полная версия

полная версияNatural History of the Mammalia of India and Ceylon

Grinding teeth semi-rooted; skull rather more elongate; infra-orbital foramen of great size; clavicles imperfect, attached to the sternum, and not to the scapula; upper lip furrowed; tail not prehensile; soles of feet smooth. The female has six mammæ. In these points they differ from the American arboreal porcupines (Sphingurus), the skull of which is very short, the tail prehensile, the soles of the feet tuberculated, and the female has only four mammæ.

The two genera, Atherura and Hystrix, which compose this sub-family, are distinguished by long tail and flattened spines (Atherura); and short tail and round spines (Hystrix).

GENUS ATHERURA—THE LONG-TAILED PORCUPINENasal part of skull moderate; upper molars with one internal and three or four external folds, the latter soon separated as enamel loops; the lower teeth similar but reversed; the spines are flattened and channelled; the tail long and scaly, with a tuft of bristles at the end.

NO. 402. ATHERURA FASCICULATAThe Brush-tailed PorcupineHABITAT.—Assam, Khasia hills, Tipperah hills, Burmah, Siam, and the Malayan peninsula.

DESCRIPTION.—"The general tint of the animal is yellowish-brown, freckled with dusky brown, especially on the back; the spines, taken separately, are brown white at the root, and become gradually darker to the point; the points of the spines on the back are very dark, being of a blackish-brown colour. The long and stout bristles, which are mixed with the spines on the back, are similarly coloured" (Waterhouse, 'Mammalia,' vol. ii. p. 472). The spines are flat on the under-surface and concave on the upper, sharply pointed and broadest near the root. Mixed with the spines on the back are long bristles, very stout, projecting some three inches beyond the spines, which are only about an inch in length; below these is a scanty undergrowth of pale coloured hairs; the tail is somewhat less than half the length of the head and body, scaly, and at the end furnished with a large tuft of flattened bristles from three to four inches long, of a dirty white colour, with sometimes dusky tips; the ears are semi-ovate; whiskers long and stout, and of a brown colour; muzzle hairy; feet short, five toes, but the thumb very small, with a short rounded nail.

SIZE.—Head and body, 18 inches; tail, exclusive of tuft, 7½ inches.

Specimens of this animal were sent home to the Zoological Gardens, from Cherrapoonjee in the Khasia hills, by Dr. Jerdon. This species is almost the same as the African form (A. Africana). They are about the same in size and form and in general appearance. This last is found in such plenty, according to Bennett, in the Island of Fernando Po as to afford a staple article of food to the inhabitants. Blyth was of opinion that the Indian animal is much paler and more freckled than the African.

GENUS HYSTRIX—THE PORCUPINE"Spines cylindrical; tail short, covered with spines and slender-stalked open quills; nasal cavity usually very large; air sinuses of frontals greatly developed; teeth as in Atherura. The hind-feet with five toes; claws very stout."

The hinder part of the body is covered by a great number of sharp spines, ringed black and white, mostly tipped with white; the spines are hollow or filled with a spongy tissue, but extremely tough and resistant, with points as sharp as a needle. The animal is able to erect these by a contraction of the skin, but the old idea that they could be projected or shot out at an assailant is erroneous. They easily drop out, which may have given an idea of discharge. The porcupine attacks by backing up against an opponent or thrusting at him by a sidelong motion. I kept one some years ago, and had ample opportunity of studying his mode of defence. When a dog or any other foe comes to close quarters, the porcupine wheels round and rapidly charges back. They also have a side-way jerk which is effective.

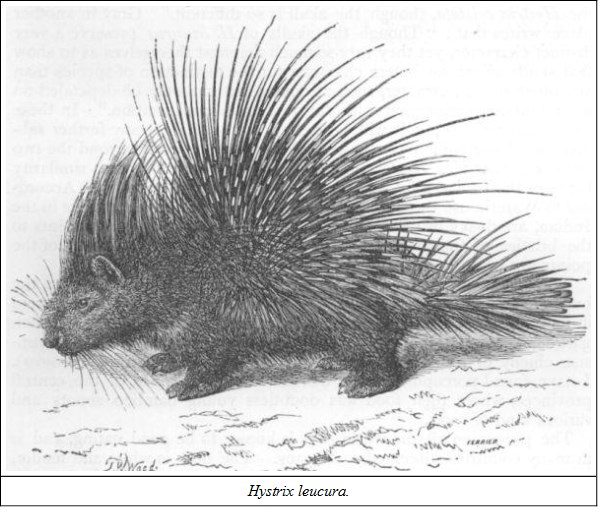

NO. 403. HYSTRIX LEUCURAThe White-tailed Indian Porcupine (Jerdon's No. 204)NATIVE NAMES.—Kanta-sahi, Sayi, Sayal, Sarsel, Hindi; Sajru, Bengali; Chotia-dumsee, Nepali; Saori, Gujrati; Salendra and Sayal, Mahrathi; Yed, Canarese; Ho-igu, Gondi; Phyoo, Burmese; Heetava, Singhalese.

