полная версия

полная версияNatural History of the Mammalia of India and Ceylon

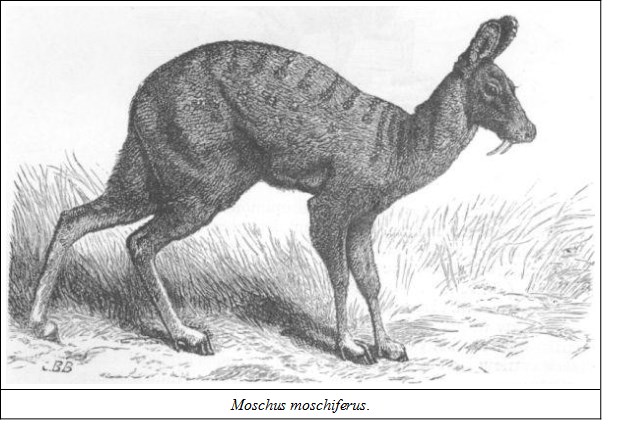

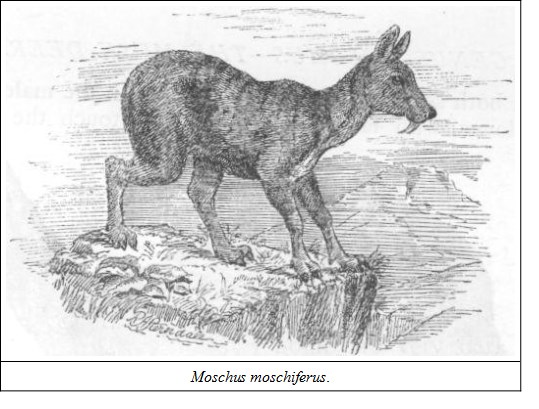

HABITAT.—Throughout the Himalayas at elevations above 8000 feet, extending also through Central and Northern Asia as far as Siberia.

DESCRIPTION.—It is difficult to describe the colour of this animal, for it so constantly changes; and, as I do not know the creature personally, I think it better to give the recorded opinions of three writers who have had personal experience. Markham describes it as a dark speckled brownish-grey, nearly black on the hind-quarters, edged down the inside with reddish-yellow; the throat, belly, and legs lighter grey. Leith Adams ('P. Z. S.' 1858, p. 528) says: "Some are very dark on the upper parts, with black splashes on the back and hips; under-parts white or a dirty white. Others are of a yellowish-white all over the upper parts, with the belly and inner sides of the thighs white. A brownish-black variety is common, with a few white spots arranged longitudinally on the back—the latter I found were young." Kinloch writes: "The prevailing colour is brownish-grey, varying in shade on the back, where it is darkest, so as to give the animal a mottled or brindled appearance."

SIZE.—Length, about 3 feet; height, 22 inches.

The musk-deer is a forest-loving animal, keeping much to one locality. It bounds with amazing agility over the steepest ground, and is wonderfully sure-footed over the most rocky hills. It ruts in winter, produces one or two young, which are driven off in about six weeks' time by the mother to shift for themselves. They begin to produce at an early age—within a year. The musk bag is an abdominal or præputial gland which secretes about an ounce of musk, worth from ten to fifteen rupees. It is most full in the rutting season; in the summer, according to Leith Adams, it hardly contains any. The musk does not seem to affect the flavour of the meat, which is considered excellent.

CERVIDÆ—THE DEEROf the horned ruminants these are the most interesting. In all parts of the world, Old and New, save the great continental island of Australia, one or other kind of stag is familiar to the people, and is the object of the chase. The oldest writings contain allusions to it, and it is frequently mentioned in the Scriptures.

"Like as the hart desireth the water brooks,"sang David. It is bound up in history and romance, and the chase of it in England is to this day a royal pastime.

However, to come back from the poetry of the thing to dry scientific details, I must premise that the two main distinctions of the Cervidæ, as separating them from the Bovidæ, are horns which are not persistent, but annually shed, and the absence of a gall bladder, which is present in nearly all the Bovidæ. The deer also, with one exception (the reindeer, Rangifer tarandus) have horns only in the males.

Regarding the shedding of these horns, it is supposed that the operation is connected with the sexual functions. It is a curious fact that castration has a powerful effect on this operation; if done early no horns appear; if later in life, the horns become persistent and are not shed.

