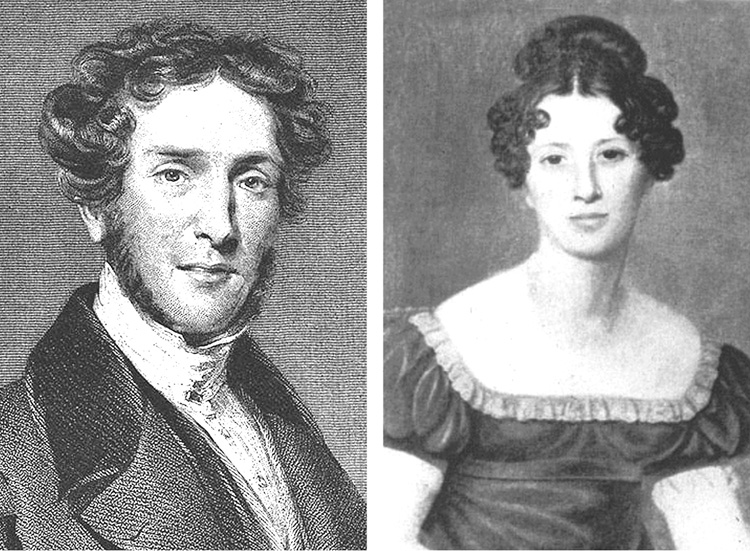

The year 1816 was a crucial watershed for Mantell. He married Mary Ann Woodhouse, a talented young artist, and took on a new post as surgeon at the Royal Artillery Hospital in nearby Ringmer, Sussex. He also published his first scholarly work that year, a book on the minerals in the area around Lewes. Next, he published a magazine article on the rocky strata of southeast Sussex. By this time he was starting to become prominent among the fossil hunters. When Colonel Thomas James Birch decided to auction his entire fossil collection for the benefit of Mary Anning, it was to Mantell that he wrote in March 1820, saying: ‘The sale is for the benefit of the poor woman and her son and daughter at Lyme, who have in truth found almost all the fine things which have been submitted to scientific investigation. I may never again possess what I am about to part with, yet in doing it I shall have the satisfaction of knowing that the money will be well applied.’

It was also in 1820 that Mantell heard of a new source of fossilized bones – the quarries in Tilgate Forest near Crawley, Surrey, some 10 miles (16 km) to the north of Cuckfield, from where most of his specimens had come. He travelled by one-horse chaise and stayed at the Talbot inn, which stands to this day, and from there he rode over to the quarries. Pieces of rock had been set out by the quarrymen for him to peruse and perhaps purchase, and he took a selection to study. We remember the men in palæontology much better than the womenfolk, but – just as Mary Anning regularly provided new and exciting specimens for them to study – Mantell later wrote that he owed his greatest leap forward to his wife, when she stumbled across a find that would finally launch the science that we now know as palæontology.

A devotee of Smith’s geological revelations was Gideon Mantell, an obstetrician and a brilliant amateur fossil hunter, who in 1822 first named a fossil dinosaur – Iguanodon. The fossils were originally thought to be those of a rhinoceros. In 1816 Mary Woodhouse married Gideon Mantell and became his co-worker. She was an accomplished artist and prepared many illustrations for publication. It has been said that Mary was the first to discover iguanodon teeth.

It was the summer of 1822, and Mary Ann was travelling with her husband en route to one of his patients at home. By the side of the road, she noticed a chunky fossil on a pile of discarded rubble and showed it to her husband. It was a huge tooth. This was the crucial discovery, and Gideon launched a full-scale investigation of the Tilgate Forest quarries, looking for more. Mantell did not record until 1827 that he had first been presented with that huge tooth by his wife, but – although they could not know this at the time – this was the tooth of an Iguanodon, a dinosaur that we now know measured 43 feet (13 metres) long and weighed some 4 tons. Other specimens were excavated by a quarryman, Mr. Isaac Leney from Cuckfield, and a selection of fossils was soon amassed. Clearly, they could only have come from a huge animal, and Mantell became increasingly excited.40

By the end of 1822 Gideon Mantell had at least half a dozen of these specimens, so he travelled to Paris the following year and showed them to Cuvier, who formally identified the specimens that the Mantells had collected as ‘the teeth of a gigantic crocodile, the teeth of a rhinoceros [and] bones of an herbivorous animal’ – in reality, the ‘crocodile’ was Megalosaurus and the ‘herbivorous animal’ would eventually prove to be Iguanodon. Mary Anning had recently found a virtually complete Plesiosaurus skeleton, and this was put on display along with the ‘Megalosaurus or great Fossil Lizard of Stonesfield’ that Buckland had brought along, and which Parkinson had included in his book. It had been excavated at Stonesfield. Cuvier was less dismissive of this fossil, describing it as ‘a monitor [lizard] forty feet long and the size of an elephant.’

