Полная версия

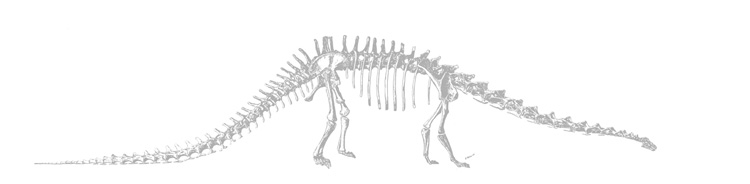

Too Big to Walk

None of this mattered to the irrepressible and domineering Hawkins. Within a few weeks he had himself forgotten which parts of a fossil were original and which he had created from plaster. The creature looked impressive in its apparent completeness, and that was all that mattered to him. His wish was not to pursue scholarship, but to exhibit monsters from a bygone age. If they had pieces missing, he felt it his duty to bring them back to a state of perfection – only then could their prehistoric magnificence be appreciated. His is a very modern attitude. Present-day palæontologists think nothing of recreating vast skeletons of imaginary dinosaurs from plastic, when in reality only a very few bones have been discovered. What was considered unprofessional in Hawkins’ time is carried out on a grander scale today.

In 1833 Hawkins heard that an ichthyosaur skeleton had emerged on low-lying rocks at Lyme Regis. He travelled to the town, and discovered that it could be accessed only at low tide. Hawkins paid a guinea for the finder to grant him the right to own the fossil (£1 1s, now worth about £60 or $80) and told him to assemble a group of workmen, ready to excavate the entire skeleton. He could not resist telling Mary Anning of his find, and she warned him that the rock in which this fossil lay was likely to crumble as it dried. She said it was marl, and she knew that it was rich in iron pyrites (fool’s gold, FeS2). For the next few days no work took place – storms blew in from the west and the beaches were suddenly inaccessible.

By the time the sky had cleared and the winds had dropped, Hawkins was desperate to extract his new fossil from the beach. At low tide the men were sent to work, and they managed to dig out a large hunk of rock which contained the entire skeleton. It was taken to Hawkins’ home where he set to work with his ‘magic chisel’, and within weeks it was ready for display. Any parts that were missing were created out of the plaster, so the finished result owed as much to Hawkins’ creative impulses as it did to nature. By this time, he was spending the winter months in London, mingling whenever he could with the great palæontologists of the day, and he soon managed to become acquainted with William Buckland. Buckland expressed admiration for Hawkins’ fossil collection. He was particularly impressed by the pristine cleanliness of the specimens Hawkins had prepared and also by their astonishing completeness. Hawkins was delighted, and carefully cultivated the relationship, talking always of the might of the Creator, the power of nature, and the evil intent of these denizens from the unfathomable past. These fossils represented grim brutes, he insisted, lusting for blood. Encouraged by Buckland, Hawkins soon set about writing up his discoveries for publication. Many of them appeared in his first book, which came out in 1834.47

The text was filled with imprecations about the majesty of the creation, and the evil of the monsters that mankind had overcome. He solicited Buckland’s support for a proposal to sell his fossil collection to the British Museum for £4,000 (now about £200,000 or $240,000). The management would have none of it, and asked for external opinions as to the real value. Buckland was recommended as a referee by Hawkins, and Mantell was also asked to provide a valuation. Buckland totted up the individual specimens, and provisionally said they were worth between £1,000 and £1,500. Eventually, he decided upon £1,250 as the right price. Mantell separately sent in his own valuation; it came to almost exactly the same sum of money. Doubtless the two men had discussed the total between them, for surely this could not have been coincidence. They wrote to Hawkins, who replied in his oleaginous and glowingly complimentary tone, praising both men for their scholarship and wisdom, and proposing that – as a gesture of his own generosity – the price could perhaps be £2,300. Eventually, after further argument, Hawkins reluctantly accepted £1,250.

