полная версия

полная версияNatural History of the Mammalia of India and Ceylon

In the Central provinces the gaur is found in several parts of the bamboo-clad spurs of the Satpura range. My experience of the animal is limited to the Seonee district, where it is restricted to the now closely preserved forests of Sonawani in the south-east bend of the range, and a few are to be seen across occasionally, near the old fort of Amodagarh, on the Hirri river.

It is also more abundant on the Pachmari and Mahadeo hills. On the east of the Bay of Bengal it is found from Chittagong through Burmah to the Malayan peninsula. It was considered that the gaur of the eastern countries was a distinct species, and is so noted in Horsfield's Catalogue, and described at some length under the name of Bibos asseel; but it appears that all this distinction was founded on the single skull of a female gaur, and is an instance of the proneness of naturalists to create new species on insufficient data. He himself remarks that when the skin was removed it was evident that the animal was nearly related to Gavæus gaurus, or, as he calls it, Bibos cavifrons. Mr. G. P. Sanderson shot a fine old male of what he supposed to be the wild gayal, and he says: "I can state that there was not one single point of difference in appearance or size between it and the bison of Southern India, except that the horns were somewhat smaller than what would have been looked for in a bull of its age in Southern India;" and this point was doubtless an individual peculiarity, for Blyth, in his 'Catalogue of the Mammals of Burmah,' says: "Nowhere does this grand species attain a finer development than in Burmah, and the horns are mostly short and thick, and very massive as compared with those of the Indian gaurs, though the distinction is not constant on either side of the Bay of Bengal."

Jerdon supposes it to have existed in Ceylon till within the present century, but I do not know on what data he founds his assertion.

DESCRIPTION.—I cannot improve on Jerdon's description, taken as it is from the writings of Hodgson, Elliot, and Fisher, so I give it as it stands, adding a few observations of my own on points not alluded to by them:—

"The skull is massive; the frontals large, deeply concave, surmounted by a large semi-cylindric crest rising above the base of the horns. There are thirteen pairs of ribs.40 The head is square, proportionately smaller than in the ox; the bony frontal ridge is five inches above the frontal plane; the muzzle is large and full, the eyes small, with a full pupil (? iris) of a pale blue colour. The whole of the head in front of the eyes is covered with a coat of close short hair, of a light greyish-brown colour, which below the eyes is darker, approaching almost to black; the muzzle is greyish and the hair is thick and short; the ears are broad and fan-shaped; the neck is sunk between the head and back, is short, thick, and heavy. Behind the neck and immediately above the shoulder rises a gibbosity or hump of the same height as the dorsal ridge. This ridge rises gradually as it goes back, and terminates suddenly about the middle of the back; the chest is broad; the shoulder deep and muscular; the fore-legs short, with the joints very short and strong, and the arm exceedingly large and muscular; the hair on the neck and breast and beneath is longer than on the body, and the skin of the throat is somewhat loose, giving the appearance of a slight dewlap; the fore-legs have a rufous tint behind and laterally above the white. The hind-quarters are lighter and lower than the fore, falling suddenly from the termination of the dorsal ridge; the skin of the neck, shoulders, and thigh is very thick, being about two inches and more.

"The cow differs from the bull in having a slighter and more graceful head, a slender neck, no hump; and the points of the horns do not turn towards each other at the tip, but bend slightly backwards, and they are much smaller; the legs too are of a purer white. The very young bull has the forehead narrower than the cow, and the bony frontal ridge scarcely perceptible. The horns too turn more upwards. In old individuals the hair on the upper parts is often worn off. The skin of the under parts when uncovered is deep ochrey-yellow."—'Mammals of India,' p. 302.

The fineness of the leg below the knee is another noticeable feature, and also the well-formed pointed hoof, which leaves an imprint like that of a large deer. Mr. Sanderson states in his book that the bison, after a sharp hunt, gives out an oily sweat, and in this peculiarity he says it differs from domestic cattle, which never sweat under any exertion. This I have not noticed.

The period of gestation seems to be about the same as that of the domestic cow, and the greatest number of calves are born in the summer.

