полная версия

полная версияNatural History of the Mammalia of India and Ceylon

Hodgson was apparently not well acquainted at the time with saiga, or he would have certainly alluded to the affinity. Kinloch has the following regarding its habits:—

"In Chang Chenmo, where I have met with it, the elevation can be nowhere less than 14,000 feet, and some of the feeding grounds cannot be less than 18,000. In the early part of summer the antelope appear to keep on the higher and more exposed plains and slopes when the snow does not lie; as the season becomes warmer, the snow, which has accumulated on the grassy banks of the streams in the sheltered valleys, begins to dissolve, and the antelope then come down to feed on the grass which grows abundantly in such places, and then is the time when they may easily be stalked and shot. They usually feed only in the mornings and evenings, and in the day-time seek more open and elevated situations, frequently excavating deep holes in the stony plains, in which they lie, with only their heads and horns visible above the surface of the ground. It is a curious fact that females are rarely found in Chang Chenmo; I have met with herds of sixty or seventy bucks, but have only seen one doe to my knowledge during the three times that I visited the valley."

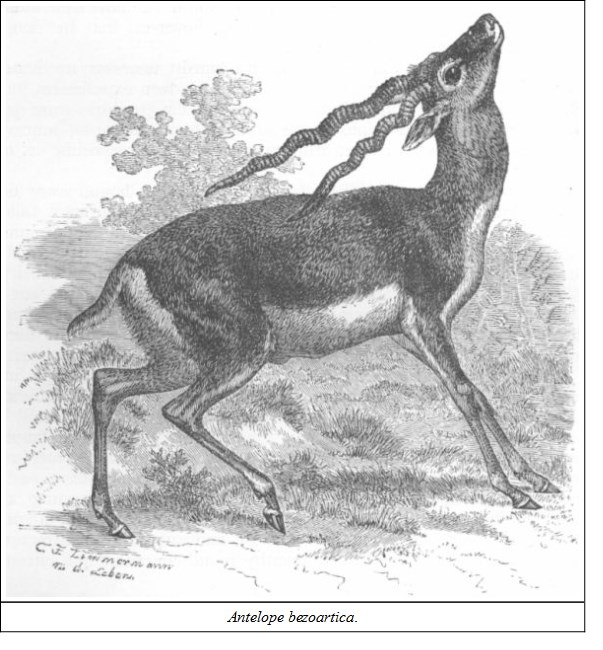

GENUS ANTELOPE (restricted)Horns in the male only; abnormal cases of horned females are on record, but they only prove the rule. No muffle; sub-orbital sinus moderate, somewhat linear; no canines; groin-pits large; feet-pits present. In the skull the sub-orbital fossa is large.

NO. 461. ANTELOPE BEZOARTICAThe Indian Antelope (Jerdon's No. 228)NATIVE NAMES.—Mrig or Mirga, Sanscrit; Harna, Hirun, Harin (male) and Hirni (female), Hindi; also Kalwit, Hindi, according to Jerdon; Goria (female) and Kala (male), in Tirhoot; Kalsar (male) and Baoti (female), in Behar; Bureta, in Bhagulpore; Barout and Sasin, in Nepal; Phandayet, Mahrathi (Jerdon). Hiru and Bamuni-hiru, Mahrathi; Chigri, Canarese; Irri (male), Sedi (female), and Jinka, Telegu; Alali (male) and Gandoli (female), of Baoris.

HABITAT.—In open plain country throughout India except in Lower Bengal and Malabar. In the Punjab it does not cross the Indus. Dr. Jerdon says: "I have seen larger herds in the neighbourhood of Jalna in the Deccan than anywhere else—occasionally some thousands together, with black bucks in proportion. Now and then, Dr. Scott informs me, they have been observed in the Government cattle-farm at Hissar in herds calculated at 8000 to 10,000." I must say I have never seen anything like this, although in the North-west, between Aligarh and Delhi, I have noticed very large herds; in the Central provinces thirty to forty make a fair average herd, though smaller ones are more common. These small parties generally consist of does, and perhaps two or three young sandy bucks lorded over by one old black buck, who will not allow any other of his colour to approach without the ordeal of battle. I have lately heard of them in Assam, but forget the precise locality.

