полная версия

полная версияConstantinople and the Scenery of the Seven Churches of Asia Minor

But the most desperate and extraordinary of this cavalry, are the Delhi, or Deliler, which literally means “madmen,” a name their conduct well entitles them to bear. They are generally recruited from Servia and Croatia, and are of robust stature, and fierce and formidable aspect. This they endeavour to increase by their dress: their helmets are formed of a leopard’s head and jaws, with the skin hanging down to their shoulders; and this is surmounted by the beak, wings, and tail of an eagle, united with threads of iron. Their vests are skins of lions, and their trousers the hides of bears with the shaggy hair outside. They despise the crooked sabre of the Spahi, but carry a target and a serrated lance of great weight and size. These men rush on their enemies with the most reckless impetuosity; and, should any of them hesitate at the most hopeless and desperate attack, they are dishonoured for ever.

All these are perhaps the best mountain-horsemen in the world, though nothing can be more unfavourable to their firm seat and rapid evolutions than their whole equipment. Their saddles are heavy masses of wood, like pack-saddles, peaked before and behind, and seem to be the most awkward and uneasy in the way they use them. Their stirrups are very short, and their stirrup-irons very cumbrous, resembling the blades of fire-shovels, the angles of which they use to goad on the horse, as they have no spurs. This heavy and awkward apparatus is not secured on the horse by regular girths, but tied with thongs of leather, which are continually breaking and out of order. On this insecure seat the rider sits tottering, with his knees approaching to his chin; yet there never were more bold and dexterous horsemen, in the most difficult and dangerous places. When trooped together they observe little order, yet they act in concert with surprising regularity and effect, particularly on broken ground and mountain-passes, seemingly impracticable to European cavalry. They drive at full speed through beds of torrents, and up and down steep acclivities, and suddenly appear on the flanks or rear of their enemies, after passing rapidly through places where it was supposed impossible for a horseman to move.

Such had been the general character of Turkish cavalry, but the Sultan, in his military reforms, obliterated the characteristic distinction of each corps, and amalgamated them all to an uniformity of European discipline. He one day saw a restive horse baffle all the attempts of his rider to reduce him to obedience, and finally throw him to the ground. There happened to be standing near, an Italian adventurer, named Calosso, who had come to Constantinople in search of fortune, with many of his countrymen. He seized the unruly animal by the bridle, disencumbered him of his awkward ponderous saddle, mounted him bare-backed, and presently reclaimed him to a state of perfect discipline. His dexterity attracted the notice of the sovereign, who at once availed himself of his abilities. He first put himself under his care, and learned the art of European manège, at considerable personal risk. He cast away the wooden pack-saddle, and set his cavalry an example by mounting himself on a bare-backed horse. The sudden transition from a lofty seat, where the limbs were confined and fixed to the horse by a wooden frame, and the legs supported by firm pressure on a broad stirrup, to the sharp spine of a beast without either saddle or stirrup, was scarcely tolerable; and the imperial recruit would have been often precipitated to the ground, but for the aid of his Italian instructor, who was always at hand to support him. Yet he persevered with his usual determination, and he became in a short time an accomplished European horseman, and induced his subjects to follow his example. There was no European usage which a Turk found it more difficult to adopt than this. A short stirrup was congenial, and in keeping with all his other habits. When he sat, his legs were not properly pendent, but turned, as it were, under him, and he preserved on his pack-saddle nearly the same position as he occupied at ease on his divan. His first sensations, therefore, in his new position, with his legs stretched down, were those of discomfort and insecurity; and the first training of a squadron of Turkish cavalry, was one of the most difficult reforms the Sultan had to encounter.

Our illustration presents the magnificent barracks built for the cavalry on the shores of the Bosphorus. Kislas, or “barracks,” are among the largest and most striking edifices seen round Constantinople. The first object seen on approaching the Bosphorus is the vast barrack at Scutari; and on the opposite hill, over the hanging grounds, at Dolma Baktche an equally large one. A splendid edifice of this kind existed at Levend Chiflik; but in the sanguinary conflict which took place between the military on the establishing of the Nizam Djeddit, or “new corps,” this noble edifice, with others, was razed to the ground. But of all the barracks round the city, that erected for the cavalry is the most decorated, and forms one of the most striking objects which ornament the lovely Bosphorus.

