Полная версия

Too Big to Walk

In America, the ‘Ohio Animal’ had continued to attract interest, and in 1796 Thomas Jefferson (who became the president of the United States just five years later) sent a small expedition to look for extinct mastodons and mammoths near the Ohio River in Kentucky. Like most well-educated statesmen of his time, Jefferson liked to keep abreast of discoveries in natural history and science. Indeed, when the White House was first built, it was furnished with a ‘Mastodon Room’ to house fossil collections. In 1797, Jefferson gave a presentation at the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia, describing a fossilized giant sloth that now bears his name: Megalonyx jeffersonii. When the presentation was printed as an academic paper in the Society’s journal, it became one of the first American publications in the developing field of palæontology.20 More recent American presidents are perhaps less likely to publish academic papers in scholarly journals.

Dinosaur footprints were now being discovered by new arrivals in the United States. The first we know about were unearthed in 1802 by a farm boy named Pliny Moody of South Hadley, Massachusetts. Moody dug up a slab of red sandstone while ploughing. It showed some small, sharp, clear, three-toed footprints. This fine specimen was fixed above the farmhouse door, where a local physician confidently identified them as being the tracks of Noah’s raven. The story of the biblical flood was still the conventional explanation at the time, because there was no understanding of fossil footprints left by dinosaurs, so although it seems fanciful to us, this was a popular diagnosis at the time. We are quick to ridicule such early conventions, though a glance at today’s religious television channels reminds us that present-day beliefs can be as superstitious and fanciful as anything we have seen in the past.

The Napoleonic Wars had been raging in Europe and they finally ended in 1815, whereupon Georges Cuvier seized the opportunity to visit England. One of his first ports of call was to meet William Buckland in Oxford. Buckland was born on March 12, 1784, in Axminster, Devon, and spent much of his time as a child walking across the countryside with his father, the Rector of Templeton and Trusham. His father used to show him how to collect fossilized shells, including ammonites, from the strata of Jurassic Lias that were exposed in the quarries. The young Buckland went to school in Tiverton, and eventually entered Corpus Christi College at Oxford University, to study for the ministry. He regularly attended lectures on anatomy given by Christopher Pegge, a physician at the Radcliffe Infirmary in Oxford, and he was particularly intrigued by part of a fossilized jawbone that Pegge had purchased for 10s 6d (now about £40 or $55) in October 1797. Buckland also went to the presentations given by John Kidd, Reader in Chemistry at Oxford, on subjects ranging from inorganic chemistry to mineralogy, and discovered that Kidd had himself collected several fragments of huge bones from the Stonesfield Quarry near Witney, some 10 miles (16 km) away. The plot was thickening.

Buckland meanwhile continued searching for fossil shells in his spare time. These he initially took as evidence of the biblical story of the flood, but as the years went by he turned towards more scientific reasoning and abandoned the literal truth of the Old Testament. After graduating, he was made a Fellow of Corpus Christi College, Oxford, in 1809, and he was formally ordained as a church minister. In 1813 Buckland was given the post of Reader in Mineralogy, following John Kidd, and his dynamic and popular lectures began to include a growing emphasis on palæontology. By now he was becoming an experienced collector, and in 1816 he travelled widely in Europe, including Austria, France, Germany, Italy, Poland and Switzerland. He visited Cuvier on several occasions.

Buckland became something of an eccentric. He always wore an academic gown instead of overalls for his fieldwork and claimed to have devoured his way through most of the animal kingdom, serving mice, crocodiles and lions to his guests (and he claimed that the two foods he disliked most were moles and houseflies). On his travels, he was said to have been shown the preserved heart of King Louis XIV nestling in a silver casket and remarked: ‘I have eaten many strange things, but have never eaten the heart of a king before,’ and so he picked it up and bit into it before anybody could stop him.

