полная версия

полная версияConstantinople and the Scenery of the Seven Churches of Asia Minor

There is something in every form of Turkish sepulture, strikingly adapted to the end proposed, and displaying a strong contrast with our own. Death, without being divested of its solemnity, is disarmed of everything that could disgust and repel. The dark and pensive cypress groves, with their evergreen foliage and aromatic resinous exudation−the friend seen watering the flowers, or feeding the singing birds, which are supposed to gratify the dear object that lies below−exhibit spectacles far more interesting and affecting than the foul and mouldering heaps, and disgusting dilapidations of our dismal church-yards; while the Imperial Turbés, where every thing is simply neat and soberly decorated, are very different indeed from the dark and noisome cells of our regal monuments.

SPRING OF THE MIRACULOUS FISHES AT BALOUKLI.

NEAR CONSTANTINOPLE

T. Allom. J. Tingle.

Of all the “Ayasmata,” or Holy Wells, in the vicinity of Constantinople, this is held in highest estimation by the Greeks, whose faith in its efficacy seems daily to increase. Many poets have devoted their gift of verse to its celebration; but two are more eminently distinguished. Nicephorus the most Beautiful, called, from his mellifluous song, the “Attic Bee;” and Johannes with the flowing hair, who acquired for himself the name of the “Sweet-voiced Grasshopper.” The former thus eulogizes the health-giving spring.

The stricken rock sent forth the bubbling tide:That rock was Christ, the sacred bards declare−The perishable nature never died,Which drank its rill.−But, lo! faint mortal, whereAnother fount his pitying mother gives.Approach−the dying man who drinks it lives.This invitation was obeyed, and crowds rushed to drink the gifted waters. The 29th of April was appointed, in the Greek church, for the celebration of a festival in honour of the Spring, and the day always displayed an extraordinary spectacle of Greek credulity and enthusiasm. During the disturbance of the insurrection, this ceremony had been suspended. Those who attempted to celebrate it were attacked by the Turks, who assaulted and dispersed the crowds, and the sacred fount was approached only secretly and occasionally by individuals. But when tranquillity was restored, and the Greeks were again allowed to resume the celebration of their religious rites, the multitude thronging to this place on the appointed festival was astonishing. A traveller who was induced to witness it, even before the church was rebuilt, passed with a whole fleet of caïques from Pera and Constantinople, to the nearest landing-place on the Sea of Marmora. From thence there was a constant current of people ascending through the city to the Selyvria gate, and on issuing from that, he found the whole plain densely crowded for several miles with a concourse of Turks as well as Christians; it resembled an English fair, where refreshments were sold, trinkets and wares exhibited, and all sorts of amusements practised. Bulgarian minstrels, the constant attendants on such meetings, walked pompously about, blowing their enormous bagpipes; crowds of Greeks, holding white handkerchiefs so as to form a long chain, went through all the mazes of the romaika, while a vast number of Turkish females, shrinking from such a display of themselves, sat decorously and quietly on the elevated banks, in various groups, passing from mouth to mouth the tube of one long chibouque, or nargillai, while the bowl or vase remained fixed in the centre, and the mouth-piece went round the circle. Though more passive in their admiration, they seemed no less interested in the object of the festival.

But the crowds congregated about the sacred well were far more seriously engaged: various “impotent folk, of blind, halt, and withered,” were placed near the waters, like those of the pool of Bethesda, brought there to be healed. They lay stretched on carpets or blankets, on which all the pious who passed, threw money, till the patient and his bed were spangled over with paras. In different parts of the ruined edifice were priests in their richest vestments, who displayed the most celebrated and wonder-working relics of their church on shrines erected for the purpose, and supported, in both their hands, capacious silver dishes, which were filled with the contributions of the crowd. But the ardour and enthusiasm of the devotees who repaired to the well for health exceeded all belief. Priests stood around the Spring with pitchers in their hands, which they constantly filled, and handed up to those about them. They were eagerly seized by every person who could catch them, and poured with trembling emotion on their heads and breasts, where they were rubbed, so that every particle of the health-giving fluid might be imbibed by the pores of the skin; while those who could not pay for, and were not favoured with this precious ablution eagerly caught at the stray drops with their hands, and applied them reverently to their faces and bosoms. Occasionally, a frighted fish darted across the bottom of the well; and when a glance of this fried phenomenon was caught by the crowd, a shout of exultation was raised, followed by a low murmur of praise and thanksgiving for the miracle.

