полная версия

полная версияNatural History of the Mammalia of India and Ceylon

ORDER EDENTATA

These are animals without teeth, according to the name of their order. They are however without teeth only in the front of the jaw in all, but with a few molars in some, the Indian forms however are truly edentate, having no teeth at all. In those genera where teeth are present there are molars without enamel or distinct roots, but with a hollow base growing from below and composed of three structures, vaso-dentine, hard dentine and cement, which, wearing away irregularly according to hardness, form the necessary inequality for grinding purposes.

The order is subdivided into two groups: Tardigrada, or sloths, and Effodientia or burrowers. With the former we have nothing to do, as they are peculiar to the American continent. The burrowers are divided into the following genera: Manis, the scaly ant-eaters; Dasypus, the armadillos; Chlamydophorus, the pichiciagos; Orycteropus, the ant-bears, and Myrmecophaga, the American ant-eaters.

Of these we have only one genus in India; Manis, the pangolin or scaly ant-eater, species of which are found in Africa as well as Asia.

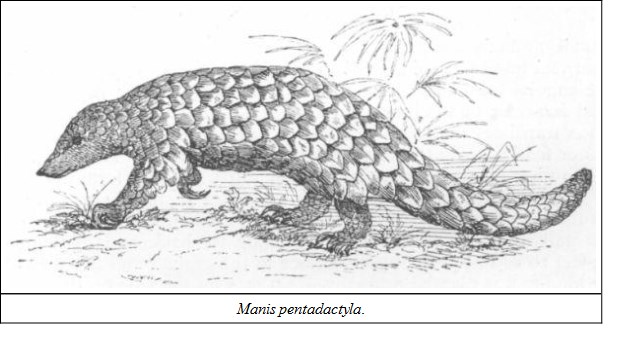

GENUS MANISSmall animals from two to nearly five feet in length; elongated cylindrical bodies with long tails, covered from snout to tip of tail with large angular fish-like scales, from which in some parts of India they are called bun-rohu, or the jungle carp; also in Rungpore Keyot-mach, which Jerdon translates the fish of the Keyots, but which probably means khet-mach or field-fish—but in this I am open to correction. The scales overlap like tiles, the free part pointing backwards. These form its defensive armour, for, although the manis possesses powerful claws, it never uses them for offence, but when attacked rolls itself into a ball.

In walking it progresses slowly, arching its back and doubling its fore-feet so as to put the upper surface to the ground and not the palm. The hind-foot is planted normally—that is, with the sole on the earth.

The tongue is very long and worm-like, and covered with glutinous saliva; and, much of this moisture being required, the sub-maxillary glands are very large, reaching down under the skin of the neck on to the chest.

The external ear is very small, and internally it is somewhat complicated, there being a large space in the temporal bone which communicates with the internal ear, so that, according to Professor Martin-Duncan, one tympanum is in communication with the other.

These animals are essentially diggers. The construction of their fore-arms is such as to economise strength and the effectiveness of their excavating instruments. The very doubling up of their toes saves the points of their claws. The joints of the fore-fingers bend downwards, and are endowed with powerful ligaments; and in the wrist the scaphoid and semi-lunar bones are united by bone, which increases its strength. As Professor Martin-Duncan remarks: "Every structure in the creature's fore-limbs tends to the promotion of easy and powerful digging, and, as the motion of scratching the ground is directly downwards and backwards, the power of moving the wrist half-round and presenting the palm more or less upwards, as in the sloths and in man, does not exist. In order to prevent this pronation and supination the part of the fore-arm bone, the radius, next to the elbow, is not rounded, but forms part of a hinge joint." He also notices another interesting peculiarity in the chest of this animal, the breast-bone being very long; the cartilage at end large, with two long projections resembling those of the lizards. There is no collar-bone.