HABITAT.—All over India (except perhaps Lower Bengal), Burmah and Ceylon.

DESCRIPTION.—Blackish-brown; muzzle clad with short, stiff, bristly hairs; whiskers long and black, and a few white spines on the face; spines on the throat short, grooved, some with white setaceous points forming a half-collar; crest of head and neck formed of long black bristles, with here and there one with a long white tip; the spines of the sides are short, flattish, grooved or striated, mostly with white points; the large quills of the back are either entirely black or ringed at the base and middle with white, a few with white tips; the longer and thinner quills on the back and sides have long white terminations; many of these again, particularly the longest, have a basal and one or two central white rings; the short quills on the mesial line of the lumbar region are nearly all white, and the longer striated quills of this region are mostly white; quills of the tail white or yellowish, a few black ones at the root; pedunculated quills are long, broad, and much flattened in old animals.

SIZE.—Head and body, 32 inches; tail, 8 inches.

The description given in his 'Prodromus Faunæ Zeylanicæ' by Dr. Kellaart, who was a most careful observer, has been of great assistance to me in the above, as it was also, I fancy, to Jerdon, and his subsequent remarks are worthy of consideration. "The identification of species from single characters," he observes, "is at all times difficult and unsatisfactory in the genus Hystrix, particularly so as regard the conformation of the skull." And again: "The number of molars varies also in different specimens. In two adults obtained at Trincomalee there were only three molars on each side of the jaw, four being the dental formula of the genus Hystrix."

I think such aberrations ought to warn us from trying to make too many genera out of these animals. Dr. Gray, whose particular forte—or shall I say weakness?—was minute subdivision, classed (in 1847) the Indian porcupines in three sub-families, Hystrix, Acanthion, and Atherura; and Acanthion he some years after (1866, see 'P. Z. S.' p. 308) divided again into three groups, OEdocephalus, Acanthochærus and Acanthion. The difference in the skull of Hystrix and Acanthion lies in the intermaxillaries and the grinders, as follows:—

Hystrix—Inter-max. broad, truncated, wide behind as before; grinders oblong, longer than broad, one fold on the inner, and three or four on the outer side.

Acanthion—Inter-max. triangular, tapering behind; grinders sub-cylindrical, not longer than broad, one fold on the inner, two or three on the outer side.

According to Waterhouse the European porcupine (Hystrix cristata of Linnæus) is the Acanthion Cuvieri of Gray; and Gray, who afterwards modified his views of 1847 in 1866, wrote of it: "I am not aware of any external characters by which this species can be distinguished from the Hystrix cristata, though the skull is so different." Gray in another place writes that: "Though the skulls of H. leucurus preserve a very distinct character, yet they vary so much amongst themselves as to show that skulls afford no better character for the distinction of species than any other single character, such as colour, but can only be depended on when taken in connection with the rest of the organisation." In these circumstances I think it will be better not to attempt any further subdivision of the Indian porcupines in the present work beyond the two already given, viz. Hystrix and Atherura. There is a great similarity between the Indian H. leucura and the European H. cristata. According to Waterhouse the quills in the lumbar region, which are white in the Indian, are dusky in the European, which last has long white points to the bristles of the crest, whereas in the Indian one some only of the points are white, and the rest quite brown.

The Indian porcupine lives in burrows, in banks, hill sides, on the bunds of tanks, and in the sides of rivers and nullahs. It is nocturnal in its habits, and in the vicinity of cultivation does much damage to such garden stuff as consists of tubers or roots. In the jungle its food consists chiefly of roots, especially of some kinds of wild yam (Dioscorea). I have found porcupines in the densest bamboo jungles of the central provinces, where their food was doubtless young bamboo shoots and various kind of roots.

