полная версия

полная версияNatural History of the Mammalia of India and Ceylon

"The colour of the adult in one stage is fulvous throughout, some of the hairs being dark tipped. Legs, tail, muzzle and dorsal stripe black.

"Old bulls appear to become of an uniform brownish-black at times, but the colour doubtless depends on the season, as each hair has the basal two-thirds yellow, and its apical third black, and the young its hair brown with a dark tint. The takin, pronounced takhon (nasally), is found just outside British limits in the Mishmi and Akha hills, north of Assam. It extends into the mountainous parts of Chinese Thibet, whence it has lately been procured by the adventurous Abbé David, and has been described by the great French naturalist A. Milne-Edwards, in his work 'Recherches sur les Mammifères,' with some osteological details which were hitherto wanting, but no more than the limb bones appear to have been obtained.

"The horns of the takin have been considered to bear some likeness to those of the gnu (Catoblepas), but I fail to trace a resemblance. Hodgson's description of the horns is as follows:—

"'The horns of the takin are inserted on the highest part of the forehead. The horns are nearly in contact at their bases. Their direction is first vertically upwards, then horizontally outwards, or to the sides, and then almost as horizontally backwards. The length of each horn is about 20 inches along the curves, but their thickness is great. The tail is about three inches long.'

"This remarkable animal was originally described by Brian Hodgson in 1850, from specimens procured by Major Jenkins from the Mishmis, north-east of Sadya. Skulls and skins are fairly common among the residents of Debroogurh, and two perfect skins of adults were lately presented by Colonel Graham to the Indian Museum.

"It is to be regretted that the skeleton of the animal remains unknown to science; from information collected by myself from the Mishmis, it was apparent that they might easily be procured.

"The animal would appear to range from about 8000 feet to the Alpine region, which is stated to be its habitat.

"While at Sadya a Mishmi chief pointed me out various spurs of the Himalayas, tantalisingly close, where he stated that he had hunted the animal.

"Hodgson's paper on the takin was published in the 'Jour. As. Soc.' vol. xix., pp. 65, 75, with three plates, a drawing of the animal, and two views of the skull.

"The next figure was by Wolf, in the 'Proc. of the Zool. Soc.' for 1853, pt. xxxvi., and is perhaps the worst he has ever done. Neither of these drawings are correct; and it is to be hoped that Professor Milne-Edwards has more materials for his picture than flat skins and limb bones.

"Professor Milne-Edwards was inclined to consider his specimens a distinct variety from the Mishmi animal, and calls it Budorcas taxicola (sic) var. Tibetana.

"The difference the professor points out, namely the fulvous colour and the thinner undeveloped horns, exist in various specimens of the Mishmi takin, and there can be no question but that the animals are identical.

"The slaty colour of Wolf's drawing is probably due to an incorrect conception of Hodgson's term grey, which he defines as a yellowish-grey.

"The takin is essentially a serow (Nemorhoedus), with affinities to the bovines through the musk ox (Ovibos moschata), and other relationship to the sheep, goat and antelope. The development of the spurious hoofs would indicate that it frequents very steep ground."—J. C.

