полная версия

полная версияConstantinople and the Scenery of the Seven Churches of Asia Minor

Robert Walsh

Constantinople and the Scenery of the Seven Churches of Asia Minor / Series One and Series Two in one Volume

PREFACE

Nothing can form a stronger contrast in modern times, than Asiatic and European Turkey. The first preserves its character unchanged−men and things still display the permanency of Oriental usages; and they are now as they have been, and will probably continue to be, for an indefinite period.

Not so the second−Constantinople having for centuries exhibited the singular and extraordinary spectacle of a Mahomedan town in a Christian region, and stood still while all about it were advancing in the march of improvement, has at length, as suddenly as unexpectedly, been roused from its slumbering stupidity; the city and its inhabitants are daily undergoing a change as extraordinary as unhoped for; and the present generation will see with astonishment, that revolution of usages and opinions, during a single life, which has not happened in any other country in revolving centuries.

The traveller who visited Constantinople ten years ago, saw the military a mere rabble, without order or discipline, every soldier moving after his own manner, and clad and armed after his own fashion; he now sees them formed into regular regiments, clothed in uniform, exercised in a system of tactics, and as amenable to discipline as a corps of German infantry. He saw the Sultan, the model of an Oriental despot, exhibited periodically to his subjects with gorgeous display; or to the representatives of his brother sovereigns, gloomy and mysterious, in some dark recess of his Seraglio: he now sees him daily, in European costume, in constant and familiar intercourse with all people−abroad, driving four-in-hand in a gay chariot, like a gentleman of Paris or London; and at home, receiving foreigners with the courtesies and usages of polished life. He formerly saw his kiosks with wooden projecting balconies, having dismal windows that excluded light, and jalousies closed up from all spectators; he now sees him in a noble palace, on which the arts have been exhausted to render it as beautiful and commodious as that of a European sovereign. He formerly saw the people listening to nothing, and knowing nothing, but the extravagant fictions of story-tellers; he now sees them reading with avidity the daily newspapers published in the capital, and enlightened by the realities of passing events.

It is thus that the former state of things is hurrying away, and he who visits the capital to witness the singularities that marked it, will be disappointed. It is true, it possesses beauties which no revolution of opinions, or change of events, can alter. Its seven romantic hills, its Golden Horn, its lovely Bosphorus, its exuberant vegetation, its robust and comely people, will still exist, as the permanent characters of nature: but the swelling dome, the crescent-crowned spire, the taper minaret, the shouting muezzin, the vast cemetery, the gigantic cypress, the snow-white turban, the beniche of vivid colours, the feature-covering yasmak, the light caïque, the clumsy arrhuba, the arched bazaar−all the distinctive peculiarities of a Turkish town−will soon merge into the uniformity of European things, and, if the innovation proceed as rapidly as it has hitherto done, leave scarce a trace behind them.

To preserve the evanescent features of this magnificent city, and present it to posterity as it was, must be an object of no small interest; but the most elaborate descriptions will fail to effect it.

It is, therefore, to catch the fleeting pictures while they yet exist, and transmit them in visible forms to posterity, that the present work has been undertaken, and, that nothing might be wanting, Asiatic subjects are introduced; thus presenting, not only the Turk of one region as he was, but of another as he is, and will continue to be.

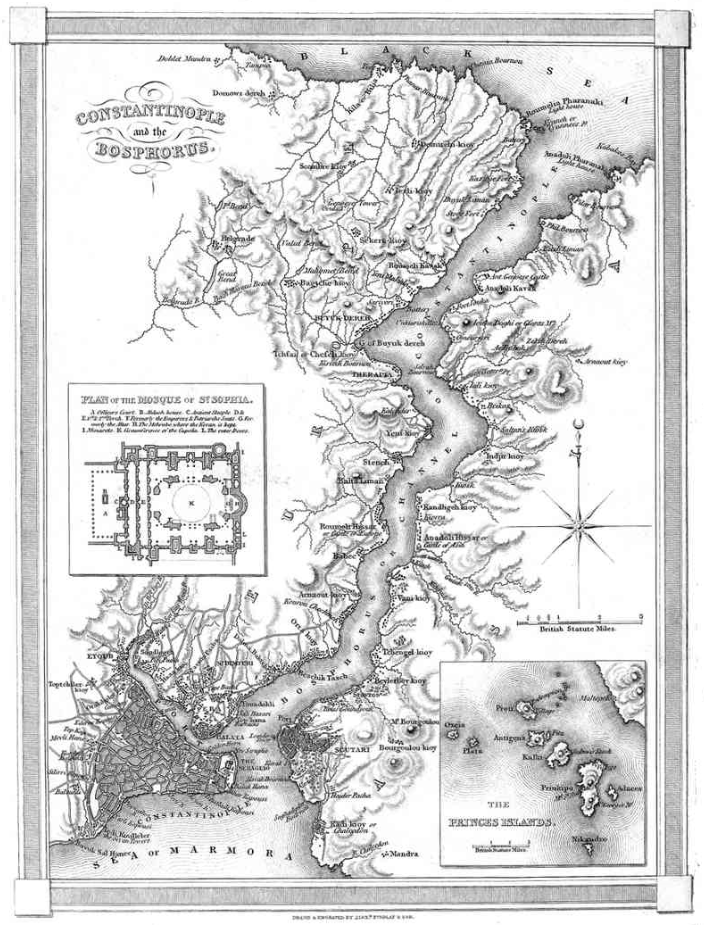

The Views are accompanied with letter-press, describing the usages, customs, and opinions of the people, as ancillary to the pictorial representations; and a Map of the Bosphorus is added, pointing out localities, and directing attention to the spot on which the reality stood or still stands. To complete the whole, an historical sketch of the city from its foundation is annexed, with a chronological series of its Emperors and Sultans to the present day; thus combining a concise history of persons and events, with copious details of its several parts, and vivid and characteristic representations of its objects.