DESCRIPTION.—Form supple and elegant, with graceful curves; the neck held up proudly; the head adorned with long, spiral, and closely annulated horns, close at the base, but diverging at the tips in a V form. In very large specimens there are five flexures in the horn, but generally four. They are perfectly round, and taper gradually to the tips, which are smooth; the bony cores are also spiral, so that in the dry skull the horn screws on and off. The colour of the old males is deep blackish-brown, the back and sides with an abrupt line of separation from the white of the belly; the dark colour also extends down the outer surface of the limbs; the back of the head, nape and neck are hoary yellowish; under parts and inside of limbs pure white; the face is black, with a white circle round the eyes and nose; the tail is short; the young males are fawn-coloured. The females are hornless, somewhat smaller, and pale yellowish-fawn above, white below, with a pale streak from the shoulder to the haunch.

SIZE.—Length, about 4 feet to root of tail; tail, 7 inches; height at shoulder, 32 inches. Horns, average length about 20 inches—fine ones 22, unusual 24, very rare 26. Sir Barrow Ellis has or had a pair 26½, with only three flexures; 28 has been recorded by "Triangle" in The Asian, and 30 spoken of elsewhere, but I have as yet seen no proof of the latter. The measurement should be taken straight from base to tip, and not following the curves of the spiral. I have shot some a little over 22, but never more. I believe, however, that the longest horns come from the North-west.

This antelope is so well known that it is hardly necessary to dilate at length on it; every shikari in India has had his own experiences, but I will take from Sir Walter Elliot's account and Dr. Jerdon's some paragraphs concerning the habits of the animal which cannot be improved upon, and add a short extract from my own journals regarding its love of locality:—

"When a herd is met with and alarmed, the does bound away for a short distance, and then turn round to take a look; the buck follows more leisurely, and generally brings up the rear. Before they are much frightened they always bound or spring, and a large herd going off in this way is one of the finest sights imaginable. But when at speed the gallop is like that of any other animal. Some of the herds are so large that one buck has from fifty to sixty does, and the young bucks driven from these large flocks are found wandering in separate herds, sometimes containing as many as thirty individuals of different ages.

"They show some ingenuity in avoiding danger. In pursuing a buck once into a field of toor, I suddenly lost sight of him, and found, after a long search, that he had dropped down among the grain, and lay concealed with his head close to the ground. Coming on another occasion upon a buck and doe with a young fawn, the whole party took to flight, but the fawn being very young, the old ones endeavoured to make it lie down. Finding, however, that it persisted in running after them, the buck turned round and repeatedly knocked it over in a cotton field until it lay still, when they ran off, endeavouring to attract my attention. Young fawns are frequently found concealed and left quite by themselves."—Elliot.

Jerdon adds: "When a herd goes away on the approach of danger, if any of the does are lingering behind, the buck comes up and drives them off after the others, acting as whipper-in, and never allowing one to drop behind. Bucks may often be seen fighting, and are then so intently engaged, their heads often locked together by the horns, that they may be approached very close before the common danger causes them to separate. Bucks with broken horns are often met with, caused by fights; and I have heard of bucks being sometimes caught in this way, some nooses being attached to the horns of a tame one. I have twice seen a wounded antelope pursued by greyhounds drop suddenly into a small ravine, and lie close to the ground, allowing the dogs to pass over it without noticing, and hurry forward." ('Mamm. of India,' p. 278.)

I have myself experienced some curious instances of the hiding propensities spoken of by Sir Walter Elliot and Dr. Jerdon. In my book on Seonee I have given a case of a wounded buck which I rode down to the brink of a river, when he suddenly disappeared. The country was open, and I was so close behind him that it seemed impossible for him to have got out of sight in so short a space of time; but I looked right and left without seeing a trace of him, and, hailing some fishermen on the opposite bank, found that they had not seen him cross. Finally my eye lighted on what seemed to be a couple of sticks projecting from a bed of rushes some four or five feet from the bank. Here was my friend submerged to the tip of his nose, with nothing but the tell-tale horns sticking out.