Captain James Forsyth (in his 'Highlands of Central India'), was of opinion that the Sambar does not shed its horns annually, and states that this also is the opinion of native shikaris in Central India. This, however, requires further investigation. I certainly never heard of such a theory amongst them, nor noticed the departure from the normal state.

There have been several classifications of the Cervidæ, but I think the most complete and desirable one is that of Sir Victor Brooke (see 'P. Z. S.' 1878, p. 883), which I shall endeavour to give in a condensed form. Dr. Gray's classification was based on three forms of antlers and the shape of the tail. But Sir Victor Brooke's is founded on more reliable osteological details. As I before stated in my introductory remarks on the Ruminantia, the first and fourth digits, there being no thumb, are but rudimentary, the metacarpal bones being reduced to mere splints; the digital phalanges are always in the same place, and bear the little false hoofs, which are situated behind and a little above the large centre ones, but the metacarpal splint is not always in the same place; it may either be annexed to the phalanges, or widely separated from them and placed directly under the carpus. The position of these splints is an important factor in the classification of the Cervidæ into two divisions, distinguished by Sir Victor Brooke as the Plesiometacarpals, in which the splint is near the carpus, and the Telemetacarpals, in which the splint is far from the carpus, and articulated with the digital phalanges. All the known species of deer can be classified under these two heads; and it is a significant fact that this pedal division is borne out by certain cranial peculiarities discovered by Professor Garrod, and also, to a certain extent, by an arrangement of hair-tufts on the tarsus and metatarsus. In the Old World deer, which are with few exceptions Plesiometacarpi, those which have these tufts have them above the middle of the metatarsus, and those of the New World, which are, with one exception, Telemetacarpi, have them, when present, below the middle of the metatarsus.

There is also another character in addition to the cranial one before alluded to, which was also noticed by Professor Garrod. The first cranial peculiarity is that in Telemetacarpi, as a rule, the vertical plate developed from the lower surface of the vomer is prolonged sufficiently downwards and backwards to become anchylosed to the horizontal plate of the palatals, forming a septum completely dividing the nasal cavity into two chambers. In the Plesiometacarpi this vertical plate is not sufficiently developed to reach the horizontal plate of the palatals. The second cranial peculiarity is that in the Old World deer (Plesiometacarpi), the ascending rami of the premaxillæ articulate with the nasals with one or two exceptions, whereas in the New World deer (Telemetacarpi), with one or two exceptions, the rami of the premaxillæ do not reach the nasals. It will thus be seen that the osteological characters of the head and feet agree in a singularly fortunate manner, and, when taken in connection with the external signs afforded by the metatarsal tufts, prove conclusively the value of the system. In India we have to deal exclusively with the Plesiometacarpi, our nearest members of the other division being the Chinese water-deer (Hydropotes inermis), and probably Capreolus pygargus from Yarkand, the horns of a roebuck in velvet attached to a strip of skin having been brought down by the Mission to that country in 1873-74.

