полная версия

полная версияNatural History of the Mammalia of India and Ceylon

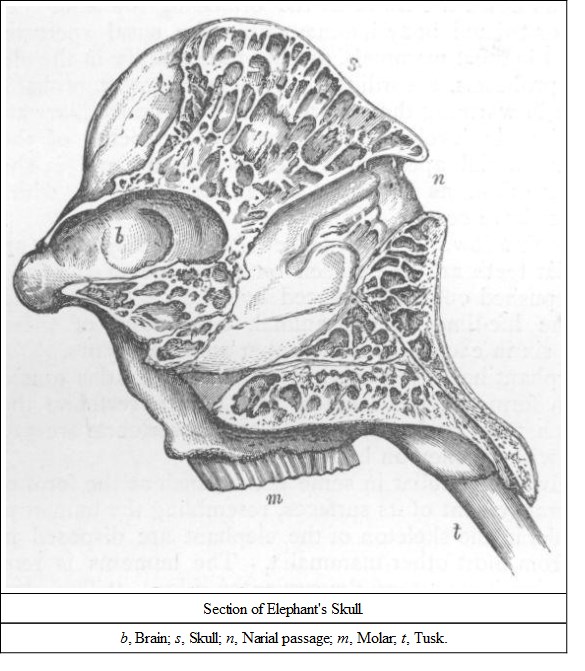

There are no lower incisors (except in a fossil species), and only two of the molar teeth are to be seen on each side of the jaw at a time, which are pushed out and replaced by others which grow from behind. During the life-time of the animal, twenty-four of these teeth are produced, six in each side of the upper and lower jaws.

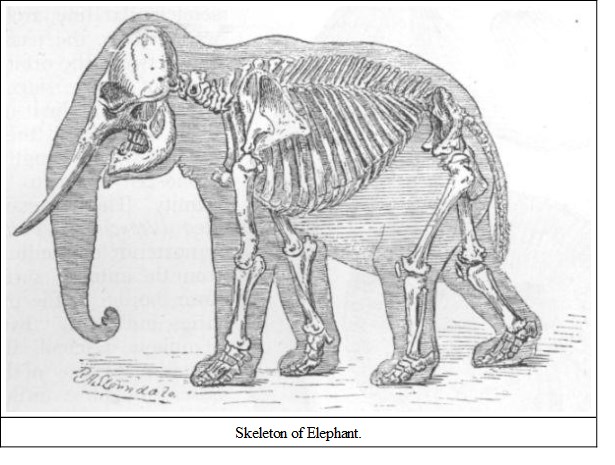

The elephant has seven cervical vertebræ, the atlas much resembling the human form; of the thoracic and lumbar vertebræ the number is 23, of which 19 or 20 bear ribs; the caudal vertebræ are 31, of a simple character, without chevron bones.

The pelvis is peculiar in some points, such as the form of the ileum and the arrangement of its surfaces, resembling the human pelvis.

The limbs in the skeleton of the elephant are disposed in a manner differing from most other mammalia. The humerus is remarkable for the great development of the supinator ridge. "The ulna and radius are quite distinct and permanently crossed; the upper end of the latter is small, while the ulna not only contributes the principal part of the articular surface for the humerus, but has its lower end actually larger than that of the radius—a condition almost unique among mammals" (Prof. Flower).

On looking at the skeleton of the elephant, one of the first things that strikes the student of comparative anatomy is the perpendicular column of the limbs; in all other animals the bones composing these supports are set at certain angles, by which a direct shock in the action of galloping and leaping is avoided. Take the skeleton of a horse, and you will observe that the scapula and humerus are set almost at right angles to each other. It is so in most other animals, but in the elephant, which requires great solidity and columnar strength, it not being given to bounding about, and having enormous bulk to be supported, the scapula, humerus, ulna and radius are all almost in a perpendicular line. Owing to this rigid formation, the elephant cannot spring. No greater hoax was ever perpetrated on the public than that in one of our illustrated papers, which gave a picture of an elephant hurdle-race. Mr. Sanderson, in his most interesting book, says: "He is physically incapable of making the smallest spring, either in vertical height or horizontal distance. Thus a trench seven feet wide is impassable to an elephant, though the step of a large one in full stride is about six and a half feet."

