Полная версия

Too Big to Walk

Just as we imagine that Richard Owen gave us dinosaurs, we have been taught to hero-worship Charles Darwin as the originator of evolutionary theory. Yet we can now see that evolution was far from being Charles’ original idea. Not only had it been summarized by his own grandfather in a previous century, but the essential notion of natural selection was omitted from his early accounts of evolutionary mechanisms, even though it had been published decades earlier by an experimenter whose work Darwin knew. Today, we know Charles Darwin for the crucial concept ‘survival of the fittest’, and most authorities say that the theory is Darwin’s own – yet ‘survival of the fittest’ was not even his phrase. It was coined by Herbert Spencer in his own book on biology. Wrote Spencer: ‘Survival of the fittest, which I have here sought to express in mechanical terms, is that which Mr. Darwin has called ‘natural selection’, or the preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life.’11

So you can see that evolution by natural selection was thought up long before Darwin began to write about it, and his most famous phrase – survival of the fittest – was coined by somebody else. Indeed the phrase did not enter Darwin’s own writings until the Origin of Species appeared in its fifth edition. Even by this time, he had not mentioned the word ‘evolution’ to describe his views, for that term did not appear until the Origin of Species was in its sixth edition.

Belief in Darwinian evolution has since become an academic requirement. The question: ‘Are you, or are you not, a Darwinist?’ is used to mark out real biologists from those beyond the pale. It is rich in resonances of Senator Joseph McCarthy and the famous question: ‘Are you now, or have you ever been, a member of the Communist Party?’ If you don’t espouse Darwinism, then the biological establishment won’t want you. Yet we have now seen that Charles Darwin didn’t discover evolution. He was not the first to introduce the idea of ‘natural selection’, and he wasn’t even the HMS Beagle’s naturalist. When it came to evolution, Charles Darwin was a latecomer on the scientific scene – during his lifetime his book on earthworms outsold the volume on evolution. Modern-day science likes to worship remote figureheads; but much of this tendency is simply science’s cult of celebrity. Don’t be taken in.

It is clear that the person who triggered Darwin’s interests in evolution was a brilliant young explorer named Alfred Russel Wallace. Wallace worked as a watchmaker, a surveyor and then a school teacher before setting out to explore the Amazon in 1848. His intention was to collect specimens for commercial sale to collectors back in Britain, but his ship was destroyed by fire on the way home to England and all the collections went up in flames. You might think that this costly disaster would have ended his career, but Wallace had been fully insured. He claimed for the value of the lost specimens and suddenly was wealthy, without the need to sell everything that he had discovered. With the proceeds safely in his bank, he wrote up his findings on palm trees and on monkeys, and set off again, exploring and collecting in Southeast Asia.

While staying on Borneo, Wallace wrote a paper ‘On the Law which has Regulated the Introduction of Species’ that was published in the Annals and Magazine of Natural History in September 1855. He asserted that ‘Every species has come into existence coincident both in space and time with a closely allied species’ and noted (as he had done in a book he had written on the Amazon monkeys) that geographical separation seemed to lead to species becoming distinct, a finding that Darwin confirmed with his observations of the Galápagos finches. Wallace then wrote another great paper entitled ‘On the Tendency of Varieties to Depart Indefinitely from the Original Type’. Before seeking a publisher, he mailed it to Darwin to ask for his scholarly opinion. Darwin received it on June 18, 1858 and realized that here, set down in writing in detail, was a theory of evolution by natural selection. There was nothing new in the idea. Remember, it had been casually circulating for centuries and the concept had been part of the vernacular currency of biological science since Erasmus Darwin’s publications of 1784. For decades, Charles Darwin (along with so many others) had assumed that evolution proceeded through natural selection, and now Wallace had set it out formally in a scientific paper. Evolution had been studied by Wallace as a mechanism operating among wild organisms in nature, whereas Darwin had mostly studied artificial breeding by farmers and horticulturists. This was a suitable time for the theory to be discussed, and Alfred Russel Wallace was the man who triggered the debate. Darwin decided to discuss the paper with his friends. Some of his circle were professional men of science, like Joseph Dalton Hooker; others were struggling to find a position, including Thomas Henry Huxley who had won the gold medal of the Royal Society but still could not find employment. Huxley wrote at the time: ‘Science in England does everything but pay. You may earn praise, but not pudding.’12