The porcupine all the world over is known to be good eating, and is in many countries esteemed a delicacy. The flesh is white and tender, and is much prized by most people in those places where it abounds. Brigadier-General McMaster, in his 'Notes on Jerdon,' in speaking of the only instance where he found a porcupine on the move after daylight, says: "Just at dawn a porcupine appeared, and, as I suppose his house was somewhere between us, trotted and fed, grunting hog-like, about the little valley at our feet until long after the sun was well up, and until I, despairing of other game, and bearing in mind his delicious flesh (for that of a porcupine is the most delicate I know of), shot him. Well may the flesh be tender and of delicate flavour, for, as many gardeners know to their cost, porcupines are most scrupulously dainty and epicurean as to their diet. A pine-apple is left by them until the very night before it is fit to be cut. Peas, potatoes, onions, &c., are not touched until the owner has made up his mind that they were just ready for the table." The Gonds in Seonee were always on the lookout for a porcupine. I described in my book on that district the digging out of one.

"The entrance of the animal's abode was a hole in a bank at which the dogs were yelping and scratching; but the bipeds had gone more scientifically to work by countermining from above, sinking shafts downwards at various points, till at last they reached his inner chamber, when he scuttled out, and, charging backwards at the dogs with all his spines erected, he soon sent them flying, howling most piteously; but a Gondee axe hurled at his head soon put an end to his career, for a porcupine's skull is particularly tender."

The female produces from two to four young, which are born with their eyes open. Their bodies are covered with short soft spines, which, however, speedily harden. It is said that the young do not remain long with their mother, but I cannot speak to this from personal experience. I have had young ones, but not those born in captivity.

NO. 404. HYSTRIX BENGALENSISThe Bengal Porcupine (Jerdon's No. 205)NATIVE NAME.—Sajaru or Sajru, Bengali.

DESCRIPTION.—"Smaller than the last; crest small and thin; the bristles blackish; body spines much flattened and strongly grooved, terminating in a slight seta Or bristle; slender flexible quills much fewer than in leucura, white, with a narrow black band about the centre; the thick quills basally white, the rest black, mostly with a white tip; a distinct white demi-collar; spines of lumbar region white, as are those of tail and rattle; muzzle less hirsute than in leucura."

SIZE.—Head and body, 28 inches; tail, 8 inches.

There is occasionally a variety to be found of this species with orange-coloured quills, or rather the orange hue is assumed at times. Jerdon mentions the fact that Sclater describes his H. Malabarica as having certain orange-coloured quills in place of white, and also that Blyth considered the two species identical. He also states that Mr. Day procured specimens of the orange porcupine from the Ghâts of Cochin and Travancore, and that they were considered more delicate eating by the native sportsmen, who aver that they can distinguish the two kinds by the smell from their burrows; but he was not apparently aware at the time that a specimen of H. Malabarica with orange quills in the Zoological Gardens in London moulted, and the red quills were replaced by the ordinary black and white ones of the common Indian kind. Dr. Sclater afterwards (see 'P. Z. S.' 1871, p. 234) came to the conclusion that H. Malabarica was synonymous with H. leucura.

NO. 405. HYSTRIX (ACANTHION) LONGICAUDAThe Crestless Porcupine (Jerdon's No. 206)NATIVE NAMES.—Anchotia-sahi or Anchotia-dumsi in Nepal; Sathung, Lepcha; O'—e of the Limbus (Hodgson). (N.B.—The ch must not be pronounced as k, but as ch in church.) Anchotia means crestless, the crested porcupine being called Chotia-dumsi.

HABITAT.—Nepal and Sikim, and on through Burmah to the Malayan peninsula, where it was first discovered.

DESCRIPTION.—Distinguished from the other species "by its inferior size, total absence of crest on its head, neck, and shoulders, by its longer tail, by the white collar of the neck being evanescent; and lastly by the inferior size and smaller quantity of the spines or quills."—Hodgson.

It is covered with black spinous bristles from two to three inches long, shortest on the head and limbs. The large quills of the back and croup are from seven to twelve inches long, mostly with one central black ring.

SIZE.—Head and body, 24 inches; tail, 4, or with the quills, 5½ inches.

This is Hodgson's H. alophus, which is, I think, a more appropriate name than the one given, for its tail is not so very long in proportion. Hodgson says of it: "They breed in spring, and usually produce two young about the time the crops ripen. They are monogamous, the pair dwelling together in burrows of their own formation. Their flesh is delicious, like pork, but much more delicate flavoured, and they are easily tamed so as to breed in confinement. All tribes and classes, even high-caste Hindoos, eat them, and it is deemed lucky to keep one or two alive in stables, where they are encouraged to breed. Royal stables are seldom without at least one of them."

This animal was described by Gray as Acanthion Hodgsonii, the lesser Indian porcupine. Waterhouse, in writing of Hystrix (Acanthion) Javanica, says: "The habits of the animal, as recorded by Müller, do not differ from those of H. Hodgsonii"; and Blyth, as mentioned by Jerdon, was of opinion that the two species were one and the same. The Acanthochærus Grotei, described and figured by Dr. Gray in 1866 ('P. Z. S.' p. 306), is the same as this species. It is to be found at Darjeeling amongst the tea plantations, between 4000 and 5000 feet elevation.