SIZE.—I cannot speak personally, for I regret now that I took no measurements in the days when I was acquainted with these magnificent animals, but the experiences of others I give as follows:—

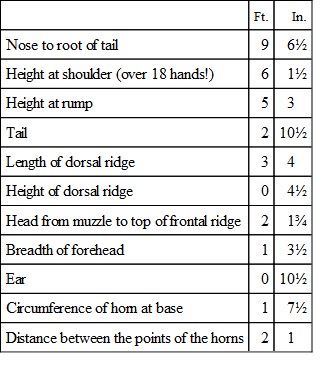

Sir Walter Elliot gives—

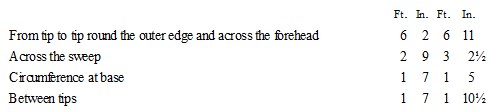

I give the measurements of two fine heads:—

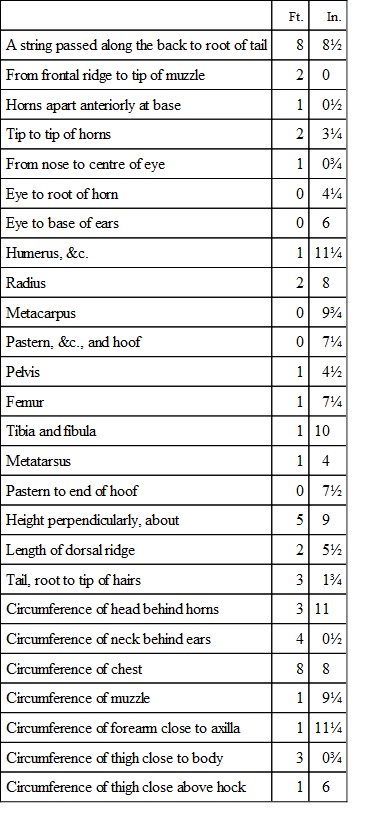

The following careful measurements are recorded by Mr. Blyth ('J. A. S. B.,' vol. xi., 1842, p. 588), and were furnished to him by Lieut. Tickell from the recently-killed animal, in order to assist in the setting up of the specimen in the Asiatic Museum:—

I feel tempted to let my pen run away with me into descriptions of the exciting scenes of the past in the chase of this splendid creature—the noblest quarry that the sportsman can have, and the one that calls forth all his cunning and endurance. As I lately remarked in another publication, I know of no other animal of which the quest calls forth the combined characteristics of the ibex, the stag and the tiger-hunter. Some of my own experiences I have described in 'Seonee;' but let those who wish to learn the poetry of the thing read the glowing, yet not less true pages of Colonel Walter Campbell's 'Old Forest Ranger;' and for clear practical information, combined also with graphic description, the works of Captain J. Forsyth and Mr. G. P. Sanderson ('The Highlands of Central India' and 'Thirteen years among the Wild Beasts').

The gaur prefers hilly ground, though it is sometimes found on low levels. It is extremely shy and retiring in its habits, and so quick of hearing that extreme care has to be taken in stalking to avoid treading on a dry leaf or stick. I know to my cost that the labour of hours may be thrown away by a moment of impatience. In spite of all the wondrous tales of its ferocity, it is as a rule a timid, inoffensive animal. Solitary bulls are sometimes dangerous if suddenly come upon. I once did so, and the bull turned and dashed up-hill before I could get a shot, whereas a friend of mine, to whom a similar thing occurred a few weeks before, was suddenly charged, and his gun-bearer was knocked over. The gaur seldom leaves its jungles, but I have known it do so on the borders of the Sonawani forest, in order to visit a small tank at Untra near Ashta, and the cultivation in the vicinity suffered accordingly.

Hitherto most attempts to rear this animal when young have failed. It is said not to live over the third year. Though I offered rewards for calves for my collection, I never succeeded in getting one. I have successfully reared most of the wild animals of the Central provinces, but had not a chance of trying the bison.