Darwin was also acquainted with a range of independent-minded investigators, including John Tyndall, who was a self-taught physicist; Thomas Hirst, an amateur mathematician; Edwin Lankester, a builder’s son who taught himself medical biology; and Arthur Henfrey, who had qualified in medicine but became prominent as a self-taught botanist. Darwin gathered some of these friends together to discuss how he should react to Wallace’s detailed article, and it was eventually agreed that a summary of Darwin’s ideas could be appended to a formal reading of Wallace’s paper. Darwin had set down a few thoughts in a letter to Hooker written in 1847, and there were more in a letter he had written to Asa Gray in 1857. These would make the basis of a submission. A suitable opportunity arose when the Linnean Society suddenly announced the date of a special meeting; there would be time for the reading of new research papers. The Society’s president, Robert Brown (the person who named the cell nucleus, and after whom Brownian Motion is named), had suddenly died, and July 1, 1858 was chosen as the date to elect a successor. Since there was time available for additional scientific presentations, it was agreed that the Honorary Secretary would read Wallace’s paper on evolution, followed by the extracts from Darwin’s letters on the subject. Neither Wallace nor Darwin was present. This launched the theory of evolution for discussion in the world of science, yet it did not catch anyone’s attention at the time. The new president of the Society thought it unimportant. In his annual report for 1858, he said that the year ‘had not been marked by any of those striking discoveries which at once revolutionize, so to speak, our department of science.’ That puts him in the same category as the A & R man at Decca who turned down The Beatles.

Today you can visit Charles Darwin’s house as a museum, just 9 miles (15 km) southeast of the Crystal Palace dinosaurs. The building is Down House, and it lies in the village of Downe. Today it looks just the same as it did when Charles Darwin lived there, with the rooms rich in original décor and authentic furnishings – but the back-story is very different. In 1907, the premises were sold and re-fitted to become Downe School for Girls. It remained so until 1922, when another girls’ school took over and ran until 1927. By this time, the rooms that Darwin used had all been stripped out, repainted in grey and converted into classrooms. The school building was then purchased in 1929 by a surgeon, Sir George Buckston Browne, with the idea of turning it into a museum. Down House was eventually acquired by English Heritage in 1996 and it reopened to the public after extensive refurbishment in April 1998. I have visited it many times and chaired meetings there. My friend Stephen Jay Gould flew over to speak at a conference I was organizing at the house. Original items from Darwin’s time have been returned over the years, and other items that are similar to the original furnishings have been purchased. Walking through the house today, it is hard to imagine it stripped bare and repainted as hordes of pubescent women tramped through its hallowed corridors for so many years – at that time, the interior was unrecognizable. The home now is a latter-day reconstruction, though the visitor may not easily discover the fact.13

Another frequent misconception is that Darwin was the official naturalist when he made his famous voyage in the Beagle. In a statement in the Origin of Species of 1859, Darwin claims to have ‘been on board HMS Beagle, as naturalist’. The implication is not correct. The ship already had an officially appointed naturalist, Robert McKormick, who also served as the ship’s doctor. Darwin was on board as the travelling companion of the ship’s master, Admiral Robert FitzRoy, the person who invented weather forecasts. He had invited Darwin because of his reading theology at Cambridge. FitzRoy was a fervent Christian, and hoped that Charles Darwin could utilize his knowledge to reconcile geology and biology to the teaching of the Bible. Darwin may have claimed to have been the ship’s naturalist in his later writings, but at the time he wrote that his appointment was ‘not a very regular affair’. We like to imagine that the Beagle was an explorers’ vessel on a civil voyage of discovery, but she was actually a Royal Navy warship: a Cherokee-class brig. This was a naval expedition, not a journey of discovery. And the captain had an ulterior motive; three captives had been brought to England from Tierra del Fuego; they had been taught English and trained as Christian missionaries. FitzRoy had taken on the major share of financing the voyage, because he wanted to return these men to the country of their birth where they could spread the word of God to this newly discovered land. The Navy organized the voyage on condition that FitzRoy meticulously surveyed the coast and the oceans around South America, so that precise navigational charts could be drawn up. Looking for new forms of life was nowhere in the plans.