Gideon and Mary Ann Mantell worked together on their major volume on the fossils of the South Downs, and it was published at about the same date as Parkinson’s book. It was an important book and it launched a more systematic study of fossils. The Mantells’ new book received a royal endorsement from King George IV at Carlton House Palace: ‘His Majesty is pleased to command that his Name should be placed at the head of the Subscription List for four copies.’41

Most of the fine lithographs that Mary Ann meticulously prepared were of shellfish, though towards the end of the plates there were tantalizing glimpses of the scales of the skin of fossil fish, and also a reptilian jawbone, complete with teeth.

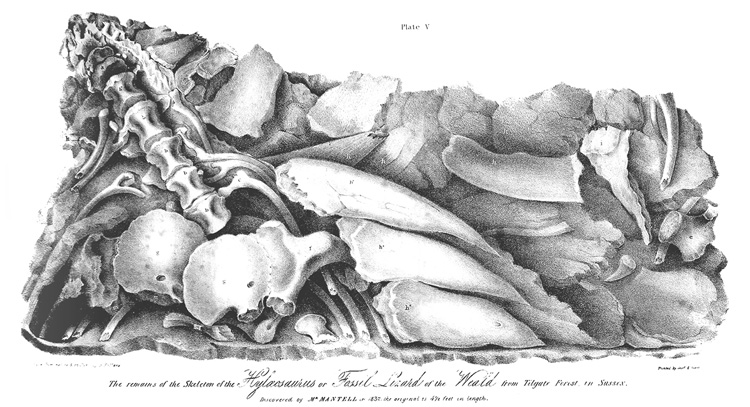

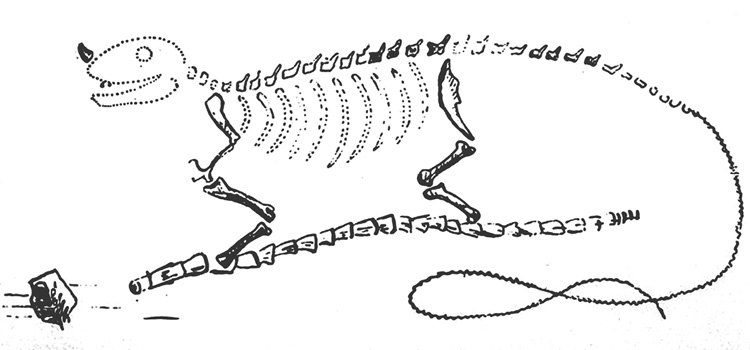

The first engraving of the Hylæosaurus fossil that the Mantells unearthed in the Tilgate Forest quarry in 1832 was redrawn & lithographed by F. Pollard for The Geology of the South East of England, which was published in London a year later.