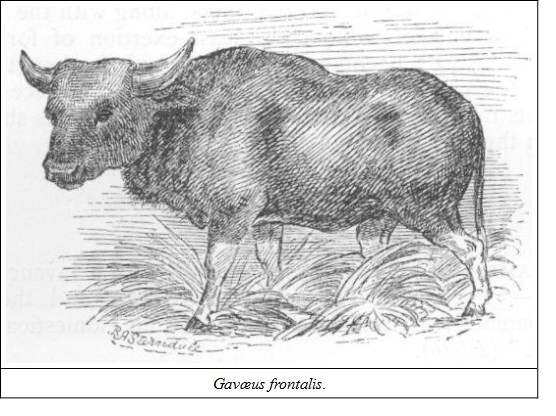

NO. 465. GAVÆUS FRONTALISThe Mithun or GayalNATIVE NAMES.—Gayal, Gavi or Gabi, Gabi-bichal (male), Gabi-gai (female); Bunerea-goru in Chittagong and Assam; Mithun.

HABITAT.—The hilly tracts east of the Brahmaputra, at the head of the Assam valley, the Mishmi hills, in hill Tipperah, Chittagong, and then southwards through Burmah to the hills bordering on the Koladyne river.

DESCRIPTION.—Very like the gaur at first sight, but more clumsy looking; similarly coloured, but with a small dewlap; the legs are white as in the last species. In the skull the forehead is not concave as in the gaur, but flat, and if anything rather convex. The back has a dorsal ridge similar to that of the gaur.

The gayal is of a much milder disposition than the gaur, and is extensively domesticated, and on the frontiers of Assam is considered a valuable property by the people. The milk is rich and the flesh good. There are purely domesticated mithuns bred in captivity, but according to many writers the herds are recruited from the wild animals, which are tempted either to interbreed, or are captured and tamed. In Dr. F. Buchanan Hamilton's MS. (see Horsfield's 'Cat. Mammalia, E. I. C. Mus.') the following account is given: "These people (i.e. the inhabitants of the frontiers) have tame gayals, which occasionally breed, but the greater part of their stock is bred in the woods and caught; after which, being a mild animal, it is easily domesticated. The usual manner employed to catch the full-grown gayal is to surround a field of corn with a strong fence. One narrow entrance is left, in which is placed a rope with a running noose, which secures the gayal by the neck as he enters to eat the corn; of ten so caught perhaps three are hanged by the noose running too tight, and by the violence of their struggling. Young gayals are caught by leaving in the fence holes of a size sufficient to admit a calf, but which excludes the full-grown gayal; the calves enter by these holes, which are then shut by natives who are watching, and who secure the calves. The gayal usually goes in herds of from twenty to forty, and frequents dry valleys and the sides of hills covered with forest." Professor Garrod, in his Ungulata in Cassell's Natural History, quotes the following account from Mr. Macrae concerning the way in which the Kookies of the Chittagong hill regions catch the wild gayal: "On discovering a herd of wild gayals in the jungle they prepare a number of balls, the size of a man's head, composed of a particular kind of earth, salt and cotton. They then drive their tame gayals towards the wild ones, when the two herds soon meet and assimilate into one, the males of the one attaching themselves to the females of the other, and vice versâ. The Kookies now scatter their balls over such parts of the jungles as they think the herd most likely to pass, and watch its motions. The gayals, on meeting these balls as they pass along, are attracted by their appearance and smell, and begin to lick them with their tongues, and, relishing the taste of the salt and the particular earth composing them, they never quit the place till all the balls are consumed. The Kookies, having observed the gayals to have once tasted their balls, prepare a sufficient supply of them to answer the intended purpose, and as the gayals lick them up they throw down more; and it is to prevent their being so readily destroyed that the cotton is mixed with the earth and the salt. This process generally goes on for three changes of the moon or for a month and a-half, during which time the tame and the wild gayals are always together, licking the decoy balls, and the Kookie, after the first day or two of their being so, makes his appearance at such a distance as not to alarm the wild ones. By degrees he approaches nearer and nearer, until at length the sight of him has become so familiar that he can advance to stroke his tame gayals on the back and neck without frightening the wild ones. He next extends his hand to them and caresses them also, at the same time giving them plenty of his decoy balls to lick. Thus, in the short space of time mentioned, he is able to drive them, along with the tame ones, to his parrah or village, without the least exertion of force; and so attached do the gayals become to the parrah, that when the Kookies migrate from one place to another, they always find it necessary to set fire to the huts they are about to abandon, lest the gayals should return to them from the new grounds."

