полная версия

полная версияNatural History of the Mammalia of India and Ceylon

"Bheel's" "bhutar" is evidently Elliot's sub-quadricornutus.

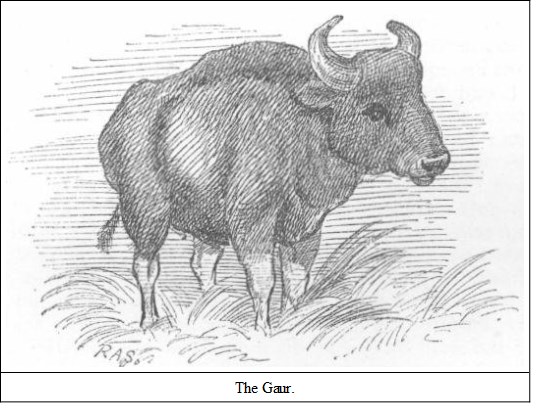

The Gaur, No. 464 .—Jerdon doubted the existence of this animal in the Himalayan Terai, according to Hodgson's assertion; but Hodgson was right, for I have a letter before me which I received some time back from Dr. W. Forsyth, stating that a few days previously a companion of his shot a large solitary bull (6 feet 1 inch at the shoulder) in the Terai, and he himself knocked one and lost another the day before he wrote. The local name is gauri-gai.

I also received a letter through the columns of The Asian from "Snapshot," vouching for the existence of the gaur in the Darjeeling Terai.

Another correspondent of The Asian writes regarding the naming of this species:—

"In referring to Mr. Sterndale's descriptions of the gaur and gayal, in your issues of the 28th March and 11th April, I trust that that gentleman will not be offended by my making a few remarks on the subject, and that he will set me right if I am in the wrong. I see that he has perpetuated what appears to my unscientific self a mistake on the part of the old writers—Colebrooke, Buchanan, Trail, and others, who I fancy got confused, and mixed up the animals. The local name for the Central Indian ox is over a large tract of country the gayal, or gyll; and this, being the animal with the peculiar frontal development, was most probably named bos, or Gavæus frontalis, whilst the mithun, or Eastern Bengal animal, was the gaur. It seems to me, therefore, that the names should be transposed. Will Mr. Sterndale consider this, if he has not already done so; and, if I am wrong, tell me why the animal with peculiar frontal development, and called the gayal locally, should not have been named frontalis, whilst the animal called mithun, with nothing peculiar in his frontal development, is so called?

"Orissa, April 15th, 1882.

"CHAMPSE.

"P.S.—Do any of the Eastern Bengal races call this mithun gayal?"

I think Hodgson's name Bibos cavifrons is a sufficient proof that Gavæus gaurus is applicable to the animal with the high frontal crest, which is the species inhabiting the Himalayan Terai, and is locally known as the gaur, or gauri-gai. It is known as gayal in some parts of India, but, where the people are familiar with the mithun, the gaur is called asl'gayal, from whence Horsfield's name Bibos asseel. Probably the mithun was called frontalis, under ignorance of a species with a still greater frontal development.

Gavæus frontalis interbreeds freely with domesticated cattle of all kinds. In the Society's Gardens are several hybrids between this and Bos Indicus, one of which hybrids again interbred with American bison (Bison Americanus), the progeny being one-half bison, and one-quarter each frontalis and Indicus.

APPENDIX D

As many specimens are spoilt by either insufficient curing, or curing by wrong methods, I have asked Mr. Geo. F. Butt, F.Z.S., who was for many years manager to Edwin Ward, whom he has now succeeded, to give me a page or two of useful hints on the preservation of skins. The following notes are what he has kindly placed at my disposal. I know of no one I can more strongly recommend for good work than Mr. Butt. Some of his groups are works of art, with most lifelike finish. I have just seen a bear set up by him which seems almost to breathe.

NOTES ON SKINNING THE MAMMALIA AND THE PRESERVATION OF SKINS. By GEO. F. BUTT, F.Z.S., Naturalist to the Royal Family, 49, Wigmore Street, London, W.