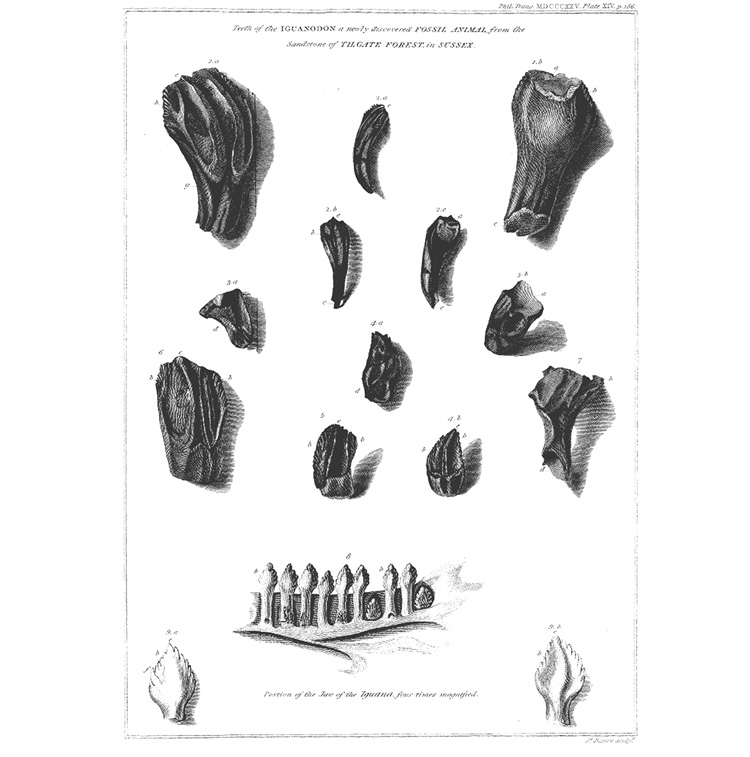

It was the large fossilized teeth that Mary Ann and Mr. Leney had collected that continued to fascinate Gideon Mantell. He compared these teeth with those of an iguana in the collection of the Hunterian Society and became increasingly convinced that his fossils were from a gigantic version of a monitor lizard. He consulted others on his findings, and in 1824 Cuvier wrote again to concede that: ‘I believe they belong to the order of reptiles.’ Mantell was thrilled by this confirmation from such a well-accepted authority, and thought that he might name the creature Iguanosaurus. A colleague, William Daniel Conybeare, by this time dean of Llandaff in Wales and an active amateur collector, suggested that the name be modified. ‘The name you propose,’ he wrote, ‘Iguano Saurus, will hardly do because it is equally applicable to the modern iguana … Iguanodon (having the teeth of an iguana) would be better.’ Mantell agreed, and presented a paper to the Royal Society on February 10, 1825, entitled ‘Notice on the Iguanodon, a newly discovered fossil reptile, from the sandstone of the Tilgate Forest in Sussex.’ His Iguanodon was officially acknowledged as a gigantic prehistoric reptile, and he had drawn a sketch showing the bones they had retrieved superimposed on how he envisaged the rest of the creature. He was impressed by a pointed spike that had been unearthed, and had wrongly assumed that it belonged on the snout (like the horn on a rhinoceros). He drew attention to the creature’s huge hindlegs, which he compared with those of an elephant, and concluded that their bulk was necessary to fit it for a life on land, writing that ‘the legs must have sustained the weight of the body in a manner more nearly resembling those in the pachydermal Mammalia.’

Gideon Mantell illustrated his 1825 paper for the Royal Society with this plate showing the Tilgate Forest iguanadon teeth in comparison with the jaw of an existing iguana. The genus of his fossil has since been reclassified as Therosaurus.

On October 26, 1825, Mantell sent a package of his specimens to Professor Adam Sedgwick at Cambridge University, including ‘casts of the best teeth of the Iguanodon in my collection’ – the originals he kept for himself. Mantell was writing up his notes for a new book on the geology of Sussex and this was to be a landmark publication. Mantell usually referred to it by part of its subtitle: ‘the fossils of the Tilgate Forest’. The specimens were illustrated by his wife Mary Ann in exquisite detail, and have a photographic clarity. For the first time Mantell described the fossil reptiles in detail – the contents page listed them: Crocodiles, Megalosaurus, Iguanodon, Plesiosaurus … these giants of prehistory were now becoming familiar to the academic world. Dinosaurs had at last arrived on the scientific scene.42

The book proved to be a landmark, and its level of detail is astonishing. Mantell discusses with precision the strata in which the fossils were found, dissecting each layer meticulously, so that the book stands today as a definitive statement. This is no amateurish essay into the unknown, but a serious scientific study. Yet the workload was almost unendurable: in his dedication of the book to Davies Gilbert, the Member of Parliament for Bodmin in Cornwall, Mantell wrote: ‘You are fully aware of the disadvantages under which I have laboured, and will generously make every allowance for the imperfections of a work, composed amidst engagements of the most harassing nature.’ Yet he pressed on, and in 1832 discovered the third dinosaur to be scientifically described. It was only half the size of the Iguanodon and Megalosaurus, measuring less than 30 feet (9 metres) long. It was found, again, in strata at Tilgate Forest, and Mantell wrote: ‘I venture to suggest the propriety of referring it to a new genus of saurian … and I propose to distinguish it by the name of Hylæosaurus.’ In spite of his continued success, life was not easy; in 1833 Mantell moved to the seaside resort town of Brighton but could not sustain his medical practice, and, when he became impoverished, his home was converted by the town council into a museum.