NO. 466. GAVÆUS SONDAICUSThe Burmese Wild OxNATIVE NAME.—Tsoing, Burmese; Banteng of the Javanese.

HABITAT.—"Pegu, the Tenasserim provinces, and the Malayan peninsula, Sumatra, Borneo and Java; being domesticated in the island of Bali" (Blyth).

DESCRIPTION.—This animal resembles the gaur in many respects, and it is destitute of a dewlap, but the young and the females are bright chestnut. The bulls become black with age, excepting always the white stockings and a white patch on each buttock.

SIZE.—About the same as the last two species.

This animal has bred in captivity, and has also interbred with domestic cattle. Blyth says he saw in the Zoological Gardens of Amsterdam a bull, cow, and calf in fine condition. "The bull more especially has an indication of a hump, which, however, must be specially looked for to be noticed, and he has a broad and massive neck like the gaur, but no raised spinal ridge, nor has either of these species a deep dewlap like the gayal" ('Cat. Mamm. Burmah'). The banteng cow is much slighter in build, and has small horns that incline backwards, and she retains her bright chestnut colour permanently.

GENUS POEPHAGUS—THE YAKSomewhat smaller than the common ox, with large head; nose hairy, with a moderate sized bald muffle between nostrils; broad neck without dewlap; cylindrical horns; no hump or dorsal ridge, and long hair on certain parts of the body. Requires an intensely cold climate.

NO. 467. POEPHAGUS GRUNNIENSThe Yak or Grunting OxNATIVE NAMES.—Yak, Bubul, Soora-goy, Dong, in Thibet; Bun-chowr, Hindi; Brong-dong, Thibetan.

HABITAT.—The high regions of Thibet and Ladakh, the valley of the Chang Chenmo, and the slopes of the Kara Koram mountains (Kinloch).

DESCRIPTION.—"In size it is somewhat less than the common or domestic ox. The head is large, and the neck proportionally broad, without any mane or dewlap, having a downward tendency; the horns are far apart, placed in front of the occipital ridge, cylindrical at the base, from which they rise obliquely outward and forward two-thirds of their length, when they bend inward with a semi-circular curve, the points being directed to each other from the opposite sides; the muffle is small; the border of the nostrils callous; the ears short and hairy. At the withers there is a slight elevation, but no protuberance or hump, as in the Indian ox. The dorsal ridge not prominent; body of full dimensions; rump and hinder parts proportionally large; limbs rather small and slender; hoofs smooth, square, and well defined, not expanded as in the musk-ox; anterior false hoofs small, posterior large; tail short, not reaching beyond the houghs, naked for some inches at the root, very bushy, lax, and expanded in the middle; colour black throughout, but varying in tint according to the character of the hairy covering; this, on the anterior parts, the neck, shoulders, back, and sides, is short, soft, and of a jet-black colour, but long, shaggy, pendulous, and shining on the sides of the anterior extremities, and from the medial part of the abdomen over the thighs to the hinder parts" (Horsfield, 'Cat. Mam. Ind. Mus.').

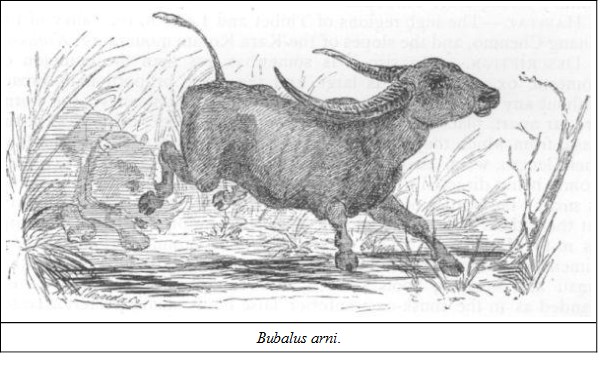

GENUS BUBALUS—THE BUFFALOSHorns very large, depressed and sub-trigonal at the base, attached to the highest line of the frontals, inclining upwards and backwards, conical towards the tip and bending upwards; muffle large, square. No hump or dorsal ridge; thirteen pairs of ribs; hoofs large.