When the church was re-edified, the Spring was also repaired, and the annual ceremony was observed with equal enthusiasm, but somewhat more decorum, in the regular edifice, than among the dilapidated ruins. The chancel of the church, as the most sacred part, was built directly over the well, and from thence there is a descent by a flight of stone steps. This terminates in a vaulted apartment, ornamented with niches surmounted by handsome pediments, which resemble the porches beside the pool of Bethesda; and in the centre is a square enclosure, surrounded by a marble parapet, within which the sacred Spring now bubbles up. Behind it, under an arcade supported by marble pillars, is the shrine of the panaya, by whose bounty the waters were endued with their inestimable virtues, lighted by a perpetual lamp. On the occasion of the grand festival, the vault is illuminated by the enormous chandelier which is seen on one side.

Our Illustration presents the characteristic features of this abiding superstition of the modern Greeks. Down the steps are seen descending the devout to this pool of Bethesda who expect to see the miraculous fishes, like the angel, “trouble the waters”, and then to partake of its healing qualities. Within the enclosure of the well are men eagerly imbibing the precious fluid; and on each side are papas in their robes, strengthening the faith of the pious, and receiving the price of the miraculous waters.

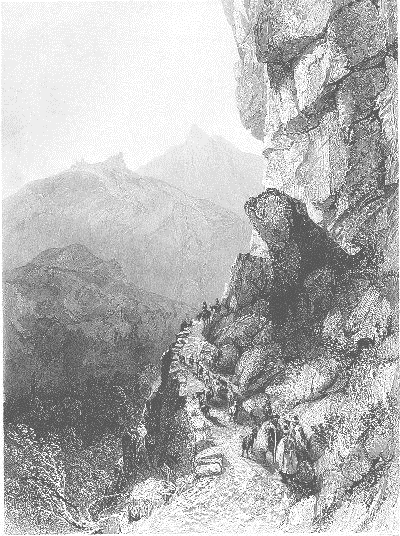

ASCENT OF THE HIGH BALKAN MOUNTAINS.

ROUMELIA

T. Allom. Drawn from Nature by F. Hervé, Esq. W. Floyd.

Among the many wild and stupendous objects presented by the different passes through this magnificent chain, those by Tornova are, perhaps, the most striking. Tornova is the seat of a bishop of the Greek church, rendered particularly interesting to the people of England by the conduct and character of its present prelate, the learned Hilarion. When the British and Foreign Bible Society proposed to place the word of God within the compass of every man’s understanding, by translating it from the dead language in which it was written, and presented it to him in his vernacular tongue, some of the prelates of the Greek church, like those of the Latin, were opposed to the measure; but the late excellent patriarch, Gregory, who fell a victim to Turkish cruelty at the commencement of the revolution, was too pious and too enlightened to sanction such a sinful exclusion. He therefore gave his free consent to have the Scriptures rendered into modern Greek for the use of the laity of his flock, and it was assigned for that purpose to Hilarion, one of his clergy distinguished for his learning and piety. The circumstance caused no small degree of excitement in the Greek church. The great majority who favoured the measure were ardent in their wishes and zealous in their endeavours for its speedy accomplishment. The indefatigable Hilarion proceeded with his pious task, which was to effect the same reformation in the Greek as it had in the Latin church. It was actually put to press in the printing establishment of the patriarchate, and the first sheet of the precious work thrown off, when the Turks, excited, it is suspected, by the enemies of the measure, rushed in with axes and other implements, broke in pieces the cases, scattered the types abroad, and cast the first impressions of the Gospel into the court-yard and tank of water, where they were trampled on, torn, and sunk, till the whole of the printed sheets were destroyed, with other literary matter found in the printing-office. This event suspended the work, and the unsettled and disturbed state which followed prevented its resumption. The good and enlightened patriarch and his chaplains, who had laboured to promote the undertaking, were dead, the greater part of his clergy were in exile or in prison, while the learned Hilarion, having escaped the first burst of persecution, was, by one of the sudden vicissitudes so common in the East, dragged from his obscurity, and elevated to the see of Tornova, and, on the summit of the lofty Balkans, completed that sacred work which is to enlighten the world below.