The quadruped killed, the first and important step is to plug up the nostrils and throat with cotton-wool or tow, as also any wound from which blood may escape. Place the animal on its back, make a longitudinal incision with the knife at the lower part of the belly (the vent), and thence in as straight a line as possible extending to the chin bone, taking particular care that during the operation the hair is carefully divided and not cut. Vertical incisions may then be made extending down the inside of each leg to the claws. The skin can then be turned back in every direction as far as the extent of the incisions will admit of—the legs may now be freed from the skin. Next make a straight incision down the under part of the tail to the tip, turn the skin back until it is free. Having executed this, there remains only to remove the skin from the back and head; to do this place the carcase on its side, and with the scalpel carefully separate the skin by drawing it towards the head, in skinning which care being taken to cut the ears as close to the skull as possible, leaving the cartilage in the skin; the eyelids, also nose and lips, should be carefully skinned without injury. The skin is now free from the carcase. Turn the ears inside out, the nostrils, lips, and feet, removing all cartilage and flesh.

Place the skin open on the ground with the fur side down, and remove the flesh and pieces of fat adhering; scrape the skin well, so as to get away all the loose particles of under-skin or pelt. When this has been thoroughly done, take powdered alum plentifully, and, with a very small quantity of common salt, rub well into the skin, especially into the ears, nostrils, lips, and feet, so that every portion of the skin is powerfully impregnated. Allow the skin to lie in this condition for an hour or so, then place it on a line or branch to dry. The operation should be carried on in the shade, if possible.

If the specimen is not for stuffing it may be pegged out to dry on the ground, but in no one instance should a skin be unduly strained out of shape, which is often done in order to make it appear larger than it really is, a mistake which is very common.

When this operation is completed, and the skin dry, it is ready for packing, and should be folded, with the fur or hair inside, and placed in a sound box or case well protected against the visits of ants, beetles, or moth.

Where it is intended that the animal should be ultimately stuffed whole, it is necessary to preserve the leg bones. These should be separated from the trunk at the os humeri or shoulder-joint, and at the os femoris or thigh bones; these bones cleanse from flesh.

The skull in every instance should be preserved: remove the flesh and brain; to do this place the skull in boiling water for five or ten minutes—in the case of small skulls for five minutes only, care being taken that the teeth are not lost. In packing skulls each one should be tied up in paper, marked with a corresponding number to the skin to which it belongs, and packed firmly, to prevent rolling about, the result of which is often broken teeth and disappointment.

Another excellent method for the preservation of skins of mammalia, where convenience will permit, and which can be followed with confidence, is as follows: After the skin has been treated according to the directions given—viz. thoroughly scraped and cleansed of all adherent particles of flesh, &c.—place it entirely in a tub or cask in which a solution or pickle has been previously prepared, as follows: to every gallon of cold water add 1 lb. powdered alum, ½ oz. saltpetre, 2 oz. common salt; well mix. Allow the skin to remain about a couple of days, after which hang it up to dry and for packing.

1

There has been lately exhibited in London a child from Borneo which has several points in common with the monkey—hairy face and arms, the hair on the fore-arm being reversed, as in the apes.

2

Since the above was written there has been published in the 'Journal of the Anthropological Institute,' vol. xii., a most interesting and exhaustive paper on these people by Mr. E. H. Man, F.R.G.S., giving them credit for much intelligence.

3

There is an excellent coloured drawing by Wolf of these two Gibbons in the 'Proceedings of the Zoological Society,' 1870, page 86, from which I have partly adapted the accompanying sketch.

4

The legend, with native picture, is given in Wilkin's 'Hindoo Mythology.'

5

Mr. J. Cockburn, of the Imperial Museum, has, since I wrote about the preceding species, given me some interesting information regarding the geographical distribution of Presbytes entellus and Hylobates hooluck. He says: "The latter has never been known to occur on the north bank of the Brahmaputra, though swarming in the forests at the very water's edge on the south bank. The entellus monkey is also not found on the north bank of the Ganges, and attempts at its introduction have repeatedly failed." P. schistaceus replaces it in the Sub-Himalayan forests.

6

On referring to Mr. Sanderson's interesting book, 'Thirteen Years among the Wild Beasts of India,' and General Shakespear's 'Wild Sports,' I find that both those authors corroborate my assertion that the sloth bear is deficient in the sense of hearing. Captain Baldwin, however, thinks otherwise; but the evidence seems to be against him in this respect.