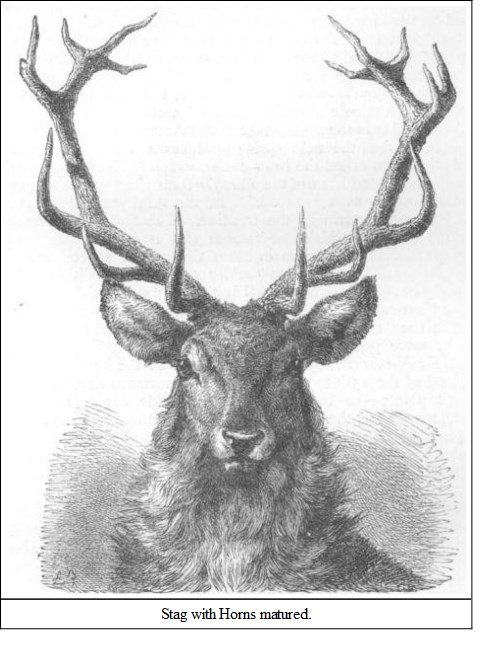

Now comes the more difficult task of subdividing these sections into genera—a subject which has taxed the powers of many naturalists, and which is still in a far from perfect state. To all proposed arrangements some exception can be taken, and the following system is not free from objection, but it is on the whole the most reliable; and this system is founded on the form of the antler, which runs from a single spike, as in the South American Coassus, to the many branches of the red deer (Cervus elaphas); and all the various changes on which we found genera are in successive stages produced in the red deer, which we may accept as the highest development; for instance, the stag in its first year develops but a single straight "beam" antler, when it is called a "brocket," and it is the same as the South American brocket (Coassus). On this being shed the next spring produces a small branch from the base of this beam, called the brow antler, which is identical almost with the single bifurcated horn of the Furcifer from Chili. The stag is then technically known as a "spayad." In the third year an extra front branch is formed, known as the tres-tine. The antler then resembles the rusine type, of which our sambar stag is an example. In the fourth year the top of the main beam throws out several small tines called "sur-royals," and the brow antler receives an addition higher up called the "bez-tine." The animal is then a "staggard." In the fifth year the "sur-royals" become more numerous, and the whole antler heavier in the "stag," whose next promotion is to that of "great hart" of ten or more points. The finest heads are found in the German forests. Sir Victor Brooke alludes to some in the hunting Schloss of Moritzburg of the 15th to 17th century, of enormous size, bearing from 25 to 50 points—50 inches round the outside curve, 10 inches in circumference round the smallest part of the beam, and of one of which the spread between the coronal tines is 74 inches. Professor Garrod mentions one as having sixty-six points, and states that Lord Powerscourt has in his possession a pair with forty-five tines. The deer with which we have to deal range from the elaphine, or red deer type, to the simple bifurcated antler of the muntjac, which consists of a beam and brow antler only. We then come to the rusine type of three points only—brow, tres, and royal tines, and of this number are also the spotted and hog deer of India, but the arrangement of the tines is different; and following the rusine type comes the rucervine, in which the tres and royal tines break out into points—the tres-tine usually bifurcate, and the royal with two, three or more points. The arrangements of the main limbs of the horns is strictly rusine—that is to say, the external and anterior tine is equal to or shorter than the royal tine, whereas it is the reverse in the axis (spotted deer), and therefore this genus should come between the two. Even in the sambar and axis there is a tendency to throw out abnormal tines. There are many examples in the Indian Museum, and I possess a magnificent head which bears a large abnormal tine on one horn, and a faint inclination in the corresponding spot on the other horn to do likewise. I have no doubt, had the animal lived another year, the second extra tine would have been developed. Professor Garrod has three phases of the rucervine type, which he calls the normal, the intermediate, and the extreme. The first has both branches of the beam, tres and royal of equal size (ex. Schomburgk's deer); the second has the tres-tine larger than the royal (ex. our swamp deer); and the extreme type is that in which the royal is represented merely by a snag, the whole horn being bent forward (ex. the Burmese Panolia Eldii). The true cervine type of horn I have already described in its progress from youth to age. The Kashmir and Sikim stags are the representatives of this form in India. In Japan there is an intermediate form in Cervus sika which has no bez-tine.

Deer have large eye-pits, but no groin-pits; feet-pits in all four, or sometimes only in the hind feet. The female has four mammæ.

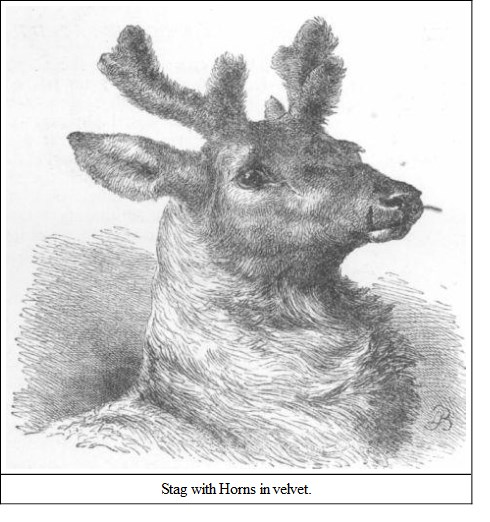

At the time of reproduction of the antlers a strong determination of blood to the head takes place, enlarging the vessels, and a fibro-cartilaginous substance is formed, which grows rapidly, and takes the form of the antler of the species. The horns in their early stage are soft and full of blood-vessels on the surface, covered with a delicate skin, with fine close-set hairs commonly called the velvet.

"As the horns ossify the periosteal veins become enlarged, grooving the external surface; the arteries are enclosed by hard osseus tubercles at the base of the horns, which coalesce and render them impervious, and, the supply of nutriment being thus cut off, the envelopes shrivel up and fall off, and the animals perfect the desquamation by rubbing their horns against trees, technically called 'burnishing.'"—Jerdon.

We now begin with the simplest form of tine we have, viz. with one basal snag only.