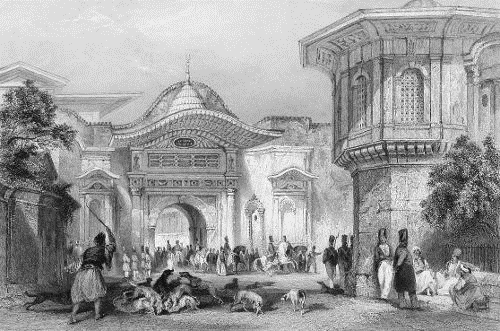

ENTRANCE TO THE DIVAN, CONSTANTINOPLE

T. Allom. F. W. Topham.

The Divan is not only a court of justice, but of legislature and diplomacy. It is here that laws are made, suits decided, firmans issued, troops paid, and the representatives of sovereigns made fit to be introduced to the august presence of the Sultan.

The chamber where all those affairs are transacted is a room in a small detached edifice surmounted by two domes, in the interior court of the seraglio. It is quite naked, with no furniture but a wooden bench running along the wall, about two or three feet high, covered with cushions. This long and fixed sofa is the furniture of every house. It is called a Divan, and gives its name peculiarly to this apartment. This chamber has no doors to shut at the entrance, for, as it is a court of justice, it is supposed to be always open, inviting all the world to enter it, and never to be closed against any suitor. Opposite the entrance is a moulding forming an arcade, round the summit of which is written in letters of gold, a confession of faith from the Koran, and beneath it is the seat of the judges. On the wall on the south is represented the form of an altar, to which suitors in any cause turn themselves, and, on a signal given by the crier, address prayers for the success of their suit, as to the Al-Caaba at Mecca. The grand vizir is obliged to administer justice in this hall four times a week−Mondays, Wednesdays, Fridays, and Saturdays.

As the Koran is the repository of the civil as well as the religious code of the empire, all suits are decided here by its authority. Attached to most mosques, are medresis or “colleges,” where students are instructed in law as well as divinity, by muderis or “professors.” When qualified by a certain course of study, they are despatched to the towns and villages in every part of the empire, where they become the mollas, naibs, and cadis, or various “judges,” appointed to dispense justice, founding all their decrees on the precepts of the Koran. Of these there are two considered as superiors, and named Cadileskers, one for the northern portions of the empire, called Roumeli Cadilesker, or “the supreme judge of Europe;” the other for the southern, called Anadoli Cadilesker, or “the supreme judge of Asia.” A third, who decides in ecclesiastical matters only, is called Istambol Effendi, or “judge of the capital.” These, particularly the two former, are always the assessors of the grand vizir in the Divan, and form with him the grand tribunal of the empire. From the earliest period of Oriental usage, the right hand has been deemed the post of honour, but the thing is reversed in matters connected with the law. The Turks are particularly tenacious of position as indicating distinction. The Cadilesker Anadoli sits on his left hand, and the Cadilesker Roumeli on his right, and the same precedence is rigidly observed among the suitors of the court. The judges, when constituting this tribunal, do not sit with their legs folded under them, as is the universal practice of all Orientals, but their legs are suffered to hang down and rest on a footstool, and it is thus the sultan himself receives the ambassadors of foreign powers. It is a deviation from the ordinary position, which is supposed to confer seriousness and dignity on any important occasion.

When a Turk goes to law, he first proceeds to an arzuhalgee; this is a kind of attorney, or licensed scrivener, who holds an office in various parts of the city, and who alone is permitted to undertake a statement of a case. So tenacious of this privilege is the arzuhalgee, that no officer of state, however competent his ability or high his station, can draw up a process for himself, but must apply to this scrivener. To him the plaintiff goes, and he draws up for him an arzuhal, which is not a detail of lengthened repetitions, but literally a brief, containing a statement of the case in a few words. With this he proceeds early in the morning to the Divan, on one of the appointed days of session, and he is ranged with other suitors in two long lines, awaiting for sunrise, when the grand vizir attends to open the court. On his arrival, he passes up the lane formed by the suitors, and, having arrived at the Divan, a small table covered with a cloth of gold is laid before him, and the court opens. The first suitor on the left has the precedence. He presents his arzuhal to a chaoush or officer in attendance, who hands it to the chaoush bashee, and by him it is laid before the buyuk teskiergee, or “great receiver of memorials,” who stands on the left hand of the grand vizir. He reads out the plaintiff’s case with a loud voice, and the defendant is called on for a reply. Here is none of the tedious formulas of European pleaders, no exhibitions of forensic eloquence, none of “the law’s delay.” Should it appear that any attempt was made to entangle the subject in legal quibbles, or lengthen it unnecessarily, so that justice maybe either defeated or deferred, the parties are liable to be bastinadoed on the spot, at the discretion of the judge.