NO. 480. MANIS PENTADACTYLA vel BRACHYURAThe Five-fingered or Short-tailed Pangolin (Jerdon's No. 241)NATIVE NAMES.—Bajar-kit, Bajra-kapta, Sillu, Sukun-khor, Sal-salu, Hindi; Shalma of the Bauris; Armoi of the Kols; Kauli-mah, Kauli-manjra, Kassoli-manjur, Mahratti; Alawa, Telegu; Alangu, Malabarese; Bun-rohu in the Deccan, Central provinces, &c.; Keyot-mach, in Rungpore; Katpohu, in parts of Bengal; Caballaya, Singhalese.

HABITAT.—Throughout India. Jerdon says most common in hilly districts, but nowhere abundant. I have found it myself in the Satpura range, where it is called Bun-rohu.

DESCRIPTION.—Tail shorter than the body, broad at the base, tapering gradually to a point. Eleven to thirteen longitudinal rows of sixteen scales on the trunk, and a mesial line of fourteen on the tail; middle nail of fore-foot much larger than the others. Scales thick, striated at base; yellowish-brown or light olive. Lower side of head, body, and feet, nude; nose fleshy; soles of hind-feet dark.

SIZE.—Head and body, 24 to 27 inches; tail, about 18. Jerdon gives the weight of a female measuring 40 inches as 21 pounds.

This species burrows in the ground to a depth of a dozen feet, more or less, where it makes a large chamber, sometimes six feet in circumference. It lives in pairs, and has from one to two young ones at a time in the spring months. Sir W. Elliot, who gives an interesting detailed account of it, says that it closes up the entrance to its burrow with earth when in it, so that it would be difficult to find it but for the peculiar track it leaves (see 'Madras Journal,' x. p. 218). There is also a good account of it by Tickell in the 'Journal As. Soc. of Bengal,' xi. p. 221, and some interesting details regarding one in captivity by the late Brigadier-General A. C. McMaster in his 'Notes on Jerdon.' I have had specimens brought to me by the Gonds, but found them very somnolent during the day, being, as most of the above authors state, nocturnal in its habits. The first one I got had been kept for some time without water, and drank most eagerly when it arrived, in the manner described by Sir Walter Elliot, "by rapidly darting out its long extensile tongue, which it repeated so quickly as to fill the water with froth."

The only noise it makes is a faint hiss. It sleeps rolled up, with the head between the fore-legs and the tail folded firmly over all.

The natives believe in the aphrodisine virtues of its flesh.

NO. 481. MANIS AURITAThe Eared Pangolin (Jerdon's No. 242)HABITAT.—Sikhim, and along the hill ranges of the Indo-Chinese frontier. Dr. Anderson says it is common in all the hilly country east of Bhamo.

DESCRIPTION.—Tail shorter and not so thick at the base as that of the last; the body less heavy; smaller and darker scales; muzzle acute; ears conspicuous; scales of head and neck not so small in proportion as in M. pentadactyla.

SIZE.—Head and body of one mentioned by Jerdon, 19 inches; tail, 15¼ inches.

NO. 482. MANIS JAVANICAThe Javan Ant-eaterHABITAT.—Burmah and the Malayan peninsula; also Tipperah.

DESCRIPTION.—To be distinguished from the two preceding species by the greater number of longitudinal rows of scales, M. pentadactyla having from eleven to thirteen, M. aurita from fifteen to eighteen, and M. Javanica nineteen. Taking the number of scales in the longitudinal mesial line from the nose to the tip of the tail in M. pentadactyla, it is forty-two; in aurita forty-eight to fifty-six; in Javanica as high as sixty-four; on the tail the scales are: M. pentadactyla, fourteen; M. aurita sixteen to twenty; M. Javanica thirty.

I am indebted to Dr. Anderson's 'Zoological and Anatomical Researches' for the following summary of characteristics:—

"M. pentadactyla by its less heavy body; by its tail, which is broad at the base, tapering gradually to a point, and equalling the length of the head and trunk; by its large light olive-brown scales, of which there are only from eleven to thirteen longitudinal rows on the trunk, and a mesial line of fourteen on the tail; and by its powerful fore-claws, the centre one of which is somewhat more than twice as long as the corresponding claw of the hinder extremity. M. aurita is distinguished from M. pentadactyla by its less heavy body; by its rather shorter tail, which has less basal breadth than M. pentadactyla; by its smaller and darker brown, almost black scales in the adult, which are more numerous, there being from fifteen to eighteen longitudinal rows on the trunk, seventeen rows being the normal number, and sixteen to twenty caudal plates in the mesial line; and by its strong fore-claws, the middle one of which is not quite twice as long as the corresponding claw on the hind foot.

