полная версия

полная версияNatural History of the Mammalia of India and Ceylon

On the other hand we do hear of wonderful cases of reasoning on the part of these creatures. I have never seen anything very extraordinary myself; but I had one elephant which almost invariably attempted to get loose at night, and often succeeded, if we were encamped in the vicinity of sugar-cane cultivation—nothing else tempted her; and many a rupee have I had to pay for the damage done. This elephant knew me perfectly after an absence of eighteen months, trumpeted when she saw me, and purred as I came up and stroked her trunk. I then gave her the old sign, and in a moment she lifted me by the trunk on to her head. I never mounted her any other way, and, as I used to slip off by a side rope, the constant kneeling down and getting up was avoided.

Sir Emerson Tennent says: "When free in its native woods the elephant evinces rather simplicity than sagacity, and its intelligence seldom exhibits itself in cunning;" yet in the next page he goes on to relate a story told to him of a wild elephant when captured falling down, and feigning to be dead so successfully that all the fastenings were taken off; "while this was being done he and a gentleman by whom he was accompanied leaned against the body to rest. They had scarcely taken their departure and proceeded a few yards when, to their astonishment, the elephant arose with the utmost alacrity, and fled towards the jungles screaming at the top of its voice, its cries being audible long after it had disappeared in the shades of the forest." If this be correct it shows a considerable amount of cunning.

Both Mr. Sanderson and Sir Emerson Tennent agree on the subject of the rarity of the remains of dead elephants. I have never been in real elephant country; the tracks of such as I have come across have been merely single wanderers from the Bilaspore herds, or probably elephants escaped from captivity. Forsyth once came upon the bones of a small herd of five that had been driven over a precipice from the summit of a hill, on which there was a Hindoo shrine, by the drums and music of a religious procession.

The following taken from Mr. Sanderson's lecture is interesting as regards the constitution of the herds: "Herds of elephants usually consist of from thirty to fifty individuals, but much larger numbers, even upwards of a hundred, are by no means uncommon. A herd is always led by a female, never by a male. In localities where fodder is scarce a large herd usually divides into parties of from ten to twenty. These remain at some little distance from each other, but all take part in any common movement, such as a march into another tract of forest. These separate parties are family groups, consisting of old elephants with their children and grandchildren. It thus happens that, though the gregarious instincts of elephants prompt them to form large gatherings, if circumstances necessitate it a herd breaks up under several leaders. Cases frequently occur when they are being hunted; each party will then take measures for its individual safety. It cannot be said that a large herd has any supreme leader. Tuskers never interest themselves in the movement of their herds; they wander much alone, either to visit cultivation, where the females, encumbered with young ones, hesitate to follow, or from a love of solitude. Single elephants found wandering in the forests are usually young males—animals debarred from much intimate association with the herds by stronger rivals; but they usually keep within a few miles of their companions. These wandering tuskers are only biding their time until they are able to meet all comers in a herd. The necessity for the females regulating the movements of a herd is evident, as they must accommodate the length and time of their marches, and the localities in which they rest and feed at different hours, to the requirements of their young ones."

It is a curious fact that most of the male elephants in Ceylon are what are called mucknas in India, that is, tuskless males—not one in a hundred, according to Sir Emerson Tennent, being found with tusks; nearly all, however, are provided with tushes. These, he says, he has observed them "to use in loosening earth, stripping off bark, and snapping asunder small branches and climbing plants, and hence tushes are seldom seen without a groove worn into them near their extremities." Sir Samuel Baker says that the African elephant uses his tusks in ploughing up ground in search of edible roots, and that whole acres may be seen thus ploughed, but I have never seen any use to which the Indian elephant puts his tusks in feeding. I have often watched mine peeling the bark off succulent branches, and the trunk and foot were alone used. Mr. Sanderson, in his 'Thirteen Years,' remarks: "Tusks are not used to assist the elephant in procuring food;" but he says they are formidable weapons of offence in the tusker, the biggest of whom lords it over his inferiors.

