Полная версия

Too Big to Walk

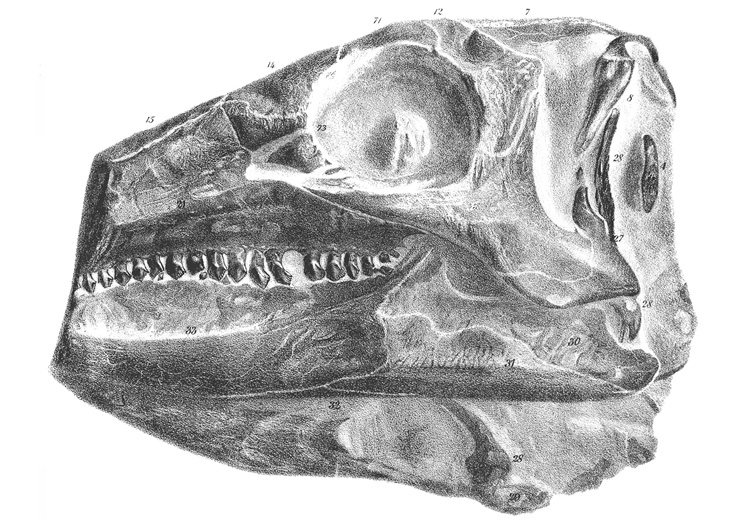

James Harrison, a Dorset quarry manager, discovered this skull of Scelidosaurus harrisonii after it was excavated in mudstone destined for the cement furnace. It was purchased by Henry Norris and published by the Palæontological Society in 1861.

Harrison later retrieved a portion of the tibia and fibula of this creature, then a claw, and finally a skull, which Owen formally described in 1861, naming this species Scelidosaurus harrisonii in honour of its discoverer. When the rest of the dinosaur had been excavated, it revealed a surprisingly complete skeleton. Although the tip of the animal’s snout was missing, the skull and jaws were intact, and the pelvis, ribs, hindlimbs and most of the vertebræ were retrieved. Of the forelimbs (and the end of the tail) there was no sign, but otherwise it was an incredible find. The body of Scelidosaurus measured about 13 feet (4 metres) long and was covered with a protective shield of bony scales or scutes, hundreds of which had survived, with many still in roughly the original position. This was the most complete dinosaur skeleton ever found, yet Owen carried out hardly any further investigation. This dinosaur was later described by the prominent American palæontologist Othniel Marsh, who erroneously assumed it had long legs, but not until the 1960s was it further investigated. Acid treatment was used to help release the scutes from their stony matrix, but the entire fossil has yet to be completely recovered. After nearly 160 years, this fascinating fossil is still waiting to be fully described.

These are stories with endless fascination, and they have attracted the attention of innumerable authors and even some movie producers. In 2002 the story of the pioneering British work on dinosaurs became the subject of a television movie produced by National Geographic, The Dinosaur Hunters. Henry Ian Cusick played Gideon Mantell and Rachel Shelley played his wife Mary. Alan Cox was Richard Owen, Michelle Bunyan his wife Caroline; Mary Anning was portrayed by Rebecca McClay and William Buckland by Michael Pennington. The movie was well received and remains available online.2