"M. Javanica is recognised by its body being longer and more attenuated than in the two foregoing species; by its narrower and more tapered tail; by its longer and more foliaceous or darker olive-brown scales, of which there are nineteen longitudinal rows on the trunk, and as many as thirty along the mesial line of the tail; and by the claws of the fore-feet being not nearly so long as in M. aurita, and being but little in excess of the claws of the hind-feet."

APPENDIX A

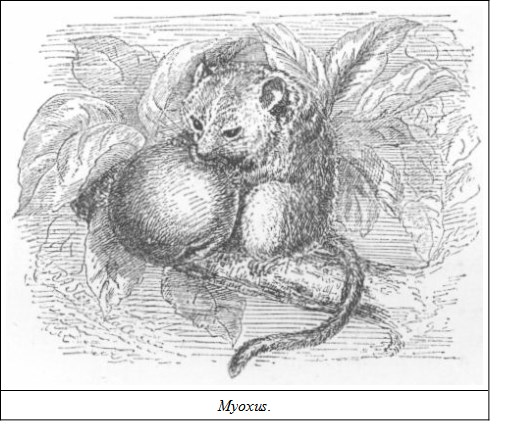

FAMILY MYOXIDÆ—THE DORMICEThese small rodents approximate more to the squirrels than the true mice; but they differ from all others intestinally by the absence of a cæcum. They have four rooted molars in each upper and lower jaw, the first of each set being smaller than the other three, the crowns being composed of transverse ridges of enamel. In form they are somewhat squirrel-like, with short fore-limbs, and hairy, though not bushy, tails. The thumb is rudimentary, with a small, flat nail; hind-feet with five toes.

The common English dormouse is a most charming little animal, and a great pet with children. I have had several, and possess a pair now which are very tame. They are elegant little creatures, about three inches long, with tails two and a-half inches; soft deep fur of a pale reddish-tawny above, pale yellowish-fawn below, and white on the chest. The eyes are large, lustrous, and jet-black. The tails of some are slightly tufted at the end. They are quite free from the objectionable smell of mice. In their habits they are nocturnal, sleeping all day and becoming very lively at night. I feed mine on nuts, and give them a slice of apple every evening; no water to drink, unless succulent fruits are not to be had, and then sparingly. The dormouse in its wild state lives on fruits, seeds, nuts and buds. In cold countries it hibernates, previous to which it becomes very fat. It makes for itself a little globular nest of twigs, grass, and moss, pine-needles, and leaves, in which it passes the winter in a torpid state. "The dormouse lives in small societies in thickets and hedgerows, where it is as active in its way amongst the bushes and undergrowth as its cousin the squirrel upon the larger trees. Among the small twigs and branches of the shrubs and small trees the dormice climb with wonderful adroitness, often, indeed, hanging by their hind feet from a twig, in order to reach and operate on a fruit or a nut which is otherwise inaccessible, and running along the lower surface of a branch with the activity and certainty of a monkey" (Dallas). This little animal is supposed to breed twice in the year—in spring and autumn. It is doubtful whether we have any true Myoxidæ in India, unless Mus gliroides should turn out to be a Myoxus. The following is mentioned in Blanford's 'Eastern Persia': Myoxus pictus—new species, I think; I regret I have not the book by me at present—also Myoxus dryas, of which I find a pencil note in my papers. Mouse-red on the back, white belly with a rufous band between; white forehead; a black stripe from the nose to the ears, passing through the eye.

APPENDIX B

The above illustration was by accident omitted from the text.