7

Since writing the above, the following letter appeared in The Asian of May 11, 1880:—

"THE HIMALAYAN BLACK BEAR"SIR,—Mr. Sterndale, in the course of his interesting papers on the Mammalia of British India, remarks of Ursus Tibetanus, commonly known as the Himalayan Black Bear, that 'a wounded one will sometimes show fight, but in general it tries to escape.' This description is not, I think, quite correct. As it would lead one to suppose that this bear is not more savage than any other wild animal—the nature of most of the feræ being to try to escape when wounded, unless they see the hunter who has fired at them, when many will charge at once, and desperately. The Himalayan Black Bear will not only do this almost invariably, but often attacks men without any provocation whatever, and is altogether about the most fierce, vicious, dangerous brute to be met with either in the hills or plains of India. They inflict the most horrible wounds, chiefly with their paws, and generally—as Mr. Sterndale states—on the face and head. I have repeatedly met natives in the interior frightfully mutilated by encounters with the Black Bear, and cases in which Europeans have been killed by them are by no means uncommon. These brutes are totally different in their dispositions to the Brown Bear (Ursus Isabellinus), which, however desperately wounded, will never charge. I believe there is no case on record of a hunter being charged by a Brown Bear; or even of natives, under any circumstances, being attacked by one; whereas every one of your readers who has ever marched in the Himalayas must have come across many victims of the ferocity of Ursus Tibetanus. As I said before, this brute often, unwounded, attacks man without any provocation whatever. Two cases that I know of myself may not be without interest. An officer shooting near my camp was stalking some thar. He was getting close to them, when a Black Bear rushed out at him from behind a large rock on his right and above him. He was so intent on the thar, and the brute's rush was so sudden, that he had barely time to pull from the hip, but he was fortunate enough to kill the animal almost at his feet. I heard this from him on the morning after it happened. On another occasion, I was shooting in Chumba with a friend. One evening he encamped at a village, about which there was, as usual, a little cultivation on terraces, and a good many apricot-trees. Lower down the khud there was dense jungle. The villagers told us that a Black Bear had lately been regularly visiting these trees, and generally came out about dusk, so that if we would go down and wait, we should be pretty sure of a shot. We went, and took up positions behind trees, about 200 yards apart, each of us having a man from the village with us. Intervening jungle prevented us from seeing each other. I had not been at my post more than ten minutes when I was startled by loud shrieks and cries from the direction of my companion. No shot was fired, and the coolie with me said that the bear had killed some one. In less than a minute I had reached the spot where I had left my friend. He, and the man with him, had disappeared; but, guided by the shrieks, which still continued, I made my way into the thick cover in front of his post, and about fifty yards inside it, much to my relief, came upon him, rifle in hand, standing over the dead body of a man, over which two people—the coolie that had been with my friend and an old woman—were weeping, and shrieking loudly, 'Look out!' said he, as I came up, 'the bear has just killed this fellow!' The first thing to be done was to carry him out into the open. I helped to do this, and directly I touched him I felt that he was stone cold, and a further examination showed he must have been dead some hours. That he had been killed by a bear was also very evident. He was naked to the waist, and had been cutting grass. His bundle lay by him, and the long curved kind of sickle that the hillmen used to cut grass with was stuck in his girdle, showing that he had not had time to draw it to strike one blow in his defence. The mark of the bear's paw on his left side was quite distinct. This had felled him to the ground, and then the savage brute had given him one bite—no more, but that one had demolished almost the whole of the back of his head, and death must have been instantaneous. The man had apparently cut his load of grass, and was returning with it to the village, when he disturbed the bear, which attacked him at once. The old woman was his mother, and the coolie with J– some relation. Her son having been away all day, I suppose the old woman had gone to look for him. She found his body, as described, just below J–'s post, and at once set up a lamentation which brought the coolie, J–'s attendant, down to her, and J– following himself, thought at first that the man had been killed then and there. There was such a row kicked up that no bear came near the apricots that night, and the next day we had to march, as our leave was up. I have heard of many other cases of the Black Bear attacking without any provocation, and from what I know of the brute I quite believe them; and, after all, the animal is not worth shooting. Their skins are always poor and mangy, and generally so greasy that they are very difficult to keep until you can make them over to the dresser. The skin of the Snow or Brown Bear, on the other hand, particularly if shot early in the season, is a splendid trophy, and forms a most beautiful and luxurious rug, the fur being extremely soft, and several inches in depth.

