полная версия

полная версияNatural History of the Mammalia of India and Ceylon

SIZE.—Head and body, about 18 inches; tail, with hair about 5 inches.

This hare was first described by Hodgson ('J. A. S. B.,' vol. xi.), who also gave a plate; but there is a full description with an excellent plate in Blanford's 'Scientific Results of the Second Yarkand Mission.'

NO. 412. LEPUS TIBETANUSThe Thibet HareHABITAT.—Little Thibet; Ladakh.

DESCRIPTION.—Ears longer than the head, margined with yellow white internally, externally, with the apex, edged with black and with a narrow edging of black extending about half-way down the hinder margin. The general colour seems to vary, as is the case with most of the mountain hares. According to Waterhouse it is "palish-ashy grey; the back mottled with dusky and yellowish-white; the back of neck pale rufous brown." Two specimens, described by Blanford, are "general colour rufous brown (very dark brownish tawny)," and another, "above dusky brown, with an ashy tinge on the rump." Waterhouse's specimens may have been in the winter dress; the under-parts are white; legs longish and white; tail white, with the upper surface sooty or grey-black. The excellent plate in the Yarkand Report is nearer to Waterhouse's verbal portraiture, being of a mottled ashy grey.

SIZE.—Head and body, about 18 inches; tail, with hair, 4½ inches.

NO. 413. LEPUS YARKANDENSISThe Yarkand HareNATIVE NAME.—Toshkhan, Yarkandi.

HABITAT.—The plains of Yarkand and Kashghar.

DESCRIPTION.—General colour sandy, more or less mixed with dusky; pale isabelline on the sides; no grey on rump; tail dark brown above; ears without black tip; lower parts white; fur soft and long; fore-legs very pale, brown in front; hind-legs still paler, brown outside.

SIZE.—Head and body, about 17 inches; tail, 4 inches.

Mr. Blanford remarks that "one striking peculiarity of this very pale coloured hare is the absence of any black patches, and of all grey coloration throughout." The specimens were all shot in winter too. (See Blanford's 'Scientific Results, Second Yarkand Mission,' p. 65, and plate iv., fig. 1.)

NO. 414. LEPUS PAMIRENSISThe Pamir HareHABITAT.—Lake Sirikal, Pamir.

DESCRIPTION.—Pale sandy brown; almost isabelline on back and sides; rump greyish-white; tail black above; face and anterior portion of the ears concolorous with back; terminal portion of ears black outside at the edge; breast light rufous; lower parts white; fur fine, close and soft; fore-legs in front, and hind-legs outside, with a light brownish tinge.

SIZE.—Head and body, about 17 inches; tail, 4 inches.

The hare is described and named by Mr. W. T. Blanford, and from his full description I have abridged the above short notice. It is also well figured in the 'Yarkand Report,' plate v., fig. 1.

NO. 415. LEPUS STOLICZKANUSStoliczka's HareHABITAT.—Kashghar, Altum Artush district, north-east of Kashghar.

DESCRIPTION.—"General colour light sandy brown, much mixed with black on the back; the rump very little paler; tail rather long, black above; face and anterior portion of ears the same colour as the back; terminal portion of ears black outside; nape and breast light rufous; lower parts white. The skull differs much from that of L. Yarkandensis and L. Pamirensis, the nasals being much more abruptly truncated behind than in either, and the parietal region or sinciput flatter" (Blanford's 'Scientific Results, Second Yarkand Mission,' p. 69, and plate v. fig. 2, skull plate, Va. fig. 2).

SIZE.—Head and body, about 17 inches; tail, with hair, 5 inches.

This hare was obtained by Dr. Stoliczka, and was first described and named by Mr. W. T. Blanford ('J. A. S. B.' vol. xiv. 1875, part ii. p. 110).

NO. 416. LEPUS CRASPEDOTISThe Large-eared HareHABITAT.—Baluchistan, Pishin.