The ship set sail on December 27, 1831. Darwin soon became absorbed by the many exotic life forms he encountered on that famous holiday. He was able to go ashore at will to collect and explore to his heart’s content. His adventures were comprehensively detailed in a book he wrote describing the voyage of the Beagle.14

He came to realize how coral atolls were formed, and he published a monograph entitled The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs. His adventures were many: in Chile he witnessed an earthquake. On the Galápagos Islands he dined on the flesh of the giant tortoises and later described how the different shapes of their shells seemed to match the lifestyle imposed by the environmental situation of the different islands. The Galápagos finches, he concluded, were similar to those on the mainland but had clearly changed over time. He noted: ‘Such facts undermine the stability of species.’ He then changed it by adding one cautionary word: ‘Such facts would undermine the stability of species.’ There was no implication here that the presumed changeability of species was a novel concept, just that his observations substantiated the accepted view.15

The accessible style and exotic nature of the subject brought a wide readership, and suddenly Darwin had a new career – as an author of popular science. To me, his most visible legacy is his list of published books, which represent a remarkable devotion to making science accessible. They are all vividly written. Apart from the Origin of Species, he wrote on the geology of South America and on volcanic islands (1844), on the fertilization of orchids (1862), the movements of climbing plants (1865), the effects of cultivation on variation in plants and animals (1868), the Descent of Man (1871), insectivorous plants (1875), the effects of cross-fertilization in plants (1876), The Different Forms of Flowers on Plants of the Same Species (1877), and finally The Formation of Vegetable Mould through the Action of Worms, with Observations on their Habits (1881). This last title was a best-seller. Remember, Darwin’s book on worms sold far more copies during his lifetime than the Origin of Species.

Curiously, Charles Darwin showed no interest in dinosaurs. He is the person who popularized the theory of evolution, in which dinosaurs would play such an important part, but he did not include them in any of his books. How curious that Robert Darwin, who had presented the first scientific account of a fossil reptile in 1719, had been Charles’ great-grandfather. Since Charles’ grandfather Erasmus had also written about evolution, it is surprising that although Charles Darwin himself was fascinated by fossils, he had nothing to say about dinosaurs. Although the fact is little discussed these days, Charles Darwin was an expert with the microscope and he became interested in the microscopical structure of fossilized plants. He knew that they had been faithfully preserved in rock, but how much could you discern with the microscope? Was the cellular structure preserved?16

Darwin was not the first to speculate thus. As long ago as May 27, 1663, Robert Hooke at the Royal Society of London had looked at fossilized wood under his microscope. As we have seen (here), Hooke had carefully scrutinized his specimen of fossilized wood, and had worked out how it was formed, and he ascertained that the fossil sample showed the same structure as a specimen of fresh wood:

I found, that the grain, colour, and shape of the Wood, was exactly like this petrify’d substance; and with a Microscope, I found, that all those Microscopical pores, which in sappy or firm and sound Wood are fill’d with the natural or innate juices of those Vegetables, in that they were all empty, like those of Vegetables charr’d …17