Buckland’s first major prehistoric discovery was not of a reptile, but a human – the Red Lady of Paviland, a human skeleton found in South Wales. He decided to explore the largely inaccessible Paviland cave on January 18, 1823, only to find this well-preserved skeleton, which he initially took to be the corpse of a local prostitute. He later concluded that the body had been placed there by early residents in pre-Roman times, though more recent tests have shown that it dates back 33,000 years – indeed, it is now accepted as the most ancient human skeleton ever found in Britain. Buckland married an enthusiastic fossil collector and accomplished artist, Mary Morland, in 1825, and thereafter Mary devoted herself to illustrating her husband’s palæontological publications with flair and skill.

By the time of Cuvier’s visit, Buckland was studying fossil collections, and among the specimens he showed to his French visitor were the Scrotum humanum and Pegge’s curious specimen of a fossilized jawbone. Cuvier concluded that these were both fragments from gigantic reptiles. William Conybeare, a palæontologist colleague of Buckland’s, referred to these specimens as the remains of a ‘huge lizard’ for the first time in 1821, and the physician and fossil hunter James Parkinson soon announced his intention to call the creature Megalosaurus from the Greek μέγας (megas, large). Parkinson estimated that this had been a huge land animal measuring 40 feet long and 8 feet tall (12 x 2.5 metres). Parkinson is little known today as a palæontologist, though we all know his name in a different context – he is the physician who correctly identified the degenerative disease known, in his time, as a ‘shaking palsy’ and which we now call Parkinsonism. Most palæontologists at the time were physicians, and many made discoveries that resonate beyond the world of the fossil collector.

Buckland now faced urgent demands from Cuvier for details to include in his own book, and meanwhile Buckland continued to investigate the fossil remains, while his wife Mary began preparing the detailed drawings of the remains for publication that were to be the basis of the published lithographic plates. Buckland had met Mary while travelling by horse-drawn coach in the West Country. An account records:

Both were travelling in Dorsetshire and each were reading a new and weighty tome by the French naturalist Georges Cuvier. They got into conversation, the drift of which was so peculiar that Dr. Buckland exclaimed, ‘You must be Miss Morland, to whom I am about to deliver a letter of introduction.’ He was right, and she soon became Mrs Buckland. She is an admirable fossil geologist, and makes midels in leather of some of the rare discoveries.21

They worked together diligently in every spare moment they could find. There was now growing interest in the fossils being found at Lyme Regis on the Dorset coast of southern England. Most people believed these rocky remains to be the fossils of familiar fauna (crocodiles or dolphins). Collectors including Henry de la Beche and William Conybeare carefully examined a range of specimens, and published a joint account in 1821 concluding that they might represent something very different – a new kind of reptile. They mentioned the work of a host of amateur collectors, acknowledging ‘Col. Birch, Mr. Bright, Dr. Dyer, Messrs. Miller, Johnson, Braikenridge, Cumberland, and Page of Bristol,’ and they now concluded that this new type of reptile formed a bridge between ichthyosaurs and crocodiles, and so they coined a new term for these creatures: plesiosaurs.22

Interest in the fossil reptiles started to spread, and in 1822 James Parkinson published a book on his investigations entitled Outlines of Oryctology, which, although primarily concerned with seashells and other familiar fossils, also reported the latest investigations of the huge reptile fossils that were now beginning to appear. In this book, Megalosaurus was included as ‘an animal, approaching the monitor [lizard] in its mode of dentition, &c., and not yet described,’ while Mosasaurus was defined as ‘The saurus of the Meuse, the Maestricht animal of Cuvier.’ Parkinson reported that Cuvier and others placed this reptile ‘between the Monitors and the Iguanas. But, as is observed by Cuvier, how enormous is its size compared with all known Monitors and Iguanas. None of these has a head larger than five inches; and that of this fossil animal approaches to four feet.’ Suddenly there was a glimpse of the future – the notion of gigantic prehistoric reptiles was began to emerge.23