The hind-limbs are also peculiarly formed, and bear some resemblance to the arrangement of the human bones, and in these the same perpendicular disposition is to be observed; the pelvis is set nearly vertically to the vertebral column, and the femur and tibia are in an almost direct line. The fibula, or small bone of the leg, which is subject to great variation amongst animals (it being merely rudimentary in the horse, for instance), is distinct in the elephant, and is considerably enlarged at the lower end. The tarsal bones are short, and the digits have the usual number of phalanges, the ungual or nail-bearing ones being small and rounded.

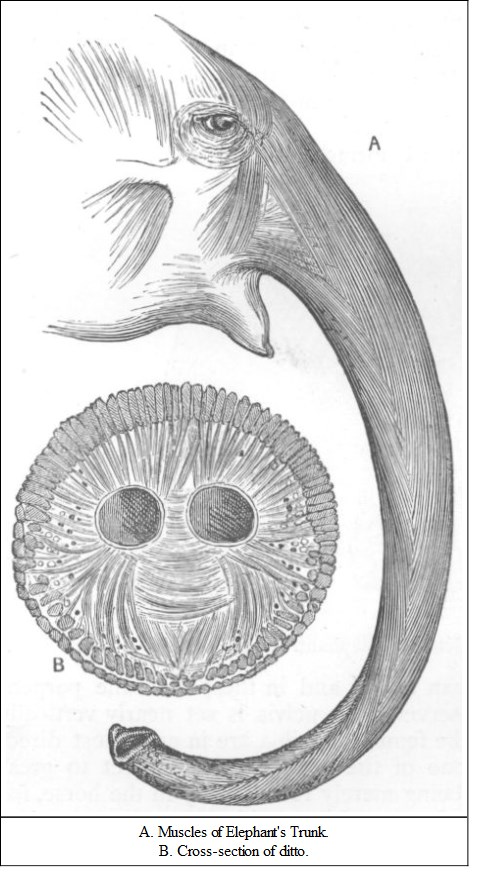

I have thus briefly summarised the osteology of the elephant, as I think the salient points on which I have touched would interest the general reader; but, in now proceeding to the internal anatomy, I shall restrict myself still more, referring only to certain matters affecting externally visible peculiarities. The trunk of the elephant differs somewhat from other nasal prolongations, such as the snouts of certain insectivora, which are simply development of the nasal cartilages. The nasal cartilages in the Proboscidea serve merely as valves to the entrance of the bony nares, the trunk itself being only a pipe or duct leading to them, composed of powerful muscular and membranous tissue and consisting of two tubes, separated by a septum. The muscles in front (levatores proboscidis), starting from the frontal bone, run along a semicircular line, arching upwards above the nasal bones and between the orbits. They are met at the sides by the lateral longitudinal muscles, which blend, and their fibres run the whole length of the proboscis down to the extremity. The depressing muscles (depressores proboscidis), or posterior longitudinals, arise from the anterior surface and lower border of the premaxillaries, and form "two layers of oblique fasciculi along the posterior surface of the proboscis; the fibres of the superficial set are directed downwards and outwards from the middle line. They do not reach the extremity of the trunk, but disappear by curving over the sides a little above the end of the organ. The fibres of the deeper set take the reverse direction, and are attached to a distinct tendinous raphe along the posterior median line" ('Anat. Ind. Elep.,' Miall and Greenwood). These muscles form the outer sheath of other muscles, which radiate from the nasal canals outwards, and which consist of numerous distinct fasciculi. Then there are a set of transverse muscles in two parts—one narrow, forming the septum or partition between the nasal passages, and the other broader between the narrow part and the posterior longitudinal muscles.