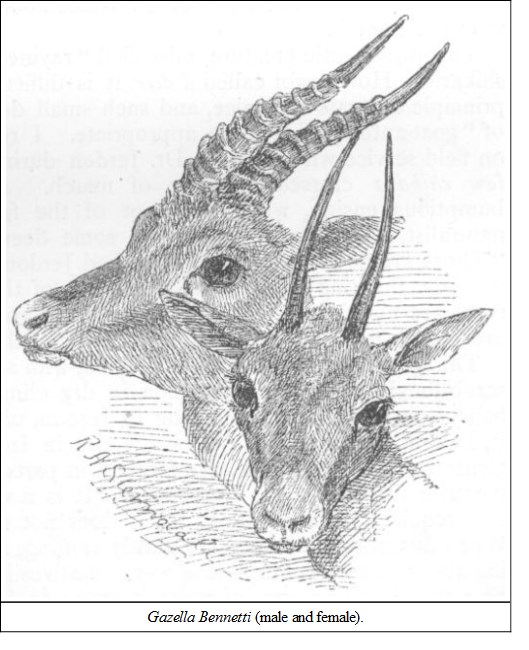

GENUS GAZELLA—THE GAZELLESThese are small animals of slender frame; bovine muzzle; of sandy colour above and white underneath; small annulated horns, curved gracefully backwards, and in some species so elegantly formed as to take the shape of a lyre on looking at them full in front. The females of some have smaller, smoother horns, but others are hornless. The skull has an anteorbital vacuity, with a small anteorbital fossa. The auditory bullæ are large; "eye-pits small; groin-pits distinct; large feet-pits in all feet; knees tufted" (Jerdon). The face has a white band running from the outer side of the base of each horn down to the muzzle, the space between forming a dark triangular patch bordered with a deeper tint. Sir Victor Brooke classifies the twenty or so known species as follows:—

I.—BACK UNSTRIPEDDentition:—Inc. 0/3; can. 0/1; prem. 3/3; molars, 3/3A.—The white colour of the rump not encroaching on the fawn of the haunches.

a. BOTH SEXES WITH HORNSHorns lyrate or semi-lyrate: Gazella dorcas; G. Isabella; G. rufifrons; G. loevipes; G. melanura.

Horns non-lyrate: Gazella Cuvieri; G. leptoceros; G. Spekii; G. Arabica; G. Bennetti; G. fuscifrons.

b. FEMALES HORNLESSGazella subgutterosa; G. gutterosa; G. picticaudataB.—White of rump projecting forwards in an angle into the fawn colour of the haunches.

Gazella dama; G. mohr; G. Soemmerringii; G. GrantiII.—BACK WITH A WHITE MEDIAN STRIPEOne premolar less in the lower jaw: Gazella euchoreOf the above species the following come under the scope of this work: Gazella Bennetti; G. fuscifrons; G. subgutterosa; G. picticaudata.

NO. 456. GAZELLA BENNETTIThe Indian Gazelle (Jerdon's No. 229)NATIVE NAMES.—Chikara, Hindi; Kal-punch, Hindi; Kal-sipi, Mahratti; Hirni, in the Punjab; Tiska, also Budari and Mudari, Canarese; Barudu-jinka, Telegu; Porsya (male) and Chari (female), of Baoris.

HABITAT.—Mr. W. Blanford defines the limits of this species as follows ('P. Z. S.,' 1873, p. 315)—the italics are mine: "It is found throughout the Punjab, North-west Provinces, Rajputana, Sind (unless in part replaced by the next species), Kachh, Kathiawar, Guzerat, and the whole Bombay Presidency, with the exception of the Western Ghâts and the low land on Konkan, along the western coast, south of the neighbourhood of Daman. It is also met with in the Narbada and Tapti valleys, Bandelkand, the Son valley, and Rewah, in the Nagpur and Chanda country, Berar, the Hyderabad territories, and other parts of Southern India, with the complete exception of the Malabar coast and the adjacent hills." He adds that from the evidence of Colonel McMaster and Colonel Douglas Hamilton, both good authorities, it is not known to occur much south of the Krishna river, nor is it found in the Ganges valley east of Benares, in Eastern Behar, the Santal Pergunnahs, Chotia Nagpur, Birbhum, &c., Chhatisgurh, the Mahanadi valley, Orissa, Bastar, and the east coast, generally north of the river Krishna. He says it is met with in the Narbada valley, but I have also found it common on the plateaux of the Satpura range.

DESCRIPTION.—"Fawn brown above, darker where it joins the white of the sides and buttocks; chin, breast, lower parts and buttocks behind white; tail, knee-tufts and fetlocks behind black; a dark brown spot on the nose, and a dark line from the eyes to the mouth, bordered by a light one above" (Jerdon).

SIZE.—Length, 3½ feet; height, 26 inches at shoulder, 28 inches at croup.

The horns run from 10 to 14 inches in the male, but, in fact, few exceed a foot. The longest of six pairs in my collection measure 12 inches, and the head is looked upon as a fine one. I agree with Jerdon that there must be some mistake about 18-inch horns recorded from the Punjab.