APPENDIX C

NOTES ON SOME OF THE FOREGOING SPECIES

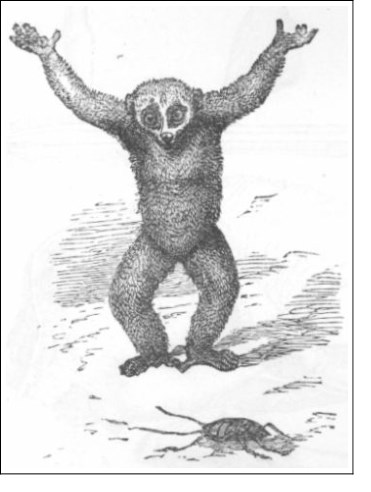

The Slow Loris, No. 28 .—This creature sometimes assumes the erect posture, though in general it creeps. The following illustration shows an attitude observed and sketched by Captain Tickell, as the animal was about to seize a cockroach. When it had approached within ten or twelve inches, it drew its hind feet gradually forward until almost under its chest; it then cautiously and slowly raised itself up into a standing position, balancing itself awkwardly with its uplifted arms; and then, to his astonishment, flung itself, not upon the insect, which was off "like an arrow from a Tartar's bow," but on the spot which it had, half a second before, tenanted.

Trade Statistics of Fur-skins, Mustelidæ .—The Philadelphia Times, in an article on furs, says that the best sealskins come from the antarctic waters, principally from the Shetland Islands. New York receives the bulk of American skins, which are shipped to various ports. London is the great centre of the fur trade of the world. In the United States the sea-bear of the north has the most valuable skin. Since 1862 over 500,000 have been killed on Behring Island alone. In 1867 there were 27,500 sea-bears killed; in 1871 there was a very large decrease, only 3,614 being killed. There were 26,960 killed in 1876; and in 1880 the number killed was 48,504, a large increase. Sea-otter fur is about as expensive as any, and some 48,000 skins are used yearly. Over 100,000 marten or Russian sable skins are annually used. Only about 2,000 silver foxes are caught every year; and about 6,500 blue foxes. Other fox skins are used more or less. About 600 tiger skins are used yearly, over 11,000 wild cat skins, and a very large trade is being carried on in house cat skins. About 350,000 skunk and 42,000 monkey skins are utilised annually. The trade in ermine skins is falling off, as is also the trade in chinchilla. About 3,000,000 South American nutrias are killed every year, and a very large business is carried on in musk-rat skins. About 15,000 each of American bear and buffalo skins were used last year. There are also used each year about 3,000,000 lamb, 5,000,000 rabbit, 6,000,000 squirrel, and 620,000 filch skins; also 195,000 European hamster, and nearly 5,000,000 European and Asiatic hares.

Tigers, No.201 .—Since writing on the subject of the size of tigers I have received the following extract from a letter addressed to the editor of The Asian. Both the animals were measured on the ground before being skinned, and in the presence of all whose names are given:—

"Tiger shot on the 6th of July, 1882. Party present: C. A. Shillingford, Esq.; J. L. Shillingford, Esq.; F. A. Shillingford, Esq.; A. J. Shillingford, Esq. Length of head, 1 ft. 8½ in.; body, 5 ft. 6½ in.; tail, 3 ft. 6½ in.; total length, 10 ft. 9½ in. Height at shoulder, 3 ft. 7 in.

"Tiger shot on the 17th of March, 1883. Party present: The Earl of Yarborough; A. E. Fellowes, Esq.; Col. R. C. Money, B.S.C.; Capt. C. H. Mayne, A.D.C.; Lieut. R. Money; J. D. Shillingford, Esq. Length of head, 1 ft. 8 in.; body, 5 ft. 7 in.; tail, 3 ft. 5½ in.; total length, 10 ft. 8½ in. Height at shoulder, 3 ft. 8½ in.; girth of head round jaw, 3 ft. 1½ in.; girth of body round chest, 4 ft. 7 in.

"The latter animal, though not so long as the former, was the larger animal of the two, being more massively built, and by far the finer specimen of a tiger. He was shot by Mr. Fellowes while out shooting in the Maharajah of Darbhanga's hunt in the Morung Terai."