When we consider the bulk of these well-knit muscles we can no longer wonder at the power of which this organ is capable, although, according to Mr. Sanderson, its capabilities are much exaggerated; and he explodes various popular delusions concerning it. He doubts the possibility of the animal picking up a needle, the common old story which I also disbelieve, having often seen the difficulty with which a coin is picked up, or rather scraped up; but he quite scouts the idea of an elephant being able to lift a heavy weight with his trunk, giving an instance recorded of one of these creatures lifting with his trunk the axle of a field-piece as the wheel was about to pass over a fallen gunner, which he declares to be a physical impossibility. Certainly the story has many elements of improbability about it, and his comments on it are caustic and amusing: par exemple, when he asks: "How did the elephant know that a wheel going over the man would not be agreeable to him?" That is the weak point in the story—but, however intelligent the animal might be, Mr. Sanderson says it is physically impossible.

Another thing that strikes every one is the noiseless tread of this huge beast. To describe the mechanism of the foot of the elephant concisely and simply I am going to give a few extracts from the observations of Professor W. Boyd Dawkins and Messrs. Oakley, Miall, and Greenwood: "It stands on the ends of its five toes, each of which is terminated by comparatively small hoofs, and the heel-bone is a little distance from the ground. Beneath comes the wonderful cushion composed, of membranes, fat, nerves, and blood-vessels, besides muscles, which constitutes the sole of the foot" (W. B. D. and H. O.). "Of the foot as a whole—and this remark apples to both fore and hind extremities—the separate mobility of the parts is greater than would be suspected from an external inspection, and much greater than in most Ungulates. The palmar and plantar soles, though thick and tough, are not rigid boxes like hoofs, but may be made to bend even by human fingers. The large development of muscles acting upon the carpus and tarsus, and the separate existence of flexors and extensors of individual digits, is further proof that the elephant's foot is far from being a solid unalterable mass. There are, as has been pointed out, tendinous or ligamentous attachments which restrain the independent action of some of these muscles, but anatomical examinations would lead us to suppose that the living animal could at all events accurately direct any part of the circumference of the foot by itself to the ground. The metacarpal and metatarsal bones form a considerable angle with the surface of the sole, while the digits, when supporting the weight of the body, are nearly horizontal" (M. and G.). This formation would naturally give elasticity to the foot, and, with the soft cushion spoken of by Professor Dawkins, would account for the noiselessness of the elephant's tread. On one occasion a friend and myself marched our elephant up to a sleeping tiger without disturbing the latter's slumbers.

It is a curious fact that twice round an elephant's foot is his height; it may be an inch one way or the other, but still sufficiently near to take as an estimate.

Now we come to a third peculiarity in this interesting animal, and that is the power of withdrawing water or a similar fluid from apparently the stomach by the insertion of its trunk into the mouth, which it sprinkles over its body when heated. The operation and the modus operandi are familiar to all who have made much use of elephants, but the internal economy by which the water is supplied is as yet a mystery to be solved, although various anatomists have given the subject serious attention. It is generally supposed that the receptacle for the liquid is the stomach, from the quantity that is ejected. An elephant distressed by a long march in the heat of the sun withdraws several quarts of water, but that it is water, and not a secretion produced by salivatory glands, is not I think sufficiently evident. In talking over the matter with Mr. Sanderson, he informed me that an elephant that has drunk a short time before taking an arduous march has a more plentiful supply of liquid at his disposal. Therefore we might conclude that it is water which is regurgitated, and in such quantity as to preclude the idea of its being stored anywhere but in the stomach; but the question is, how it is so stored there without assimulating with the food in the process of digestion. Sir Emerson Tennent, in his popular and well-known, but in some respects incorrect, account of the elephant, has adopted the theory that the cardiac end of the stomach is the receptacle for the water; and he figures a section of it showing a number of transverse circular folds; and he accepts the conclusion arrived at by Camper and Sir Everard Home that this portion can be shut off as a water chamber by the action of the fold nearest to the oesophagus; but these folds are too shallow to serve as water-cells, and it has not been demonstrated that the broadest fold near the oesophagus can be contracted to such an extent as to form a complete diaphragm bisecting the stomach. Messrs. Miall and Greenwood say: "The stomach is smooth, externally elongate, and nearly straight. The cardiac end is much prolonged and tapering. A number of transverse, nearly circular, folds project inwards from the cardiac wall; they almost disappear when the stomach is greatly distended, and are at all times too shallow to serve as water-cells, though they have been figured and described as such."

