полная версия

полная версияNatural History of the Mammalia of India and Ceylon

Horns of the rusine type, but with the tres-tine longer than the royal or posterior tine; beam much bent; horns paler and smoother than in the sambar; large muffle and eye-pits; canines moderate; feet-pits in the hind-feet only; also groin-pits; tail of moderate length; skin spotted with white; said to possess a gall-bladder.

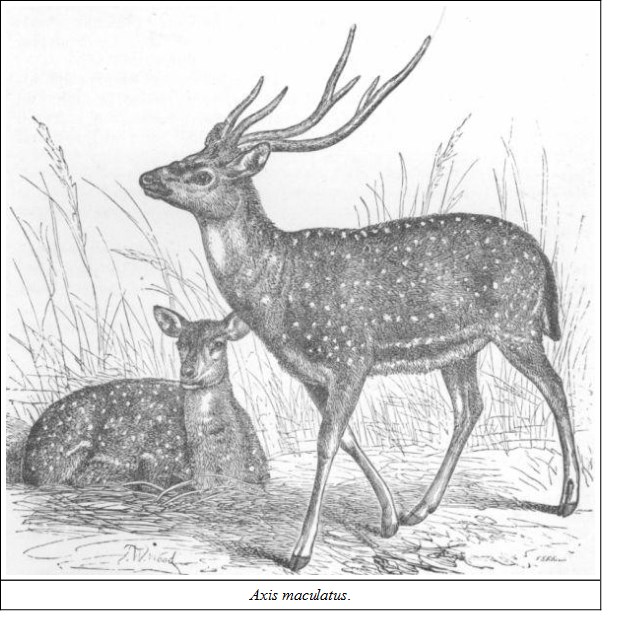

NO. 472. AXIS MACULATUSThe Spotted Deer (Jerdon's No. 221)NATIVE NAMES.—Chital, Chitra, Chritri-jhank (the male), Hindi; Chatidah in Bhagulpore; Boro-khotiya, Bengali at Rungpore; Buriya, in Gorukpore; Saraga, Canarese; Dupi, Telegu; Lupi, Gondi (Jerdon); Tic-mooha, Singhalese (Kellaart); Sarga, Jati, Mikka, Canarese (Sanderson).

HABITAT.—Throughout India, with the exception of the Punjab; nor is it found, I believe, in the countries east of the Bay of Bengal. It is however obtained in Ceylon, where it has been classed by Kellaart as a distinct species, A. oryzeus.

DESCRIPTION.—General colour like that of the English fallow deer, yellowish or rufous fawn, spotted with white; the spots on the sides low down assuming an elongated shape, forming lines; a dark dorsal stripe from nape to tail; head brownish, unspotted; muzzle dark; ears dark externally, white within; chin, throat, and under-parts whitish, as also the inside of limbs and tail; the horns frequently throw out snags on the brow antler.

SIZE.—Length, 4½ to 5 feet. Height at shoulder, 36 to 38 inches. I regret I cannot give accurate measurements just now of horns, as I am writing on board ship, with all my specimens and most of my books boxed up, but I should say 30 inches an average good horn. Jerdon does not give any details.

This deer is generally found in forests bordering streams. I have never found it at any great distance from water; it is gregarious, and is found in herds of thirty and forty in favourable localities. Generally spotted deer and lovely scenery are found together, at all events in Central India. The very name chital recalls to me the loveliest bits of the rivers of the Central provinces, the Nerbudda, the Pench, the Bangunga, and the bright little Hirrie. Where the bamboo bends over the water, and the kouha and saj make sunless glades, there will be found the bonny dappled hides of the fairest of India's deer. There is no more beautiful sight in creation than a chital stag in a sun-flecked dell when—