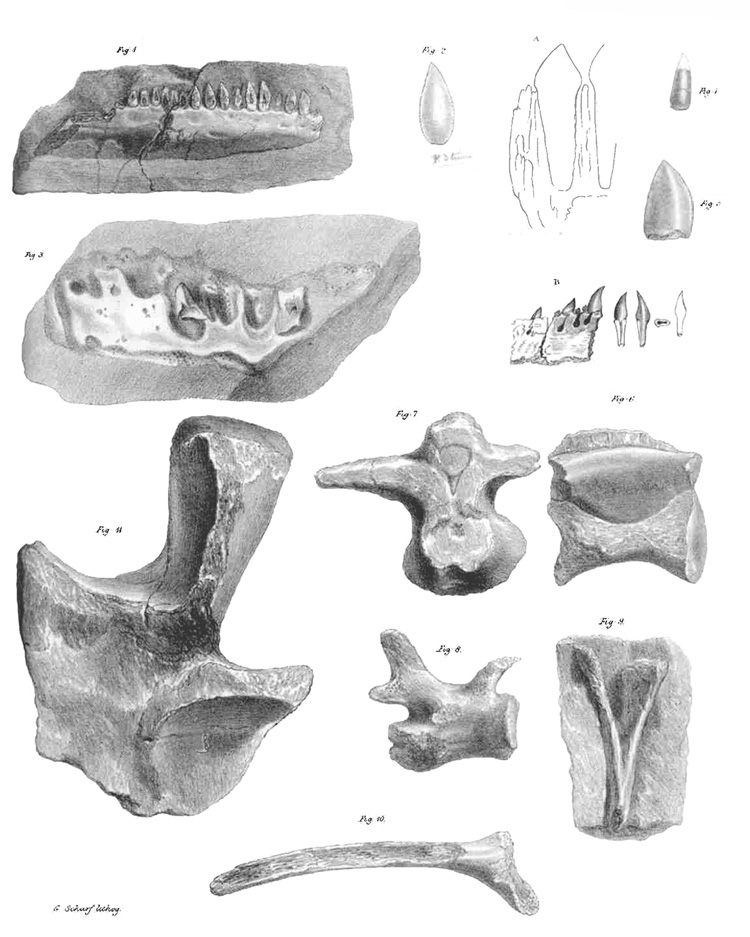

Henry Riley and Samuel Stutchbury found fossils of Thecodontosaurus at Clifton near Bristol in 1834, and their paper illustrated the jaw, teeth, part of the ilium, vertebræ and a rib (bottom). The genus was not recognized as a dinosaur until 1870.

No sooner were the specimens in the museum’s possession in 1835 than the Keeper of Natural History, Charles König, began to make arrangements for them to go on display. His first choice was a magnificent specimen of an ichthyosaur measuring 25 feet (7.5 metres) long. Everything was immaculate, and the skeleton was perfect in every detail. Naturally, König was concerned; no fossil is ever likely to be entirely complete. Yet nothing seemed to be wrong with the skeleton. Curiously, he looked again at the illustration that Hawkins had printed in his catalogue of the collection – and suddenly he could see something odd. The original lithograph showed that the skeleton had not been complete when Hawkins had first illustrated it. Half the tail was missing, and the right forelimb was shown only as a dotted outline, indicating that it was not present when the fossil had been found. The ‘perfect’ skeleton had been made up with dyed plaster. Hawkins had protested in his negotiations that his perfect specimens were all genuine, and were testimony to his skill as a conservator, but it was suddenly clear how he had been improving on nature. Buckland and Mantell were both informed immediately, since König now felt that the specimens were worth far less than the museum had paid. He wrote to say that the fossils could not be put on display after all, since so much was plaster, and said that he would await further instructions. Buckland, against all expectations, rose to the defence of Hawkins. He insisted that no suggestion had ever been made that the specimens were entirely natural. It was only to be expected, he went on, that repairs here and there were necessary in restoring a skeleton, and there was definitely no hint of ‘fraud or collusion’ on his part.

None of this debacle helped the museum’s reputation, which was already being investigated by an inquiry set up by the House of Commons. When König came before the committee, he was cautious about the whole affair, admitting that the skeletons were less than perfect, and agreeing that the price of £1,250 may have been a little more than the fossil collection was worth. Hawkins railed against König, accusing him of pretending that the specimens were imperfect, when in fact all such specimens had merely been cosmetically improved. Mantell thought that Hawkins had been guilty of double-dealing, but put it down to mental instability. The specimen, along with others from the collection, is in the collections of the Natural History Museum in London, identified as Temnodontosaurus platyodon. You can still see tiny indentations all over the specimen. These are the dents left by the point of König’s knife, as he probed to distinguish between plaster and stone. All the plaster additions were subsequently painted to be subtly different, and this reveals that – in addition to the forelimb and the tail – many of the ribs, the tips of the hindlimbs, and even a vertebra, had all been constructed out of plaster by Hawkins. In truth, the skeleton is partly faked and was worth considerably less than a perfect specimen.