That the stomach is the reservoir is, I think, open to doubt; but there is no other possible receptacle as yet discovered, though I shall allude to a supposed one presently, which would hold a moderate supply of water, and further research in this direction is desirable. Most of the dissections hitherto made have been of young and immature specimens. Dr. Watson's investigations have thrown some light on the way in which the water is withdrawn, which differs from Dr. Harrison's conclusions, which are quoted by Sir Emerson Tennent. Dr. Watson says regarding this power of withdrawal: "It is evident that were the throat of this animal similar to that of other mammals, this could not be accomplished, as the insertion of a body, such as the trunk, so far into the pharynx as to enable the constrictor muscles of that organ to grasp it, would at once give rise to a paroxysm of coughing; or, were the trunk merely inserted into the mouth, it would be requisite that this cavity be kept constantly filled with water, at the same time that the lips closely encircled the inserted trunk. The formation of the mouth of the elephant, however, is such as to prevent the trunk ever being grasped by the lips so as effectually to stop the entrance of air into the cavity, and thus at once, if I may so express it, the pump action of the trunk is completely paralysed. We find, therefore, that it is to some modification of the throat that we must look for an explanation of the function in question." He then goes on to explain minutely the anatomical details of the apparatus of the throat, which I will endeavour to sketch as simply, though clearly, as I can. The superior aperture of the pharynx is extremely narrow, so much so as to admit, with difficulty, the passage of a closed fist; but immediately behind this the pharynx dilates into a large pouch capable of containing a certain quantity of fluid—according to Dr. Watson a considerable quantity; but this is open to question. Professor Miall states that in the young specimen examined by him and Mr. Greenwood, a pint was the capacity of the pouch. However, according to Dr. Watson, it is capable of distention to a certain extent. The pouch is prolonged forward beneath the root of the tongue, which forms the anterior boundary, whilst the posterior wall is completed by depression of the soft palate; when the latter is elevated the pouch communicates freely with the oesophagus. I omit Dr. Watson's minute description of the anatomy of this part in detail, which the reader who cares to study the matter more deeply can find in his 'Contributions to the Anatomy of the Indian Elephant,' 'Journal of Anatomy and Physiology,' 1871-74, but proceed to quote some of his deductions from the observations made: "An elephant can," he says, "as the quotations sufficiently prove, withdraw water from his stomach in two ways—first, it may be regurgitated directly into the nasal passages by the action of the diaphragm and abdominal muscles, the soft palate being at the same time depressed, so as to prevent the passage of water into the mouth. Having in this manner filled the large nasal passages communicating with the trunk, the water contained in them is then forced through the trunk by means of a powerful expiration; or, in the second place, the water may be withdrawn from the cavity of the mouth by means of the trunk inserted into it."

The second deduction is, I think, the more probable one. Before an elephant spirts water over his body, he invariably puts his trunk into his mouth for the liquid, whatever it may be. Messrs. Miall and Greenwood are also against the former supposition, viz. that the fluid is regurgitated into the nasal passages. They say: "We are disposed to question the normal passage of water along this highly-sensitive tract. Examination of the parts discovers no valve or other provision for preventing water, flowing from behind forward, from gaining free entrance into the olfactory recesses." Mr. Sanderson, in discussing the habits of elephants with me, informed me that, from his observations, he was sure that an elephant, in drawing up water, did not fill more than fifteen to eighteen inches of his trunk at a time, which confirms the opinion of the two last-mentioned authors. Now we go on with Dr. Watson's second deduction:—

