Полная версия

Too Big to Walk

The resonances of these fossils in present-day thinking were alluded to by Reverend Charles Kingsley, when he published a serialized story in MacMillan’s Magazine each month from August 1862 through to March 1863.

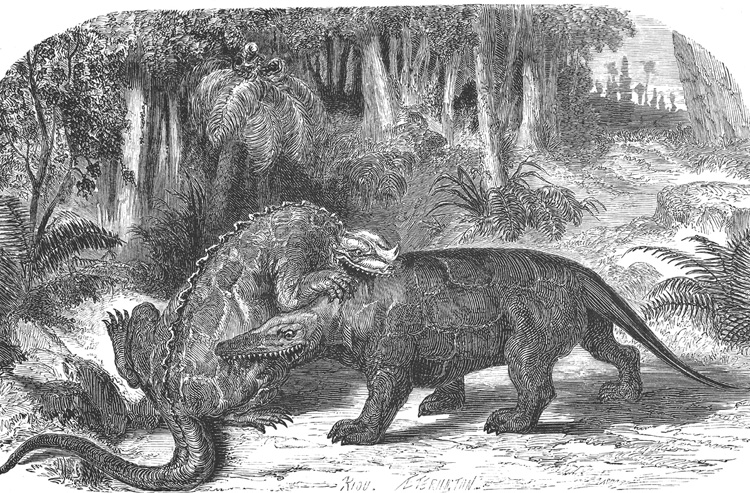

French palæontologist Louis Figuier published his La terre avant le deluge (the world before the flood) in 1863 and it became immensely popular. His illustrator, Edouard Riou, portrayed an Iguanodon and a Megalosaurus fighting with each other.

Did not learned men, too, hold, till within the last twenty-five years, that a flying dragon was an impossible monster? And do we not now know that there are hundreds of them found fossil up and down the world? People call them Pterodactyles: but that is only because they are ashamed to call them flying dragons, after denying so long that flying dragons could exist.

The stories were popular, and were brought together into a single volume in 1863. As a classical moralistic tale for children it has remained in print ever since.33

What was becoming increasingly apparent was the curious consistency in the way rocks had been laid down. This new science began with Friedrich August von Alberti, born in 1795, when he attended a military academy in Stuttgart and took up geology as a hobby. Later he took up employment in the salt production plant at Rottweil, an exquisite medieval town that has still changed little since the 1500s. (This is the place after which Rottweiler dogs are named; they are believed to be the direct descendants of the military breed that Roman soldiers brought during the invasions by the Caesars.) In 1815 Alberti came to recognize the occurrence of three characteristic strata composed of sedimentary deposits. He regularly found three distinct layers: one of red sandstone, capped by chalk, and succeeded by black shales. They occur throughout Germany and were later found to extend across the whole of northwest Europe. In each he found the same characteristic types of fossils and, from the Latin trias (meaning trio), he coined the term Triassic.34 We can now date this geological period as extending from 252.17 to 201.3 million years ago, for this is when the first dinosaurs appeared. The Jurassic period starts where the Triassic leaves off, and that is when dinosaurs first reached their enormous size.

Shortly after Alberti had coined the term Triassic, Jean Baptiste Julien d’Omalius d’Halloy in Belgium recognized the Cretaceous. Born in 1783 in Liège (now in Belgium, but then in the Austrian Netherlands), d’Halloy was sent by his wealthy family to study literature and the classics in Paris. He wanted none of it – geology became his consuming passion. He attended many lectures given by the distinguished naturalists and geologists and he learned everything he could from Georges Cuvier. He loved studying the rocky structure of France, and being of independent means he could travel as widely as he wished. In 1808 he published a learned paper entitled ‘Essai sur la géologie du Nord de la France’ in the Journal des Mines, an extraordinarily wide-ranging subject for someone working independently. It was in this paper that he recognized the distinct nature of coal-bearing strata, which he named Terrain Bituminifère. The name did not gain common currency, but it was the first time that the coal measures were identified as providing a key to an earlier era of the Earth’s history. He also recognized the era of chalk formation and drew sections showing its extent; this he named the Terrain Crétacé, and it was soon recognized in English as the Cretaceous period. He is estimated to have travelled more than 15,000 miles (24,000 km) across France, and he published an immense range of textbooks on geology, all written with clarity and precision, and including some of the first illustrations of the sequence of geological strata.35