Two witnesses are required to establish a fact, and never more. If it be a case of debt, the simple promise of the debtor is sufficient, either written and marked with his seal, or, if verbal, attested by witnesses. The parties generally plead their own cause; the judges, without reference to any code but the Koran, consider the simple facts. Having decided, they give sentence, which is submitted to the grand vizir; and, if it coincide with his own opinion, which is generally the case, he writes at the bottom of the arzuhal the word Sah, “surely.” If, on the contrary, he dissents, he writes his own decree, and the parties are dismissed with a hujet, or “sentence of the grand vizir,” which is final. It is on these occasions only, that disputation takes place in a Turkish court of justice; for if the cadileskers are supposed capable, either through ignorance or design, of pronouncing an unjust decree, they are degraded, and never suffered again to hold any place of trust. They, therefore, defend their opinions with obstinacy, and the court resounds, not with the pleadings of lawyers, but the disputation of the judges. Proceeding thus from left to right, the cases are summarily decided till it is dark, or they are all disposed of; and as justice may not be deferred by the intervention of any avoidable delay, the members of the court dine where they sit. A frugal meal is brought in at midday and despatched in a few minutes.

Such is the process when the Divan is a court of justice; but when it becomes a Galibé Divan, or “council chamber,” all the affairs of state become objects of its deliberation or discussion. This is held on Sundays and Mondays. Here the grand vizir and cadileskers also sit, assisted by the reis effendi, or “minister for foreign affairs,” the mufti, or “chief of ecclesiastical affairs,” and the agas, “or heads of the military departments.” When the first dawn of European light opened upon Turkey, this council of despotism made some approximation to a popular representation. In the difficulties that surrounded the state at the commencement of the Greek revolution, the embarrassed but enlightened Sultan invited the mutelins or “paymasters” of the different Janissary corps, and also deputies from the esnaffs or “corporations” of trades, to become members, and, as these were taken from the respectable class of citizens, they were fair representatives of their opinions to a certain extent, and so formed the first Turkish parliament.

The Sultan introduced another innovation also into the mysterious proceedings of the Divan. It was not usual for the sovereign to appear personally there, but whenever an affair was discussed, the grand vizir appeared before him, with the members of the council, in an apartment of the seraglio, and there took his directions. But, though he was seemingly absent, it was known that he was always present on any affair of importance. There stands at the back of the Divan, some distance above the heads of those who sit on it, a projection like a bow-window from the wall. This is covered with gilded lattice-work, and concealed by curtains drawn behind. It is called the Sha Nichin or “sultan’s seat,” and here he ensconced himself, and heard and saw whatever was going on below. As the curtain was usually drawn, it was not known to a certainty when he was there or not, but he was dreaded like the tyrant of Syracuse, as always listening, and sometimes detected by the angry gleam of an eye glancing through the lattice, and denouncing vengeance on some obnoxious member of the council. It is for this reason called “the dangerous window,” and looked up to with awe and terror from below. Many anecdotes are told of this Sha Nichin. Achmet I. who is said to be its inventor, constantly watched the proceedings of the Divan from hence, when it was supposed he was buried in sensual indulgences in the remote recesses of the seraglio. One day, when a court of justice was held, a soldier presented an arzuhal to the grand vizir, and, supposing it was treated with neglect, and himself with injustice, he drew his yatagan, and suddenly plunged it into his body. The chaoushs and others cast themselves upon the assassin, and were about to cut him to pieces, when the curtain of the Sha Nichin was drawn aside, and the voice of the Sultan was heard like thunder issuing from it. He commanded them to desist, and, stepping down, he himself examined the man’s case, with the bleeding body of the grand vizir on the Divan beside him. He thought he had reason to suppose the sentence was unjust, and the delinquent had provocation; so he dismissed the soldier as an injured man, and caused the body of the grand vizir to be cast into the sea as an unjust judge.