The following year, Mantell received some dramatic news: Iguanodon fossils had suddenly been found in a quarry near Maidstone, in Kent. He decided to investigate, but by the time he was able to reach the site, the strata had already been blown up with gunpowder (the standard accounts all say that the rocks were ‘dynamited’ but that explosive was not invented for another 30 years). Just one fossil-bearing slab survived the demands of the quarrymen, and the owner demanded £25 (in 2018 about £1,200 or some $1,600) before he would release it. Mantell didn’t have any spare money, but a group of his friends clubbed together to purchase the rock. It was transported to his home, where it took pride of place in his personal museum. With typical British wit, they called it the Mantell-piece. It proved impossible to separate out the individual bones, so Mantell and his wife worked on reconstructing the appearance of the remains from what they could see. The rock, formally named the Maidstone Slab, can be seen to this day hanging lost and lonely in the dinosaur gallery at the Natural History Museum in London. That is not the new dinosaur gallery; if you follow the signs, you will come to a kind of indoor theme park illustrated with inane cartoons and littered with shops selling plastic souvenirs, fridge magnets and children’s clothing. The new dinosaur display in that museum is like a gloomy version of Disney World, and most of the Victorian specimens are hanging on a high wall in a nearby gallery where few people notice them.

Mantell’s reconstructions of the dinosaur are largely based on this specimen, and he construed it as a quadruped with the proportions of a bear. Mantell made a sketch on paper which showed the bones they could recognize, placing the horn on the nose; and this remained the conventional interpretation for a century. Mantell began to give public lectures on his work at his home museum, and they proved so popular that in 1838 they were published in a single book devoted to the wonders of geology.43

Mantell so liked showing visitors around the collections that he frequently overlooked charging the standard entrance fee, and the museum soon became insolvent. By now he was becoming desperate, so he offered to sell his entire collection to the British Museum for £5,000 and readily accepted their counter-offer of £4,000 (worth some 50 times as much today: about £200,000 or $250,000). Mantell, who had become the founding father of dinosaurs after his wife’s prescient discovery of that first Iguanodon tooth, cut back on his fossil lectures and moved to Clapham Common in London to concentrate on practising as a physician. In 1839 Mary Ann left Gideon and emigrated to New Zealand, later sending him some new fossil discoveries, while their daughter Hannah died in 1840. The next year saw a dreadful accident: Mantell was caught in the reins of his horse-drawn carriage and severely damaged his back. From that day onwards his spine was painful and problematic. He moved to Pimlico in 1844 and, confined largely to his home, he continued to write books and papers on his discoveries, deadening the constant pain with laudanum, the solution of opium also taken by Mary Anning.

A horn had been found by Mary Mantell among the fossilized iguanodon remains, and when her husband sketched how the animal might have appeared in life, he placed it on the snout. Copies of this incorrect view still appeared 138 years later.

Mantell was the world’s first authority on dinosaurs; four of the five dinosaurs then known had been discovered by him and his wife. Although his life had been enriched with so many discoveries, after his wife left him and he suffered his fall, the pain became increasingly severe. Eventually, on November 10, 1852, Mantell over-dosed on the laudanum, and he died that same afternoon. He was 62. Opinions are divided as to whether it was an accidental overdose or suicide. At autopsy, it was discovered that his vertebral column had curved, a condition now known as scoliosis.44 After the post-mortem dissection, a section of his spine was removed and preserved for study, and it remained in the pathology museum collection of the Royal College of Surgeons of England until 1969 when it was unceremoniously thrown away, due to a lack of storage space. In 2000, to commemorate Mantell’s discovery, a monument was unveiled at Whiteman’s Green, Cuckfield, where Mary Ann had found that first tooth. Maidstone, where the celebrated ‘Mantell-piece’ slab had been retrieved, adopted the iguanodon on its coat of arms. On the town’s crest, a lion supports a shield on the right, with an iguanodon on the left. The official designation is written in the ancient blend of Norman French and English beloved of heraldry specialists:

Arms: Or a Fesse wavy Azure between three Torteaux on a Chief Gules a Lion passant guardant Or.