This pretty little creature, miscalled "ravine-deer," is familiar to most shikaris. How it got called a deer it is difficult to say, except on the principle of "rats and mice, and such small deer." The Madras term of "goat-antelope" is more appropriate. I remember once, when out on field service with the late Dr. Jerdon during the Indian Mutiny, a few chikara crossed our line of march. A young and somewhat bumptious ensign, who knew not of the fame of the doctor as a naturalist, called out: "There are some deer, there are some deer." "Those are not deer," quietly remarked Jerdon. "Oh, I say," exclaimed the boy, thinking he had got a rise out of the doctor; "Jerdon says those are not deer!" "No more they are, young man—no more they are; much more of the goat—much more of the goat."

This gazelle frequents broken ground, with sandy nullahs bordered by scrub jungle, and is most common in dry climates. It is unknown, I believe, in Bengal and, according to Jerdon, on the Malabar coast, but is, I think, found almost everywhere else in India. It abounds in the Central provinces, and I have found it in parts of the Punjab, and it is common throughout the North-west. It is a wary, restless little beast, and requires good shooting, for it does not afford much of a mark. When disturbed they keep constantly shifting, not going far, but hovering about in a most tantalising way. Natives it cares little for, unless it be a shikari with a gun, of which it seems to have intuitive perception; but the ordinary cultivator, with his load of wood and grass, may approach within easy shot; therefore it is not a bad plan, when there is no available cover, to get one of these men to walk alongside of you, whilst, with a horse-cloth or blanket over you, you make yourself look as like your guide as you can. A horse or bullock is also a great help. I had a little bullock which formed part of some loot at Banda—a very handsome little bull, easy to ride and steady under fire—and I found him most useful in stalking black buck and gazelle.

When alarmed, the chikara stamps its foot and gives a sharp little hiss. It is generally found in small herds of four or five, but often singly. Jerdon, however, says that in the extreme North-west he had seen twenty or more together, and this is corroborated by Kinloch.

They are sometimes hunted by hawks and dogs combined, the churrug (Falco sacer) being the hawk usually employed, as mentioned both by Kinloch and Hodgson, writing of opposite ends of the great Himalayan chain. The hawk stoops at the head of its quarry and confuses it, whilst the dogs, who would otherwise have no chance, run up and seize it.

The poor little gazelle has also many other enemies—jackals and wolves being amongst the number. Captain Baldwin, in his interesting book, writes: "Like other antelopes, the little ravine-deer has many enemies besides man. One day, when out with my rifle, I noticed an old female gazelle stamping her feet, and every now and then making that hiss which is the alarm note of the animal. It was not I that was the cause of her terror, for I had passed close to her only a few minutes before, and she seemed to understand by my manner that I meant no harm; no, there was something else. I turned back, and, on looking down a ravine close by, saw a crafty wolf attempting a stalk on the mother and young one. Another day, at Agra, a pair of jackals joined in the chase of a wounded buck." Brigadier-General McMaster also relates how he and two friends, whilst coursing, watched for a long time four jackals trying to force one of a small herd of young bucks to separate from the rest. "The gazelles stood in a circle, and maintained their ground well by keeping their heads very gallantly outwards to their foes, until at length, seeing us, both sides made off. We laid the greyhounds into and killed one of the jackals."

NO. 457. GAZELLA FUSCIFRONSThe Baluchistan GazelleHABITAT.—The deserts of Jalk between Seistan and Baluchistan.

DESCRIPTION.—"Central facial band strongly marked, grizzled black; light facial streak grey, fairly definite, as is also the blackish dark facial streak; cheeks and anterior of neck grey; back of the neck, back, sides, haunches and legs sandy; lateral streaks wanting; belly and rump whitish; knee-brushes long, black; ears very long; horns (of female only known) strongly annulated, bending forwards and very slightly inwards at the tips" (Sir V. Brooke, 'P. Z. S.,' 1873, p. 545).

SIZE.—Total length, from tip of nose to end of tail, 4 feet; height at shoulder, 1 foot 11 inches.

This curious species was first brought to notice by Mr. Blanford. It is distinguished, he says, from the Indian G. Bennetti—first by colour, and secondly by the greater length and more strongly marked annulation of the horns of the female. "The face in the Indian gazelle," he says, "is nearly uniform rufescent fawn colour; the parts that are black and blackish in G. fuscifrons being only a little darker than the rest in G. Bennetti; the back also in the latter is more rufescent and less yellow, and the hairs are less dense."