NO. 406. HYSTRIX YUNNANENSISHABITAT.—Burmah, in the Kakhyen hills, at elevations of from 2000 to 4500 feet.

DESCRIPTION.—after Dr. Anderson, who first discovered and named this species: "Dark brown on the head, neck, shoulders, and sides passing into a deep black on the extremities, a very narrow white line passing backwards from behind the angle of the mouth to the shoulder; under surface brownish; the spiny hairs of the anterior part of the trunk flattened, grooved or ungrooved. The crest begins behind the occiput and terminates before the shoulders; the hairs are long, slender and backwardly curved, the generality of them being about 4½ inches long, while the longer hairs measure about six inches.

"They are all paler than the surrounding hairs, and the individual hairs are either broadly tipped with yellowish-white, or they have a broad sub-apical band of that colour. The short, broad, spiny hairs, lying a short way in front of the quills, are yellow at their bases, the remaining portion being deep brown, whereas those more quill-like spiny hairs, immediately before the quills, have both ends yellow tipped.

"The quills are wholly yellow, with the exception of a dark brown, almost black band of variable breadth and position. It is very broad in the shorter quills, and is nearer the free end of the quill than its base, whereas in the long slender quills it is reduced to a narrow mesial band. The stout strong quills rarely exceed six inches in length, whilst the slender quills are one foot long. Posteriorly above the tail and at its sides many of the short quills are pure white. The modified quills on the tail, with dilated barb-like free ends are not numerous, and are also white. There are three kinds of rattle quills, the most numerous measure 0·65 inch in the length of the dilated hollow part, having a maximum breadth of 0·21 inch, whilst there are a few short cups 0·38 inch in length, with a breadth of 0·17 inch, and besides these a very few more elongated and narrow cylinders occur."—'Anat. and Zool. Res.,' p. 332.

SUB-ORDER DUPLICIDENTATA—DOUBLE-TOOTHED RODENTSThese rodents are distinguished by the presence of two small additional incisors behind the upper large ones. At birth there are four such rudimentary incisors, but the outer two are shed, and disappear at a very early age; the remaining two are immediately behind the large middle pair, and their use is doubtful; but, as Dallas remarks, "their presence is however of interest, as indicating the direction in which an alliance with other forms of mammalia more abundantly supplied with teeth is to be sought."

Another distinctive characteristic of this sub-order is the formation of the bony palate, which is narrowed to a mere bridge between the alveolar borders, or portions of the upper jaw in which the grinding teeth are inserted.

The following synopsis of the sub-order is given by Mr. Alston:—

"Incisors 4/2; at birth 6/2; the outer upper incisor soon lost; the next pair very small, placed directly behind the large middle pair; their enamel continuous round the tooth, but much thinner behind; skull with the optic foramina confluent, with no true alisphenoid canal; incisive foramina usually confluent; bony palate reduced to a bridge between the alveolar borders; fibula anchylosed to tibia below, and articulating with the calcaneum; testes permanently external; no vescicular glands. Two families."—'P. Z. S.' 1876, p. 97.

There are only two families each of one existing genus—LEPORIDÆ, genus Lepus, the Hare; and LAGOMYIDÆ, genus Lagomys, the Pika, or Mouse-Hare, as Jerdon calls it. There are three fossil genera in the first family, viz. Palæolagus, a fossil hare found in the Miocene of Dacota and Colorado, Panolax from the Pliocene marls of Santa Fe, and Praotherium from Pennsylvanian bone-caves. A fossil Lagomys, genus Titanomys, is found in the Post-Pliocene deposits in various parts of Europe, chiefly in the south.

FAMILY LEPORIDÆ—THE HARES"Three premolars above and two below; molars rootless, with transverse enamel folds dividing them into lobes; skull compressed; frontals with large wing-shaped post-orbital processes; facial portion of maxillaries minutely reticulated; basisphenoid with a median perforation, and separated by a fissure from the vomer; coronoid process represented by a thin ridge of bone; clavicles imperfect; ears and hind-limbs elongated, tail short, bushy, recurved."—Alston.

Hares are found all over the world except in Australasia. The Rabbit is much more localised; in India we have none, unless the Hispid Hare, the black rabbit of Dacca sportsmen, is a true rabbit; it is said to burrow, but whether it is gregarious I know not. Another point would also decide the question, viz. are the young born with eyes open or shut? The hare pairs at about a year old, and has several broods a year of from two to five; the young are born covered with hair and their eyes open, whereas young rabbits are born blind and naked. The hare lives in the open, and its lair or "form" is merely a slight depression in some secluded spot. It has been noticed that the hare always returns to its form, no matter to what distance it may have wandered or have been driven.