"Ere his fleet career he tookThe dewdrops from his flanks he shook;Like crested leader, proud and high,Toss'd his beam'd frontlet to the sky;A moment gazed adown the dale,A moment snuff'd the tainted gale,A moment listen'd to the cryThat thicken'd as the chase drew nigh;Then, as the headmost foes appeared,With one brave bound the copse he clear'd."Here I may fitly quote again from "Hawkeye," whose descriptions are charming: "Imagine a forest glade, the graceful bamboo arching overhead, forming a lovely vista, with here and there bright spots and deep shadows—the effect of the sun's rays struggling to penetrate the leafy roof of nature's aisle. Deep in the solitude of the woods see now the dappled herd, and watch the handsome buck as he roams here and there in the midst of his harem, or, browsing amongst the bushes, exhibits his graceful antlers to the lurking foe, who by patient woodcraft has succeeded in approaching his unsuspecting victim; observe how proudly he holds himself, as some other buck of less pretensions dares to approach the ladies of the group; see how he advances, as on tiptoe, all the hair of his body standing on end, and with a thundering rush drives headlong away this bold intruder, and then comes swaggering back! But, hark—a twig has broken! Suddenly the buck wheels round, facing the quarter whence the sound proceeded. Look at him now, and say, is he not a quarry well worth the hunter's notice?

"With head erect, antlers thrown back, his white throat exposed, his tail raised, his whole body gathered together, prepared to bound away into the deep forest in the twinkling of an eye, he stands a splendid specimen of the cervine tribe. We will not kill him; we look and admire! A doe suddenly gives that imperceptible signal to which I have formerly alluded, and the next moment the whole herd has dashed through the bamboo alleys, vanishing from sight—a dappled hide now and again gleaming in the sunlight as its owner scampers away to more distant haunts."

Jerdon is a follower of Hodgson, who was of opinion that there are two species of spotted deer—a larger and smaller, the latter inhabiting Southern India; but there is no reason for adopting this theory; both Blyth, Gray, and others have ignored this, and the most that can be conceded is that the southern animal is a variety owing to climatic conditions. Multiplication of species is a thing to be avoided of all naturalists—I have, therefore, not separated them. McMaster too writes: "I cannot agree with Jerdon that there are two species of spotted deer." And he had experience in Southern India as well as in other parts. He states that the finest chital he ever came across were found in the forests in Goomsoor, where, he adds, "as in every other part of Orissa, both spotted deer and sambar are, I think, more than usually large."

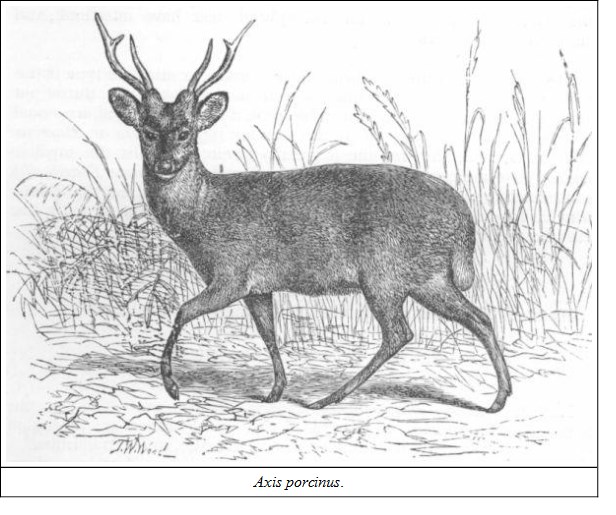

NO. 473. AXIS PORCINUSThe Hog Deer (Jerdon's No. 222)NATIVE NAMES.—Para, Hindi; Jerdon also gives Khar-laguna, Nepal Terai; Sugoria also in some parts. Nuthurini-haran in some parts of Bengal; Weel-mooha, Singhalese (Kellaart).

HABITAT.—Throughout India, though scarce in the central parts; it is abundant in Assam and Burmah, and is also found in Ceylon, but is stated not to occur in Malabar.