Another use of the Divan is, that it is the place where the troops, particularly the janissaries, received their pay. On these occasions men bring in small leathern bags of piasters, which they pile on the floor, till they form heaps three or four feet high, and ten or twelve long. When these are all laid, and the whole amount of pay ready, the grand vizir sends a sealed paper to the Sultan, notifying that large sums of money are lying before him on the ground, and humbly entreating to know what it is his pleasure to do with it. The chaoush returns after some delay, with an iron-shod pole, which he strikes loudly on the pavement, to announce his approach with the answer to the important question, and presents a huge packet to the vizir, which he receives with profound reverence, first pressing it to his forehead and then to his lips. Having read the communication, he announces aloud, that it is the Sultan’s pleasure that all the heaps of coin shall be distributed among the soldiers, detachments of whom are in attendance for the purpose. The bags are then brought out, and laid on the flags in front of the Divan. And now succeeds a scene of puerile enjoyment, which none but a Turk could relish. Certain dishes filled with smoking pilaff of soft rice, are laid at different distances, beside the heaps of coin; and at a signal given, the soldiers start, some to seize one, and some the other, and some both. There are then seen grave old men with long grizzled beards, all smeared with greasy rice, struggling with boys, and rolling over each other on the ground. This folly is highly relished by the sages on the Divan within, who look on with delight till all the bags of money and plates of rice have disappeared.

The last ceremony of the Divan is the reception of ministers of foreign powers, who come here to be duly made fit for presentation to the Sultan. On the day appointed they and their suits assemble at an early hour in the morning, and all the process of deciding causes, distributing money, and running for pilaff, is ostentatiously displayed before them, in order to dazzle, astonish, and impress on those stranger-infidels a high opinion of Turkish superiority. They are allowed to enter the Divan seemingly as spectators, and are left standing in the crowd without notice or respect. On rare occasions, the tired ambassador, if he be from a favoured nation, is allowed a joint-stool to sit on; but such an indulgence is not permitted to the rest: secretaries of legation, dragomans, consuls, &c. are kept standing for several hours, till the whole of the exhibition is displayed. It is then notified to the Sultan, that some giaours are in the Divan, and, on inquiring into their business, that they humbly crave to be admitted into his sublime presence, to prostrate themselves before him. It is now that orders are given to feed, wash, and clothe them, and it is notified that when they are fit to be seen, they will be admitted; and this is done accordingly. Joint-stools are brought in, on which are placed metal trays, without cloth, knife, or fork; and every one helps himself with his fingers, including the ambassador. After this scrambling and tumultuous refreshment, water is poured on the smeared and greasy persons who partake of it. They are then led forth to a large tree in the court, where a heap of pellises of various qualities lie on the pavement, shaken out of bags in which they were brought. From this, every person to be admitted to the presence takes one, and, having wrapped himself in it, he is seized by the collar, and dragged into the presence of the Sultan, as we have elsewhere noticed. Such were the unseemly ceremonies used on these occasions only a few years ago; but, like other Turkish barbarisms, they are daily disappearing, and the introduction of the representative of one sovereign to the audience of another, is approaching to the decorum of European usages.

Our illustration presents the gate Capi Arasi, leading from the first to the second court of the seraglio, where the Divan is held, and so it is the entrance to it. It is also the place where delinquents are led for punishment, and thus originated the Turkish expression of a man deserving to be sent “between gates,” which the name Capi Arasi signifies. Here it is that the executioners sit, and the implements of their trade hang on the walls round about them, forming a horrid combination. Yet it was here, and in this company, that foreign ambassadors were obliged to wait till orders were issued to admit them into the court of the Divan. Crowds of hateful dogs are usually seen here. As they are called “the consummators of Turkish justice,” by lacerating and devouring the bodies of criminals exposed in the streets after decapitation, so, as it were by instinct, they seem fond of congregating with their fellow-executioners.