Meanwhile, in England, William Coneybeare and William Phillips – both keen amateur geologists – had also concluded that the era of coal-bearing strata must have been confined to one period of time, because of the similar fossil plants that they all contained. Their conclusion substantiated d’Halloy’s designation of his Terrain Bituminifère. This had been an era of gigantic cycads, massive stands of horse-tail Equisetum plants, and huge conifers like today’s monkey-puzzle tree Araucaria. The two English friends realized that this had been an age of swampy forests and – because of the undeniable fact that this was the era that gave us coal – in 1822 they decided to call it the Carboniferous age, from the Latin carbō (coal) and ferō (bearing).36 Today we know this geological period extended from 358.9 to 298.9 million years ago.

Recognizing these great periods – the Jurassic and Triassic, Carboniferous and Cretaceous – had now given palæontologists a greater understanding of the ages through which the Earth had passed. Our present-day countryside reveals the tortured history of churning cliffs and the weathered remains of towering mountains that have resulted from the collisions between continents over millions of years. Now eroded and reduced in stature, the mountain ranges have become rolling hills and the cliffs are cut through like a layered cake so that the æons of prehistory can be seen in strata that stretch back in time. These reveal a timeline of the way that masses of land drifted across the globe, showing us how places like North America and Europe started in the southern Arctic wastes and slowly headed north, where they now extend up towards the northern latitudes of ice and snow. Once, today’s western nations sat at the equator, and the sandy deserts from that time are bequeathed to us as sandstone strata. Later, the land was covered with huge swampy stands of conifers and cycad trees as we drifted past the tropics, and we can see them still in the coal measures. The drifting still goes on. As new rocks are spewed up from a massive split in the Earth’s crust that runs down the middle of the Atlantic, the mid-Atlantic ridge, continental masses on either side are still being forced apart. America and Europe are moving away from each other at the same speed as your nails grow. Clip a couple of millimetres from your toenail and reflect on the fact that the flying distance between New York and London has increased by precisely the same amount.

Some of the rocky strata tell a powerful story of a prehistoric world dominated by massive monsters and strange landscapes. At Kimmeridge Bay in Dorset, for example, you find oil shales from which crude oil seeps just as it does in the world’s greatest petrochemical producing nations. Indeed, there is a nodding donkey oil pump at Kimmeridge, just like those in the American oilfields. Those shale beds formed during the late Jurassic, between 157.3 and 152.1 million years ago, and from them the most beautiful fossils sometimes emerge – bony skeletons of strange swimming plesiosaurs and forbidding dinosaurs. They have been collected as curiosities for centuries. The leading present-day collector is Steve Etches, a plumber who made his living repairing and installing bathroom and kitchen appliances around Kimmeridge. At least, that was in his day job; every moment of his spare time is spent hunting for fossils in the nearby rocky cliffs. He has a keen eye and can spot a fossil when most people see nothing but stone, and his home has been extended to become a private museum. Etches has collected more than 2,000 specimens over the past 35 years. Palæontologists the world over respect his achievements; indeed, in October 2016 the Museum of Jurassic Marine Life was opened a few yards from his home to display the highlights of his collection. It is an exquisite stone building, part of which is the village hall, while the rest is a museum and a laboratory which Etches can enter through a private door and where he can work at will, meeting with the public whenever he wants. This is a unique recognition of his impressive contributions to palæontology, and it was dignified by a formal inauguration ceremony early the next year which my wife and I were privileged to attend.

Steve Etches is the latest in a long line of enthusiasts and, as we have seen, the majority of practitioners of practical palæontology were never formally trained in the discipline. The Dorset shore where Kimmeridge lies has long been known as the ‘Jurassic Coast’ and it extends from Exmouth in East Devon to Studland Bay, near Poole in Dorset, a distance of 100 miles (160 km). It is near the middle of this coast that you will find Lyme Regis, known for its beaches and seaside views, and still a popular venue for fossil collectors. For centuries people have taken home fragments of rock with strange skeletal structures embedded in the surface or marked with the remains of peculiar shells. As interest in studying the natural world began to grow in the nineteenth century, families such as the Annings established businesses collecting fossils they could sell on to enthusiasts. The petrified specimens were originally advertised as thunderbolts or devil’s fingers (belemnites), snake-stones (ammonites) and verteberries (vertebræ). Demand had steadily increased since 1792, as tourism to the south coast of Britain increased when the French revolutionary wars made travel to the continent unsafe. The ancient city of Bath first became a magnet for Georgian tourists, but as visitors were sold the idea of immersion in water rich in minerals, bathing in the sea began to increase in popularity. Bathing machines – little sheds on wheels – sprang up along the coast, from which holidaymakers could demurely emerge and lower themselves into the edge of the ocean. The visitors sought souvenirs, and collecting fossils from the beach became an increasingly popular option, just as enthusiasts had done for centuries.