The elephant usually brings forth, after a period of gestation of from eighteen to twenty-two months, a single calf, though twins are occasionally born. Mr. Sanderson says: "Elephant calves usually stand exactly thirty-six inches at the shoulder when born, and weigh about 200 lbs. They live entirely upon milk for five or six months, when they begin to eat tender grass. Their chief support, however, is still milk for some months. I have known three cases of elephants having two calves at a birth. It cannot be said that the female elephant evinces any special attachment to her offspring, whilst the belief that all the females of a herd show affection for each other's calves is certainly erroneous. During the catching of elephants many cases occur in which young ones, after losing their mothers by death or separation, are refused assistance by the other females, and are buffeted about as outcasts. I have only known one instance of a very gentle, motherly elephant in captivity, allowing a motherless calf to suck along with her own young one. When a calf is born the mother and the herd usually remain in that place for two days. The calf is then capable of marching. Even at this tender age calves are no encumbrance to the herd's movement; the youngest climb hills and cross rivers, assisted by their dams. In swimming, very young calves are supported by their mothers' trunks, and are held in front of them. When they are a few months old they scramble on to their mother's shoulders, and hold on with their fore-legs, or they swim alone. Though a few calves are born at other seasons, the largest number make their appearance about September, October, and November."

Until I read the above I, from my limited experience, had come to the conclusion that elephant mothers are very fussy and jealous of other females. (See Appendix C.)

I have only once seen an elephant born in captivity, and that was in 1859, when I was in charge of the Sasseram Levy on the Grand Trunk road. Not far from the lines of my men was an elephant camp; they were mostly Burmese animals, and many of them died; but one little fellow made his appearance one fine morning, and was an object of great interest to us all. On one occasion, some years after, I went out after a tiger on a female elephant which had a very young calf. I repented it after a while, for I lost my tiger and my temper, and very nearly my life. Those who have read 'Seonee,' may remember the ludicrous scene in which I made the doctor figure as the hero. An elephant is full grown at twenty-five, though not in his prime till some years after. Forty years is what mahouts, I think, consider age, but the best elephants live up to one hundred years or even more.29

A propos of my remarks, in the introductory portion of this paper on Proboscidea, regarding the probable gradual extinction of the African elephant, the following reassuring paragraphs from the lecture I have so extensively quoted will prove interesting and satisfactory. Mr. Sanderson has previously alluded to the common belief, strengthened by actual facts in Ceylon, that the elephant was gradually being exterminated in India; but this is not the case, especially since the laws for their protection have come into force: "The elephant-catching records of the past fifty years attest the fact that there is no diminution in the numbers now obtainable in Bengal, whilst in Southern India elephants have become so numerous of late years that they are annually appearing where they had never been heard of before."

He then instances the Billigarungun hills, an isolated range of three hundred square miles on the borders of Mysore, where wild elephants first made their appearance about eighty years ago, the country having relapsed from cultivation into a wilderness owing to the decimation of the inhabitants by three successive visitations of small-pox. He adds: "The strict preservation of wild elephants seems only advantageous or desirable in conjunction with corresponding measures for keeping their numbers within bounds by capture. It is to be presumed that elephants are preserved with a view to their utilisation. With its jungles filled with elephants, the anomalous state of things by which Government, when obliged to go into the market, finds them barely procurable, and then only at prices double those of twenty, and quadruple those of forty years ago, will I trust be considered worthy of inquiry. Whilst it is necessary to maintain stringent restrictions on the wasteful and cruel native modes of hunting, it will I believe be found advantageous to allow lessees every facility for hunting under conditions that shall insure humane management of their captives. I believe that the price of elephants might be reduced one-half in a year or two by such measures. The most ordinary elephant cannot be bought at present for less than Rs. 2,000. Unless something be done, it is certain that the rifle will have to be called into requisition to protect the ryots of tracts bordering upon elephant jungles. To give an idea of the numbers of wild elephants in some parts of India, I may say that during the past three years 503 elephants have been captured by the Dacca kheddah establishment, in a tract of country forty miles long by twenty broad, in the Garo hills, whilst not less than one thousand more were met with during the hunting operations. Of course these elephants do not confine themselves to that tract alone, but wander into other parts of the hills. There are immense tracts of country in India similarly well stocked with wild elephants.