DESCRIPTION.—Colour brown above, white below; the fur of the back is very pale French grey at the base, then black, and the tip is pale brown, almost isabelline; the black rings are wanting on the nape, hind neck and breast, which, like the fore-legs and hinder part of the tarsi are pale rufous brown; ears externally mouse brown, blackish-brown on the posterior portion near the tip, the anterior edges white, with rather longer hairs, except near the tip, where the hair is short and black; the posterior margins inside pale isabelline, the pale edge becoming broader near the tip; tail black above, white on the sides and below; whiskers black near the base, white except in the shorter ones throughout the greater part of their length; a pale line from the nose, including the eye, continued back nearly to the ear (Blanford's 'Eastern Persia,' vol. ii. p. 81, with plate).

SIZE.—Head and body, 15 inches; tail, with hair, 4·5 inches; ear, 6 inches; breadth of ear laid flat, 3·25 inches.

This is a new species, described and named by Mr. W. T. Blanford.

NO. 417. LEPUS HISPIDUSThe Hispid HareHABITAT.—The Terai and low forests at the base of the Himalayas.

DESCRIPTION.—"General colour dark or iron grey, with an embrowned ruddy tinge, and the limbs shaded outside, like the body, with black, instead of being unmixed rufous" (Hodgson). The inner fur is soft, downy, and of an ash colour, the outer longer, hispid, harsh and bristly. Some of the hairs ringed black and brown, others are pure black and long, the latter more numerous; ears short and broad.

SIZE.—Head and body, 19½ inches; tail, with hair, 2-1/8 inches; ears, 2¾ inches.

This animal seems to be a link between the hares and the rabbits. Like the latter, it burrows, and has more equal limbs; but, according to Hodgson, it is not gregarious, but lives in pairs. It would greatly help in the identification of its position if some one would procure the young or a gravid female, and see whether the young are born blind and naked as in the rabbits, or open-eyed and clad with fur as in the hares. Jerdon says it is common at Dacca, and is reported to be found also in the Rajmehal hills, and that its flesh is stated to be white, like that of the rabbit.

FAMILY LAGOMYIDÆ—THE PIKAS, OR MOUSE-HARESOne or two premolars above and below; grinding teeth as in Leporidæ; skull depressed; the frontals are contracted, without the wing-like processes of the hares; a single perforation in the facial surface of the maxillaries; a curious prolongation of the posterior angle of the malar into a process extending almost to the ear tube, or auditory meatus; the basisphenoid is not perforated and separated from the vomer as in Lepus; the coronoid process is in the form of a tubercle; the clavicles are complete; ears short; limbs nearly equal; no tail.

GENUS LAGOMYSAnimals of small size and robust form; short-eared and tailless; two premolars above and below.

NO. 418. LAGOMYS ROYLEIRoyle's Pika (Jerdon's No. 210)NATIVE NAME.—Rang-runt, or Rang-duni, in Kunawur.—Jerdon.

HABITAT.—The Himalayan range, from Kashmir to Sikim.

DESCRIPTION.—Rabbit grey or brown, with a yellowish-grey tinge, more or less rufous on the head, neck, shoulder and sides of body; a hairy brown muzzle, with pale under-lip; long whiskers, some white, the posterior ones dark; under-parts white; fur soft and fine. The upper lip is lobed as in the hare; ears elliptical, with rounded tops.

SIZE.—From 6 to 8 inches.

The first specimen was sent to England by Dr. Royle, in whose honour Mr. Ogilby named it. It was obtained not far from Simla. It lives in rocky ground or amongst loose stones in burrows, and is the tailless rat described by Turner in his 'Journey to Thibet,' which had perforated the banks of a lake by its holes.

NO. 419. LAGOMYS CURZONIÆCurzon's PikaHABITAT.—The higher ranges of the Himalayas, from 14,000 to 19,000 feet. It has been found northerly in Ladakh, and easterly in Sikim.