This antelope attaches itself to localities, and after being driven away for miles will return to its old place. The first buck I ever shot I recovered, after having driven him away for some distance and wounded him, in the very spot I first found him; and the following extract from my journals will show how tenaciously they cling sometimes to favourite places:—

"I was out on the boundary between Khapa and Belgaon, and came across a particularly fine old buck, with very wide-spreading horns; so peculiar were they that I could have sworn to the head amongst a thousand. He was too far for a safe shot when I first saw him, but I could not resist the chance of a snap at him, and tried it, but missed; and I left the place. My work led me again soon after to Belgaon itself, and whilst I was in camp there I found my friend again; but he was very wary; for three days I hunted him about, but could not get a shot. At last I got my chance; it was on the morning of the day I left Belgaon, I rode round by the boundary, when up jumped my friend from a bed of rushes, and took off across country. I followed him cautiously, and found him again with some does about two miles off. A man was ploughing in the field close by; so, hailing him, I got his bullocks and drove them carefully up past the does. We splashed through a nullah, and waded through a lot of rushes, and at last I found myself behind a clump of coarse grass, with a nullah between me and the antelope. They jumped up on my approach, and Blacky, seeing his enemy, made a speedy bolt of it; but I was within easy range of him, and a bullet brought him down on his head with a complete somersault. Now this buck, in spite of the previous shot at him, and being hunted about from day to day, never left his ground, and used to sleep every night in a field near my tent."

This antelope has been raised by the Hindoos amongst the constellations harnessed to the chariot of the moon. Brahmins can feed on its flesh under certain circumstances prescribed by the 'Institutes of Menu,' and it is sometimes tamed by Fakirs. It is easily domesticated, but the bucks are always dangerous when their horns are full grown, especially to children. The breeding season begins in the spring, but fawns of all ages may be seen at any time of the year. The flesh of this species is among the best of the wild ruminants.

The next group of antelopes are those with smooth horns, without knots; spiral in some African species, but short and straight, or but slightly curved in the Indian ones. Females hornless. There are but two genera in India, Portax and Tetraceros.

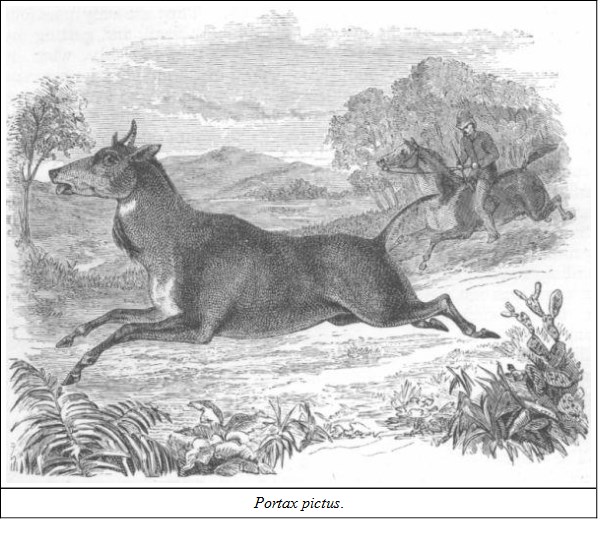

GENUS PORTAX—THE NYLGAOHorns on back edge of frontal bone behind the orbit, short, recurved, conical and smooth, angular at the base; bovine nose with large moist muffle; small eye-pits; hind legs shorter than the front; tail long and tufted; back short, sloping down from high withers; the neck deep and compressed like a horse, with a short upright mane; on the throat of the male under a white patch is a long tuft of black hair. In the skull the nasal opening is small, and the molars have, according to Dr. Gray, supplementary lobes. Dr. Jerdon says: "There is a small pit in front of the orbit, and anterior to this a small longitudinal fold, in the middle of which there is a pore through which exudes a yellow secretion from the gland beneath."

The female has sometimes in an abnormal condition been found with horns. Mr. J. Cockburn, in a letter to The Asian (11th of November, 1879, p. 40), describes such a one.