DESCRIPTION.—"Light chestnut or olive-brown, with an eye-spot; the margin of the lips, the tail beneath, limbs within, and abdomen, white—in summer many assume a paler and more yellow tint, and get a few white spots, and the old buck assumes a dark slaty colour; the horns resemble those of a young spotted deer, with both the basal and upper tines very small, the former pointing directly upwards at a very acute angle, and the latter directed backwards and inwards, nearly at a right angle, occasionally pointing downwards" (Jerdon). McMaster says: "I can corroborate Jerdon's statement that the young of this deer are beautifully spotted; but, although I have seen many specimens, dead and alive, and still more of the skins while I was in Burmah, I do not remember having remarked the few white spots which he says many of them assume in summer." The fawns lose their spots at about six months.

SIZE.—Length, 42 to 44 inches; tail, 8 inches; height, 27 to 28. Average length of horns, 15 to 16 inches.

This animal is seldom found in forest land; it seems to prefer open grass jungle, lying sheltered during the day in thick patches, and lies close till almost run upon by beaters or elephants. Its gait is awkward, with some resemblance to that of a hog carrying its head low; it is not speedy, and can easily be run down by dogs in the open. McMaster writes: "Great numbers of these deer are each season killed by Burmans, being mobbed with dogs." The meat is fair. Hog deer are not gregarious like chital; they are usually solitary, though found occasionally in pairs.

The horns are shed about April, and the rutting season is September and October. This species and the spotted deer have interbred, and the hybrid progeny survived.

The next stage from the rusine to the cervine or elaphine type is the rucervine. In this the tres-tine, as well as the royal tine, throw out branches, and in the normal rucervine type the tres and royal are equal as in Schomburgk's deer, but in the extreme type, Panolia or Rucervus Eldii of Burmah, the tres-tine is greatly developed, whilst the royal is reduced to a mere snag. The Indian swamp-deer (Rucervus Duvaucelli) is intermediate, both tres and royal tines are developed, but the former is much larger than the royal. In none of the rucervine forms is the bez-tine produced.

GENUS RUCERVUSHorns as above; muzzle pointed. Canines in males only.

NO. 474. RUCERVUS DUVAUCELLIThe Swamp-Deer (Jerdon's No. 219)NATIVE NAMES.—Bara-singha, Hindi; Baraya and Maha in the Nepal Terai; Jhinkar in Kyarda Doon; Potiyaharan at Monghyr (Jerdon); Goen or Goenjak (male), Gaoni (female), in Central India.

HABITAT.—"In the forest lands at the foot of the Himalayas, from the Kyarda Doon to Bhotan. It is very abundant in Assam, inhabiting the islands and churs of the Berhampooter, extending down the river in suitable spots to the eastern Sunderbunds. It is also stated to occur near Monghyr, and thence extends sparingly through the great forest tract of Central India" (Jerdon's 'Mamm. Ind.'). I have found it in abundance in the Raigarh Bichia tracts of Mundla, at one time attached to the Seonee district, but now I think incorporated in the new district of Balaghat. In the open valleys, studded with sal forest, of the Thanwur, Halone, and Bunjar tributaries of the Nerbudda, may be found bits reminding one of English parks, with noble herds of this handsome deer. It seems to love water and open country. McMaster states that it is found in the Golcondah Zemindary near Daraconda.

DESCRIPTION.—Smaller and lighter than the sambar. Colour rich light yellow or chestnut in summer, yellowish-brown in winter, sometimes very light, paler below and inside the limbs, white under the tail. The females are lighter; the young spotted.

SIZE.—Height, about 44 to 46 inches; horns, about 36 inches. They have commonly from twelve to fourteen points, but Jerdon states he has seen them with seventeen.

Like the spotted deer this species is gregarious; one writer, speaking of them in Central India, says: "The plain stretched away in gentle undulations towards the river, distant about a mile, and on it were three large herds of bara singhas feeding at one time; the nearest was not more than five hundred yards away from where I stood. There must have been at least fifty of them—stags, hinds, and fawns, feeding together in a lump, and outside the herd grazed three most enormous stags" ('Indian Sporting Review,' quoted by Jerdon).