DESCRIPTION.—Pale buff above, tinged with rufous, the sides being more rufescent; head, as far back as the ears, decidedly rufescent; ears large and oval; sides of head and nose dirty fulvous white; under-parts white, with a faint yellow tinge; limbs and soles of feet white; whiskers, some black, some white; fur long, fine and silky.

SIZE.—About 7 inches to 8 inches.

NO. 420. LAGOMYS LADACENSISThe Ladak PikaNATIVE NAMES.—Zabra, Karin, or Phisekarin, Ladakhi.

HABITAT.—High plateaux of Ladakh.

DESCRIPTION.—"General hue of the upper body pale buff, fulvous, with a very slight rufous tint, and tipped with dark brown; below whitish with translucent dusky blue."—Stoliczka, quoted by Blanford.

SIZE.—From 7 inches to 9 inches.

It is as yet doubtful whether this is not identical with the last. Mr. Blanford has separated it, and Dr. Günther, agreeing with him, named this species L. Ladacensis; but the skull characteristics of L. Curzoniæ have not as yet been compared with this, and the separation has been made on external characters only.

NO. 421. LAGOMYS AURITUSThe Large-eared PikaHABITAT.—Lukong, on the Pankong lake.

DESCRIPTION.—General colour above smoky or wood brown; the head, shoulders and rump rather paler and more rufous; lower parts whitish, with the dark basal portion of the hair showing through; fur very soft, moderately long; ears large, round, clothed rather thinly inside near the margin with whitish-brown hairs, and outside with much longer hairs of the same colour; whiskers fine and long, the upper dark brown, the lower white; feet whitish. (See Blanford's 'Sc. Res. Second Yarkand Mission,' p. 75, plate vi. fig. 2.)

SIZE.—About 8 inches.

NO. 422. LAGOMYS MACROTISThis seems to be a doubtful species; it may probably prove to be the same as the last, the skulls being similar. Mr. Blanford remarks: "I am strongly disposed to suspect, indeed, that L. auritus is the summer L. macrotis, the winter garb of the same species; but there are one or two differences which require explanation. The feet appear larger in L. macrotis, and the pads of the toes are black, whilst in L. auritus they are pale coloured. In the former the long hair of the forehead is lead black at the base, in the latter, pale grey; the feet and lower parts generally are white in L. macrotis, buffy white in L. auritus, but this may be seasonable."

NO. 423. LAGOMYS GRISEUSThe Grey PikaHABITAT.—Yarkand, Kuenlun range, south of Sunju pass.

DESCRIPTION.—General colour dull grey (almost Chinchilla colour), with a slight rufescent tinge on the face and back; lower parts white; fur very soft, about 0·9 inch long in the middle of the back; glossy leaden black at the base and for about two-thirds of its length, very pale ashy grey towards the end; the extreme tips of many hairs dark brown, and on the back the tips of all the hairs are brownish; the sides are almost pure light ashy; rump still paler; feet white; hair on the face long, light brown on the forehead, greyer on the nose, pure grey on the sides of the head. A few of the upper whiskers black, the rest white; ears large round with rather thin white hairs inside, very short hairs close to the margin, white outside, black inside, outer surface covered with whitish hairs, which become long near the base of the ear. (See Blanford's 'Scientific Results, Second Yarkand Mission,' p. 77, and plate vii. fig. 1.)

SIZE.-About 7 inches.

NO. 424. LAGOMYS RUFESCENSThe Red PikaHABITAT.—Afghanistan, Persia.

DESCRIPTION.—Pale sandy red, darker on the top of the head, the shoulders and fore part of back; two large patches behind the ears; the feet and the under-parts are pale buff yellow; ears moderately large, subovate and well clad, rusty yellow, paler on the under part; whiskers very long, brown, a few brownish white; toe-pads blackish.

SIZE.-About 8 inches.

This species has been found in the rocky hills of Cabul. Lagomys Hodgsonii, from Lahoul, Ladakh and Kulu, is considered to be the same as the above, and L. Nipalensis, described by Waterhouse, as synonymous with L. Roylei.