NO. 462. PORTAX PICTUS vel TRAGOCAMELUSThe Nylgao or Blue Bull (Jerdon's No. 226)NATIVE NAMES.—Nilgao, Nilgai, or Lilgao, Lilgai, Rojra or Rojh, Rooi (female), Hindi; Guraya, Gondi; Maravi, Canarese; Manupotu, Telegu.

HABITAT.—India generally, from the Himalayas to the south. It is not common south of the Ganges, nor, according to Jerdon, is it found in the extreme south of India.

DESCRIPTION.—A horse-like animal at the first glance, owing to its lean head, long, flat, and deep neck, and high withers, but with cervine hind-quarters, lower than in front. The male is of an iron grey colour, intensified by age; the inside of the ears, lips, and chin are white; a large white patch on the throat, below which is the pendant tuft of black hair; the chest, stomach, and rings on the fetlocks, white; mane, throat-tuft and tip of tail, black. The female is a sandy or tawny colour, and is somewhat smaller than the male.

SIZE.—Length of male, 6½ to 7 feet; tail 18 to 22 inches; height at shoulder, from 13 to 14½ hands; horns, from 8 to 10 inches.

The nilgao inhabits open country with scrub or scanty tree jungle, also, in the Central provinces, low hilly tracts with open glades and valleys. He feeds on beyr (Zizyphus jujuba) and other trees, and at times even devours such quantities of the intensely acrid berries of the aonla (Phyllanthus emblica) that his flesh becomes saturated with the bitter elements of the fruit. This is most noticeable in soup, less so in a steak, which is at times not bad. The tongue and marrow-bones, however, are generally as much as the sportsman claims, and, in the Central provinces at least, the natives are grateful for all the rest.

He rests during the day in shade, but is less of a nocturnal feeder than the sambar stag. I have found nilgao feeding at all times of the day. The droppings are usually found in one place. The nilgao drinks daily, the sambar only every third day, and many are shot over water. Although he is such an imposing animal, the blue bull is but poor shooting, unless when fairly run down in the open. With a sharp spurt he is easily blown, but if not pressed will gallop for ever. In some parts of India nilgai are speared in this way. I myself preferred shooting them either from a light double-barrelled carbine or large bore pistol when alongside; the jobbing at such a large cow-like animal with a spear was always repugnant to my feelings. They are very tenacious of life. I once knocked one over as I thought dead, and, putting my rifle against a tree, went to help my shikaree to hallal him, when he jumped up, kicked us over, and disappeared in the jungle; I never saw him again. A similar thing happened to a friend who was with me, only he sat upon his supposed dead bull, quietly smoking a cigar and waiting for his shikarees, when up sprang the animal, sending him flying, and vanished. On another occasion, whilst walking through the jungle, I came suddenly on a fine dark male standing chest on to me. I hardly noticed him at first; but, just as he was about to plunge away into the thicket, I rapidly fired, and with a bound he was out of sight. I hunted all over the place and could find no trace of him. At last, by circling round, I suddenly came upon him at about thirty yards off, standing broadside on. I gave him a shot and heard the bullet strike, but there was not the slightest motion. I could hardly believe that he was dead in such a posture. I went up close, and finally stopped in front of him; his neck was stretched out, his mouth open and eyes rolling, but he seemed paralysed. I stepped up close and put a ball through his ear, when he fell dead with a groan. I have never seen anything like it before or since, and can only suppose that the shot in the chest had in some way choked him. I have alluded to this incident in my book on Seonee; it was in that district that it occurred.

The nilgao is the only one of the deer and antelope of India that could be turned to any useful purpose. The sambar stag, though almost equal in size, will not bear the slightest burden, but the nilgao will carry a man. I had one in my collection of animals which I trained, not to saddle, for such a thing would not stay on his back, but to saddle-cloth. He was a little difficult to ride, rather jumpy at times, otherwise his pace was a shuffling trot. I used to take him out into camp with me, and made him earn his grain by carrying the servants' bundles. He was not very safe, for he was, when excited, apt to charge; and a charge from a blue bull with his short sharp horns is not to be despised. In some parts the Hindoos will not touch the flesh of this animal, which they believe to be allied to the cow. It has much more of a horsey look about it. McMaster says that in some parts of the Coimbatore district the natives described this creature to Colonel Douglas Hamilton as a wild horse, and called it by a name signifying such. He also notices the resemblance of the Gondi name Guraya, to the Hindi Ghora.