NO. 475. RUCERVUS vel PANOLIA ELDIIThe Brown Antlered or Eld's DeerNATIVE NAMES.—Thamin, in Burmah; Sungrai or Sungnaie, in Munipur, Eastern Himalayas, Terai, Munipur, Burmah, Siam, and the Malay peninsula.

DESCRIPTION.—In body similar to the last, but with much difference in the horns, the tres-tine being greatly developed at the expense of the royal, which gives the antlers a forward cast; the brow-tine is also very long. In summer it is a light rufous brown, with a few faint indications of white spots; the under-parts and insides of ears nearly white; the tail short and black above. It is said to become darker in winter instead of lighter as in the last species.

SIZE.—Height from 12 to 13 hands.

This deer, which is identical with Cervus frontalis and Hodgson's Cervus dimorpha, and which was discovered in 1838 by Captain Eld, has been well described by Lieutenant R. C. Beavan. The following extracts have been quoted by Professor Garrod; the full account will be found in the 'Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal.' The food of this species seems to consist of grass and wild paddy. "In habits they are very wary and difficult of approach, especially the males. They are also very timid and easily startled. The males, however, when wounded and brought to bay with dogs, get very savage, and charge vigorously. On being disturbed they invariably make for the open instead of resorting to the heavy jungle, like hog deer and sambar. In fact the thamyn is essentially a plain-loving species; and although it will frequent tolerably open tree-jungle for the sake of its shade, it will never venture into dense and matted underwood. When first started the pace of the thamyn is great. It commences by giving three or four large bounds, like the axis or spotted deer, and afterwards settles down into a long trot, which it will keep up for six or seven miles on end when frequently disturbed."

The next phase of development of which we have examples in India is the true cervine or elaphine type of horn in which the brow-tine is doubled by the addition of the bez; the royal is greatly enlarged at the expense of the tres-tine, and breaks out into the branches known as the sur-royals.

GENUS CERVUSHorns as above, muzzle pointed, muffle large and broad, with a hairy band above the lip; hair coarse, and usually deep brown, with a light and sometimes almost white disc or patch round the tail, which is very short; eye-pits moderate.

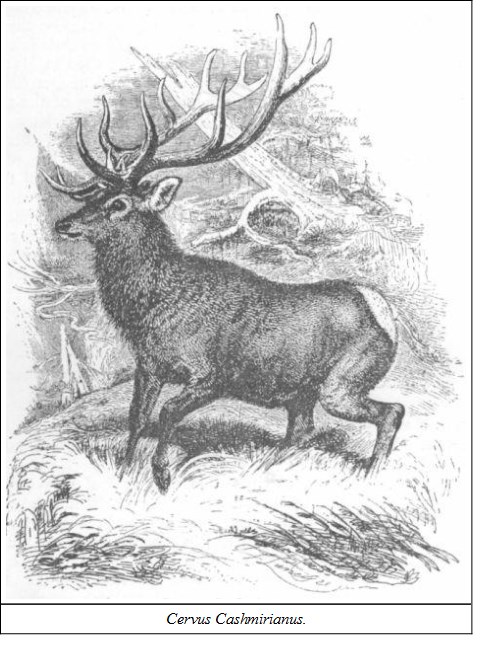

NO. 476. CERVUS CASHMIRIANUSThe Kashmir Stag(Cervus Wallichii of Jerdon, No. 217)NATIVE NAMES.—Hangul or Honglu in Kashmir; Barasingha, Hindi.

HABITAT.—Kashmir. Jerdon also gives out that it is found throughout great part of Western and Central Asia, as far as the eastern shores of the Euxine Sea, and that it is common in Persia, where it is called maral; but according to careful observations made by Sir Victor Brooke the maral is a distinct species, to which I will allude further on. In Kashmir it frequents the Sind valley and its offshoots; the country above also.