Crest: Issuant from a Mural Crown Or a Horse’s Head Argent gorged with a Chaplet of Hops fructed proper, Mantled Azure doubled Or.

Supporters: On the dexter side an Iguanodon proper collared Gules and on the sinister side a Lion Or collared Gules.

Motto: AGRICULTURE AND COMMERCE.

In the Maidstone Museum, there is a stained-glass window with the iguanodon on display. Neither the published version of the iguanodon, nor the one in that window, has that horn on the snout.

Maidstone, close to where the Mantells made their discoveries, was granted a coat of arms in 1619. In 1949 the two supporters either side were added, a collared lion (on the right) and an Iguanodon. This version shows the correct snout.

By this time, new fossil dinosaurs were being discovered in France. Remains of a large creature were described in 1838 by a French palæontologist, Jacques Amand Eudes-Deslongchamps, who lived in Normandy. He didn’t have much to go on; bones from the abdomen, a front- and hind-limb, the tail, and three types of ribs. He decided to name it Poekilopleuron from the Greek ποίκιλος (poikilos, varied) and πλευρών (pleuron, rib), and the bones were donated to the Museum of the Faculty of Science at Caen. During World War II an Allied bombing raid demolished the department and all the fossils were destroyed. However, plaster casts had been made, so copies survived in the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris and the Peabody Museum at Yale. This dinosaur was about 23 feet (7 metres) long and weighed about 5 tons. It would have lived 167 million years ago and was similar to Megalosaurus.

Although people are taught that the science of dinosaurs began with Richard Owen, the eminent anatomist, he did not begin his serious research until the 1840s and we have seen how far the study of dinosaurs had already advanced. Owen was certainly brilliant, and he was also a tireless investigator. In his early days he had only a few fragmented fossils available for study, yet from this he was able to deduce something of the appearance of an entire dinosaur, and even gain some insights into dinosaur physiology; yet he was also dishonest, vain, vindictive and quarrelsome. Owen frequently claimed the discoveries of others as his own, and was self-righteous in the extreme. He argued repeatedly with Charles Darwin, and refused to accept the theory of evolution. Owen enrolled at the University of Edinburgh Medical School in 1824 aged 20, but – like Darwin, who enrolled at the same school the following year – he was dissatisfied with the quality of instruction and decided instead to study under John Barclay, a convinced anti-materialist. The great debate of the time was the duality of body and soul, and Barclay firmly insisted that life was founded upon a Vital Principle while the individual identity rested in the Soul. Although science was increasingly seen as offering an explanation for living organisms, Barclay adhered rigidly to his non-material views. Neither Darwin nor Owen graduated in Edinburgh, Owen eventually being apprenticed to John Abernathy in London. A philosopher and surgeon, Abernathy was president of the Royal College of Surgeons, and he was instrumental in obtaining membership of the College for Owen in 1826. Charles Darwin, meanwhile, went on his extended holiday as the travelling companion to the captain of HMS Beagle.

Owen’s first professional task was to assist William Clift, conservator of the Royal College of Surgeons, in cataloguing the collection of 13,000 human and zoological specimens that had been amassed by the eminent surgeon John Hunter. A previous custodian of the papers had been Sir Everard Home, that unscrupulous surgeon who had published many of Hunter’s discoveries as his own, and who set fire to the entire archive when an investigation into his conduct loomed near. It fell to Owen to identify what remained in order to rebuild the list. By 1830 he had sorted the documents and identified every anatomical specimen, and was about to publish the full catalogue of the Hunterian Collection. By that time he was accepted as the main authority on Hunter’s voluminous work. In July 1835 he married Clift’s daughter, Caroline Amelia, and they had one son, William. In 1837 Owen was charged with delivering the first series of Hunterian Public Lectures, and his reputation grew to such an extent that he was appointed to teach natural history to the children of Queen Victoria; but his professional attitude remained obdurate, demanding and unpleasant. Charles Darwin (who attended many of Owen’s lectures) wrote later that Owen became his enemy after the Origin of Species was published ‘not owing to any quarrel between us, but as far as I could judge out of jealousy at its success.’