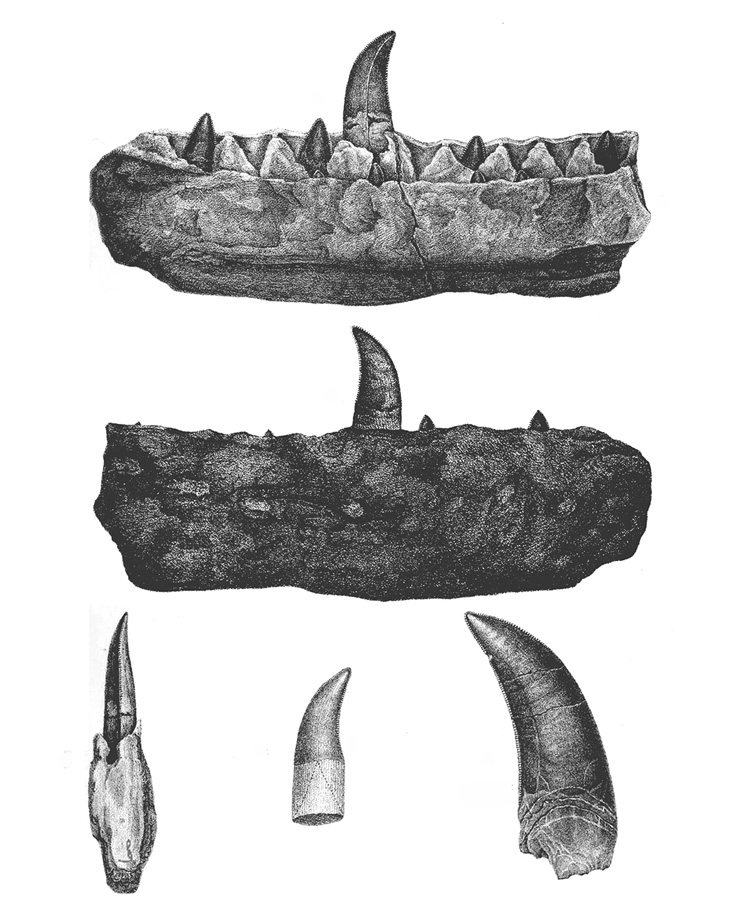

The Bucklands had by this time assembled a range of fossils carved out from the Stonesfield strata, including a length of lower jaw with a single tooth, a dorsal and an anterior caudal vertebra, five fused sacral vertebræ, two ribs and several sections of the pelvis. Clearly, these did not all come from the same animal, and Buckland’s interpretation of some of the bones was incorrect (he thought the ischium was a clavicle). Mary provided perfectly precise pictures of the specimens for the lithographer, and on February 20, 1824, at a meeting of the Geological Society of London, Buckland formally announced the discovery of a new monster reptile bearing the name bestowed upon it by James Parkinson: Megalosaurus.24

William Buckland asked his wife Mary to prepare these exquisitely detailed drawings of the jawbone found in the Stonesfield quarry, and in February 1824 he announced the name James Parkinson had suggested for this dinosaur: Megalosaurus.

With James Parkinson’s pioneering report, and now with William Buckland’s formal paper, the world’s first dinosaur was formally revealed to the world. It had taken almost 150 years for the true nature of the Scrotum humanum specimen to be recognized. No, it was not an ancient gentleman’s family jewels, but a monster’s elbow. What an extraordinary revelation!25