Among those early collectors was Lieutenant Colonel Thomas James Birch, who used to visit Lyme from his home in Lincolnshire. On a visit in 1820, he became aware that the Annings were in need of money, and he resolved publicly to auction all his fossil collection to help them. Having made no major discoveries for a year, the Annings were at the point of having to sell their furniture to pay the rent. The auction sale at Bullocks auction room in Wareham became a three-day event, with buyers coming from Vienna and Paris, and it raised £400 (over £23,000 or $27,000 today). Mary Anning had become renowned for her expertise and she was mentioned in the media. The Bristol Mirror in 1823 reported:

This persevering female has for years gone daily in search of fossil remains of importance at every tide, for many miles under the hanging cliffs at Lyme, whose fallen masses are her immediate object, as they alone contain these valuable relics of a former world, which must be snatched at the moment of their fall, at the continual risk of being crushed by the half suspended fragments they leave behind, or be left to be destroyed by the returning tide: – to her exertions we owe nearly all the fine specimens of Ichthyosauri of the great collections.

Similarly, the widow of the former Recorder of the City of London, Lady Harriet Silvester, wrote in her diary in 1824:

The extraordinary thing in this young woman is that she has made herself so thoroughly acquainted with the science that the moment she finds any bones she knows to what tribe they belong. She fixes the bones on a frame with cement and then makes drawings and has them engraved. It is certainly a wonderful instance of divine favour – that this poor, ignorant girl should be so blessed, for by reading and application she has arrived to that degree of knowledge as to be in the habit of writing and talking with professors and other clever men on the subject, and they all acknowledge that she understands more of the science than anyone else in this kingdom.

According to an account in The Dragon Seekers, a visiting collector once wrote:

I once gladly availed myself of a geological excursion with Mary Anning and was not a little surprised at her geological tact and acumen. A single glance at the edge of a fossil peeping from the Blue Lias, revealed to her the nature of the fossil and its name and character were instantly announced.37

Mary Anning was a remarkable young woman. It has been claimed that she was the inspiration for the popular tongue-twister: ‘She sells seashells by the seashore’, though Shelley Emmling, who investigated the legend, says this did not appear in print until Terry Sullivan incorporated it into a lyric he published in 1908, so that widely believed origin may be mistaken.38

Mary Anning was not just a fossil collector, or a dealer; she seriously studied what she found and used considerable ingenuity in comparing her fossils with living creatures. She noted that sepia is a brownish ink extracted from present-day cuttlefish, and so – finding fossils of similar animals bearing the traces of fossilized ink-sacs – she made her own ink from the fossils and demonstrated that it could be used in much the same way. When she found fossilized fish, she dissected fresh fish to seek anatomical comparisons. Her diligence and accuracy outshone the work of many professional palæontologists. Among the skeletons that she used to find were the remains of creatures that looked a little like dolphins. These were popularly known as sea dragons or crocodiles. One of her specimens was almost complete and it was inspected by the anatomist and surgeon, Everard Home, an unscrupulous investigator who was responsible for the loss of the Royal Society’s collection of microscopes made by the pioneering microbiologist Antony van Leeuwenhoek. Home also took away the anatomical studies written by John Hunter and began publishing them as his own. Home had worked with Edward Jenner on vaccination, and had bribed the burial party of the Irish giant Charles Byrne, who measured 7 feet 7 in (2.31 metres), having them put rocks into Byrne’s coffin while taking the corpse for Home to study. Even so, Home was cultivating a reputation for being a leading anatomist and he was more than willing to inspect Anning’s latest fossil. Initially, he declared it to be a crocodile; then he changed his mind and decided it was a fish. A year or so later he was saying it was a specimen of a creature that was halfway between fish and crocodiles, and then changed his mind again, deciding it was an amphibian lying between salamanders and lizards. Home was a capricious and devious character, and his personality resonated throughout his work.