DESCRIPTION.—Brownish-ash, darker along the dorsal line; caudal disk white, with a dark border; sides and limbs paler; ears light coloured; lips and chin and a circle round eyes white. The male has very long and shaggy hair on the lower part of the neck. The colour of the coat varies but little; at times it is liver-coloured or liver-brown, sometimes "bright pale rufous chestnut," with reddish patches on the inner sides of the hips. Jerdon says: "The belly of the male is dark brown, contrasting with the pale ashy hue of the lower part of the flanks; the legs have a pale dusky median line. In females the whole lower parts are albescent."

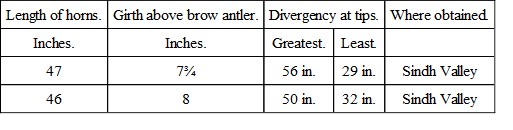

SIZE.—Length, 7 to 7½ feet; height, 12 to 13 hands; tail, 5 inches. The horns are very large and massive, with from ten to fifteen, or even more, points. Jerdon states that even eighteen points have been counted, but such cases are rare. Dr. Leith Adams says the largest he ever measured were four feet round the curves. "A. E. W." in his interesting papers on Kashmir game, published in The Asian, gives the following measurements of two heads:—

I once saw a beautiful head at a railway-station, the property of an officer who had just come down from Kashmir, the horns of which appeared to me enormous. The owner afterwards travelled with me in the train, and gave me his card, which I regret I lost, and, having forgotten his name, I was never enabled to write to him, either on the subject of the horns or to send him some papers he wanted on Asiatic sheep.

Dr. Leith Adams writes: "They (the horns) are shed in March, and the new horn is not completely formed till the end of October, when the rutting season commences, and the loud bellowings of the stags are heard all over the mountains." Of this bellowing Sir Victor Brooke says it is just like the voice of the Wapiti stag, which this animal closely resembles, and is quite different from that of the red deer. "In the former it is a loud squeal, ending in a more gutteral tone; in the latter it is a distinct roar, resembling that of a panther." Sir Victor Brooke also points out another peculiarity in this deer: namely, that "the second brow antler (bez) in Cervus Cashmirianus, with very rare exceptions, exceeds the brow antler in length; a peculiarity by which the antlers of this species may be distinguished from those of its allies."

The female gives birth in April, and the young are spotted.

The points on which this stag differs from the maral are the longer and more pointed head of the latter.

NO. 477. CERVUS AFFINIS vel WALLICHIIThe Sikhim Stag (Jerdon's No. 218)NATIVE NAME.—Shou, Thibetan.

HABITAT.—Eastern Himalayas; Thibet in the Choombi valley, on the Sikhim side of Thibet.

DESCRIPTION.—Jerdon describes this stag as "of very large size; horns bifurcated at the tip in all specimens yet seen; horns pale, smooth, rounded, colour a fine clear grey in winter, with a moderately large disk; pale rufous in summer." Hodgson writes of the horns: "Pedicles elevate; burrs rather small; two basal antlers, nearly straight, so forward in direction as to overshadow the face to the end of the nasal; larger than the royal antlers; median or royal antlers directed forward and upwards; beam with a terminal fork, the prongs radiating laterally and equally, the inner one longest and thinnest." Jerdon adds: "Compared with the Kashmir stag this one has the beam still more bent at the origin of the median tine, and thus more removed from C. elaphus, and like C. Wallichii (C. Cashmirianus)." The second basal tine or bez antler is generally present, even in the second pair of horns assumed. Moreover the simple bifurcation of the crown mentioned above is a still more characteristic point of difference both from the Kashmir barasingha and the stag of Europe.