The town of Tornova, besides being the largest in the region of the Balkans, is the only one built on the elevated central ridge from the Euxine to the Adriatic. Its site is very singular; it is seen from below, “hanging, like a swallow’s nest,” from the stupendous craigs above. When the traveller climbs to these upper regions, he walks through streets running on ridgy terraces, and looks down from a dizzy height on the road far beneath, which is at length lost to his sight in a deep abyss. A singular effect is observed in these regions, similar to that which occurs between the tropics. The setting sun is succeeded by no crepuscular illumination, and the eye is not accustomed to the gradual decrease of light: sunset seems to extinguish all atmospheric reflection, and darkness suddenly envelopes the horizon long before it is expected. Thus it happens that travellers are frequently surprised in the most dangerous and difficult part of the precipitous road, and compelled to halt on some projecting rock, till day-dawn extricates them from the perilous position in which night had unexpectedly overtaken them. To guard against this, paper lanterns are sometimes provided. The paper of which they are made is compressed into a small flat circular surface, and carried easily inside the hat or turban. When used, they are drawn out into a cylinder, and a taper placed inside, and, by the help of this faint and uncertain light, tied to the end of a pole and hung over the edge of the precipice, the adventurous traveller cautiously creeps along, rather than remain all night exposed on a naked craig to the inclemency of a mountain-region.−Among the phenomena of these mountains are certain visionary figures, which have something awful and supernatural in their aspect. Dense forms of gigantic beings, resembling those observed on the Hartz, are seen suddenly to issue out of chasms or forests, and move along like dim and undefined spectres through inaccessible places, where no mortal or embodied existence could possibly find a footing. These are columns of mist, sometimes so numerous and frequent as to seem like companies of giants travelling through the mountain-passes. The janissary or surrogee, who accompanies the traveller, is struck with awe, and exclaims “Allah keerim,” (God is merciful,) bows his head, and repeats his namaz as the spectres pass. It not unfrequently happens that sudden bursts of wind follow these appearances, tearing up trees, and sweeping through valleys with dangerous violence. As the misty columns are often the precursors of these storms, they are supposed to be their cause; they are, therefore, ascribed to the malignity of these visionary giants, who blow them forth over the unfortunate traveller, as the breath of their nostril.

Sometimes the traveller is surprised by sudden light gleaming from the rocks around him, and the roar of fires bursting from caverns. These, however, arise from a more explicable cause. The iron-ore with which the interior of the mountains abounds, is generally smelted on the spot. The red flame is then seen issuing from the riven rock, the blows of sledges echo through the caverns, and the dark and grim visage of the workmen are visibly illumined by the blaze. These appearances at night, in the deep solitude of the mountains, are very striking, and strongly remind the traveller of Vulcan’s forge in Etna, and his Cyclops fashioning thunderbolts. When a commotion of the elements supervenes, as frequently happens in these elevated regions, when the air is rent and the rocks around are shattered by the electric fluid, it requires no great stretch of the imagination to fancy it is the fabricated bolts of these grim artisans, that have now, as in the days of the poets, caused the destruction.