Fossil dinosaurs were also being discovered elsewhere in England. In the late summer of 1834, the curator of the Bristol Institution, Samuel Stutchbury, accompanied his surgeon friend Henry Riley on an expedition to Clifton. Riley had been intrigued by the news of the newly discovered ‘saurian’ fossils and took his friend to prospect in the quarry of Durdham Down, on the outskirts of Bristol. There were repeated reports of strange bones being discovered by quarrymen. It seemed that these bones might also be from gigantic prehistoric reptiles, and a short report was published in the U.S. in 1835.45

Theirs proved to be a small dinosaur, measuring some 6 feet 6 inches (2 metres) in length and weighing no more than 55 pounds (25 kg). The men were a diligent pair of investigators and they made a significant observation: in lizards, the roots of the teeth merge with the jawbone, but they noted that their dinosaur was different. It possessed tooth sockets, much like those of mammals. In their formal paper the following year they gave their discovery its name: Thecodontosaurus, derived from the Greek θήκή (thēkē, socket) and οδους (odous, tooth) – so here was yet another new dinosaur for scientists to study.46

Their searches also turned up teeth of phytosaurian dinosaurs that they named Paleosaurus cylindrodon and P. platyodon. Although they didn’t know it, that generic name had already been thought up by Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, so the proposed name was soon abandoned. As Thecodontosaurus this became the fifth dinosaur to be academically named, following Megalosaurus, Iguanodon, Streptospondylus and Hylæosaurus. The fossil was later provided with an appropriate species name, T. antiquus.

Palæontology has long attracted peculiar people, and few were more eccentric than a collector named Thomas Hawkins. Although we imagine the early palæontologists trudging across barren rocks and scrambling into quarries, many of them, as we have seen, adopted a more leisurely approach – they simply purchased specimens dug up by quarrymen, or bought them from specialist dealers like Mary Anning. The young Hawkins was loquacious, brash and bullying, difficult to get on with and given to outbursts of pugnacious prose. He was the son of a wealthy farmer who, rather than encouraging his wayward son to work with him on the family farm in Somerset, gave him a generous allowance to stay away. As a result, the young Hawkins was able to indulge his new passion for fossil collecting and proudly boasted that, by the age of 20 (in 1830), he already had a large and varied collection. He used to wander round the quarries near Walton and Street in Somerset, watching out for discoveries the quarrymen were making. On several occasions, he saw a priceless fossil in a slab of rock that a worker was about to break up and he promptly stepped in with an offer of largesse that could not be refused. He soon gained a reputation for being someone who would pay good money for these fossils whenever they came to light, and so his collection grew, while he had no need to soil his hands by digging. Yet he soon encountered a problem faced by every collector: fossil remains were hardly ever complete. Quite often, valuable fragments were lost as stone was chipped away from the specimen. Dinosaur skeletons usually had limbs missing and often there was no skull (as in the case of Anning’s first ichthyosaur, and the Brontosaurus later described by Marsh). Early in his career, Hawkins became adept at cleaning up fossils and replaced any parts that were missing with dyed plaster. Today, it is acceptable to create an entire dinosaur skeleton from just a few fossil fragments, but at that time any restoration was frowned upon. Mantell summed up Hawkins perfectly as ‘a very young man who has more money than wit’.

Hawkins was a proselytizing Christian and firmly believed in Adam and Eve. Yet he also followed the latest trends in scientific discovery, and formed the view that fossils could reveal what the world was like before humans had been created. The early Earth, he thought, was an alien and hostile place, bathed in murky darkness that sunlight could not penetrate, and peopled by strange monstrous beings that were intent on destruction. On one of his casual visits to a quarry, he found that the tail of a huge ichthyosaur had been laid bare by a workman. The men had agreed to dig out the rest in a few days’ time, but Hawkins was insistent that the job should be done at once. It was already dusk – but he made them fetch candles and lamps, and work on through the night. Eventually, the rocky strata bearing the fossil were laid out in pieces on a wagon, ready to be transported to Hawkins’ home on the farm. It took him several weeks to chip away the rock to release the whole animal, but in the end he was confronted by an ichthyosaur measuring some 7 feet (2 metres) from nose to tail. The hunks of rock bearing the skeleton were assembled together in a wooden frame, and the result was an entire animal – or almost entire. Whatever was missing, Hawkins created out of plaster that he carefully stained to match the rest of the rock. This gave a convincing result – at least, it did for anybody who wanted to be impressed by the entire creature. For the palæontologists of the time, it posed problems. If you were not certain whether the fossil was entire, it was impossible to tell the real fossil from the replacement plaster, so describing the skeleton accurately would be scientifically invalid.