Regarding the nomenclature of this species there seems to be some uncertainty. Jerdon himself was doubtful whether the shou was not C. Wallichii, and the Kashmir stag C. Cashmirianus. He says: "It is a point reserved for future travellers and sportsmen to ascertain the limits of C. Wallichii east and C. affinis west, for, as Dr. Sclater remarks, it would be contrary to all analogy to find two species of the same type inhabiting one district."

Sir Victor Brooke writes: "Should Cervus Wallichii (Cuvier) prove to be specifically identical with Cervus affinis (Hodgson), the former name, having priority, must stand."

SIZE.—Length, about 8 feet; height at shoulders, 4½ to 5 feet. Horns quoted by Jerdon 54 inches round curve, 47 inches in divergence between the two outer snags. Longest basal tine, 12 inches; the medians, 8 inches.

An allied stag, Cervus maral, is found in Circassia and Persia. Sir Victor Brooke mentions a pair kept for some years in one of his parks, which never interbred with the red deer, and kept apart from them. "The old stag maral, though considerably larger in size, lived in great fear of the red deer stag." Another very fine species, Cervus Eustephanus, was discovered by Mr. W. Blanford inhabiting the Thian Shan mountains. As yet it is only known from its antlers, which are of great size, and in their flattened crowns closely resemble Wapiti horns.

TRAGULIDÆ—THE CHEVROTIANS OR DEERLETSAnimals of small size and delicate graceful form, which are separated from the deer and oxen by certain peculiarities which approximate them to the swine in their feet. They are, however, ruminants, having the complex stomach, composed of paunch, honeycomb-bag and reed, the manyplies being almost rudimentary; but in the true ruminants the two centre metacarpals are fused into a single bone, whilst the outer ones are rudimentary. In the pig all the metacarpal bones are distinct, and the African Tragulus closely resembles it. The Asiatic ones have the two centre bones fused, but the inner and outer ones are entire and distinct as in the swine. The legs are, however, remarkably delicate, and so slight as to be not much thicker than an ordinary lead pencil. The males have pendant tusks, like those of the musk and rib-faced deer.

GENUS TRAGULUSHas the hinder part of metatarsus bald and callous.

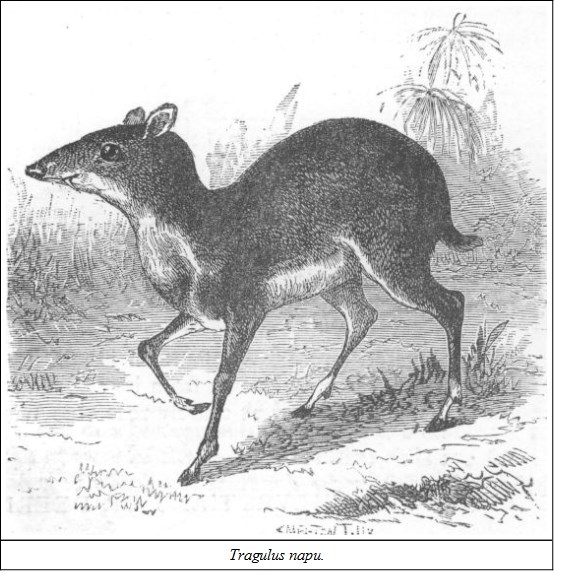

NO. 478. TRAGULUS NAPUThe Javan DeerletNATIVE NAME.—Napu.

HABITAT.—Tenasserim and the Malay countries.

DESCRIPTION.—Above rusty brown, with three whitish stripes; under-parts white, tail tipped with white, muzzle black.

Tragulus kauchil is another Malayan species yet smaller than the preceding; it may be found in Tenasserim. It is darker in colour than the last, especially along the back, with a broad black band across the chest.

GENUS MEMINNAHinder edge of metatarsus covered with hair.