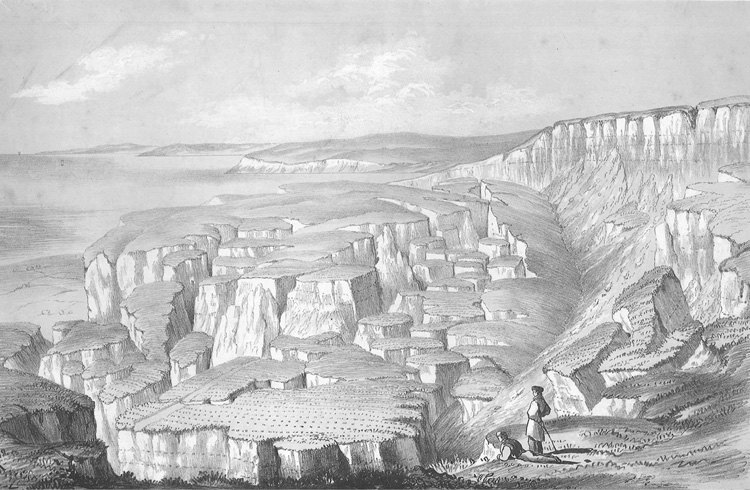

Lyme Regis, a coastal village in the English county of Dorset, was emerging as a centre for the study of fossils. The most prominent of the collectors was Richard Anning, a cabinetmaker who had settled in Blandford Forum and married a local girl, Mary Moore (popularly known as Molly), on August 8, 1793. They moved to Lyme and built a house for themselves by the bridge over the River Lym. Storms sometimes struck that shore, roaring in from the Atlantic and devastating the beach. The Annings’ home was flooded more than once; on one stormy night it was said that they had to climb out of an upstairs window to escape the rising tide. On Christmas night, 1839, the entire family almost lost their lives. It was after midnight, with everyone in bed and asleep, when there was a mighty roar and the ground suddenly shuddered as a huge slice of the cliff slid into the sea. Witnesses next day said there was a vast chasm where the land had split open for more than half a mile (about 1 km), and a cliff-top field belonging to a farmer slid down 50 feet (about 15 metres) towards the sea. The Bucklands were staying nearby at that time, and Mary used her considerable artistic talents to capture the scene for posterity. Next morning, Boxing Day, the beach and the shattered cliff top were thronged by visitors, eager to see the catastrophic collapse. The landslip caused a huge reef to appear in the sea, towering 40 feet (about 12 metres) tall and enclosing a lagoon at least 25 feet (8 metres) in depth. Within weeks, all this had washed away, and the beach had returned to normal.

Richard and Molly Anning had 10 children. Their first was Mary, who was born in 1794, but tragically died in a fire. The Bath Chronicle newspaper recorded the incident: ‘A child, four years of age of Mr. R. Anning, a cabinetmaker of Lyme, was left by the mother for about five minutes in a room where there were some shavings … The girl’s clothes caught fire and she was so dreadfully burnt as to cause her death.’ It seems she was trying to rekindle the fire with the slivers of wood.26

In December 1839, Mary Buckland drew the great landslip near Lyme Regis. It was engraved on zinc by George Scharf and printed as a hand-tinted lithograph by Charles Joseph Hullmandel, who studied chemistry under Michael Faraday. (Reproduced by permission of the Geological Society of London)

The distraught parents named their next baby girl Mary in memory of their lost child – and this little girl was destined to become the greatest of all the pioneer fossil hunters. Of the remaining children, only one other, a son named Joseph, survived to adulthood. Infant mortality through this period was around 50 per cent, so the loss of so many infants would not have been regarded as particularly unusual. People at that time lived so close to tragedy. Death was simply a shade of daily life.27

The rocky strata near Lyme Regis are marked by numerous layers of Blue Lias, a rock rich in mudstone that was originally the bed of a shallow sea. This form of rock is widely spread across southern England and South Wales and was laid down in late Triassic and early Jurassic times between 195 and 200 million years ago; it is also known as Lower Lias. The muddy seabed was littered with ammonite shells, and the remains of sea creatures – fish and swimming reptiles – are also abundant. Both youngsters accompanied their parents scouring the rocky shelves exposed after a storm, and they quickly became adept at finding fossils. Then, in 1810, their father Richard Anning suddenly died, and the family was left in penury. Their only possible source of income was now fossil hunting, and the children went out with their mother each day, looking for fossils to sell as souvenirs to visitors. They sold, as they do today, for a present-day value of about £10 ($12). When he was 15, young Joseph discovered part of a remarkably well-preserved ichthyosaur in a rocky shelf and showed his sister where it lay. A year later it was more fully exposed, and Mary had the skill to extricate it from the shore. The skeleton was well preserved, though at the time they could find no skull. Those who saw it concluded that it was some sort of crocodile. Ever since John Walcott’s published descriptions in 1779, others had been finding similar specimens. The Blue Lias rock is visible along the coast of South Wales, and as a student I used to find fragments of ichthyosaur skeletons in the smooth strata that storms had exposed. At Welsh St. Donats in 1804, an enthusiast named Edward Donovan discovered an ichthyosaur specimen represented by its jaw, vertebræ, ribs and pectoral girdle. It would have measured 13 feet (4 metres) long and was adjudged to be a gigantic lizard. In the next year two more were found in the same strata on the opposite side of the Bristol Channel, one discovered at Weston by Jacob Wilkinson and the other by the Reverend Peter Hawker. This specimen soon became known as Hawker’s Crocodile. In 1810 an ichthyosaur jaw was dug out at Stratford-upon-Avon, but the locals simply put it with some bones from a fossilized plesiosaur to make up a specimen that was more marketable. The name ichthyosaur was becoming popular, derived from the Greek ιχθυς (ichthys, meaning fish) and σαυρος (sauros, lizard).