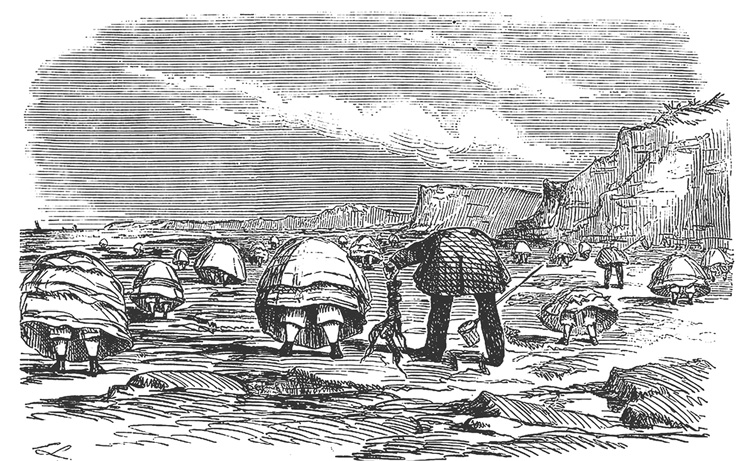

Beachcombers were now so abundant in England that they were sometimes teased for their eagerness. A cartoon for Punch magazine in 1858 showed a beach scene dotted with bizarre objects that look like barnacles; closer inspection shows they were day-trippers in petticoats, all bending over to search for fossils and seashells. That same year, William Dyce, a leading landscape painter, created his detailed picture Pegwell Bay, Kent – a Recollection of October 5th, 1858, which showed an autumnal beach scene with his family gathering specimens from the beach. Dyce was a student of geology and astronomy, and had painted the same bay before. This painting includes finely detailed studies of the chalky cliffs, while, high in the heavens, he captures the faint image of Donati’s comet to commemorate the widespread public interest in such phenomena. By this time, people were buying microscopes and telescopes as never before, and the popular understanding of science was burgeoning.

Searching for wildlife and fossils on the beach became such a popular pastime in Victorian England that cartoonist John Leech published this portrayal of beachcombers in Punch magazine in 1858. Their hooped skirts were reminiscent of giant barnacles.

While this excitement was spreading in Britain, new dinosaurs were being discovered in mainland Europe, and in 1859 a German physician and part-time palæontologist, Joseph Oberndorfer, acquired an exquisite little skeleton to add to his collection. He lived in the Riedenburg-Kelheim region of Bavaria, surrounded by quarries where a remarkably smooth and small-grained limestone was obtained. These layers had been laid down some 151 million years ago in a vast shallow lagoon, forming strata with so fine a grain that in 1798 a method was discovered for using the rock to produce flawless lithographic plates for printers. (To this day, lithographers speak of working ‘on the stone’ even though plastic and metal have long since replaced the German stone slabs.) From time to time, the local quarrymen used to find the remains of creatures trapped in the limestone, and the skeleton of a small dinosaur was perfectly preserved in the thin slab of rock that Oberndorfer obtained. He passed the fossil over to Johann A. Wagner, Professor of Zoology at the University of Munich, who had made extensive studies of mammalian fossils (including mammoths and mastodons) and who was delighted to be able to describe and name a new dinosaur. He decided to call it Compsognathus longipes from the Greek κομψός (kompsos, delicate) and γνάθος (gnathos, jawbone). The specific epithet longipes comes from the Latin longus (long) and pes (foot).3

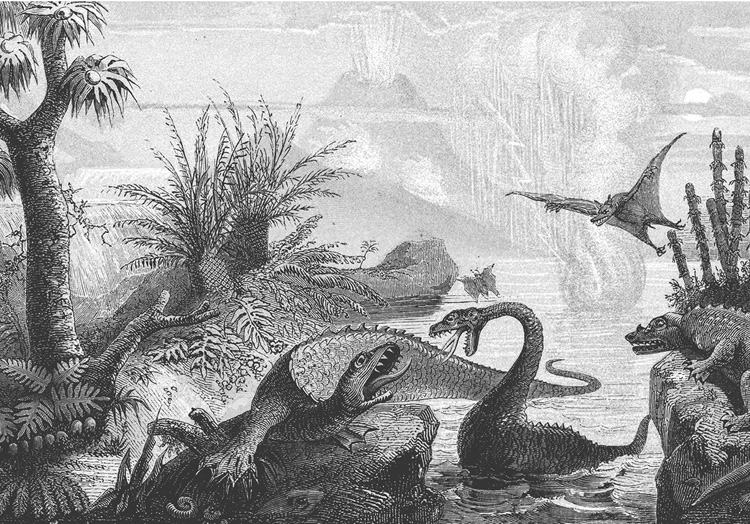

When W.F.A. Zimmerman published Le monde avant la creation de l’homme (The World Before the Creation of Man) in 1857, this engraving entitled ‘Primitive World’ by Adolphe-François Pannemaker was the frontispiece.