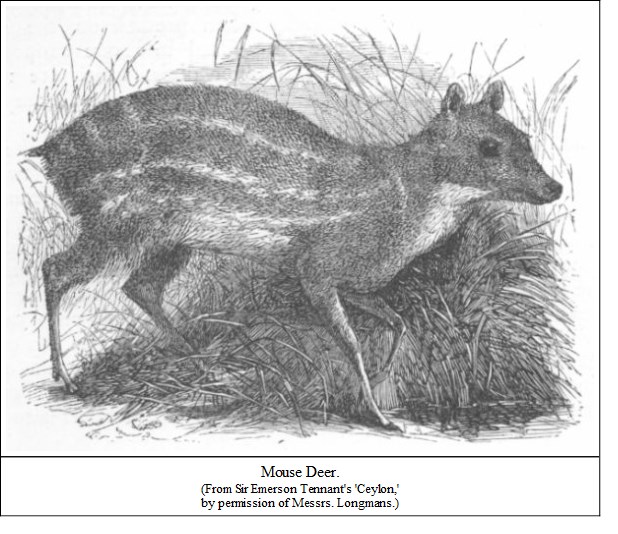

NO. 479. MEMINNA INDICAIndian Mouse DeerNATIVE NAMES.—Pisuri, Pisora, Pisai, Hindi and Mahratti; Mugi in Central India; Turi-maoo, Gondi; Jitri-haran, Bengali; Gandwa, Ooria; Yar of the Koles; Wal-mooha, Singhalese.

HABITAT.—In all the large forests of India; but is not known, according to Jerdon, in the countries eastward of the Bay of Bengal. It is common in the bamboo forests of the Central provinces, where I obtained it on several occasions.

DESCRIPTION.—"Above olivaceous, mixed with yellow grey; white below; sides of the body with yellowish-white lines formed of interrupted spots, the upper rows of which are joined to those of the opposite side by some transverse spots; ears reddish-brown" (Jerdon). The colour however varies; some are darker than others.

SIZE.—Length, 22 to 23 inches; tail, 1½ inches; height, 10 to 12 inches. Weight, 5 to 6 lbs.

The above measurements and weight are taken from Jerdon. Professor Garrod (Cassell's Nat. His.) gives eighteen inches for length and eight inches for height, which is nearer the size of those I have kept in confinement; but mine were young animals. They are timid and delicate, but become very tame, and I have had them running loose about the house. They trip about most daintily on the tips of their toes, and look as if a puff of wind would blow them away.

They are said to rut in June and July, and bring forth two young about the end of the rainy season.

TRIBE TYLOPODA—THE CAMELSThis name, which is derived from the Greek [Greek: túlos], a swelling, pad, or knot, and [Greek: poús], a foot, is applied to the camels and llamas, whose feet are composed of toes protected by cushion-like soles, and not by a horny covering like those of the Artiodactyli generally. The foot of the camel consists of two toes tipped by small nails, and protected by soft pads which spread out laterally when pressed on the ground. The two centre metacarpal bones are fused into one cannon bone, and the phalanges of the outer and inner digits which are more or less traceable in all the other families of the Artiodactyli are entirely absent.

The dentition of the camel too is somewhat different from the rest of the Ruminantia, for in the front of the upper jaw there are two teeth placed laterally, one on each side, whereas in all other ruminating animals there are no cutting teeth in the upper jaw—only a hard pad, on which the lower teeth are pressed in the act of tearing off herbage.

The stomach of the camel is the third peculiarity which distinguishes it. The psalterium or manyplies is wanting. The abomasum or "reed" is of great length, and the rumen or paunch is lined with cells, deep and narrow, like those of a honeycomb, closed by a membrane, the orifice of which is at the control of the animal. These cells are for the purpose of storing water, of which the stomach when fully distended will hold about six quarts. The second stomach or reticulum is also deeply grooved.

The hump of the camel may also be said to contain a store of food. It consists of fatty cells connected by bands of fibrous tissue, which are absorbed, like the fat of hibernating bears, into the system in times of deprivation. Hard work and bad feeding will soon bring down a camel's hump; and the Arab of the desert is said to pay particular attention to this part of his animal's body.