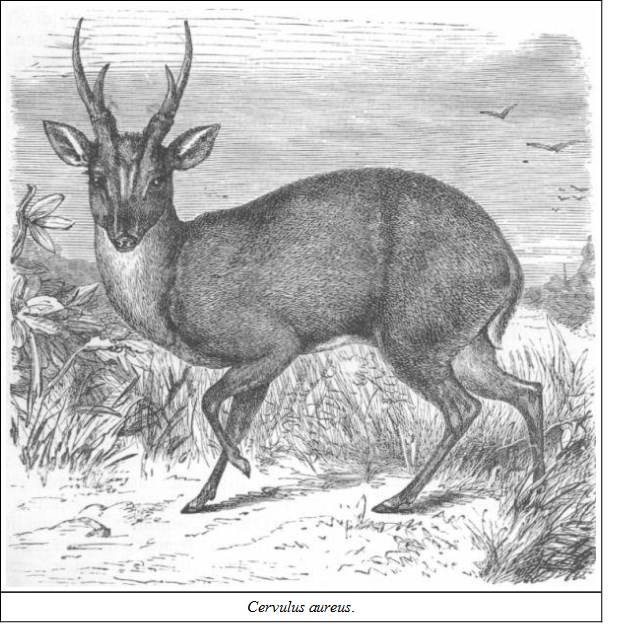

GENUS CERVULUS—THE MUNTJACS OR RIB-FACED DEEROf small size, slightly higher at the croup than at the shoulders; short tail; large pits in hind feet; no groin-pits; no tuft on the metatarsus. This genus is specially characterised, according to Sir Victor Brooke, by the absence of the lateral digital phalanges on all four feet; the proximal ends of the metacarpals are however present; horns situated on high pedicles of bone, covered with hair, continued down the face in two longitudinal ridges, between which the skin is ridged or puckered; horns small, composed of a single beam with a basal snag; skull with a very large, deep sub-orbital pit; forehead concave; large canine tusks in the upper jaw; moderate, moist muffle.

NO. 470. CERVULUS MUNTJAC vel AUREUSThe Muntjac or Rib-faced Deer (Jerdon's No. 223)NATIVE NAMES.—Kakur, Bherki, Jangli-bakra, Hindi; Maya Bengali; Ratwa, in Nepal; Karsiar, Bhotia; Siku or Suku, Lepcha; Gutra, Gutri, Gondi; Bekra or Baikur, Mahrathi; Kankuri, Canarese; Kuka-gori, Telegu; Gee, Burmese; Kidang, Javanese; Muntjac, Sundanese; Kijang, Malayan of Sumatra; Welly or Hoola-mooha, Singhalese.

HABITAT.—India, Burmah, Ceylon, the Malay peninsula, Sumatra, Java, Hainan, Banka and Borneo.

DESCRIPTION.—Between the facial ridges the creases are dark brown, with a dark line running up the inside of each frontal pedestal; all the rest of the head and upper parts a bright rufous bay; chin, throat, inside of hind-legs, and beneath tail, white; some white spots in front of the fetlocks of all four legs; fore-legs from the shoulder downwards, the legs under the tarsal joints, and a line in front of hind-legs, dark blackish-brown. The doe is a little smaller, and has little black bristly knobs where the horns of the buck are.

SIZE.—Head and body, about 3½ feet; tail, 7 inches; height, 26 to 28 inches. Jerdon gives the size of the horn 8 to 10 inches, but in this he doubtless included the pedicle, which is about 5 inches, and the horns, from 2 to 5 inches. Of the only specimen I have at present in my collection the posterior measurement from cranium to tip of horn is 6½ inches, of which the bony pedicle is 3 inches.

It is a question whether we should separate the Indian from the Malayan animal. The leading authority of the day on the Cervidæ, Sir Victor Brooke, was of opinion some time back (see 'P. Z. S.,' 1874, p. 38), that the species were identical. He says: "In a large collection of the skins, skulls, and horns of this species, which I have received from all parts of India and Burmah, and in a considerable number of living specimens which I have examined, I have observed amongst adult animals so much difference in size and intensity of coloration that I have found it impossible to retain the muntjac of Java and Sumatra as a distinct species. The muntjacs from the south of India are, as a rule, smaller than those from the north, as is also the case with the axis and Indian antelope. But even this rule is subject to many exceptions. I have received from Northern India perfectly adult, and even slightly aged, specimens of both muntjac and axis inferior in size to the average as presented by these species in Southern India. These small races are always connected with particular areas, and are doubtless the result of conditions sufficiently unfavourable to prevent the species reaching the full luxuriance of growth and beauty of which it is capable, though not sufficiently rigorous to prevent its existence." In a later article on the Cervidæ, written four years afterwards, he seems, however, to qualify his opinion in the following words: "This species appears to attain a larger size in Java, Sumatra, and Borneo than it does on the mainland; and I think it not improbable that persistent race characters may eventually be found distinguishing the muntjac of these islands from that of British India."