Under the systems of older naturalists the thick-skinned animals were lumped together under the order UNGULATA, or hoofed animals, subdivided by Cuvier into Pachydermata, or thick-skinned non-ruminants, and Ruminantia, or ruminating animals; but neither the elephant nor the coney can be called hoofed animals, and in other respects they so entirely differ from the rest that recent systematists have separated them into three distinct orders—Proboscidea, Hyracoidea and Ungulata, which classification I here adopt.

ORDER PROBOSCIDEA

It seems a strange jump from the order which contains the smallest mammal, the little harvest mouse, to that which contains the gigantic elephant—a step from the ridiculous to the sublime; yet there are points of affinity between the little mouse and the giant tusker to which I will allude further on, and which bring together these two unequal links in the great chain of nature. The order Proboscidea, or animals whose noses are prolonged into a flexible trunk, consists of one genus containing two living species only—the Indian and African Elephants. To this in the fossil world are added two more genera—the Mastodon and Dinotherium.

The elephant is one of the oldest known of animals. Frequent mention is made in the Scriptures and ancient writings of the use of ivory. In the First Book of Kings and the Second of Chronicles, it is mentioned how Solomon's ships brought every three years from Tarshish gold and silver and ivory (or elephants' teeth) apes and peacocks. In the Apocrypha the animal itself, and its use in war, is mentioned; in the old Sanscrit writings it frequently appears. Aristotle and Pliny were firm believers in the superstition which prevailed, even to more recent times, that it had no joints.

"The elephant hath joints, but none for courtesy;His legs are for necessity, not flexure"—says Shakespeare. Even down to the last century did this notion prevail, so little did people know of this animal. The supposition that he slept leaning against a tree is to be traced in Thomson's 'Seasons'—

"Or where the Ganges rolls his sacred wavesLeans the huge elephant."Again, Montgomery says—

"Beneath the palm which he was wont to makeHis prop in slumber."At a very early period elephants were used in war, not only by the Indian but the African nations. In the first Punic war (B.C. 264-241) they were used considerably by the Carthaginians, and in the second Punic war Hannibal carried thirty-seven of them across the Alps. In the wars of the Moghuls they were used extensively. The domestication of the African elephant has now entirely ceased; there is however no reason why this noble animal should not be made as useful as its Indian brother; it is a bigger animal, and as tractable, judging from the specimens in menageries. It was trained in the time of the Romans for performances in the arena, and swelled the pomp of military triumphs, when, as Macaulay, I think, in his 'Lays of Ancient Rome,' says, the people wondered at—

"The monstrous beast that hadA serpent for a hand."It seems a cruel shame, when one comes to think of it, that thousands of these noble animals should perish annually by all sorts of ignoble means—pitfalls, hamstringing, poisoned arrows, and a few here and there shot with more or less daring by adventurous sportsmen, only for the sake of their magnificent tusks.