The following two species belong to section B, of which the females are hornless.

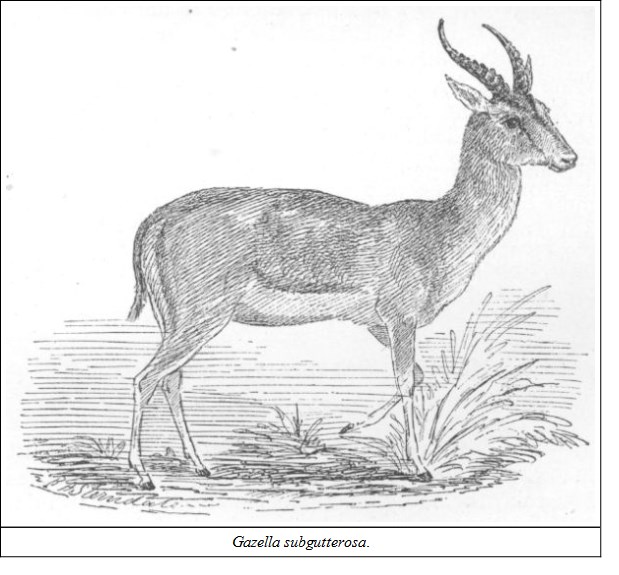

NO. 458. GAZELLA SUBGUTTEROSAThe Persian GazelleNATIVE NAMES.—Kik, Sai-kik, and Jairan, Turki of Yarkand and Kashgar (Blanford).

HABITAT.—The high lands of Persia; to the north-west it is found as far as Tabriz; it is probably, according to Blanford, the gazelle of Meshed and Herat; on the east it extends to the frontier of India, and is found in Afghanistan and northern Baluchistan; a variety also exists in Yarkand.

DESCRIPTION.—"Hair in winter rough and coarse, in summer much softer and smoother. During both seasons the dirty white of the face and cheeks is only relieved by the dark facial streak, which is short and narrow, but defined by a sprinkling of rufous hairs; the lateral and pygal bands are very faintly indicated, the dark bands being more rufous, the light band rather paler than the grey fawn colour of the upper parts of the body; breast and belly white; tail and ears moderate in length, the former blackish-rufous. Horns absent in the female; in the male long, annulated and lyrate, the points projecting inwards" (Sir V. Brooke). According to Blanford, who seemed doubtful whether it should not be raised to the rank of a species, the Yarkand variety differs from the typical G. subgutterosa in the very much darker markings on the face, and in the much smaller degree to which the horns diverge; he adds, however, that as there is some variation in face-markings amongst Persian specimens, it is perhaps better to consider the Yarkand race as only a variety. He gives a very good coloured plate of the animal. ('Sc. Results, Second Yarkand Mission—Mammalia.')

NO. 459. GAZELLA PICTICAUDATAThibetan GazelleNATIVE NAME.—Goa, Thibetan.

HABITAT.—Ladakh. Abundant, according to Kinloch, on the plateau to the south-east of the Tsomoriri lake, on the hills east of Hanlé, and in the Indus valley from Demchok, the frontier village of Ladakh, as far down as Nyima. He had also seen it on the Nakpogoding pass to the north of the Tsomoriri, and picked up a horn on the banks of the Sutlej beyond the Niti pass.

DESCRIPTION.—Hair in winter long and softish; facial and lateral markings wanting; breast, belly and anal disk which surrounds the tail dirty white; the rest of the body grizzled fawn-colour, becoming more rusty towards the anal disk, a rusty line sometimes running through the disk to the short tail, the tip of which is rusty brown; the hairs about the corners of the mouth elongated. In the summer the coat is short and of a slaty-grey colour. Ears very short; horns long, annulated—diverge as they rise, bending forwards and backwards, again forwards, and a little inwards at the tips. Skull: anteorbital fossa very shallow, nasals converging to a point, and rather elongated (Sir Victor Brooke, 'P. Z. S.,' 1873, p. 547).

SIZE.—Height, about 18 inches.