Our illustration presents one of those rugged ascents, suspended as it were over the perpendicular flank of a mountain-wall, on one side bounded by a deep chasm, and on the other overhung by a lofty precipice. This path is sometimes not more than a yard in breadth, and does not allow loaded horses space to pass each other. When this occurs, there is a mortal contest for the inside, and one pushes the other into the gulf below. Sometimes the path turns round a short angle, and when the traveller has accomplished the passage of the perilous point, he sees just before him a dark and dismal chasm, over which his horse’s neck projects, and his next step would precipitate him. His feeling of insecurity is increased by the state of the animal he rides. Instead of being shod with rough and pointed irons, which would give a firmer footing in ascending and descending such declivities, the shoe is a flat circular piece of smooth metal, perforated by a single opening in the centre, and affording not the slightest hold on what it presses. Hence, in going down, the motion of the animal is sliding, and the rider with horror sees the beast, to which he trusts his life, every moment ready to shoot over the edge of the narrow road, without a possibility of stopping or restraining itself. Yet such is the sure-footed sagacity of these mountain-steeds, that accidents rarely occur, and they glide down for several hundred yards, through a steep and tortuous descent, dexterously turning round every projecting rock before them, which seems to stand in the way for the express purpose of pushing him over the edge.

CIRCASSIAN SLAVES IN THE INTERIOR OF A HAREM.

CONSTANTINOPLE

T. Allom. H. Mote.

The country now called Circassia was part of that undefined region formerly denominated Colchis, between the Euxine, the Palus Mæotis, the Caspian sea, and the Caucasus. It was this region whence the Greeks brought their first golden freight, of which a woman formed the most valuable part. From that time to the present day there has been constant importations of females. These countrywomen of Medea retain that beauty of person and ferocity of character of their eminent predecessor, as also, it is said, her knowledge of noxious herbs, which abound to this day, as formerly, in their country, and which they apply not to prolong but to abridge the term of human life, whenever their interests or their passions demand the sacrifice of their rivals.

Circassia was formerly governed by its own wild but independent sovereigns; it is now almost all absorbed in the vast territories of Russia; the people have but little advanced in civilization since Jason first visited their shores; their habits are, as they have always been, predatory and unsettled; they are a nation of robbers and man-stealers, who trade in slaves, and add their own children, whom they bring up to sell. Like all barbarous people, they are divided into tribes; the eldest of each becomes the leader, but he is not allowed to possess any property except his horses and arms, and such tribute as he can exact from his neighbours. Their element is war, during which only they have authority. When it is at an end, they merge into obscurity, their dress, food, and habitations being no way distinguished from those of the common people.

Next to these are the Usdens, who are the landholders and lawgivers of the community, and who alone display what little of civilization exists among them. They govern by no written law, but certain hereditary usages, which are varied as the caprice or will of the Usden determines; the great body of the people are vassals or slaves. Their manufactures are rude and scanty, and their tillage insufficient to supply their own wants. They have no written language, and no circulating medium of coin; all their knowledge, then, is confined to traditionary fables, and all their commerce to exchange and barter. The only commodities in which they can trade are two−horses, and human beings. The former are well trained in all the discipline and instruction necessary for their state, and a Circassian horse is a well educated and accomplished animal; the latter are totally neglected, and, however attractive by personal comeliness, are altogether ignorant, and seem to have no capability beyond the instinct of nature.

When females are not sold, but remain at home, and are married, they reside in huts distinct from their husbands, and bring up a brood of children in no respects superior to themselves. Their whole energies are exerted to stimulate the predatory habits of their husbands, and their greatest gratification is in the plunder they are able to bring home. They seem to have no ties of kindred, no domestic affections, no family attachments; the daughter, if she is found to have any personal attractions, is educated solely on the speculation of selling her to advantage, and she frequently demands it from her parents as a right to which she is entitled. From this cause it is that all kindly feelings are obliterated, all love for others extinguished, and all passion is centred in self. Christian missionaries early penetrated into this region, and converted the people to their faith, and subsequently the followers of Mahomet entered it, and divided them between the Koran and the Gospel; but they now seem to have little knowledge of either. A nominal Moslem parent brings up her daughter in the seeming profession of that faith, that it may recommend her to her future master at Constantinople; a nominal Christian educates her child in no religion at all, that there may be no impediment to her conforming to any other; thus her natural passions are freed from all the restraints that religion would impose on them. From these causes it is, that there is a certain ferocity and irreclaimable wildness observable in a Circassian beauty. She gratifies the sensuality, but never secures the esteem, of him to whom she is afterwards consigned. She is an object of desire, but never of regard, and always excites more fear than love.