"It is manifestly impossible that the water can be contained within the cavity of the mouth itself, as I have already shown that the lips in the elephant are so formed as effectually to prevent this. The water regurgitated is, however, by means of the elevation of the soft palate, forced into the pharyngeal pouch. The superior aperture of this pouch being much narrower than the diameter of the pouch itself, and being completely surrounded by the muscular fibres of the stylo-glossus on each side, and the root of the tongue in front, which is prolonged backwards so as to form a free sharp margin, we have thus, as it were, a narrow aperture surrounded by a sphincter muscle, into which the trunk being inserted, and grasped above its dilated extremity by the sphincter arrangement just referred to, air is thus effectually excluded; and, the nasal passages being then exhausted by the act of inspiration, water is lodged within these passages, to be used as the animal thinks fit, either by throwing it over his body, or again returning it into his mouth."

This is doubtless a correct conclusion. The question still remaining open is, What is the fluid—water or a secretion? If water, where is it stowed in sufficient quantity? The testimony of several eminent anatomists appears to be against stomach complications such as before suggested. Dr. Anderson has told me that he had the opportunity of examining the stomachs of two very large elephants, which were perfectly simple, of enormous size; and he was astonished at the extent of mucous surface. If water were drawn from such a stomach, it would be more or less tainted with half-digested food, besides which, when drunk, it would be rapidly absorbed by the mucous surfaces. I think therefore that we may assume that these yield back a very fluid secretion, which is regurgitated, as before suggested, into the pharyngeal pouch, to be withdrawn as required. Sir Emerson Tennent figures, on the authority of Dr. Harrison, a portion of the trachea and oesophagus, connected by a muscle which he supposes "might raise the cardiac orifice of the stomach, and so aid this organ to regurgitate a portion of its contents into the oesophagus," but neither Dr. Watson nor Messrs. Miall and Greenwood have found any trace of this muscle.

Before proceeding to a detailed account of the Indian elephant, I will cursorily sketch the difference between it and its African brother.

The African elephant is of larger size as a rule, with enormously developed ears, which quite overlap his withers. The forehead recedes, and the trunk is more coarsely ringed; the tusks are larger, some almost reaching the size of those mentioned above in the fossil head at the museum. An old friend of mine, well known to all the civilised—and a great portion of the uncivilised—world, Sir Samuel Baker, had, and may still have, in his possession a tusk measuring ten feet nine inches. This of course includes the portion within the socket, whereas my measurement of the fossil is from the socket to tip.

The lamination of the molar teeth also is very distinct in the two species, as I have before stated—the African being in acute lozenges, the Indian in wavy undulations.

Another point of divergence is, that the African elephant has only three nails on the hind feet, whereas the Asiatic has four.

NO. 425. ELEPHAS INDICUSThe Indian or Asiatic Elephant (Jerdon's No. 211)NATIVE NAMES.—Hasti or Gaja, Sanscrit; Gaj, Bengali; Hati, Hindi; Ani in Southern India, i.e. in Tamil, Telegu, Canarese, and Malabari; Feel, Persian; Allia, Singhalese; Gadjah, Malayan; Shañh, Burmese.

HABITAT.—India, in most of the large forests at the foot of the Himalayas from Dehra Doon down to the Bhotan Terai; in the Garo hills, Assam; in some parts of Central and Southern India; in Ceylon and in Burmah, from thence extending further to Siam, Sumatra and Borneo.

DESCRIPTION.—Head oblong, with concave forehead; small ears as compared with the African animal; small eyes, lighter colour, and four instead of three nails on the hind foot; the laminations of the molar teeth in wavy undulations instead of sharp lozenges, as in the African, the tusks also being much smaller in the female, instead of almost equal in both sexes.

SIZE.—The maximum height appears to be about 11 feet, in fact the only authentic measurement we have at present is 10 feet 7 inches.