There is a lovely little photograph of this gazelle in Kinloch's 'Large Game of Thibet,' wonderfully life-like; the head seems to stand out from the page. He describes it under Hodgson's generic name, Procapra, but there is no reason for separating it from Gazella. He says: "The goa avoid rocky and steep ground, preferring the undulating plains and gently sloping valleys. Early in the season they are to be found in small herds, frequently close to the snow; as this melts they appear to disperse themselves over the higher ground, being often found singly or in twos and threes."

GENUS PANTHOLOPS

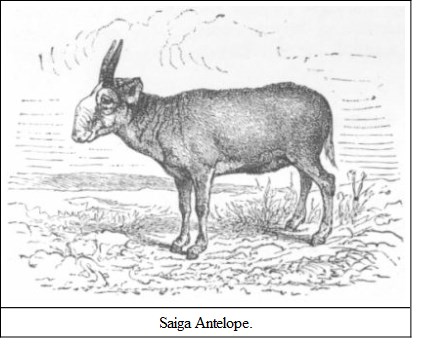

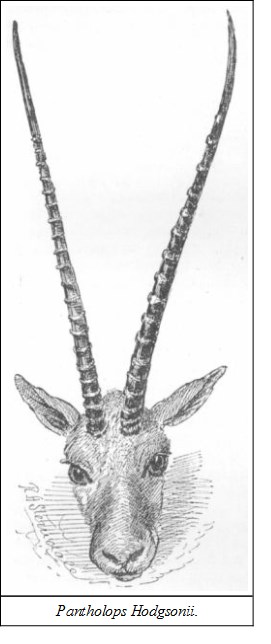

Between the gazelles and antelopes proper comes the chiru (Pantholops Hodgsonii), though strictly speaking it is, with the saiga antelope (Saiga Tartarica), though in a somewhat less degree, connected by cranial affinities with the sheep. The saiga is notable for its highly-arched nose and inflated nostrils, which are so much lengthened as to necessitate the animal's walking backwards when it feeds. The chiru is not quite so developed in this respect. The skull of the saiga is unique among ruminants, and those who wish to become acquainted with its most minute osteological details should refer to an article on this animal by Dr. James Murie in the 'P. Z. S.,' 1870, p. 457. I can only here give a very brief summary of the chief characteristics. Looked at in profile, the nasal bones we find to be remarkably short, the face being hollowed out, as it were, between the upper nasal cartilage and the very long and narrow maxillary and pre-maxillary bones; great vertical depth from the top of the nasal to the bottom of the maxillary bones; a very prominent bovine orbit, above and a little behind which the short tapering horns of a gazelle type are placed. The lower nasal cartilage is prolonged on to the fibrous cord of the nares, and the profile view of the animal in life is that of a grotesquely Roman-nosed antelope with swollen nostrils. Its nearest relative in India is the chiru, which has certain points of resemblance. The nose is but slightly arched, but the nostrils are more swollen than in antelopes as a rule. This is not sufficiently rendered in an otherwise admirable coloured plate in Blanford's 'Scientific Results of the Second Yarkand Mission,' but it is more apparent in the photograph of the head in Kinloch's 'Large Game of Thibet.' Another approach to the saiga is in the position of the horns, which, though of the same class, are much longer and more attenuated, but the position over the eye and the osseous development of the orbit are the same. The nasal bones are also shorter in proportion to other antelopes. The super-orbital foramina just under the horns, which are marked in most antelope and deer, are very minute in Pantholops. Dr. Murie notices the inflation of the post-maxilla in the saiga, and states that a similar extension is to be found in the chiru.

NO. 460. PANTHOLOPS HODGSONIIThe ChiruNATIVE NAMES.—Chiru in Nepal; Isos in Thibet (Strachey); also Isors or Choos (Kinloch).

HABITAT.—The open plains of Thibet from Lhassa to Ladakh.

DESCRIPTION.—The following description was written in 1830, apparently by Mr. Brian Hodgson himself, and was published in 'Gleanings in Science' (vol. ii., p. 348), probably the first scientific magazine in India. As I have seen no better account of this curious antelope I give it as it stands. Mr. Hodgson had the advantage of drawing from life, he having had a living specimen as a pet:—

"Antelope with very long, compressed, tapering, sub-erect (? sub-lyrated) horns, having a slight concave arctuation forwards, and blunt annulations (prominently ridged on the frontal surface), except near the tips; a double coat throughout, greyish blue internally, but superficially fawn-coloured above, and white below, a black forehead, and stripes down the legs; and a tumour or tuft above either nostril.