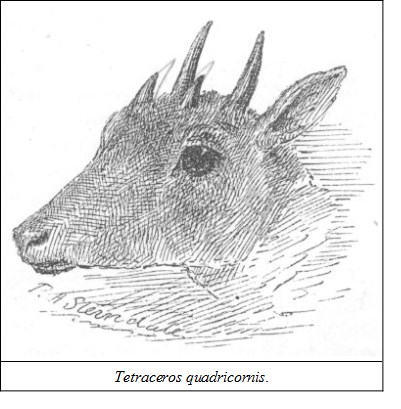

GENUS TETRACEROSHorns four, conical, smooth, slightly bent forward at tip, the anterior ones very short, sometimes rudimentary, which has led to the distinction of a separate species by some naturalists; slightly ringed at the base. The posterior ones situated far back on the frontal bone, the anterior ones above the orbits; eye-pits small, linear; muffle large; feet-pits in the hind feet; no groin-pits; four mammæ; canine teeth in the males; females hornless. The skull is characterized by the large sub-orbital fossæ which occupy nearly the whole cheek. The various species—sub-quadricornutus of Elliot, iodes and paccerois of Hodgson—are but varieties of the following only Indian species.

NO. 463. TETRACEROS QUADRICORNISThe Four-horned Antelope (Jerdon's No. 227)NATIVE NAMES.—Chowsingha, Chowka. Jerdon also gives Bherki, Bekra, and Jangli-bakra, but I have also heard these names given by natives to the rib-faced deer (Cervulus aureus); Bhir-kura (the male) and Bhir(female) Gondi; Bhirul of Bheels; Kotri, Bustar; Kond-guri, Canarese; Konda-gori, Telegu (Jerdon). Kinloch also gives Doda, Hindi.

HABITAT.—Throughout India, but not in Ceylon or Burmah.

DESCRIPTION.—A small brownish-bay animal, slightly higher at the croup than at the shoulder, which gives it a poky look, lighter beneath and whitish inside the limbs and in the middle of the belly; fore-legs, muzzle, and edge of ears dark; fetlocks dark, sometimes ringed with lighter colour. The colouring varies a good deal. The horns are situated as I have before described; the anterior ones are subject to much variation; sometimes they are absent or represented merely by a black callous skin; others are merely little knobs; the largest seldom exceed an inch and a-half, and the posterior horns five inches.

SIZE.—Head and body, 40 to 42 inches; height at shoulder, 24 to 26 inches; at croup a little higher.

This little antelope, the smallest of Indian hollow-horned ruminants, is very shy and difficult to get, even in jungles where it abounds. It was plentiful in the Seonee district, yet I seldom came across it, and was long before I secured a pair of live ones for my collection. It frequents, according to my experience, bamboo jungle; but, according to Kinloch, Jerdon and other writers, it is found in jungly hills and open glades, in the forests, and in bushy ground near dense forests.

It is an awkward-looking creature in action, as it runs with its neck stuck out in a poky sort of way, making short leaps; in walking it trips along on the tips of its toes like the little mouse-deer (Meminna). The young are stated to be born in the cold season. General Hardwicke created great confusion for a time by applying the name chikara, which is that of the Gazella Bennetti, to this species. It is not good eating, but can be improved by being well larded with mutton fat when roasted. McMaster believes in the individuality of Elliot's antelope (T. sub-quadricornutus), but more evidence is required before it can be separated from quadricornis. The mere variation in size, or the presence or absence of the anterior horns and the lighter shade of colour, are not sufficient reasons for its separation as a species, for the quadricornis is subject to variation in like manner.39

BOVINÆ—CATTLEThese comprise the oxen, and wind up the hollow-horned ruminants as far as India is concerned. There are in the New World some other very interesting animals of this group, such as the musk-ox (Ovibos), and the prong-horned antelope (Antilocapra), which last so far resembles the Cervidæ that the horns, which are bifurcate, are also annually shed. They come off the bony core, on which the new horn is already beginning to form.