Few people think, as they leisurely cut open the pages of a new book or play with their ivory-handled dessert-knives after dinner, of the life that has once been the lot of that inanimate substance, so beautiful in its texture, so prized from time immemorial; still less do they think, for the majority do not know, of the enormous loss of life entailed in purveying this luxury for the market. An elephant is a long-lived beast; it is difficult to say what is the extent of its individual existence; at fifty years it is in its prime, and its reproduction is in ratio slower than animals of shorter life, yet what countless herds must there be in Central Africa when we consider that the annual requirements of Sheffield alone are reported to be upwards of 46,000 tusks, which represent 23,000 elephants a year for the commerce of one single city! The African elephant must be decreasing, even as it has been extirpated in the north of that continent, where it abounded in the time of the Carthaginians, and the time may come when ivory shall be counted as one of the precious things of the past. Even now the price is going up, and is nearly double what it was a year ago. Now enhanced price means either greater demand or deficient supply, and it is probably to this last we must look for an answer to the question. True it is that if we want ivory animals must be killed to get it, for the notion that some people have gained from obsolete works on natural history, to the effect that elephants shed their tusks, is an erroneous one. It is generally supposed that elephants do not shed their tusks at all, not even milk-teeth, but that they grow ab initio, as do the incisors of rodents, from a persistent pulp, and continue growing through life. Mr. G. P. Sanderson, the author of 'Thirteen Years among the Wild Beasts,' whom I have to thank for much and valuable information about the habits of these animals, assured me, when I spoke to him about the popular idea of there being milk-tusks, that he had watched elephants from their birth, and had never known them to shed their tusks, nor had his mahouts ever found a shed tusk; but Mr. Tegetmeier has pointed out that there are skulls in the museum of the Royal College of Surgeons, showing both the milk and permanent tusks, the latter pushing forward the former, which are absorbed to a great extent, and leave nothing but a little blackened stump, the size of one's finger. This was brought to my notice by a correspondent of The Asian, "Smooth-bore," and I have lately had the pleasure of meeting Mr. Tegetmeier, and speaking to him on the subject. There is apparently no limit to the growth of tusks, so that under favourable circumstances they might attain enormous dimensions, owing to the age of the animal, and absence of the attrition which keeps the incisors of rodents down. As in the case of rodents, malformations of whose incisors I have alluded to some time back, the tusks of elephants assume various freaks. I have heard of their overlapping and crossing the trunk in a manner to impede the free use of that organ. The tusks of fossil elephants are in many cases gigantic. There is a head in the Indian Museum, of which the tusks outside the socket measure 9¾ feet, and are of very curious formation. The two run parallel some distance, and then diverge, which would lead one to suppose that the animal inhabited open country, for such a formation would be extremely uncomfortable in thick forest. That tusks of such magnitude are not found nowadays is probably due to the fact that the elephant has more enemies, the most formidable of all being man, which prevent his reaching the great age of those of the fossil periods. It may be said, by those who disbelieve in the extermination of this animal, that, as elephants have provided ivory for several thousand years, they will go on doing so; but I would remind them that in olden days ivory was an article in limited demand, being used chiefly by kings and great nobles; it is only of late years that it has increased more than a hundredfold. Our forefathers used buck-horn handled knives, and they were without the thousand-and-one little articles of luxury which are now made of ivory; even the requirements of the ancient world drove the elephant away from the coasts, where Solomon, and later still the Romans, got their ivory; and now the girdle round the remaining herds in Central Africa is being narrowed day by day. Mr. Sanderson is of opinion that it is not decreasing in India under the present restrictions, but there is no doubt the reckless slaughter of them in Ceylon has greatly diminished their numbers. Sir Emerson Tennent states that the Government reward was claimed for 3,500 destroyed in part of the northern provinces alone in three years prior to 1848, and between 1851 and 1856, 2000 were killed in the southern provinces.