NO. 468. BUBALUS ARNIThe Wild Buffalo (Jerdon's No. 239)NATIVE NAMES.—Arna (male), Arni (female), Arna-bhàinsa, Jangli-bhains, Hindi; Mung, Bhagulpore; Gera-erumi, Gondi; Karbo of the Malays; Moonding of the Sundanese.

HABITAT.—In the swampy terai at the foot of the hills from Oude to Bhotan, in the plains of Lower Bengal as far west as Tirhoot, in Assam and in Burmah, in Central India from Midnapore to Rajpore, and thence nearly to the Godavery; also in Ceylon.

DESCRIPTION.—This animal so closely resembles the common domesticated buffalo that it seems hardly necessary to attempt a description. The wild one may be a trifle larger, but every one in India is familiar with the huge, ungainly, stupid-looking creature, with its bulky frame, black and almost hairless body, back-sweeping horns, and long narrow head.

SIZE.—A large male will stand 19 hands at the shoulder and measure 10¼ feet from nose to root of tail, which is short, reaching only to the hocks. Horns vary greatly, but the following are measurements of large pairs: In the British Museum are a pair without the skull. These horns measure 6 feet 6 inches each, which would give, when on the head, an outer curve measurement of nearly 14 feet. Another pair in the British Museum measure on the skull 12 feet 2 inches from tip to tip and across the forehead, but these horns do not exactly correspond in length and shape.

The buffalo never ascends mountains like the bison, but keeps to low and swampy ground and open grass plains, living in large herds, which occasionally split up into smaller ones during the breeding season in autumn. The female produces one, or sometimes two in the summer, after a period of gestation of ten months.

Forsyth doubts their interbreeding with the domestic race, but I see no reason for this. The two are identically the same, and numerous instances have been known of the latter joining herds of their wild brethren; and I have known cases of the domestic animal absconding from a herd and running wild. Such a one was shot by a friend of mine in a jungle many miles from the haunts of men, but yet quite out of the range of the wild animal. Probably it had been driven from a herd. Domestic buffalo bulls are much used in the Central provinces for carrying purposes. I had them yearly whilst in camp, and noticed that one old bull lorded it over the others, who stood in great awe of him; at last one day there was a great uproar; three younger animals combined, and gave him such a thrashing that he never held up his head again. In a feral state he would doubtless have left the herd and become a solitary wanderer. Dr. Jerdon, in his 'Mammals of India,' says: "Mr. Blyth states it as his opinion that, except in the valley of the Ganges and Burrampooter, it has been introduced and become feral. With this view I cannot agree, and had Mr. Blyth seen the huge buffalos I saw on the Indrawutty river (in 1857), he would, I think, have changed his opinion. They have hitherto not been recorded, south of Raepore, but where I saw them is nearly 200 miles south. I doubt if they cross the Godavery river.

"I have seen them repeatedly, and killed several in the Purneah district. Here they frequent the immense tracts of long grass abounding in dense, swampy thickets, bristling with canes and wild roses; and in these spots, or in the long elephant-grass on the bank of jheels, the buffalos lie during the heat of the day. They feed chiefly at night or early in the morning, often making sad havoc in the fields, and retire in general before the sun is high. They are by no means shy (unless they have been much hunted), and even on an elephant, without which they could not be successfully hunted, may often be approached within good shooting distance. A wounded one will occasionally charge the elephant, and, as I have heard from many sportsmen, will sometimes overthrow the elephant. I have been charged by a small herd, but a shot or two as they are advancing will usually scatter them."