"I am sure it will be regarded as a matter for hearty congratulation by all who are interested in so fine and harmless an animal as is the elephant that there is no danger of its becoming extinct in India. Though small portions of its haunts have been cleared for tea or coffee cultivation, the present forest area of this country will probably never be practically reduced, for reasons connected with the timber supply and climate of the country; and as long as its haunts remain the elephant must flourish under due regulations for its protection."

Elephants are caught in various ways. The pitfall is now prohibited, so also is the Assam plan of inclosing a herd in a salt lick. Noosing and driving into a kheddah or inclosure are now the only legitimate means of capture. The process is too long for description here, but I may conclude this article, which owes so much to Mr. Sanderson's careful observations, with the following interesting account of the mode in which the newly-caught elephant is taught to obey:—

"New elephants are trained as follows: they are first tied between two trees, and are rubbed down by a number of men with long bamboos, to an accompaniment of the most extravagant eulogies of the animal, sung and shouted at it at the top of their voices. The animal of course lashes out furiously at first; but in a few days it ceases to act on the offensive, or, as the native say, 'shurum lugta hai'—'it becomes ashamed of itself,' and it then stands with its trunk curled, shrinking from the men. Ropes are now tied round its body, and it is mounted at its picket for several days. It is then taken out for exercise, secured between two tame elephants. The ropes still remain round its body to enable the mahout to hold on should the elephant try to shake him off. A man precedes it with a spear to teach it to halt when ordered to do so; whilst, as the tame elephants wheel to the right or left, the mahout presses its neck with his knees, and taps it on the head with a small stick, to train it to turn in the required direction. To teach an elephant to kneel it is taken into water about five feet deep when the sun is hot, and, upon being pricked on the back with a pointed stick it soon lies down, partly to avoid the pain, partly from inclination for a bath. By taking it into shallower water daily, it is soon taught to kneel even on land.

"Elephants are taught to pick up anything from the ground by a rope, with a piece of wood attached, being dangled over their foreheads, near to the ground. The wood strikes against their trunk and fore-feet, and to avoid the discomfort the elephant soon takes it in its trunk, and carries it. It eventually learns to do this without a rope being attached to the object."

Sir Emerson Tennent's account of the practice in Ceylon is similar.

As regards the size of elephants few people agree. The controversy is as strong on this point as on the maximum size of tigers. I quite believe few elephants attain to or exceed ten feet, still there are one or two recorded instances, the most trustworthy of which is Mr. Sanderson's measurement of the Sirmoor Rajah's elephant, which is 10 ft. 7½ in. at the shoulder—a truly enormous animal. I have heard of a tusker at Hyderabad that is over eleven feet, but we must hold this open to doubt till an accurate measurement, for which I have applied, is received. Elephants should be measured like a horse, with a standard and cross bar, and not by means of a piece of string over the rounded muscles of the shoulder. Kellaart, usually a most accurate observer, mentions in his 'Prodromus Faunæ Zeylanicæ' his having measured a Ceylon elephant nearly twelve feet high, but does not say how it was done. Sir Joseph Fayrer has a photograph of an enormous elephant belonging to the late Sir Jung Bahadur, a perfect mountain of flesh.

We in India have nothing to do with the next order, HYRACOIDEA or Conies, which are small animals, somewhat resembling short-eared rabbits, but which from their dentition and skeleton are allied to the rhinoceros and tapir. The Syrian coney is frequently mentioned in the Old Testament, and was one of the animals prohibited for food to the Jews, "because he cheweth the cud and divideth not the hoof." The chewing of the cud was a mistake, for the coney does not do so, but it has a way of moving its jaws which might lead to the idea that it ruminates. In other parts of Scripture the habits of the animal are more accurately depicted—"The rocks are a refuge for the conies;" and again: "The conies are but a feeble folk, yet make they their houses in the rocks." Solomon says in the Proverbs: "There be four things which are little upon the earth, but they are exceeding wise." These are the ants, for they prepare their meat in summer, as we see here in India the stores laid up by the large black ant (Atta providens); the conies for the reason above given; the locusts, which have no king, yet go forth by bands; and the spider, which maketh her home in kings' palaces.