GENUS ELEPHAS—THE ELEPHANT

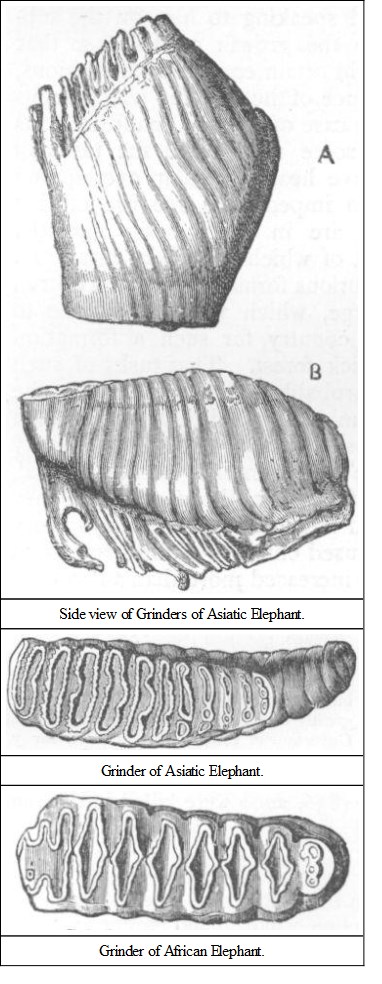

In the writings of older naturalists this animal, so singular in its construction, will be found grouped with the horse, rhinoceros, hippopotamus, tapir, coney, and pig, under the name of pachydermata, the seventh order of Cuvier, but these are now more appropriately divided, as I have said before, into three different orders—Proboscidea, the elephants; Hyracoidea, the conies; and the rest come under Ungulata. Apparently singular as is the elephant in its anatomy, it bears traces of affinity to both Rodentia and Ungulata. The composition of its massive tusks or incisors, and also of its grinders, resembles that of the Rodents. The tusks grow from a persistent pulp, which forms new ivory coated with enamel, but the grinders are composed of a number of transverse perpendicular plates, or vertical laminæ of dentine, enveloped with enamel, cemented together by layers of a substance called cortical. The enamel, by its superior hardness, is less liable to attrition, and, standing above the rest, causes an uneven grinding surface. Each of these plates is joined at the base of the tooth, and on the grinding surface the pattern formed by them distinguishes at once the Indian from the African elephant. In the former, the transverse ridges are in narrow, undulating loops, but in the African they form decided lozenges. These teeth, when worn out, are succeeded by others pushing forward from behind, and not forced up vertically, as in the case of ordinary deciduous teeth, so that it occasionally happens that the elephant has sometimes one and sometimes two grinders on each side, according to age. In the wild state sand and grit, entangled in the roots of plants, help in the work of attrition, and, according to Professor W. Boyd Dawkins, the tame animal, getting cleaner food, and not having such wear and tear of teeth, gets a deformity by the piling over of the plates of which the grinder is composed. An instance of this has come under my notice. An elephant belonging to my brother-in-law, Colonel W. B. Thomson, then Deputy Commissioner of Seonee, suffered from an aggravated type of this malformation. He was relieved by an ingenious mahout, who managed to saw off the projecting portion of the tooth, which now forms a paper-weight. In my account of Seonee I have given a detailed description of the mode in which the operation was effected.

The skull of the elephant possesses many striking features quite different from any other animal. The brain in bulk does not greatly exceed that of a man, therefore the rest of the enormous head is formed of cellular bone, affording a large space for the attachment of the powerful muscles of the trunk, and at the same time combining lightness with strength. This cellular bone grows with the animal, and is in great measure absent at birth. In the young elephant the brain nearly fills the head, and the brain-case increases but little in size during growth, but the cellular portion progresses rapidly with the growth of the animal, and is piled up over the frontals for a considerable height, giving the appearance of a bold forehead, the brain remaining in a small space at the base of the skull, close to its articulation with the neck. According to Professor Flower, the cranial cavity is elongated and depressed, more so in the African than the Indian elephant. The tentorial plane is nearly vertical, so that the cerebellar fossa is altogether behind the cerebral fossa, or, in plainer terms, the division between the big brain (cerebrum) and the little one (cerebellum) is vertical, the two brains lying on a level plane fore and aft instead of overlapping. The brain itself is highly convoluted. The nasal aperture, or olfactory fossa, is very large, and is placed a little below the brain-case. Few people who are intimate with but the external form of the elephant would suppose that the bump just above the root of the trunk, at which the hunter takes aim for the "front shot," is really the seat of the organ of smell, the channels of which run down the trunk to the orifice at the end. The maxillo-turbinals, or twisted bony laminæ within the nasal aperture, which are to be found in most mammals, are but rudimentary in the elephant—the elongated proboscis, according to Professor Flower, probably supplying their place in warming the inspired air. The premaxillary and maxillary bones are largely developed, and contain the socket of the enormous tusks. The narial aperture is thus pushed up, and is short, with an upward direction, as in the Cetacea and Sirenia, with whom the Proboscidea have certain affinities.