The buffalo is, I should say, a courageous animal—at least it shows itself so in the domesticated state. A number of them together will not hesitate to charge a tiger, for which purpose they are often used to drive a wounded tiger out of cover. A herdsman was once seized by a man-eater one afternoon a few hundred yards from my tent. His cows fled, but his buffalos, hearing his cries, rushed up and saved him.

The attachment evinced by these uncouth creatures to their keepers was once strongly brought to my notice in the Mutiny. In beating up the broken forces of a rebel Thakoor, whom we had defeated the previous day, I, with a few troopers, ran some of them to bay in a rocky ravine. Amongst them was a Brahmin who had a buffalo cow. This creature followed her master, who was with us as a prisoner, for the whole day, keeping at a distance from the troops, but within call of her owner's voice. When we made a short halt in the afternoon, the man offered to give us some milk; she came to his call at once, and we had a grateful draught, the more welcome as we had had nothing to eat since the previous night. That buffalo saved her master's life, for when in the evening the prisoners were brought up to court martial and sentenced to be hanged, extenuating circumstances were urged for our friend with the buffalo, and he was allowed to go, as I could testify he had not been found with arms in his hands; and I had the greatest pleasure in telling him to be off, and have nothing more to do with rebel Thakoors. Jerdon says the milk of the buffalo is richer than that of the cow. I doubt this. I know that in rearing wild animals buffalos' milk is better than cows' milk, which is far too rich, and requires plentiful dilution with water.

There is a very curious little animal allied to the buffalo, of which we have, or have had, a specimen in the Zoological Gardens at Alipore—the Anoa depressicornis; it comes from the Island of Celebes, and seems to link the buffalo with the deer. It is black, with short wavy hair.

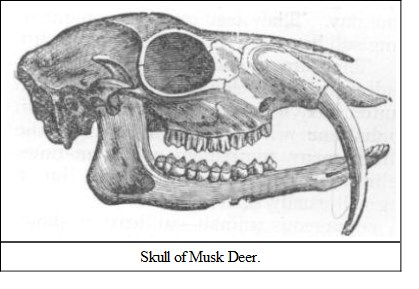

Before passing on to the true Cervidæ I must here place an animal commonly called a deer, and generally classed as such—the musk-deer according to some naturalists. There is no reason, save an insufficient one, that this creature should be so called and classed, there being much evidence in favour of its alliance to the antelopes. In the first place it has a gall bladder, which the Cervidæ have not, with the exception, according to Dr. Crisp, of the axis ('P. Z. S.'). On the other hand it has large canine tusks like the muntjacs, deerlets, and water-deer, and, as these are all aberrant forms of the true Cervidæ, there is no reason why the same character should not be developed in the antelopes. Its hair is more of the goat than the deer, and the total absence of horns removes a decided proof in favour of one or the other. The feet are more like some of the Bovidæ than the generality of deer, with the exception, perhaps, of Rangifer (the reindeer), the toes being very much cloven and capable of grasping the rocky ground on which it is found. A very eminent authority, however, Professor Flower, is in favour of placing the musk-deer with the Cervidæ, and he instances the absence of horns as in favour of this opinion, for in none of the Bovidæ are the males hornless. There are many other points also, such as the fawns being spotted, some intestinal peculiarities, and the molar and premolar teeth being strictly cervine, which strengthen him in his opinion. (See article on the structure and affinities of the musk-deer, 'P. Z. S.' 1879, p. 159.)

GENUS MOSCHUS—THE MUSK DEERCanines in both sexes, very long and slender in the male; no horns; feet much cloven, with large false hoofs that touch the ground; the medium metacarpals fused into a solid cannon bone; in the skull the intermaxillaries join the nasals; hinder part of tarsus hairy; fur thick, elastic, and brittle; muffle large; no eye, feet, or groin-pits; a large gland or præputial bag under the stomach in the males, which contains the secretion known in commerce as "musk."

NO. 469. MOSCHUS MOSCHIFERUSThe Musk DeerNATIVE NAMES.—Kastura, Hindi; Rous, Roos, and Kasturé, in Kashmir; La-lawa, Thibetan; Rib-jo, Ladakhi; Bena in Kunawur (Jerdon); Mussuck-naba', Pahari (Kinloch).