By 1665 Hooke had recognized that fossil wood was similar to the structure of present-day plants. Darwin made the same observation, but he took it a stage further. Rather than simply inspecting the surface, he resolved to have the rocky fossils ground down with an abrasive paste to produce the thinnest of sections – so fine that light could shine through to reveal the inner structure. He had collected fossilized wood during his sojourn on HMS Beagle in 1834 when they called at the Isla Grande de Chiloé, midway along the coast of Chile. He noted at the time that he had found numerous specimens of ‘black lignite and silicified and pyritous wood, often embedded close together.’ Joseph Dalton Hooker, the founder of geographical botany and the director of Kew Gardens for 20 years, was a close friend of Darwin’s and he catalogued the specimens for the British Geological Survey in 1846. The collections were then lost for 165 years, until Howard Falcon-Lang, of the Department of Earth Sciences at Royal Holloway College of the University of London, investigated some drawers in a cabinet labelled ‘unregistered fossil plants’ in the vaults of the British Geological Survey near Nottingham. Falcon-Lang reported: ‘Inside the drawers were hundreds of beautiful glass slides made by polishing fossil plants into thin translucent sheets, a process [that] allows them to be studied under the microscope. Almost the first slide I picked up was labelled C. Darwin Esq.’ This remarkable discovery was a treasure trove, and all the slides have now been digitized and put online for public scrutiny.

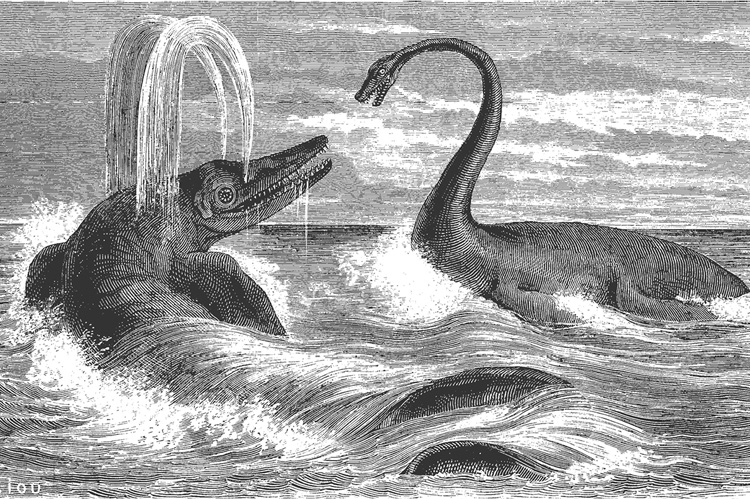

Stylised portrayals of an ichthyosaur and plesiosaur were published by Louis Figuier in La Terre avant le Déluge (the World before the Flood) in 1863. The drawing, by Édouard Riou, was engraved by Laurent Hotelin and Alexandre Hurel.

Given that the idea of evolution was fundamental to the understanding of dinosaurs in their temporal context, and that Darwin himself was an enthusiastic investigator of fossilized plants, it is surprising to me that he showed little interest in dinosaurs. Yet within two years of his book appearing, a discovery was made that seemed to provide the perfect example of evolutionary theory. This was the discovery in Germany of what seemed to be a creature halfway between reptile and bird – Archæopteryx. The skeletons and feathers have been excavated from the limestone quarries that surround Solnhofen, Germany. First to appear was a lone feather, found in 1860 by Christian Hermann von Meyer and now on display at the Humboldt Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin (see footnote here). Nobody can be certain it came from Archæopteryx, and it may belong to a similar (but different) genus, but the following year a skeleton was found in the same limestone at a quarry in Langenaltheim, 5 miles (8 km) west of Solnhofen. It was donated to a local physician, Karl Häberlein, in lieu of his professional fees. Knowing of the interest in palæontology then spreading across England, Häberlein sold it to the British Museum (Natural History) for the princely sum of £700 (today worth about £45,000 or $52,000). This has long been known as the London Specimen, and it is on display at the Natural History Museum to this day. The skeleton is mostly complete, though it lacks much of the skull and cervical vertebræ. In 1863 Richard Owen formally named it Archæopteryx macrura, admitting that it might not be the same species as the one from which the feather found by von Meyer had originated. Darwin was pleased by the find, for it fitted so well with the theories in his book. In the fourth edition, he added a note:

Now we know, on the authority of professor Owen, that a bird certainly lived during the deposition of the upper greensand; and still more recently, that strange bird, the Archæopteryx, with a long lizard-like tail, bearing a pair of feathers on each joint, and with its wings furnished with two free claws, has been discovered in the oolitic slates of Solnhofen. Hardly any recent discovery shows more forcibly than this how little we as yet know of the former inhabitants of the world.