Not only was Hawkins unreliable as a conveyor of fossils, but in his writing he frequently substituted his own invented Latin names for those already granted to the fossils he found. He often complained that neither Latin nor Greek was good enough for naming fossils – the language in which they should be named, he insisted, was Hebrew. On he rambled, and soon published a second book, with yet more of his startling revelations. The book has an extraordinary style and is virtually unreadable. Here, for example, is a passage from Chapter V:

The sublime discloses itself only in the silence of which we speak, when, by the most stupendous Efforts of Intellect, by the revivification of Worlds, by the inhabitation thereof of all the Creatures which the labouring Soul can re-articulate, we stand in a Presence which has not, nor ever shall have, one sympathy with ourselves; those Worlds, those antipodal Populations, that Presence passion less, and silent dead; I say the instruments of a few bones verify a Sublimity before which no man can stand unappalled.

And so it drones on, perhaps the most impenetrable prose in the history of science.48

When Hawkins heard of the findings of the House of Commons Committee and its report on the part-plaster skeletons, he immediately threatened to sue for defamation. He was given to litigation. Thus, when a visitor at a nearby property casually picked some fruit from his strawberry patch, Hawkins was accused of using ‘disproportionate violence’ in protesting. He ended up in a legal dispute, meanwhile declaring himself the Earl of Kent.

Richard Owen was becoming increasingly intrigued by the reports of fossilized giant reptiles, and knew of some bones that had been described by an amateur palæontologist, John Kingdon, in a communication to the Geological Society of June 1825. Most learned opinion at the time was still that these were fossils of familiar creatures – porpoises, perhaps, or possibly extinct crocodiles – but Owen was an experienced anatomist and was certain this was wrong. In 1841 he decided the newly discovered fossils represented reptilian animals and he named the genus Cetiosaurus. He was only half right – although Owen had correctly determined that these were reptiles, he concluded they were swimming creatures, somewhat like plesiosaurs, which is why he coined the name cetiosaur from the Greek κήτειος (kèteios, sea-monster). Owen wanted to learn more, and one day late in 1841 he hastened to 15 Aldersgate Street, near St Paul’s Cathedral, to visit his colleague William Devonshire Saull, a businessman and an avid collector of antiquities. Saull had amassed a collection of 20,000 specimens (most of them antiquities from the Middle East) which he had carefully catalogued and labelled. Many were of geological specimens, and some – the important specimens that Owen wanted to inspect – were fossils. Saull was a long-standing friend of Mantell, and they had often exchanged specimens. Among the many relics Saull showed him, Owen picked up a piece of Iguanodon bone, and turned it over in his hands. He knew of the various other gigantic specimens that collectors had unearthed – Megalosaurus, Mosasaurus, his own Cetiosaurus – and was suddenly inspired. These were not just creatures from the past, reminders of now-extinct worlds populated by animals like those of the present day; Owen became convinced that these all belonged to a single great family of reptiles. He suddenly realized that they were different from all the other reptiles we knew. Whereas present-day lizards have sprawling legs that splay out either side, these giant reptiles had downward-pointing limbs that functioned like columns to support their weight on dry land. He speculated that dinosaurs might have been warm-blooded, and he noted that they had five vertebræ fused to form the pelvic girdle, which he knew was not the case with other reptiles. Later discoveries would show he wasn’t entirely correct (some dinosaurs have different numbers of fused sacral vertebræ), but he was right to recognize these as a new group of huge, extinct monsters. This was a crucial breakthrough, and Owen decided to announce his conclusions at the eleventh annual meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science.

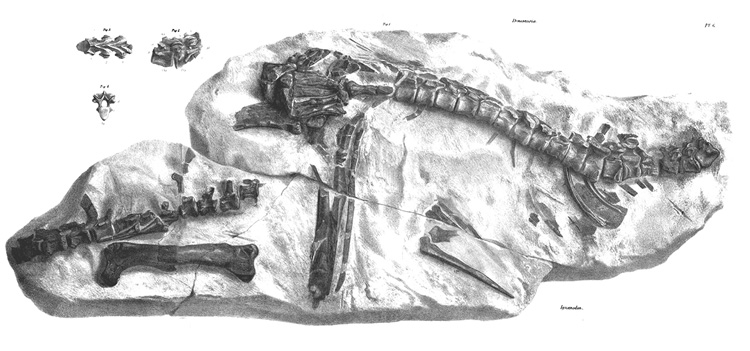

These bones of a young Iguanodon were excavated from Cowleaze Chine on the Isle of Wight and were included by Richard Owen in his monumental work A History of British Fossil Reptiles published by Cassells of London between 1849 and 1884.