When a vessel arrives on the coast, it is always for the purpose of traffic in slaves; and all the girls, who have been waiting its approach with longing eyes, prepare themselves to be sold to the best advantage, and their hearts bound with the bright prospect which they are taught to believe lies before them. The splendour of the harem is contrasted with their own miserable huts; the rich stuffs in which they are to be clothed, with their homely, coarse, and squalid garments; the generous viands on which they are to be fed, with the meagre of their scanty diet. They have no ties to attach them to their native land, or dim the bright prospect that awaits them in another. They look upon their sale to a foreign merchant to be the foundation of their future fortune, and their entrance into a foreign ship their first step to a life of pleasure and enjoyment; nor are they disappointed even in the outset.

These Oriental slaves are conveyed, not in the coarse and brutal manner in which European traders carry on their traffic in human flesh. The vessels sent to bring them to their capital are well appointed in every respect for their accommodation. As the price is to depend on the state of health and beauty in which they arrive, every precaution is taken to preserve them. Instead of being crammed into noisome and suffocating holds, the greatest attention is paid to their comforts; their appetites are consulted, their pleasures are complied with, so that neither privation nor anxiety may impair their looks; and the slave dictates to her owner, in whatever she wants or wishes. When arrived, they are lodged in a spacious khan provided for them, and the police are especially ordered that every thing shall be cared for.

Now comes the Kislar Aga, or chief of the black eunuchs, to select for the imperial harem the most lovely and desirable of the importation, and having conducted them to his master, they are assigned apartments in the seraglio, and placed under the care of the instructress of the females. The rest are sent to the Aurut Bazaar, to be sold to those who have the means to purchase them. The Africans, and slaves of other countries, are here exposed, but the Circassian is secluded from the general crowd in separate apartments, which are carefully closed against all intruders, except on days of sale, when the sacred rooms are thrown open from nine in the morning till midday; and every true believer comes to avail himself of the permission of the Koran, and make new selections for the enjoyments of his harem. An infidel is inhibited from entering the market, unless by special permission; and so far from being allowed to purchase, he is not even permitted to look on those chosen females, lest the glance of his evil eye might wither the expected enjoyment of the faithful purchaser.

As these females receive no education at home, it sometimes happens that the Jew slave-merchant who buys them, endeavours to bestow on them such accomplishments as may enhance their value. These, however, are generally fruitless efforts. Personal, not mental qualities, are those that are sought for, and most prized. The Circassian seems to have an inaptitude for any improvement of the mind; and while the Greek or French females, whom the fortune of war or other calamity has consigned to slavery, make considerable progress under their instructors, the indolent and voluptuous Circassian despises such vain labours, and few attain even the elementary accomplishment of reading or writing. Music, such as it is, is most frequently attempted, because it is an enjoyment of the sense, and acquired without mental labour.

Our illustration represents the master of the harem indulging in his favourite recreation. His nargillai, scented with fragrant pastils, fills the small apartment with its drowsy vapours. Reclining on his cushioned carpet, he contemplates the languid, sensual features of his Circassians placed on the divan beside him, who try to amuse him with the only accomplishment they are capable of attaining, or he of feeling or comprehending. Next the door stands the black eunuch, guarding with jealous and malignant eye the entrance into this sacred seclusion.

CONSTANTINOPLE, FROM CASSIM PASHA

T. Allom. J. C. Armitage.

From the summit of the hill of Pera, called from its elevation Tepe Bashi, or “the head of the hill,” the ground slopes to the Golden Horn, displaying an exceedingly diversified and picturesque surface, comprehending not only the beautiful cemetery, and the city of Constantinople, but also the suburbs of Cassim Pasha and Piri Pasha, both connected with many important and interesting events. The view is so attractive, that the Tepe Bashi forms the great promenade of Pera. It is every evening crowded with the elite of the Frank society of the capital, mixed with distinguished natives. Ambassadors, attachées, dragomans, hakims, merchants of all nations, in their respective costumes, here assemble, and form a moving picture of a very gay and varied aspect.