This was a momentous discovery, for it was the first complete skeleton of a carnivorous theropod dinosaur ever to be discovered, and it was also one of the smallest. It measures about 3 feet (90 cm) long and would have been the size of a swan. In 1865 Oberndorfer sold the specimen to the Bavarian State Institute for Paleontology and Historical Geology in Munich, where it is on display to this day. Curiously, we can still see its food: there is the skeleton of a small lizard still visible within the abdomen. When Othniel Marsh examined it in 1881 he concluded that it must have been an embryo within a female Compsognathus, though it was later accepted that it was the remains of a meal – lizards would have been a probable prey for a dinosaur like this. At the time, nobody realized that this was a raptor, in essence one of the tribe to which giants like Poekilopleuron and Megalosaurus belonged. Nothing more was found of this genus until 1971 when a second, somewhat larger, skeleton was retrieved from the lithographic limestone of Canjuers north of Draguignan, in Provence. This one measures 4 feet (125 cm) long and was quickly given a new species name Compsognathus corallestris, though this is almost certainly just a younger example of C. longipes. This second specimen was acquired in 1983 by the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris, where it is on public display. This diminutive dinosaur was interpreted as a fierce little hunter, and in 1997 its digital re-creation was given a prominent role in The Lost World: Jurassic Park.

An exquisitely preseved specimen of Compsognathus longipes, a small theropod the size of a goose, was published by Johann Andreas Wagner in 1861. It had been discovered in limestone deposits from Riedenburg-Kelheim in Bavaria.

In England, Owen was preoccupied with the foundation of a new museum to house all such specimens. He had succeeded in being appointed superintendent of the natural history collections at the British Museum in 1856, whereupon he announced his first mission would be to remove all the biological specimens, not just the dinosaurs, and install them in a new building of their own. One of his strongest supporters was Antonio Panizzi, the museum’s librarian, who had never liked the expansion of the museum into natural history, and was eager to see the specimens depart. Panizzi wanted the space. The campaign eventually succeeded, and in 1873 work began on the new museum in South Kensington that we know today. This was the British Museum (Natural History), and it opened in 1881. Not until 1963 did it become a museum in its own right; only since then has it been known as the Natural History Museum. Owen was appointed the first director of the new establishment, and a magnificent statue of him was erected in the main entrance hall. But it didn’t last; in 2009 it was summarily removed, only to be replaced by a statue of the single individual that Owen disliked most of all: Charles Darwin. It was the ultimate irony.

We celebrate the life of this man who coined the term ‘dinosaur’, Sir Richard Owen, founder of the Natural History Museum. He was a brilliant comparative anatomist but was regarded as arrogant, sadistic and deceitful by his peers.

Owen had always been a scientific anatomist, given to analysis and discipline, who saw no reason to modify his religious beliefs. Charles Darwin, on the other hand, was a collector and an ardent student of natural history. The publication of Darwin’s Origin of Species immediately made sense of dinosaurs. Science could now argue that there was a steady process of evolution, and there were innumerable extinct species that marked the various stages from the distant past. I have explained that, although we imagine that the study of dinosaurs began with Owen, in fact it dates back much further – and curiously, the same is true of evolution. We regard it as Darwin’s great revelation, but in fact the idea goes back to the ancients, and a clear understanding of natural selection was written by others, long before Charles Darwin happened on the scene. We celebrate Darwin as the originator of evolution, indeed ‘his’ theory is celebrated by everyone as a cornerstone of modern science, but he was not the first to come up with the idea. His pre-eminence in evolution is a myth that has fooled us all. The idea of evolution was understood by the Ancient Greeks; Empedocles wrote about it around 450 BC, as did Lucretius some three centuries later. Aristotle envisaged the progress of life as a Great Chain of Being around 350 years BC – so evolutionary ideas had been around for 2,000 years before Darwin’s time. Indeed, he was not even the first in his family to write on the subject. Charles Darwin had a distinguished grandfather named Erasmus who has been lovingly documented by my much-admired friend Desmond King-Hele, himself a distinguished physicist and a specialist on space research. In his spare time, King-Hele has written extensively on Erasmus Darwin, who was a leading physician. He wrote a great work on life entitled Zoonomia in two great volumes that embraced many subjects – including evolution. The book was published in 1794, and included these words:

Since the earth began to exist, perhaps millions of ages before the commencement of the history of mankind, would it be too bold to imagine, that all warm-blooded animals have arisen from one living filament, which the first great cause endued with animality, with the power of acquiring new parts, attended with new propensities, directed by irritations, sensations, volitions, and associations; and thus possessing the faculty of continuing to improve by its own inherent activity, and of delivering down those improvements by generation to its posterity.

There you have it: evolution in a nutshell. Erasmus went further, and even proposed survival of the fittest as the mechanism involved: ‘The strongest and most active animal should propagate the species, which should thence become improved,’ he wrote back in 1794. Here we have the nature of evolution spelled out decades before Charles began his work. The notion of ‘survival of the fittest’ was not even mentioned in the papers on evolution by Wallace and Darwin that were presented to the Linnean Society in 1858, yet here we can see that it had been spelled out by Charles’s grandfather more than 60 years earlier. When challenged, Charles conceded that he had of course read Zoonomia, but insisted that his grandfather’s ideas had ‘no influence’ on his own thoughts, which would be a remarkable example of selective amnesia. In fact, the concept of evolution by natural selection had been current for decades before he wrote his book, and some even predate Erasmus. A French explorer and philosopher named Pierre Louis Maupertuis had written about the idea in his book Vénus Physique (‘the earthly Venus’), published in 1745. Here it is in the original French:

Le hasard, dirait-on, avait produit une multitude innombrable d’individus; un petit nombre se trouvait construit de manière que les parties de l’animal pouvaient satisfaire à ses besoins; dans un autre infiniment plus grand, il n’y avait ni convenance, ni ordre: tous ces derniers ont péri.

In English, it reads:

Chance, you might say, produced an innumerable multitude of individuals; a small number found themselves constructed in such a manner that the parts of the animal were able to satisfy its needs; in another infinitely greater number, there was neither fitness nor order: all of these latter have perished.4

There we see ‘survival of the fittest’ spelled out unambiguously a century before Charles Darwin was active. It is clear from the words of Maupertuis that the idea of natural selection was known far earlier than it is popular to imagine, yet his work too has been largely forgotten. Desmond King-Hele has suggested to me that the disappearance of his work could be due to suppression by Voltaire, to whose lover Maupertuis taught mathematics. She was Gabrielle Émilie Le Tonnelier de Breteuil, the Marquise du Châtelet, and a brilliant mathematician who translated Isaac Newton’s Principia into French. Little wonder Voltaire regarded Maupertuis with envy.

Four years later the notion of evolution was spelled out by Georges Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, who was the greatest naturalist in France of his generation. He understood what fossils were, and he also recognized that living organisms changed over time, and that they came from simpler, common ancestors. Buffon’s books extended to numerous volumes and were highly detailed, while his grounding in practical science was exemplified by the engraving that acted as the opening illustration to the History of Animals – it shows him peering intently at a specimen down a microscope.5

As we have discovered, James Hutton was a brilliant geologist, and in 1794 he also came up with the essential idea of evolution by natural selection. In a far-reaching book on knowledge and reason, he wrote:

If an organized body is not in the situation and circumstances best adapted to its sustenance and propagation, then, in conceiving an indefinite variety among the individuals of that species, we must be assured, that, on the one hand, those which depart most from the best adapted constitution, will be the most liable to perish, while, on the other hand, those organized bodies, which most approach to the best constitution for the present circumstances, will be best adapted to continue, in preserving themselves and multiplying the individuals of their race.6

In the words ‘best adapted’ we have ‘survival of the fittest’ spelled out once more, long before Charles Darwin. Hutton’s thoughts might have gained even greater currency, but he had appalling handwriting and many correspondents had difficulty making out what he meant, so his followers relied only on his published works. Here is yet another quotation – still dating from the eighteenth century:

At length, a discovery was supposed to be made of primitive animalcula, or organic molecula, from which every kind of animal was formed; a shapeless, clumsy, microscopical object. This, by the natural tendency of original propagation to vary to protect the species, produced other better organized. These again produced other more perfect than themselves, till at last appeared the most complete of species, mankind, beyond whose perfection it is impossible for the work of generation to proceed.7

These words reiterate the concept of ‘survival of the fittest’ and were published in a book by Richard Joseph Sullivan in 1794.

This was the same year in which the farmer-cum-physician James Hutton published the idea of natural selection and Erasmus Darwin published Zoonomia, embracing similar thoughts. If there was truly a year when ‘survival of the fittest’ emerged in the literature of science as the principle driving evolution, then in my view it was 1794 – 65 years before Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species. His grandfather Erasmus revisited the topic of evolution in his poem entitled The Temple of Nature, published in 1802:

First forms minute, unseen by spheric glass,

Move on the mud, or pierce the watery mass;

These, as successive generations bloom,

New powers acquire, and larger limbs assume;

Whence countless groups of vegetation spring,

And breathing realms of fin and feet and wing.

Here are the notions that great eras had passed; ages of creatures living in water and aspiring to evolve on land had existed long before our present-day world emerged. By 1810 Jean-Baptiste Lamarck was publishing his views on evolution in France, and came up with a theory that was quickly rejected. Lamarck claimed that organisms evolved because of adaptations made in response to the experiences of successive generations – the reason a giraffe has a long neck, his theory argued, is because successive generations had stretched to reach up for leaves. Survival of the fittest, by contrast, holds that natural selection of longer-necked animals takes place as those with shorter necks were eliminated by an inability to reach up for leaves, and so they would die of starvation. We all know the two versions, and we have been taught to dismiss Lamarck and his views as misguided. Yet Charles Darwin did not do so – for him, the inheritance of acquired characteristics was entirely possible. This surprising view was called Pangenesis by Darwin, and he included many examples of the phenomenon in the last chapter of a book published in 1875 entitled Variation in Plants and Animals under Domestication. The argument was that cells within an organism would produce ‘gemmules’, microscopic particles containing inheritable information that accumulated in the germinal cells, which runs contrary to what is conventionally called Darwinian evolution. This is a remarkable revelation: in some ways, Darwin supported Lamarckism. More recent findings by biologists including Denis Noble at Oxford University have revealed the extent to which genetic change can be passed on through epigenetics – the way gene expression is regulated – so we now know that the extent to which genes are expressed can impose profound controls on evolution. Lamarck was partly right.

Although the theories expounded by Wallace and Darwin were to propose natural selection as an evolutionary principle, that essential idea had recently been published by an experimenter whose name has largely been forgotten. He was an arboriculturist named Patrick Matthew. Like Darwin, he went to Edinburgh University, and like Darwin, he left without a degree. Matthew returned to his family home in Errol, a small Scottish town, where he showed proficiency as a grower of fruit trees. He experimented with cross-breeding, and, notably, with grafting. These activities gave him insights into heredity, and in 1831 he published an important book entitled On Naval Timber and Arboriculture. It is in the Appendix that he introduced the crucial concept of natural selection. Wrote Matthew: ‘There is a law universal in nature, tending to render every reproductive being the best possibly suited to its condition,’ and he continued:

Nature, in all her modifications of life, has a power of increase far beyond what is needed to supply the place of what falls. Those individuals who possess not the requisite strength, swiftness, hardihood, or cunning, fall prematurely without reproducing … their place being occupied by the more perfect of their own kind.8

This was in print, and widely available, 27 years before Charles Darwin’s ideas were first presented. When the matter was raised with Darwin, he wrote: ‘I freely acknowledge that Mr. Matthew has anticipated by many years the explanation which I have offered on the origin of species under the name of natural selection,’ and he promised: ‘If another edition of my book is called for, I will insert a notice to the foregoing effect.’ He did not keep his word but wrote instead: ‘An obscure writer on forest trees clearly anticipated my views … though not a single person ever noticed the scattered passages in his book.’ In the fourth edition of the Origin of Species, Darwin eventually admitted:

In 1831, Mr. Patrick Matthew, published his work on Naval Timber and Arboriculture, in which he gives PRECISELY the same view of the origin of species as that … propounded by Mr. Wallace and myself in the Linnean Journal, and as that enlarged in the present volume.

He then added:

Unfortunately, the view was given by Mr. Matthew very briefly in scattered passages in an Appendix to a work on a different subject, so that it remained unnoticed until Mr. Matthew himself drew attention to it in the Gardeners’ Chronicle, on April 7th, 1860.9

This claim was disingenuous. Matthew’s views were well known and widely discussed when first they appeared – indeed, many libraries banned his book because of its scandalous allegations that evolution had occurred.

Since I have shown clearly that Charles Darwin was not the first to write a book on evolution, then who was? The first great book on the subject was Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation, published in 1844 and written in great secrecy by an anonymous naturalist, who remained unrecognized as the author for many years.10

The unnamed author stated that all forms of life had evolved over time, and they had done so according to natural laws and not because of divine intervention. He included in his text a diagram of an evolutionary tree, which was the first ever to appear in print. Although Vestiges contained descriptions of the ‘progress of organic life upon the globe’, the text did not contain the word ‘evolution’. The book was enormously successful for its time, selling over 20,000 copies to readers including world leaders such as Queen Victoria and Abraham Lincoln, politicians from William Gladstone to Benjamin Disraeli, scientists like Adam Sedgwick and Thomas Henry Huxley. The book was devoured with enthusiasm by Alfred Russel Wallace. Many years later it was revealed that the author was Robert Chambers, a naturalist who espoused evolutionary theory. His belief in an explanation founded on scientific rationalism went too far when he believed in the claims of W.H. Weekes, who insisted that he had created living mites by passing electricity through a solution of potassium ferrocyanate (K4[Fe(CN)6] · 3H2O). Chambers clearly saw biological evolution as steady upward progress, though he felt it was governed by divine laws. Another prior advocate of evolution was the Reverend Baden Powell, Professor of Geometry at the University of Oxford and father of the founder of the Boy Scout movement, Robert Baden Powell. In his Essays on the Unity of Worlds, published in 1855, he wrote that all plants and animals had evolved from earlier, simpler forms, through principles that were essentially scientific. Powell also wrote to Darwin, complaining that his own views on evolution should have been cited in his book.

Charles Darwin did admit the influence of Thomas Malthus, who published several editions of An Essay on the Principle of Population between 1798 and 1826. In the opinion of Malthus, a leading British scholar, competition was an important factor regulating the growth of societies. Darwin conceded to his readers that his ideas were not original: in the introduction to The Descent of Man he emphasized: ‘The conclusion that man is the co-descendant with other species of ancient, lower, and extinct forms is not in any degree new.’ Darwin knew that; modern scholars, intent on mindless magnification of the man, have forgotten the fact. This is how science is taught to us all. Reality is somewhat different.