The following is an extract from a letter lately received by me from General Sir Charles Reid, K.C.B., with reference to an enormous tiger killed by him:—

"I had a tiger in the Exhibition of 1862, and which is now in the museum at Leeds, which was the largest tiger I ever killed or ever saw. As he lay on the ground he measured 12 feet 2 inches—his height I did not measure—from the tip of one ear to the tip of the other 19½ inches. I never took skull measurements, nor did I ever weigh a tiger. I had another in the International Exhibition, which measured 11½ feet fair measurement as he lay on the ground. The one at Leeds 12 feet 2 inches, as before mentioned, is not now more than 11 feet 6 inches. Mr. Ward was not satisfied with the Indian curing, and had it done over again, and it shrunk nearly a foot. The three tigers41 mentioned are the largest I ever killed—all Dhoon tigers."

Elephants, No. 425 .—The two Indian elephants now in the Zoological Society's Gardens, in Regent's Park, are interesting examples of the growth of these animals in captivity. I regret extremely that I have not been able to get accurate statistics regarding them before leaving England; I was obliged to put off several proposed visits to the Gardens in consequence of ill health, and am now correcting the final proof-sheets of this work on board ship, preparatory to posting them at Suez, so I must trust to memory for what I heard concerning them.

The large male, Jung Pershad, must be close upon nine feet high, and the female, Suffa Kulli, at least seven feet; and I was astonished to find that they were the same that I had seen as little things in the Prince of Wales's collection in 1876. Suffa Kulli's age is not more than fifteen, yet she has been in a fair way of becoming a mother. There was no doubt as to the possibility, and she seemed to show some signs of it, but it ended in disappointment; however it is hoped that she will yet prove that these noble animals may be bred in captivity.

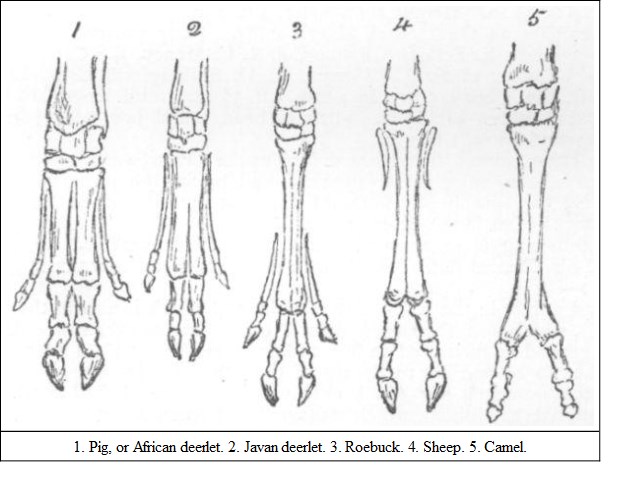

Osteology of the feet in Ruminantia, Artiodactyla .—The following illustrations were inadvertently omitted from the text in the section on the Artiodactyla.

Wild Boar, No. 434 .—A few days before leaving England, I called to say good-bye to an old friend well known in Calcutta and Lower Bengal, Dr. Charles Palmer. He asked me whether I had ever heard of a boar killing a tiger, and, on my answering in the affirmative, he told me he had just heard from his son, who had witnessed a fight between these two animals, in which the boar came off victorious, leaving his antagonist dead on the field.

Ovis Polii, No. 438 .—Mr. Carter in one of his letters to me says: "I see that you make the biggest horns of Ovis Polii 53 inches from tip to tip. In a photo of one brought down by the Yarkhand Expedition, which had a foot rule laid close, so as to scale it, the distance from tip to tip is nearly five feet."

I do not know which particular head is referred to, but two out of the three measurements given by me were of the finest heads brought down by the Expedition. There may have been a smaller pair with a wider spread, as the 73-inch horns I also mention, and which Sir Victor Brooke, to whom I sent a photograph, tells me is the finest head he has heard of, has only a spread of 48 inches.