ORDER UNGULATA

These are animals which possess hoofs; and are divided into two sub-orders—those that have an odd number of toes on the hind-foot, such as the horse, tapir, and rhinoceros, being termed the PERISSODACTYLA; and the others, with an even number of toes, such as the pig, sheep, ox, deer, &c., the ARTIODACTYLA; both words being taken from the Greek perissos and artios, uneven or overmuch, and even; and daktulos, a finger or toe. We begin with the uneven-toed group.

SUB-ORDER PERISSODACTYLAThis consists of three living and two extinct families—the living ones being horses, tapirs, and rhinoceroses, and the extinct the Paleotheridæ and the Macrauchenidæ. I quote from Professor Boyd Dawkins and Mr. H. W. Oakley the following brief yet clear description of the characteristics of this sub-order:—

"In all the animals belonging to the group the number of dorso-lumbar vertebræ is not fewer than twenty-two; the third or middle digit of each foot is symmetrical; the femur or thigh-bone has a third trochanter, or knob of bone, on the outer side; and the two facets on the front of the astragalus or ankle-bone are very unequal. When the head is provided with horns they are skin deep only, without a core of bone, and they are always placed in the middle line of the skull, as in the rhinoceros.

"In the Perissodactyla the number of toes is reduced to a minimum. Supposing, for example, we compare the foot of a horse with one of our own hands, we shall see that those parts which correspond with the thumb and little finger are altogether absent, while that which corresponds with the middle finger is largely developed, and with its hoof, the equivalent to our nail, constitutes the whole foot. The small splint bones, however, resting behind the principal bone of the foot represent those portions (metacarpals) of the second and third digits which extend from the wrist to the fingers properly so-called, and are to be viewed as traces of a foot composed of three toes in an ancestral form of the horse, which we shall discuss presently. In the tapir the hind foot is composed of three well-developed toes, corresponding to the first three toes in man, and in the rhinoceros both feet are provided with three toes, formed of the same three digits. In the extinct Paleotherium also the foot is constituted very much as in the rhinoceros."

FAMILY EQUIDÆ—THE HORSE

This family consists of the true horses and the asses, which latter also include the zebra and quagga. Apart from the decided external differences between the horse and ass, they have one marked divergence, viz. that the horse has corns or callosities on the inner side of both fore and hind limbs, whilst the asses have them only on the fore limbs; but this is a very trifling difference, and how closely the two animals are allied is proved by the facility with which they interbreed. It is, therefore, proper to include them both in one genus, although Dr. Gray has made a separation, calling the latter Asinus, and Hamilton Smith proposed Hippotigris as a generic name for the zebras.

We have no wild horse in India; in fact there are no truly wild horses in the world as far as we know. The tarpan or wild horse of Tartary, and the mustang of South America, though de facto wild horses, are supposed to be descended from domesticated forms. In Australia too horses sometimes grow wild from being left long in the bush. These are known as brumbies, and are generally shot by the stock farmer, as they are of deteriorated quality, and by enticing away his mares spoil his more carefully selected breeds. According to Mr. Anthony Trollope they are marvels of ugliness.

The Indian species of this genus are properly asses; there are two kinds, although it has been asserted by many—and some of them good naturalists, such as Blyth—that the Kiang of Thibet and the Ghor-khur of Sind and Baluchistan are the same animal.

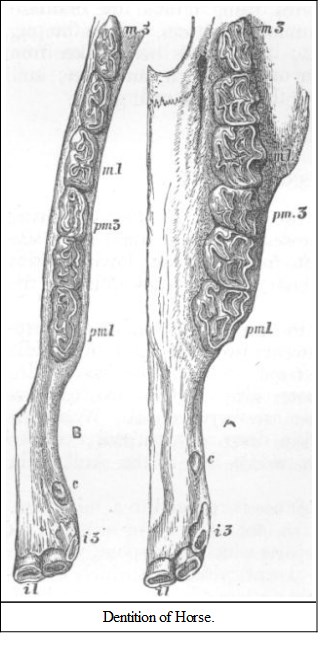

GENUS EQUUSIncisors, 6/6; canines, 1—1/1—1; molars, 6—6/6—6; these last are complex, with square crowns marked by wavy folds of enamel. The incisors are grooved, and are composed of folds of enamel and cement, aptly described by Professor Boyd Dawkins and Mr. Oakley as being folded in from the top, after the manner of the finger of a glove the top of which has been pulled in. The marks left by the attrition of the surface give an approximate idea of the age of the animal. The stomach is simple—the intestinal canal very long and cæcum enormous.