The presentation took place on August 2, 1841, on a grey, dank day in London. Owen was a tremendous draw; Cuvier had died in 1832 and Owen had now become Europe’s most renowned zoologist. He had lectured on fossil reptiles before, but this time was different – this was to be his announcement of an entire new class of gigantic reptiles. He began by courteously acknowledging the pioneering discoveries made by William Buckland and Gideon Mantell, both of whom he acknowledged with respect. Then he reviewed what was known about crocodiles, and their similarities to plesiosaurs. And then he moved on to the meat of the argument, and began by describing three genera that he was going to analyze in detail: the herbivorous Iguanodon, the carnivorous Megalosaurus and the armoured Hylæosaurus. These, he said, were different from anything alive. These, he told his audience, formed a distinctly new tribe. Gone was the notion that these were merely long-lost forms of animals that were similar to those still in existence; these were a form of life that nobody had ever seen. His audience was spellbound. So many people had accepted that they were ancient forms of crocodiles, or something similar, but Owen was adamant. Megalosaurus, he explained, was not a gigantic sprawling lizard, but a huge reptile that stood upright on powerful vertical legs. His new image of Iguanodon was of a great monster, standing tall on massive hindlimbs, and towering above the lesser beings that were dotted about its forest landscape. With his majestic prose and his own charismatic powers of oration, Owen had the audience entranced as he radically revised the previous size estimates published by his colleagues. Mantell, he said, had erred in scaling up the size of the limb bones of an iguana to an iguanodon, and reaching an overall length of 75 feet (23 metres). Far better was it to scale up the dimensions of each single vertebra. This posed a problem in knowing how many vertebræ there were in the backbone, for most of the skeletons had a spine that was far from complete. But his calculations worked well: he concluded that an iguanodon would have measured about 28 feet (8.5 metres) from nose to tail, a far more realistic figure that fits well with what we know today. Owen made mistakes of his own in his talk: he described Thecodontosaurus as a lizard, and Cetiosaurus as a crocodile, though we now know that both are sauropod dinosaurs. Sometime after the lecture, he coined a new taxonomic name to define the entire group. He resolved to call them Dinosauria, which he said would distinguish the entire ‘distinct tribe or sub-order of Saurian Reptiles’. The word came from the Greek δεινός (deinos, terrible, awesome) and the familiar σαῦρος (sauros, lizard). It is a curious term, in that dinosaurs are definitely reptiles but are certainly not lizards, nor are they descended from them. This new term Dinosauria first appeared in the Report on British Fossil Reptiles, published the year following Owen’s momentous lecture.49

Throughout his speech, Owen adhered to a strictly creationist view. He was convinced that these creatures had been made by divine providence, and the anatomical peculiarities he observed were, he insisted, the sure sign of intelligent design. He remained obdurate in these opinions, and was strongly opposed to any idea of evolutionary progress. He discussed these matters with Charles Darwin on many occasions, and the two became friends for a while. But when Darwin published his Origin of Species in 1859, Owen was to write a scathing review that he published anonymously. In later years, there was strong animosity between the two. Others had certainly laid the groundwork for this great revelation of the dinosaurs, even though it was Owen who coined the name. To this day, he is heralded as their great discoverer. As the BBC put it, Richard Owen is ‘the man who invented the dinosaur’.

3

The Public Eruption

Many major discoveries were made by forgotten pioneers. So many of the great dinosaurs we know from today’s museums – from Triceratops to Tyrannosaurus – were first unearthed in the U.S., and it is easy to lose sight of what went before. I have explained that dinosaur fossils were known thousands of years before we usually believe they were discovered. Now we can see that there were ideas, images and sculptures of dinosaurs that are far older than the science of palæontology, and it has become clear that curiosity about these massive monsters dates back long before the word ‘dinosaur’ was coined. Indeed, it may have surprised you to see that descriptions and images of fossils were being published in learned books back in the 1600s. Alongside the many men whose names we have encountered stand the women who played a crucial role. Remember that the first person systematically to discover and study prehistoric reptile fossils was a woman, as was the first individual to recognize the significance of a dinosaur tooth, and also the first person to draw perfect studies of fossil dinosaurs for publication. The contributions to mainstream science by women have been widely sidestepped in the past; now would be a good time to reinstate their crucial contributions.