By 1811 the time was ripe for a major discovery: in Lyme Regis, along what is now called the Jurassic Coast of Dorset, the first complete ichthyosaur skull was found by Joseph Anning, the brother of Mary, and she soon found the thoracic skeleton of the same animal. Their mother Molly sold the whole piece to Squire Henry Henley for £23 (now about £1,300 or $1,600) and it was later bought by the British Museum for twice the price. It remains on display at the Natural History Museum and is now identified as a specimen of Temnodontosaurus platyodon. Both the young Mary and her mother were now adept fossil hunters, while Joseph went on to train as a furniture upholsterer. It was the sight of the young Mary Anning that visitors found so unusual. She did not just collect, but she studied the remains that she found, transcribing lengthy accounts from learned texts and meticulously copying the illustrations of fossils they contained.

By now, Buckland was regularly visiting Dorset to purchase fossils and collect his own specimens, and he became particularly intrigued by the ‘bezoar stones’ that Mary Anning had been discovering alongside her ichthyosaur skeletons. The bezoar was the name given to an indigestible mass found within human intestines; it was believed that a glass of poison containing a bezoar would be instantly rendered harmless. The word comes from the Persian pādzahr (پادزهر), meaning ‘antidote’. Anning discovered that, when those rounded, rough stones were broken open, they always contained the scales and bones of fish and smaller ichthyosaurs. In 1829, Buckland recognized that these stones were present everywhere that fossil reptiles were found, and he suddenly realized what they were. They were fossilized faeces. They really were masses from within the gut. Buckland decided to call them ‘coprolites’, the term we use to this day. He became devoted to the study of the fossils that Mary Anning had discovered, and his enthusiasms gave rise to an historic painting by Henry de la Beche entitled Duria Antiquior – a more Ancient Dorset, which portrayed some of the swimming reptiles Mary Anning had discovered, with some of Cuvier’s pterodactyls swooping across the heavens. At last it was becoming clear that there had been an age of strange reptiles that were frighteningly large and had bizarre lifestyles. The age of the dinosaur was steadily coming closer.

A prominent British geologist, Sir Henry Thomas de la Beche, born in London in 1796, had moved to Lyme Regis where he befriended Mary Anning. He investigated fossil reptiles and wrote extensively on surveying rocky strata. De la Beche was by this time known as one of the most prolific of geologists, and his published works range from the description of fossil marine reptiles to the study of British stratigraphy. He also wrote learned textbooks dealing with the application of geological survey methods. However, he became best known by the public for his talent as a cartoonist. In one of them he satirizes the likes of Buckland and Lyell. This cartoon appeared in 1830, the same year in which Lyell’s great, ground-breaking formal book on geology was published in London. In this mighty work Lyell discussed stratigraphy, dealt with the value to commerce of systematic prospecting, arguing that the forces that were acting in nature today were the same as those that had acted in the past, and asserted that they would be the same in the future (the theory that pretentiously became known as uniformitarianism). When Charles Darwin set off on his voyage aboard HMS Beagle in 1831, it was Lyell’s new book that accompanied him on his geological expeditions.28

In 1830 Henry de la Beche, the first director of the Geological Survey of Great Britain, painted this historic watercolour representation of prehistoric life based on Mary Anning’s discoveries. He entitled it: Duria Antiquior – A more Ancient Dorset.