THE MEDÂK, OR EASTERN STORY-TELLER.

CONSTANTINOPLE

T. Allom. J. Jenkins.

The Turks have no theatres where various persons habited in appropriate costume represent the manners, usages, and feelings of real life, among artificial scenery, which imitates objects of nature and art; they have no resemblance of woods, or gardens, or streets, or houses, where men and women, supporting various characters, meet as in the daily intercourse of society, and every thing combines to create the delusions of dramatic representation. All these things are considered as coming under the prohibition of making the likeness of anything; and proscribed, with the art of painting, as idolatrous representations. They have, however, occasionally something approaching to our plays; where more than one character appears in a naked room, or in the open air, in front of a kiosk, while the spectators look from the windows, or form a circle round the performers. On these occasions some very gross indecencies take place, and the gravity and sense of decorum of a Turk is laid aside. They permit, and seem to enjoy, in these representations, a violation of morals and propriety, which, in real life, they would punish with the greatest severity. The sultans themselves are often present at such exhibitions, and set the example of encouraging them.

Such things, however, are rare, only of extraordinary occurrence, and on memorable occasions; but the Medâk, or Story-teller, is a source of every-day enjoyment. This is a very important personage, and an essential part of Turkish amusement. He enacts by himself, in a monologue, various characters, and with a spirit and fidelity quite astonishing, considering the inflexible and taciturn disposition of the people. The admirable manner in which one unassisted individual supports the representations of various persons, the versatility with which he adopts their countenance, attitude, and phraseology, are so excellent, that Frank residents, who have been accustomed to the perfection of the scenic art in their own country, are highly delighted with this Turkish drollery, and they are constant spectators, not only for amusement, but to perfect themselves in the language by hearing it under its various inflections, and thus acquire a knowledge which a common master could never impart; they also go to see different traits of manners, and of real life faithfully represented, which a long residence in the country would hardly allow them an opportunity of witnessing. The Medâk, therefore, is a public character, of importance to strangers as well as others.

The subjects he selects for representation are Oriental stories, some actually taken from, and all greatly resembling the tales of the Arabian Nights, in which the incidents and persons seem to have the same origin. Sometimes the corruption of a cadi, and his manner of administering justice, are detailed with considerable humour and sarcastic severity. Sometimes a Turkish proverb is illustrated, and forms, as it were, the text of his details; and the effects of various vices and virtues are exhibited, so as to form an excellent moral lesson. Among the proverbs illustrated and dramatized, the following are the most usual. “In a cart drawn by a buffalo, you may catch a hare.” “It is not by saying ‘honey, honey,’ it will come to your mouth.” “A man cannot carry two melons under one arm.” “Though your enemy be no bigger than an ant, suppose him as large as an elephant.” “More flies are caught by a drop of honey, than by a hogshead of vinegar.” “He who rides only a borrowed horse, does not do so often.” “Do not trust to the whiteness of a turban.” “Though the tongue has no bones in it, it breaks many.” In these and similar ones, the effects of industry, perseverance, idleness, caution, cunning, and such other moral qualities, are illustrated in a manner equally striking and amusing. In these representations, he passes from grave to gay with a singular and happy facility, seemingly unattainable by the dullness and limited capabilities of a Turk. The volatile Greek at his strokes of pathos or humour sheds tears, or bursts out into uncontrollable laughter−the grave Armenian, incapable of higher excitement, looks sad, or smiles−while the phlegmatic Turk, though profoundly attentive to the various passions so admirably depicted by his countryman, scarcely alters a feature of his face.

The place where the Medâk exhibits is usually a coffee-house. He generally has a small table, placed before him, which he either stands behind or sits on. His cuffs are turned up, and he holds generally a small stick in his hand. If he illustrates a proverb, he gives it out as a text, and then commences his story. He introduces individuals of all sects and nations, and imitates with admirable precision the language of each. But he is particularly fond of introducing the Jews, whose imperfect pronunciation of every language which they attempt to utter, presents him with a happy subject of caricature. Thus he imitates the multifarious tones of all the varieties of people in the Turkish empire, with a happy selection of all their characteristic expressions.