The rib-face is a retiring little animal, and is generally found alone, or at times in pairs. Captain Baldwin mentions four having been seen together at one time, and General McMaster mentions three; but these are rare cases.

It is very subtle in its movements, carrying its head low, and creeping, as Hodgson remarks, like a weasel under tangled thickets and fallen timber. In captivity I have found it to be a coarse feeder, and would eat meat of all kinds greedily.

Its canine teeth are very long and sharp, and have a certain amount of play in the socket, but I am unable to state whether they are ever used for any purpose, whether of utility or defence. Its call is a hoarse, sharp bark, whence it takes its name of barking deer. What Jerdon says about the length of its tongue is true; it can certainly lick a good portion of its face with it.

For excellent detailed accounts of this little deer I must refer my readers to Kinloch's 'Large Game Shooting,' and a letter by "Hawkeye," quoted by McMaster's 'Notes on Jerdon.' My space here will not allow of my quoting largely or giving personal experience, but both the above articles, as well as Captain Baldwin's notice, nearly exhaust the literature on this subject in a popular way.

The next development of antler is the rusine type, in which the main beam divides at the top into two branches, making with the basal tine a horn of three points only.

GENUS RUSA—THE RUSINE DEERAntlers with a brow tine, the beam bifurcating into a tres and royal tine; muffle large; lachrymal fossa large and deep; ante-orbital vacuity very large; rudimentary canines in both sexes, except in the hog deer; tail of moderate length; no feet-pits. The males heavily maned.

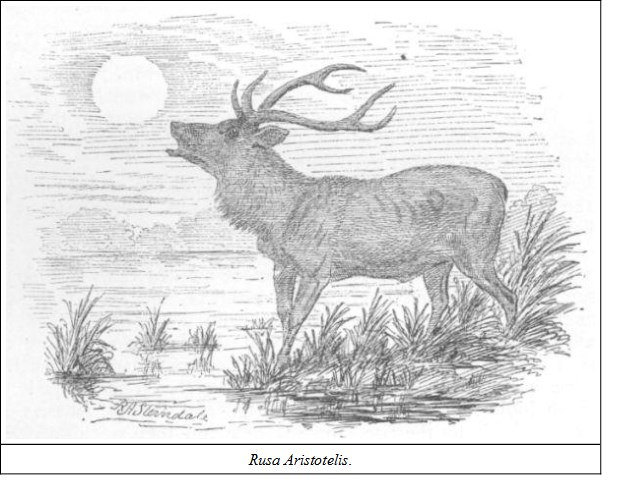

NO. 471. RUSA ARISTOTELISThe Sambar (Jerdon's No. 220)NATIVE NAMES.—Sambar or Samhar, Hindi; Jerai and Jerao in the Himalayas; Maha in the Terai; Meru, Mahrathi; Ma-oo, Gondi; Kadavi or Kadaba, Canarese; Kannadi, Telegu; Ghous or Gaoj, Eastern Bengal, the female Bholongi (Jerdon); Schap, Burmese (Blyth); Gona-rusa, Singhalese (Kellaart).

HABITAT.—Throughout India from the Himalayas to Cape Comorin; through Assam round to the east of the Bay of Bengal, down through Burmah to the Malay peninsula; it is also found in Ceylon.

DESCRIPTION.—The sambar stag is a grand animal, with fine erect carriage, heavily maned neck, and with massive horns of the rusine type. In size it is considerably larger than the red deer, and, though its horns are not so elegant, it is in its tout ensemble quite as striking an animal. In colour it is dark brown, somewhat slaty in summer; the chin, inside of limbs and tail, and a patch on the buttocks yellowish or orange yellow. The head of the sambar is very fine; the eye large and full, with immense eye-pits, which can be almost reversed or greatly dilated during excitement. The ears are large and bell-shaped, and the throat surrounded by a shaggy mane—truly a noble creature. The female and young are lighter.