It was many decades before further specimens of Archæopteryx were unearthed. The Eichstätt specimen was discovered in 1951 near Workerszell, Germany, and was not formally described until 1974, when details were published by Peter Wellnhofer. The fossil is on display at the Jura Museum in Eichstätt, Germany, and is of a curiously diminutive form. It has been suggested that it may be a different genus, and has been given the alternative name of Jurapteryx. The jury is still out on that. More typical of the type is the Maxberg specimen, which was discovered in Germany in 1956 and described in 1959. It was owned by a collector, Eduard Opitsch, who loaned it for exhibition in the Maxberg Museum in Solnhofen. When Opitsch died in 1991 and his estate was catalogued, that fine fossil had vanished. To this day, nobody knows what happened to it. Another fossil from Solnhofen, which had been discovered in 1972, was identified after being classified as an example of Compsognathus. This one too is the subject of debate, and some authorities want to classify it as Wellnhoferia, a cousin to Archæopteryx. A further example known as the Munich Specimen was unearthed in August 1992 by quarryman Jürgen Hüttinger who was working for the Solenhofer Aktien-Verein in the limestone quarries of Langenaltheim. Hüttinger duly reported his find to the quarry manager, who again called in Wellnhofer, the specialist palæontologist. The fossil was in fragments, and it was painstakingly reassembled in the State Paläontology Collection workshops. Only then was it realized that the skeleton was almost complete, apart from a single wing-tip. A methodical search through a ton of the nearby strata eventually brought it to light, and a near-perfect skeleton was the result. In April 1993, the finished specimen was formally presented to the press in Solnhofen, and it was put on public exhibition during the 150th anniversary of the Bavarian State Collection in Munich. It then went to the U.S. in 1997, where the Chicago Field Museum in Chicago displayed it as ‘Archæopteryx – the bird that rocked the world’, as part of the annual meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology. Eventually, it ended up in Munich’s Paläontologisches Museum, who paid 2 million Deutschmark for the fossil (now almost £1 million or $1.3 million).

Of all the specimens of Archæopteryx, this is the only one with a skull. It was found in 1874 by a farmer named Jakob Niemeyer, who sold it to an innkeeper, Johann Dörr, to decorate his bar. It is now in the Museum für Naturkunde, Berlin.

The best specimen of them all has a mysterious beginning. It was the property of a collector in Switzerland, whose wife – after his death in 2001 – offered it for sale to the Senckenberg Museum in Frankfurt, Germany. They lacked the funds to purchase it until Burkhard Pohl, who founded the Wyoming Dinosaur Center (WDC) in Thermopolis, put them in contact with an anonymous benefactor who came up with the funds. It was put on public display in Frankfurt, and then in 2007 was transferred to Wyoming. German palæontologists were horrified, and began a protest petition. Although no law had been broken by the export of the fossil, it would be unavailable for easy access by German investigators, and would also be passing from a state museum in Frankfurt to a privately owned collection in Wyoming. The directors of the WDC formally issued a statement, saying that the specimen would at all times be freely available for scholarship and study, which mollified the protestors and peace was resumed. This, now known as the Thermopolis Specimen, shows a perfectly preserved skeleton and has been expertly curated. It also retains voluminous sprays of feathers on the body and the wings, and is believed to be the most vivid and perfectly preserved of them all. It has become a key item of evidence in the continuing debate about whether Archæopteryx was truly the first bird or was closer to the dinosaur end of the evolutionary spectrum. It was described in 2005 as having ‘theropod features’ because of the angle of one of its toes; mentioning a connection with meat-eating dinosaurs is a great way to attract maximum attention. Yet nobody knows where it was originally found.18

This specimen was subsequently named Archæopteryx siemensii, and it is not only the best of them all, but is the only one on display outside Europe. It resides in America, and in that sense it is unique.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.