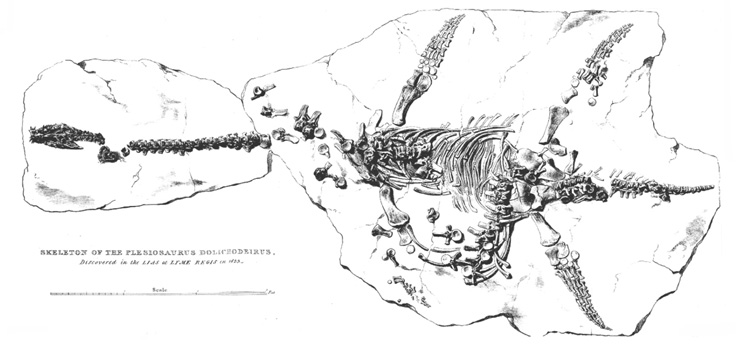

Mary Anning was a student of her subject, and not just a fossil hunter. Many of her finds became popular souvenirs, and this Plesiosaurus skeleton, carefully excavated by Anning in 1823, was prepared as a lithograph by Thomas Webster.

By 1826, six years after the Anning family had been rescued from penury by Birch, Mary had saved just enough money to purchase a shop of her own. The family lived in the rooms above, and they named the premises ‘Anning’s Fossil Depot’. Business was soon flourishing, and the local press reported the opening, mentioning that in the middle of the display was a fine ichthyosaur skeleton. Geologists came to buy specimens from her, including collectors like Gideon Mantell, George William Featherstonhaugh (a curious, ancient English surname simply pronounced ‘fanshaw’) who described her as ‘a very clever funny Creature’, and even royalty: King Frederick Augustus II of Saxony visited her shop to buy a fossil ichthyosaur skeleton. In her later years Anning lost most of her personal money through a bad investment – sources are uncertain how this occurred – and William Buckland approached the British Association for the Advancement of Science and the Government to propose that she was given funds to continue her work. Mary Anning was granted a modest civil list pension by the royal household, in recognition of her contributions to the new science of palæontology. It brought her a trifling sum of just £25 each year, equivalent to £1,200 or some $1,600 in 2018. The Civil List Act 1837 stipulated that these pensions should be granted ‘to such persons only as have just claims on the royal beneficence or who by their personal services to the Crown, or by the performance of duties to the public, or by their useful discoveries in science and attainments in literature and the arts, have merited the gracious consideration of their sovereign and the gratitude of their country.’ Artistic civil list pensioners of the early nineteenth century were granted larger sums; the poets Lord Byron and William Wordsworth each received £300.

By the mid-1840s Mary Anning began to acquire a new reputation – her behaviour was changing, and the local people thought she was becoming an alcoholic. They were wrong: she had developed cancer of the breast. To keep the pain under control she drank increasing amounts of laudanum, a solution of opium, which caused her slurred speech and unsteadiness. When the news of her illness spread, the Geological Society of London launched a fund to help with her expenses, and the new Dorset County Museum appointed her an honorary member. In 1847 Anning died, and members of the Geological Society donated money for a stained-glass window in her memory, which was unveiled in St Michael’s parish church in Lyme Regis in 1850. An inscription nearby says:

This window is sacred to the memory of Mary Anning of this parish, who died 9 March AD 1847 and is erected by the vicar and some members of the Geological Society of London in commemoration of her usefulness in furthering the science of geology, as also of her benevolence of heart and integrity of life.

It was a rare distinction, and so richly deserved. Henry de la Beche, president of the Geological Society of London, delivered a eulogy that was published in the society’s Transactions. No other woman scientist had been similarly commemorated; indeed, the Society did not admit women members until 1904. The president began: ‘I cannot close this notice of our losses by death without adverting to that of one, who though not placed among even the easier classes of society, but one who had to earn her daily bread by her labour, yet contributed by her talents and untiring researches in no small degree to our knowledge of the great Enalio-Saurians, and other forms of organic life entombed in the vicinity of Lyme Regis.’ The eminent Charles Dickens dedicated an article to her in his literary magazine All the Year Round, ending with this tribute: ‘The carpenter’s daughter has won a name for herself, and has deserved to win it.’ More than any other single individual, it was she who launched the study of those curious prehistoric reptiles. Mary Anning was the first full-time professional palæontologist anywhere in the world.