Ovis cycloceros, No. 443 .—I gave from 25 to 30 inches as an average size for the horns of this species, but Captain W. Cotton, F.Z.S., writes to me that he sent home a pair of ovrial horns from Cabul, 35½ inches, and that there is a pair in the R.A. mess at Attock 38½ inches, but very thin. They were looted in the Jowaki campaign. This sheep has bred freely in the Zoological Society's Gardens, and two hybrids have been born there from a male of this species and the Corsican mouflon, Ovis musimon.

I mentioned that there is in the Gardens a specimen of Ovis Blanfordi. I see by the Society's list that this was presented by Captain Cotton; the habitat given is Afghanistan.

The Wild Goat of Asia Minor, No. 448 .—Mr. Carter writes to me: "In one of your letters you mention the Scind ibex, which is a wild goat. I have a photo of a head 31 inches round curve, but Mr. Inverarity, barrister, Bombay, says he has seen one 52½. The animal is not much bigger than the black buck." This last agrees with the estimate I formed from the specimens in the Indian Museum, Calcutta.

Tetraceros sub-quadricornutus, No. 463 .—It is doubtful whether Elliot's antelope should stand as a separate species; Blyth was against it, and Jerdon followed him, and I incline to think that it is only a variety. Dr. Sclater, to whom I mentioned the subject, appeared to me to agree in this view, but I see he includes it in his list of the Society's mammals. Being adverse to the multiplication of species, I gave it the benefit of the doubt, and included it with T. quadricornis; but, as I have received one or two letters from writers whose opinions are entitled to consideration, I mention them here, merely stating that I still feel inclined to doubt the propriety of promoting sub-quadricornutus to the dignity of a species. Dr. Gray was certainly of opinion it was separate; but then, great naturalist as he was, his peculiar foible was minute sub-division.

The claims of Elliot's antelope to separate rank are: absence of the anterior horns, or with only a trace; smaller size; lighter colour; but even the larger, darker quadricornis is sometimes without the anterior horns; and, unless some other marked difference is found in the skull, it is hardly sufficient to warrant separation. However, I will give what others say on the subject.

"I can scarcely agree with you as to Elliot's antelope not being a good species, I have therefore taken the trouble of having a most accurate and full-size sketch of the skull of one made, and if you will compare it with those of the ordinary quadricornis I think you will see a well-marked difference. Dr. Gray wrote to me, and said that there was the recognised species of sub-quadricornutus."—Letter from Mr. H. R. P. Carter, "Smoothbore" of the Field.

The following is an extract from a letter signed "Bheel," addressed to the editor of The Asian, which appeared in that paper:—

"In the jungles of Rajputana, especially about the Arravelli Range, I have shot repeatedly very small, exceedingly shy deer, called by the Bheels and shikaries in this part 'bhutar.' They are very much smaller than the four-horned antelope, having very sharp thin horns about two inches in length, which are perfectly smooth, as if polished, and black. The colour of the skin is light brown, somewhat like a chinkara, white inside the limbs and under the belly. The hair on the skin is short, smooth and glossy. The feet are exceedingly small, about one-third in size smaller than that of the four-horned antelope. They are very retiring little creatures, and very difficult to bag. They run, or, more appropriately, bound with amazing swiftness when disturbed, and disappear like some passing shadow. These little deer live on the lower spurs of the hills, and are generally found in pairs. They are very plump, and appear to be always in good condition. The last one I shot was last year. The females are hornless.

"The four-horned antelope is described accurately by Mr. Sterndale, only that, in my humble opinion, I do not consider it to be the smallest of the ruminant species. The 'Bheel' name for this creature is 'fonkra.' It is found in the thick jungles at the foot of the hills. It selects some secluded spot, which it does not desert when disturbed, returning invariably to its hiding-place when the coast is clear. I noticed this very particularly. The hair of the 'fonkra' is comparatively much longer than the bhutar's, and the colour is a great deal darker. Could Mr. Sterndale kindly let me know the Latin name for the 'bhutar'? I am sure it can't be Cervulus aureus (kakur, or barking deer), because the colour given of this deer is a beautiful bright glossy red or chesnut, while, as I have mentioned above, the colour of the bhutar is light brown."