The French fossils that Cuvier had dismissed as being from a crocodile had meanwhile yet to be properly identified. In June 1793, a zoologist named Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire had become one of the first 12 professors at the newly opened Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris. His principle concern was setting up a zoo, but the following year he had struck up a relationship with Cuvier and they published several joint papers on the classification of animals. Fossils were also discussed. In 1807 Saint-Hilaire was elected to the French Academy of Sciences and concentrated thereafter on the study of the anatomy of invertebrates, corresponding at length with his British friend Robert Edmund Grant. His assistant, a young undergraduate who was particularly interested in barnacles, was a medical school drop-out named Darwin – Charles Darwin. Saint-Hilaire was concerned that Cuvier had too hastily concluded that Streptospondylus was a crocodile, and so he examined the fossils again. He decided that they belonged to two species of extinct reptile, and named them Steneosaurus rostromajor and S. rostrominor. In England, Megalosaurus was already officially recognized as a genus, though it still had no species name. It was a German palæontologist, Ferdinand von Ritgen, who gave it the provisional name Megalosaurus in 1826. He called the species Megalosaurus conybeari, though this name was never formally adopted.29

In 1827 Gideon Mantell resolved to include this fossil animal in his geological survey of south-eastern England and felt it appropriate to name it in honour of Buckland. It has been known as Megalosaurus bucklandii ever since. This was a crucial step in the history of science: it was the first dinosaur name formally to enter the literature of science. Suddenly, dinosaurs were real.30

These new areas of investigation were now attracting increasing attention. The Geological Society of London was inaugurated on November 13, 1807, at the Freemasons Tavern in Great Queen Street, and Buckland was elected their president in 1824–1825 and again in 1840–1841. He had been elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1818 and became a member of their Council from 1827 to 1849. Buckland’s interest in spreading the word led to his involvement in the newly formed British Association for the Advancement of Science, and in 1832 he was appointed their president and chaired the second conference. By now, Buckland was riding high.

The limestone and chalk quarries at Maastricht continued to provide specimens for collectors, and indeed the final 6 million years of the Cretaceous are known to this day as the Maastrichtian epoch. In spite of his studies of fossil mammals – including extinct species, like mammoths – Cuvier steadfastly refused to accept the concept of evolution. To him, species were immutable, and he substantiated this notion by comparing mummified cats and dogs from ancient Egypt and showing that these creatures were unaltered when compared with present-day specimens. Frozen carcasses of woolly mammoths had first been excavated by explorers in the 1690s, and the first scientifically documented example was discovered in the mouth of the River Lena, Siberia, by a Siberian hunter named Ossip Schumachov in 1799.31

Schumachov saw these carcasses as a viable source of tusks that he could sell on to ivory traders, but Johann Friedrich Adam, a Russian explorer who later changed his forename to Michael, went at once to inspect the newly discovered frozen carcass. He found that much had already been devoured by wolves. Even so, it provided the most complete mammoth skeleton ever found and was assembled at the Zoological Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences, where it was mounted alongside a skeleton of an Indian elephant.

This substantiated that animals could become extinct and that skeletons of preserved carcasses were similar to the fossilized remains that were excavated elsewhere. Cuvier documented his fossil skeletons, and in 1812 he published his research, serving to dignify the study of fossils. The Maastricht fossil was a lizard as big as a crocodile, and the pterodactyl he distinguished from birds or bats, insisting it was a flying reptile. These were exciting conclusions that were already causing consternation and interest among scientists and writers. It was now clear that there had been eras when strange and unfamiliar creatures roamed the Earth32 and in Bleak House, which Charles Dickens started writing in 1852, he said it would be ‘wonderful to meet a Megalosaurus, forty feet long or so, waddling like an elephantine lizard up Holborn Hill.’