SIZE.—A large stag will stand 14 hands at the withers, the length of the body being from 6 to 7 feet; tail about a foot; ears 7 to 8 inches. The average size of horns is about 3 feet, but some are occasionally found over 40 inches. Jerdon says: "some are recorded 4 feet along the curvature; the basal antler 10 to 12 inches or more." A very fine pair, with skull, in my own collection, which I value much, show the following measurements: right horn, 45 inches; left horn, 43 inches; brow antler from burr to tip, 18¼ inches circumference; just above the burr, 9 inches; circumference half-way up the beam, 7¼ inches. On the right horn underneath the tres-tine is an abnormal snag 9 inches long. The left horn has an indication of a similar branch, there being a small point, which I have no doubt would have been more fully developed had the animal lived another year.

I have had no experience of deer-shooting in the regions inhabited by the Kashmir and Sikim stags, which are approximate to our English red deer; but no sportsman need wish for a nobler quarry than a fine male sambar.

As I write visions of the past rise before me—of dewy mornings ere the sun was up; the fresh breeze at daybreak, and the waking cry of the koel and peacock, or the call of the painted partridge; then, as we move cautiously through the jungle that skirts the foot of the rocky range of hills, how the heart bounds when, stepping behind a sheltering bush, we watch the noble stag coming leisurely up the slope! How grand he looks!—with his proud carriage and shaggy, massive neck, sauntering slowly up the rise, stopping now and then to cull a berry, or to scratch his sides with his wide, sweeping antlers, looming large and almost black through the morning mists, which have deepened his dark brown hide, reminding one of Landseer's picture of 'The Challenge.' Stalking sambar is by far the most enjoyable and sportsmanlike way of killing them, but more are shot in battues, or over water when they come down to drink. According to native shikaris the sambar drinks only every third day, whereas the nylgao drinks daily; and this tallies with my own experience—in places where sambar were scarce I have found a better chance of getting one over water when the footprints were about a couple of days old. An exciting way of hunting this animal is practised by the Bunjaras, or gipsies of Central India. They fairly run it to bay with dogs, and then spear it. I have given in 'Seonee' a description of the modus operandi.

When wounded or brought to bay the sambar is no ignoble foe; even a female has an awkward way of rearing up and striking out with her fore-feet. A large hind in my collection at Seonee once seriously hurt the keeper in this manner.

Those who have read 'The Old Forest Ranger,' by Colonel Campbell, have read in it one of the finest descriptions of the stalking of this noble animal. I almost feel tempted to give it a place here; but it must give way to an extract from a less widely known, though as graphic a writer, "Hawkeye," whose letters to the South of India Observer deserve a wider circulation. I cannot find space for more than a few paragraphs, but from them the reader may judge how interesting the whole article is:—

"The hill-side we now are on rapidly falls towards the river below, where it rushes over a precipice, forming a grand waterfall, beautiful to behold. The hill-side is covered with a short, scrubby rough-leafed plant, about a foot and a-half high. Bending low, we circle round the shoulder of the slope, beyond the wood. The quick eye of the stalker catches sight of a hind's ears, at the very spot he hoped for. The stag must be nigh.

"Down on all-fours we move carefully along, the stalker keenly watching the ears. A short distance gained, and the hind detects the movement of our heads. At the same moment the upper tines of the stag's antlers are in sight; he lies to the right of the hind, about 120 yards distant, hidden by an inequality of the ground. Be still, oh beating heart! Be quiet, oh throbbing pulse! Steady, oh shaky hand, or all your toil is vain! Onward, yet only a few paces! Be not alarmed, oh cautious hind! We care not for you. Crouching still lower, we gain ground; the head and neck of our noble quarry are in sight; the hind still gazes intensely. Presently she elongates her neck in a most marvellous manner. We still gain. On once more we move, when up starts the hind. We know that in another moment she will give the warning bell, and all will vanish. The time for action has arrived. We alter our position in a second, bring the deadly weapon to bear on the stag; quickly draw a steady bead, hugging the rifle with all our might, and fire! The hinds flash across our vision like the figures in a magic lantern, and the stag lies weltering in his couch."

GENUS AXISHorns of the rusine type, but with the tres-tine longer than the royal or posterior tine; beam much bent; horns paler and smoother than in the sambar; large muffle and eye-pits; canines moderate; feet-pits in the hind-feet only; also groin-pits; tail of moderate length; skin spotted with white; said to possess a gall-bladder.