GENUS LEPUSNO. 407. LEPUS RUFICAUDATUSThe Common Indian Red-tailed Hare (Jerdon's No. 207)NATIVE NAMES.—Khargosh, Kharra, Hindi; Sasru, Bengali; Mullol, Gondi.

HABITAT.—India generally.

DESCRIPTION.—"General hue rufescent, mixed with blackish on the back and head; ears brownish anteriorly, white at the base, and the tip brown; neck, breast, flanks and limbs more or less dark sandy rufescent, unmottled; nape pale sandy rufescent; tail rufous above, white beneath; upper lip small; eye-mark, chin, throat, and lower parts pure white."—Jerdon.

SIZE.—Head and body, 20 inches; tail, with hair, 4 inches; ear externally about 5 inches; maximum weight, about 5 lbs.

The Indian hare is generally found in open bush country, often on the banks of rivers, at least as far as my experience goes in the Central Provinces. Jerdon says, and McMaster corroborates his statement, that this species, as well as the next, take readily to earth when pursued, and seem to be well acquainted with all the fox-holes in their neighbourhood, and McMaster adds that they seem to be well aware which holes have foxes or not, and never go into a tenanted one.

The Indian hare is by no means so good for the table as the European one, being dry and tasteless, and hardly worth cooking.

NO. 408. LEPUS NIGRICOLLISThe Black-naped Hare (Jerdon's No. 208)NATIVE NAMES.—Khargosh, Hindi; Malla, Canarese; Sassa, Mahrathi; Musal, Tamil; Kundali, Telegu; Haba, Singhalese.

HABITAT.—Southern India and Ceylon; stated to be found also in Sind and the Punjab.

DESCRIPTION.—"Upper part rufescent yellow, mottled with black; single hairs annulated yellow and black; chin, abdomen, and inside of hind-limbs downy white; a black velvety spot on the occiput and upper part of neck extending to near the shoulders; the spot under the neck is in some specimens of a bright yellow colour; ears long, greyish-brown, internally with white fringes, at the apical part dusky, posteriorly black at the base; feet yellowish; tail above grizzled with black and yellow, beneath white."—Kellaart.

SIZE.—Head and body, 19 inches; tail, 2½ inches; ears, 4¾ inches.

A friend of Brigadier-General McMaster's, writing to him, says: "The black-naped hare of the Neilgherries, which appears to be the same as that of the plains, only larger from the effect of climate, often, when chased by dogs, runs into holes and hollow trees. I have found some of the Neilgherry hares to be nearly, if not quite, equal to the English hares in flavour. I think a great deal depends upon keeping and cooking."

NO. 409. LEPUS PEGUENSISThe Pegu HareNATIVE NAME.—Yung, Arakanese.

HABITAT.—Pegu, Burmah.

DESCRIPTION.—Very like L. ruficaudatus, but with the tail black above; the colour of the upper parts is separated more distinctly from the pure white of the under parts.

SIZE.—Head and body, about 20 inches.

NO. 410. LEPUS HYPSIBIUSThe Mountain HareHABITAT.—Northern Ladakh.

DESCRIPTION.—Colour rufous brown, more or less mixed with black on the back, dusky ashy on the rump; lower parts white with a slight rufescent tinge, fur long, woolly, rather curly, and thick; head brown, whitish round the eyes; whiskers partly black, partly white; outside surface of ears brown in front, whitish behind, the brown hairs having short black tips; the extreme tip of ears black; tail white; throughout limbs chiefly white, a brownish band running down the anterior portion of the fore-legs.

SIZE.—Of skin about 24 inches. (See Blanford's 'Second Yarkand Mission,' p. 60; also plate iii.)

NO. 411. LEPUS PALLIPESThe Pale-footed HareNATIVE NAMES.—Togh, Toshkhen, Yarkandi, i.e. Mountain Hare.

HABITAT.—Yarkand; Thibet.

DESCRIPTION.—"Fur long, dense and soft, of a pale ochre colour, but on the back of the animal pencilled with black; haunches greyish; under-parts white, chest of a delicate yellow rufous tint; the front of the fore-legs and the fore-feet nearly of the same hue; tarsus almost white, but somewhat suffused with rufous in front; tail white, excepting along the middle portion of the upper surface, where it is grey."—Waterhouse's 'Mammalia,' vol. ii. p. 62.