Although the dinosaurs are our theme, palæontologists in England were finding the fossilized remains of other plants and animals and recording them in detail long before dinosaurs were recognized. This research was far more extensive than we usually imagine, and it was captured in a book by John Morris that was published in 1845. Morris was born in 1810 in London and had been privately educated to become a pharmaceutical chemist, yet he became increasingly interested in fossils, and began to publish scientific papers on his discoveries. Morris was a man of prodigious energy and had a remarkable memory, but he disliked speaking in public and was not given easily to writing. His strong point, however, was his fastidious facility for cataloguing. In 1845 he published his greatest work, and one which is a forgotten landmark in palæontology: a comprehensive catalogue of all the British fossils. Morris was subsequently appointed Professor of Geology at University College, London, and was elected president of the Geologists’ Association in London for 1868–1871 and again between 1877 and 1879. His catalogue is rarely mentioned in present-day books, but it is a remarkable document. It extends over 224 pages and lists well over 1,000 different fossil species that had been formally described.1

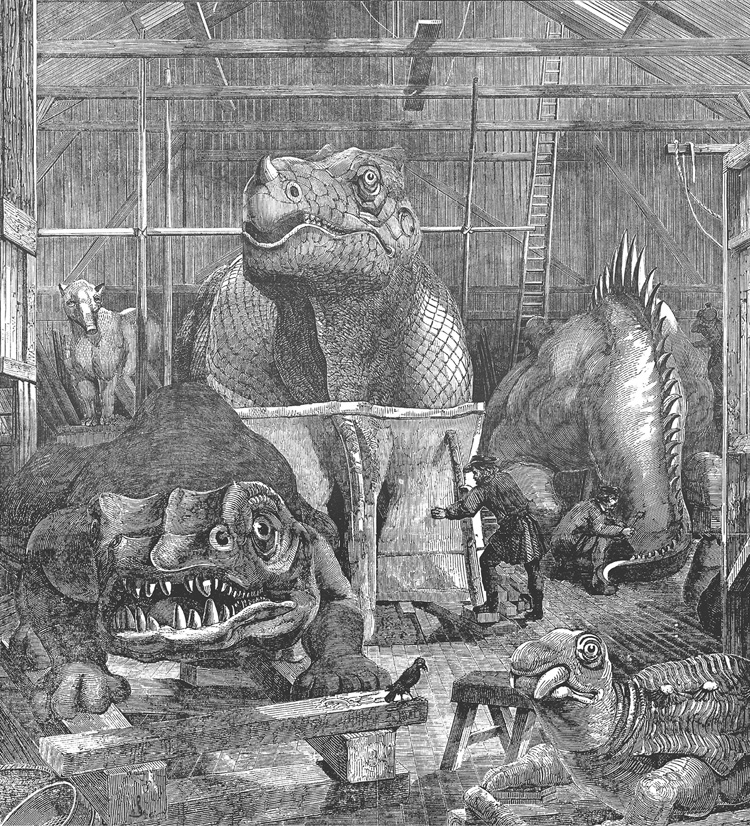

After the Great Exhibition in London of 1851 Sir Richard Owen was asked by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins to advise on the first life-size reconstructions of dinosaurs for the Crystal Palace. The workshop was engraved by Philip Henry Delamotte in 1853.