The Bovines are animals of large size, horned in both sexes, a very large and broad moist muffle, massive bodies and stout legs. The horns, which are laterally wide spread, are supported on cores of cellular bone, and are cylindrical or depressed at the base. The nose broad, with the nostrils at the side. The skull has no sub-orbital pit or fissure, and the bony orbit is prominent; grinders with a well-developed supplementary lobe; cannon bone short. In India, the groups into which this sub-family may be divided, are oxen, the buffaloes, and the yaks. There are no true bison in our limits, the commonly so-called bison being properly a wild ox. The taurine or Ox group is divided into the Zebus, or humped domestic cattle; Taurus, humpless cattle with cylindrical horns; and Gavæus, humpless cattle with flattened horns.

According to Dr. Jerdon, in some parts of India small herds of zebus have run wild. He says:—

"Localities are recorded in Mysore, Oude, Rohilkund, Shahabad, &c., and I have lately seen and shot one in the Doab near Mozuffernugger. These, however, have only been wild for a few years. Near Nellore, in the Carnatic, on the sea-coast there is a herd of cattle that have been wild for many years. The country they frequent is much covered with jungle and intersected with salt-water creeks and back-waters, and the cattle are as wild and wary as the most feral species. Their horns were very long and upright, and they were of large size. I shot one there in 1843, but had great difficulty in stalking it, and had to follow it across one or two creeks."

GENUS GAVÆUSMassive head with large concave frontals, surmounted in G. gaurus by a ridge or crest of bone; horns flattened on the outer surface, corrugated at the base, and smooth for the rest of the two-thirds, or a little more; wide-spreading and recurved at the tips, forming a crescent; greenish grey for the basal half, darker towards the tips, which are black; muffle small; dewlap small or absent; the spinous processes of the dorsal vertebræ are greatly developed down to about half the length of the back; legs small under the knee, and white in colour; hoofs small and pointed, leaving a deer-like print in the soil, very different to the splay foot of the buffalo.

NO. 464. GAVÆUS GAURUSThe Gaur, popularly called Bison (Jerdon's No. 238)NATIVE NAMES.—Gaor or Gaori-gai, Bun-boda, Hindi; Boda and Bunparra in the Seonee and Mandla districts; Pera-maoo of Southern Gonds; Gaoiya, Mahrathi; Karkona, Canarese; Katuyeni, Tamil; Jangli-kulgha in Southern India; Pyoung in Burmah; Salandang in the Malay countries. Horsfield gives the following names under his Bibos asseel: As'l Gayal, Hindi; Seloi, Kuki; P'hanj of the Mughs and Burmese, and some others which he considers doubtful.

HABITAT.—Regarding this, I quote at length from Jerdon, whose inquiries were carefully made. He says: "The gaur is an inhabitant of all the large forests of India, from near Cape Comorin to the foot of the Himalayas. On the west coast of India it is abundant all along the Syhadr range on Western Ghâts, both in the forests at the foot of the hills, but more especially in the upland forests and the wooded country beyond the crest of the Ghâts. The Animally hills, the Neilgherries, Wynaad, Coorg, the Bababooden hills, the Mahableshwar hills, are all favourite haunts of this fine animal. North of this, it occurs to my own knowledge in the jungles on the Taptee river and the neighbourhood, and north of the Nerbudda; a few on the deeper recesses of the Vindhian mountains. On the eastern side of the peninsula it is found in the Pulney and Dindigul hills, the Shandamungalum range, the Shervaroys, and some of the hill ranges near Vellore and the borders of Mysore. North of this, the forest being too scanty, it does not occur till the Kistna and Godavery rivers; and hence it is to be found in suitable spots all along the range of Eastern Ghâts to near Cuttack and Midnapore, extending west far into Central India, and northwards towards the edge of the great plateau which terminates south of the Gangetic valley. According to Hodgson it also occurs in the Himalayan Terai, probably however only towards the eastern portion, and here it is rare, for I have spoken to many sportsmen who have hunted in various parts of the Terai, from Sikhim to Rohilkund, and none have ever come across the gaur at the foot of the Himalayas."—'Mam. of Ind.,' p. 303. (See also Appendix C.)