NO. 426. EQUUS ONAGERThe Wild Ass of Kutch (Jerdon's No. 214)NATIVE NAMES.—Ghor-khur, Hindi; Ghour, or Kherdecht, Persian; Koulan of the Kirghiz.

HABITAT.—Sind, Baluchistan, Persia.

DESCRIPTION.—Pale sandy colour above, with a slight rufescent tinge; muzzle, breast, lower parts and inside of limbs white; a dark chocolate brown dorsal stripe from mane to tail, with a cross on the shoulder, sometimes a double one; and the legs are also occasionally barred. The mane and tail-tuft are dark brown or black; a narrow dark band over the hoof; ears longish, white inside, concolorous with the body outside, the tip and outer border blackish; head heavy; neck short; croup higher than the withers.

SIZE.—Height about 11 to 12 hands.

The following account I extract from Jerdon's 'Mammals of India,' p. 238, which epitomises much of what has been written on the subject:—

"The ghor-khur is found sparingly in Cutch, Guzerat, Jeysulmeer and Bikaneer, not being found further south, it is said, than Deesa, or east of 75° east longitude. It also occurs in Sind, and more abundantly west of the Indus river, in Baluchistan, extending into Persia and Turkestan, as far north as north latitude 48°. It appears that the Bikaneer herd consists at most of about 150 individuals, which frequent an oasis a little elevated above the surrounding desert, and commanding an extensive view around. A writer in the Indian Sporting Review, writing of this species as it occurs in the Pât, a desert country between Asnee and the hills west of the Indus, above Mithunkote, says: 'They are to be found wandering pretty well throughout the year; but in the early summer, when the grass and the water in the pools have dried up from the hot winds (which are here terrific), the greater number, if not all, of the ghor-khurs migrate to the hills for grass and water. The foaling season is in June, July, and August, when the Beluchis ride down and catch numbers of foals, finding a ready sale in the cantonments for them, as they are taken down on speculation to Hindustan. They also shoot great numbers of full-grown ones for food, the ground in places in the desert being very favourable for stalking.' In Bikaneer too, according to information given by Major Tytler to Mr. Blyth: 'Once only in the year, when the foals are young, a party of five or six native hunters, mounted on hardy Sindh mares, chase down as many foals as they succeed in tiring, which lie down when utterly fatigued, and suffer themselves to be bound and carried off. In general they refuse sustenance at first, and about one-third only of those taken are reared; but these command high prices, and find a ready sale with the native princes. The profits are shared by the party, who do not attempt a second chase in the same year, lest they should scare the herd from the district, as these men regard the sale of a few ghor-khurs annually as a regular source of subsistence.'

"This wild ass is very shy and difficult to approach, and has great speed. A full-grown one has, however, been run down fairly and speared more than once."

I remember we had a pair of these asses in the Zoological Gardens at Lahore in 1868; they were to a certain extent tame, but very skittish, and would whinny and kick on being approached. I never heard of their being mounted.

It is closely allied to, if not identical with, the wild ass of Assyria (Equus hemippus). The Hon. Charles Murray, who presented one of the pair in the London Zoological Gardens in 1862, wrote the following account of it to Dr. Sclater: "The ghour or kherdecht of the Persians is doubtless the onager of the ancients. Your specimen was caught when a foal on the range of mountains which stretch from Kermanshah on the west in a south-easterly direction to Shiraz; these are inhabited by several wild and half-independent tribes, the most powerful of which are the Buchtzari. The ghour is a remarkably fleet animal, and moreover so shy and enduring that he can rarely be overtaken by the best mounted horsemen in Persia. For this reason they chase them now, as they did in the time of Xenophon, by placing relays of horsemen at intervals of eight or ten miles. These relays take up the chase successively and tire down the ghour. The flesh of the ghour is esteemed a great delicacy, not being held unclean by the Moslem, as it was in the Mosaic code. I do not know whether this species is ever known to bray like the ordinary domestic ass. Your animal, whilst under my care, used to emit short squeaks and sometimes snorts not unlike those of a deer, but she was so young at the time that her voice may not have acquired its mature intonation."