"The ears and tail are moderate and devoid of any peculiarity; so likewise are the sub-orbital sinuses.38 The horns are exceedingly long, measuring in some individuals nearly 2½ feet. They are placed very forward on the head, and may popularly be said to be erect and straight, though a reference to the specific character will show that they are not strictly one or the other.

"The general surface of the horns is smooth and polished, but its uniformity is broken by a series of from fifteen to twenty rings extending from the base to within six inches of the tip of each horn. Upon the lateral and dorsal surfaces of the horns these rings are little elevated, and present a wavy rather than a ridgy appearance; but on the frontal surface the rings exhibit a succession of heavy, large ridges, with furrows between; the annulation is nowhere acutely edged. The horns have a very considerable lateral compression towards the base, where their extent fore and aft is nearly double of that from side to side; upwards from the base the lateral compression becomes gradually less, and towards their tips the horns are nearly rounded. Compared with their length the thickness of the horns is as nothing—in other words they are slender, but not therefore by any means weak. The tips are acute rather than otherwise; the divergence at the points is from one-third to one-half of the length. At the base a finger can hardly be passed between the horns. Throughout five-sixths of their length from the base the horns describe an uniform slightly inward curve, and on the top angle of the curve they turn inwards again more suddenly, but still slightly, the points of the horns being thus directed inwards; the lateral view of the horns shows a considerable concave arctuation forwards, but chiefly derived from the upper part of the horns."

There is an excellent coloured plate of this animal in Blanford's 'Mammalia of the Second Yarkand Mission.' The only fault I see lies in the muzzle, especially of the male, which the artist has made as fine as that of a gazelle. The photograph in Kinloch's 'Large Game of Thibet' shows the puffiness of the nostrils much better; the latter author says of it:—

"The Thibetan antelope is a thoroughly game-looking animal; in size it considerably exceeds the common black buck or antelope of India, and is not so elegantly made. Its colour is a reddish fawn, verging on white in very old individuals. A dark stripe runs down the shoulders and flanks, and the legs are also dark brown. The face alone is nearly black, especially in old bucks. The hair is long and brittle, and extraordinarily thick-set, forming a beautiful velvety cushion, which must most effectually protect the animal from the intense cold of the elevated regions which it inhabits. A peculiarity about this antelope is the existence of two orifices in the groin, which communicate with long tubes running up into the body. The Tartars say that the antelope inflates these with air, and is thereby enabled to run with greater swiftness! The muzzle of the Thibetan antelope is quite different from that of most of the deer and antelope tribe, being thick and puffed looking, with a small rudimentary beard; the eyes are set high up in the head; the sub-orbital sinus is wanting; the horns are singularly handsome, jet black, and of the closest grain, averaging about twenty-three or twenty-four inches in length. They are beautifully adapted for knife handles. The females have short black horns, and are much smaller than the males."

The last is a doubtful point; as far as I have been able to gather evidence on the subject the female appears to be hornless, which allies Pantholops more to the antelopes and the gazelles. Major Kinloch may have taken some young males for females, the general colouring being much the same. In the 'Proceedings of the Zoological Society' for 1834, p. 80, there is an extract from a letter from Mr. Hodgson, which, with reference to previous correspondence, says: "The communications referred to left only the inguinal pores, the number of teats in the female, and the fact of her being cornute or otherwise, doubtful. These points are now cleared up. The female is hornless, and has two teats only; she has no marks on the face or limbs, and is rather smaller than the male. The male has a large pouch at each groin, as in Ant. dorcas; that of the female is considerably smaller." Mr. Hodgson further remarks that "the chiru antelope can only belong either to the gazelline or the antelopine group. Hornless females would place it among the latter; but lyrate horns, ovine nose, and want of sinus, would give it rather to Gazella, and its singular inguinal purses further ally it to Ant. dorcas of this group. But from Gazella it is distinguished by the accessory nostrils, of inter-maxillary pouch, the hornless females, the absence of tufts on the knees, and of bands on the flanks. The chiru, with his bluff bristly nose, his inter-maxillary pouches, and hollow-cored horns, stands in some respects alone."