"SPINDRIFT."8

In the same year were sold by other firms, 22,000 otter skins and 4500 sables. See Appendix C for further statistics.

9

In fact it was his quotation that induced me to buy a copy of that most charming little book, which I recommend every one to read.—R. A. S.

10

At Mr. Shillingford's request, I made over this skull to the Calcutta Museum.

11

Since writing the above I have to thank "Meade Shell" for the measurements of the skull of a tiger 11 ft. 6 in. The palatal measurement is 12 inches, which, according to my formula, would give only 10 ft. 8 in.; but it must be remembered that I have allowed only 3 ft. for the tail, whereas such a tiger would probably have been from 3½ to 4 ft., which would quite bring it up to the length vouched for. The tail of a skeleton of a much smaller tiger in the museum measures 3 ft. 3½ in., which with skin and hair would certainly have been 3½ ft. Until sportsmen begin to measure bodies and tails separately it will, I fear, be a difficult matter to fix on any correct formula.—R. A. S. See Appendix C.

12

'Seonee.'

13

'Seonee.'

14

Milne-Edwards describes this animal in his 'Recherches sur les Mammifères,' page 341.

15

Both reputed to be untameable.

16

I can bear witness to this, having lately made his acquaintance.

17

Cuvier's name for P. musanga.—R. A. S.

18

The Tipari of Bengal.—R. A. S.

19

See Appendix B for illustration.

20

A Chinese species: Western China, Formosa and Hainau.—R. A. S.

21

I advise half water in the case of cow's milk, or one quarter water with buffalo milk.—R. A. S.

22

Dallas mentions (Cassell's 'Nat. Hist.') a species from Kumaon, Cricetus songarus.

23

Since writing the above, Dr. Anderson has kindly allowed me to examine the specimens of Mus concolor in the museum, and in the adult state they are considerably more rufescent. In one specimen, allowing for the effects of the spirit, the fur was a bright rufescent brown; but, whatever be the tint of the prevailing colour, it pervades the whole body, being but slightly paler on the under-parts. Size, about 4 inches; tail, about 4½ inches.—R. A. S.

24

See Appendix A for description and dentition of Myoxus.

25

In this case probably parents and young.

26

Nesokia providens.

27

Nesokia Blythiana.

28

Formerly Jaculinæ.

29

See note in Appendix C on this subject.

30

There are some interesting notes on the dentition of the rhinoceros, especially in abnormal conditions, by Mr. Lydekker in the 'J. A. S. B.' for 1880, vol. xlix., part ii.

31

There is a very interesting letter in The Asian for July 20, 1880, p. 109, from Mr. J. Cockburn, about R. Sumatrensis, of which he considers R. lasiotis merely a variety. He says it has been shot in Cachar.—R. A. S.

32

See notes in Appendix C.

33

It must be remembered that at such great elevations a camel is unable to bear a very heavy load.

34

See notes to Ovis Polii in Appendix C.

35

Ovis Heinsi and Ovis nigromontana are doubtful species allied to the foregoing, and are not found within the limits assigned to this work.

36

See also Appendix C.

37

Colonel Kinloch writes on my remarks as above, and gives the following interesting information: "I cannot consider the spiral-horned and the straight-horned markhor to be one species, any more than the Himalayan and Sindh ibex. The animals differ much in size, habits, and coat, as well as in the shape of their horns. Mr. Sterndale considers that the markhor is probably the origin of some of our breeds of domestic goats, and states that he has seen tame goats with horns quite of the markhor type. Has he ever observed that (as far as my experience goes) the horns of domestic goats invariably twist the reverse way to those of markhor? I have observed that the horns of not only markhor, but also antelope, always twist one way; those of domestic goats the other."

38

These are wanting.—R. A. S.

39

See notes in Appendix C.

40

The true bison has fourteen pairs of ribs.—R. A. S.

41

The third tiger is one which Sir Charles Reid has had set up, and is now in his house; it measured, as he lay on the ground, 10 ft. 6 in. He then goes on to say that his father-in-law had killed in the Dhoon four or five tigers over 11 feet, and that the late Sir Andrew Waugh told him he had killed one in the same place 13 feet. He says: "I believe the Dhoon tigers are the largest and finest beasts that are found in any part of India." Their coats are longer and thicker also.