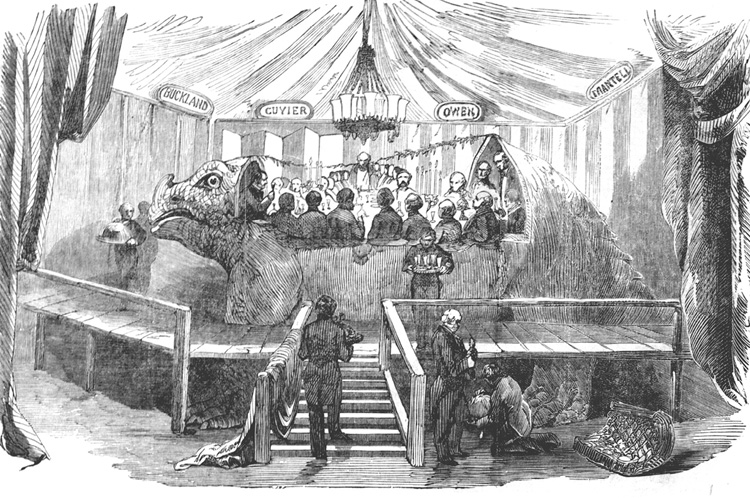

This may well surprise you; it was only three years after Richard Owen published the notion of a dinosaur, yet already there were hundreds of people pursuing palæontology professionally and there were more than 1,000 known species of fossilized life. Already the burgeoning science of palæontology was becoming well established. The public were increasingly interested in the reality of fossils, and the growth of the railway network in Britain meant that visiting the seashore, and collecting specimens as a hobby, was suddenly available to far more people. During the 1830s, steam railways were inaugurated in England, Ireland, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Austria, Australia, Cuba, Canada and the U.S.; and by the end of the 1840s seaside holidays had become popular in England. People combed the beaches for shells and the rocky strata for fossils. Many families acquired their own collections and the lure of fossils steadily increased. There was suddenly the perfect opportunity to publicize the latest research into dinosaurs. The Great Exhibition in London of 1851 had caused an upsurge in popular interest for everything scientific, and Owen was asked by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins to help design the first life-size models of dinosaurs for public display in the grounds of the Crystal Palace. Hawkins had already mentioned the idea to Mantell, but he had turned it down. With Owen as the chief adviser, teams of artisans set to work, creating the first sculptures of dinosaurs that the world had ever seen. On New Year’s Eve 1853, Owen planned a dinner party for 11 prominent academics inside a hollow concrete Iguanodon, even though the model was misconstrued. Mantell had realized in 1849 that an Iguanodon was not the elephantine monster that Owen was constructing, but was more graceful, with slender forelimbs. However, by now it was too late to change the design. A 30-foot (9-metre) representation of the Iguanodon was one of the first of these concrete dinosaurs to be built. To generate publicity, the dinner party had been arranged in the open cast of the partly completed sculpture, with Owen sitting at the head of the table opposite Francis Fuller, the managing director of the Crystal Palace, and with nine more seats squeezed into the space. Once the party was over, the top section was added to the sculpture and the world’s first life-size dinosaur model was complete. It is one of the original sculptures that can be seen to this day at the Crystal Palace Park, in the London borough of Bromley. These dinosaur models are different to our present-day interpretation, though they are vivid examples of how dinosaurs were first interpreted in Victorian England. Apart from true dinosaurs, the 15 sculptures include plesiosaurs and ichthyosaurs, together with a few prehistoric mammals. They survived in a neglected state until 1973, when they were classified as Grade II listed buildings. In 2002 they were meticulously repaired, and were upgraded to Grade I in 2007. Now that they have been properly restored, they should last forever, or at least as long as London.

A unique dinner party took place at 5:00 pm on December 31, 1853, with 11 luminaries seated inside the partly completed Iguanodon. Waterhouse Hawkins sent out the invitations, and Sir Richard Owen was seated at the head of the table.

The quarries of southern England continued to reveal strange new forms of prehistoric life, and often the excavations began with digging into the base of a cliff comprising the desired minerals. One such quarry had been dug out of the cliffs during the 1850s at Black Ven to the east of Lyme Regis. The owner was James Harrison who lived in Charmouth, and who excavated the area for high-quality Charmouth mudstone that dates from the late Sinemurian stage, about 191 million years ago, and was destined for burning into cement. Once in a while, the workmen would retrieve a bone, and these fossils were kept safely as interesting curiosities. Harrison often took them home and displayed them on the mantelpiece or in the hallway for the interest of guests. A surgeon and amateur geologist, Henry Norris, visited Dorset on vacation and became friendly with Harrison. Norris pointed out that these fossils could be important, and even valuable. So, in 1858 the two men sent a parcel containing some broken bones to Owen at the British Museum (Natural History) in London and asked for his opinion. The most conspicuous was a left femur that Owen realized was different from anything previously recorded. He formally described it in 1859, naming the genus Scelidosaurus. Owen’s intention was to name it from the same Greek word from which the word ‘skeleton’ is derived, σκέλος (skelos, hindlimb), because of the strong femur he had examined, but he confused it instead with σκελίς (skelis, rib of beef). He made a mistake: the new dinosaur should have been named Scelodosaurus.