"The huge elephant, wisest of brutes,"has had a good deal of the romance about it taken away by modern observers. The staid appearance of the animal, with the intellectual aspect contributed by the enormous cranial development, combined with its undoubted docility and aptitude for comprehending signs, have led to exaggerated ideas of its intelligence, which probably does not exceed that of the horse, and is far inferior to that of the dog. But from time immemorial it has been surrounded by a halo of romance and exaggeration. Mr. Sanderson says, however, that the natives of India never speak of it as an intelligent animal, "and it does not figure in their ancient literature for its wisdom, as do the fox, the crow, and the monkey;" but he overlooks the fact that the Hindu god of wisdom, Gunesh, is always depicted with the body of a man, but the head of an elephant. However this is apparently an oversight, for both in his book and lecture he alludes to Gunesh. The rest of his remarks are so good, and show so much practical knowledge, that I shall take the liberty of quoting in extenso from a lecture delivered by him at Simla last year, a printed copy of which he kindly sent me, and also from his interesting book, 'Thirteen Years amongst the Wild Beasts.'

He says: "One of the strongest features in the domesticated elephant's character is its obedience. It may also be readily taught, as it has a large share of the ordinary cultivable intelligence common in a greater or less degree to all animals. But its reasoning faculties are undoubtedly far below those of the dog, and possibly of other animals; and in matters beyond the range of its daily experience it evinces no special discernment. Whilst quick at comprehending anything sought to be taught to it, the elephant is decidedly wanting in originality."

I think one as often sees instances of decided stupidity on the part of elephants as of sagacity, but I think the amount of intelligence varies in individuals. I have known cases where elephants have tried to get their mahouts off their backs—two cases in my own district—in the one the elephant tried shaking and then lying down, both of which proved ineffectual; in the other it tried tearing off the rafters of a hut and throwing them over its back, and finally rubbing against low branches of trees, which proved successful. The second elephant, I think, showed the greatest amount of original thought; but there is no doubt the sagacity of the animal has been greatly overrated. I quote again from Mr. Sanderson, whose remarks are greatly to the point:—

"What an improbable story is that of the elephant and the tailor, wherein the animal, on being pricked with a needle instead of being fed with sweetmeats as usual, is represented as having deliberately gone to a pond, filled its trunk with dirty water, and returned and squirted it over the tailor and his work! This story accredits the elephant with appreciating the fact that throwing dirty water over his work would be the peculiar manner in which to annoy a tailor. How has he acquired the knowledge of the incongruity of the two things, dirty water and clean linen? He delights in water himself, and would therefore be unlikely to imagine it objectionable to another. If the elephant were possessed of the amount of discernment with which he is commonly credited, is it reasonable to suppose that he would continue to labour for man instead of turning into the nearest jungle? The elephant displays less intelligence in its natural state than most wild animals. Whole herds are driven into ill-concealed inclosures which no other forest creatures could be got to enter; and single ones are caught by being bound to trees by men under cover of a couple of tame elephants, the wild one being ignorant of what is going on until he finds himself secured. Escaped elephants are re-taken without trouble; even experience does not bring them wisdom. Though possessed of a proboscis which is capable of guarding it against such dangers, the wild elephant readily falls into pits dug in its path, whilst its fellows flee in terror, making no effort to assist the fallen one, as they might easily do by kicking in the earth around the pit. It commonly happens that a young elephant falls into a pit, in which case the mother will remain until the hunters come, without doing anything to assist her offspring—not even feeding it by throwing in a few branches.

"When a half-trained elephant of recent capture happens to get loose, and the approach of its keeper on foot might cause it to move off, or perhaps even to run away altogether, the mahout calls to his elephant from a distance to kneel, and he then approaches and mounts it. The instinct of obedience is herein shown to be stronger than the animal's intelligence. When a herd of wild elephants is secured within a stockade, or kheddah, the mahouts ride trained elephants amongst the wild ones without fear, though any one of the wild ones might, by a movement of its trunk, dislodge the man. This they never do."