To commemorate Mary Anning’s lifetime of devotion to studying and collecting fossils, in 1850 the Geological Society of London funded this stained-glass window for St. Michael’s Church, Lyme Regis, showing six religious acts of mercy.

Since the start of the nineteenth century, natural philosophy had become a common currency for the public. Amateur investigators were everywhere, and collecting curiosities was the perfect pastime for those with social aspirations. The enlightenment had percolated through society, and a new sense of rational thought was replacing traditional superstition. Yet in modern terms, scientific understanding was limited. The term ‘scientist’ did not exist; that term was not coined until 1834 when William Whewell, a philosopher polymath at Cambridge University, introduced it. Although the existence of now-extinct life forms was widely accepted, there was no understanding of the mechanisms for extinction. Humans were held to be a uniquely gifted form of life, though I have shown elsewhere that a single plant cell can detect stimuli similar to those we know through the classical five senses (sight, hearing, taste, smell and touch). Humans are optimized, but not unique.39

As knowledge expanded, the evidence unearthed by geologists was still interpreted in biblical terms. Gravel beds, for instance, simply proved the flood as described in the Old Testament. There was no formal association for oryctologists (as fossil enthusiasts were still known), and most of the fossils in collections were shells and isolated vertebræ. Most wealthy collectors purchased their specimens. Although they enjoyed wandering out and about in nature, picking up items of interest, most lacked the acute levels of perception to identify what was important. Naturalists know that a collector must ‘get their eye in’, and most fossil enthusiasts were armchair amateurs who found it easier just to buy what they could.

The science of geology was given a boost by the work of an uneducated genius, the son of an Oxfordshire blacksmith. This was William Smith, who became a surveyor and worked on the construction of canals and coal mines across the country. This is when he noticed how the same strata cropped up in disparate parts of Britain, and eventually he collected all his observations together to create the first geological map of the whole of Britain. Because he was of working-class origins he was widely dismissed by educated society; he spent time in a debtor’s prison and his work was extensively plagiarized. Eventually, however, his conclusions were published in 1815 as a vast and detailed map, 8 feet 6 inches (2.6 metres) long, the first detailed geological map of an entire country produced anywhere. It was an astonishing achievement. Smith’s conviction that rocks could be systematically studied arose from his awareness of the increasing interest in fossils. Whereas most people regarded them as objects of curiosity, Smith saw them as indicators of a hidden reality – the key to unravelling the strata on which Britain was built. Smith had clear sight and a methodical mind, and created lyrical literature. In 1796, he wrote this prescient prose:

Fossils have been long studied as great curiosities, collected with great pains, treasured with great care and at a great expense, and shown and admired with as much pleasure as a child’s hobby-horse is shown and admired by himself and his playfellows, because it is pretty; and this has been done by thousands who have never paid the least regard to that wonderful order and regularity with which nature has disposed of these singular productions, and assigned to each class its peculiar stratum.

The first geological map of Britain was published by William Smith, a self-educated surveyor, in 1815. It was over 8 feet (2.6 metres) long and was based on an outline map by John Cary. This was the first geological map to cover such a large area.

Smith fell into debt whan an agreement to provide stone for a customer could not be fulfilled. He raised £700 by selling his fossil collection to the British Museum but was confined in the debtor’s prison for the remaining £300. After his release in 1819 he worked as surveyor for Sir John Johnstone, who soon appointed him land steward to the family estate in Hackness near Scarborough. Johnstone was astonished at Smith’s knowledge, and encouraged him to design the Rotunda, a display of the geology of the Yorkshire coast with strata all shown in their correct order in curved cases. This remarkable building survives to the present day, and is the oldest geological museum anywhere in the world.

Gideon Mantell was also conversant with Smith’s map, and Mantell entered into deep discussions with others interested in rocks. For instance, he became friendly with a mining engineer named John Hawkins who was similarly interested in the strata that surrounded them. Other friends were George Bellas Greenough, who was working towards his own map of Britain’s rocky strata, and James Sowerby, who encouraged the young Mantell to publish a book that would extend and refine the results for Sussex published in William Smith’s pioneering map.