ROBERT WALSH.

DRAWN & ENGRAVED BY ALEXR FINLAY & SON.

CONSTANTINOPLE and the BOSPHORUS.

HISTORICAL SKETCH OF CONSTANTINOPLE

The first mercantile expedition undertaken by the Greeks, to a distant country, was that to Colchis, the eastern extremity of the Black Sea, to bring back the allegorical golden fleece. This distant and perilous voyage, could not fail, in that rude age, to excite the imagination; so the poets have adorned its historical details with all the fascinations of fiction; the bold mariners who embarked in the ship Argo are dignified with the qualities of heroes, and their adventures swelled into portentous and preternatural events. The Symplegades were placed at the entrance of this dark sea, which closed upon and crushed the daring ships that presumed to penetrate into its mysteries, and so for ever shut out all access to strangers. But the intrepid sailors, whose names are handed down to posterity for their extraordinary physical powers, overcame every difficulty; and Jason, the Columbus of the ancient world, returned in safety with his golden freight. From that time the hitherto impervious sea changed its name. It had been called by the inhospitable appellation of Axenos, because it was inaccessible to strangers; it was now named Euxenos, as no longer repelling, but, on the contrary, inviting foreigners to its shores.

The dark Euxine, and all its visionary dangers, soon became familiar to the enterprising Greeks, and colonies were every where planted on the narrow waters that led to it. Little, however, was understood of the advantages of selecting a site for these young cities; and one of the first on record still remains, to attest the ignorance of the founders. In the year 685 before the Christian era, Argias led a colony from Megara, which he settled at the mouth of the Bosphorus. The site selected for the town was the shore of a shallow bay that indented the Asiatic coast, and was exposed to every wind. It was first called Procerastes, afterwards Colpusa, and finally Chalcedon.

A few years had brought experience to the Greeks, and a more mature judgment led them to select a better situation. About thirty years after, Byzas led another colony from Megara. He consulted the oracle, as was usual in such cases, where he should erect his new city; and the answer was, of course, wrapt in mystery. He was directed to place it “opposite the city of the blind men.” On exploring the mouth of the strait, he discovered, on the European shore, a situation unrivalled perhaps by any other in the world. A peninsula of gradual elevation was washed on one side by the Propontis, and on the other by a magnificent harbour, broad and deep, and sheltered from every wind, capable of holding in security all the ships of all known nations, and just within and commanding the mouth of the great watery thoroughfare to the newly discovered sea. Here they built their city, and called it Byzantium, after its founder Byzas, who, from his singular judgment and sagacity in maritime affairs, was also denominated the Son of Neptune. The accomplishment of the mysterious oracle was now apparent. The striking contrast between his selection and that of his predecessors on the opposite coast, caused their settlement to be called “the City of the Blind Men,” because its founder overlooked, or could not see the beauties and benefits of the site of Byzantium, when he had full liberty to choose. Byzantium was afterwards enlarged and re-edified by Pausanias, a Spartan, and, in process of time, from the singular superiority of its commanding situation and local advantages, became one of the most important of the free and independent republics of the Greeks, and suffered the penalty of its prosperity by becoming an object of envy and cupidity to its contemporaries.

The sovereigns of Bythinia and Macedon were the most persevering in their attacks. A siege by the latter is rendered memorable by a circumstance connected with it. Philip sat down before the city, and attempted to take it by surprise. A dark night was selected for the purpose, when it was hoped the citizens could not be prepared to resist the concealed and sudden attack. The moon, however, appeared to emerge from the black sky with more than common brilliancy, and illumined distinctly every object around the city. The obscure assailants were thus unexpectedly exposed to view, and discovered; and the citizens, now upon their guard, easily repulsed them. Grateful for this seasonable and supposed miraculous interference of the goddess, the Byzantines adopted Diana as their tutelar deity, and depicted her under the form of a crescent. By this emblem she is represented on the coins of the city, still extant, with the legend ΒΥΣΑΝΤ ΣΩΤ, implying that she was the “saviour of Byzantium.” This emblem of the ancient city was adopted by Constantine, when he transferred hither the seat of empire, and it was retained by the Turks, like many other representations, when they took possession of it. The crescent therefore is still its designation, not as a Mohammedan, but a Byzantine emblem.

After many struggles, with more powerful nations, to maintain its independence, Byzantium attracted the attention of the Romans. In the contests of the different competitors for the empire, the possession or alliance of this city was of much importance, not merely on account of its power and opulence, but because it was the great passage from Europe to Asia. It was garrisoned by a strong force, and no less than five hundred vessels were moored in its capacious harbour. When Severus and Niger engaged in hostilities, this city adhered to the latter, many of whose party fled thither, and found a secure asylum behind fortifications which were deemed impregnable. Siege was laid to it by the victorious Severus, but it repelled all his assaults for three years. Its natural strength was increased by the skill of an engineer named Priscus, who, like another Archimedes, defended this second Syracuse by the exercise of his extraordinary mechanical powers. When it did yield, it fell not by force, but famine. Encompassed by the great Roman armies on every side, its supplies ware at length cut off, as the skill of the artist was incapable of alleviating the sufferings of starvation. By the cruel and atrocious policy of the most enlightened ages of the pagan world, the magistrates and soldiers were put to death without mercy, for their gallant defence, to deter others from similar perseverance; and to destroy for ever its power and importance, its privileges were suppressed, its walls demolished, its means of defence taken away; and in this state it continued, an obscure village, subject to its neighbours the Perenthians, till it was unexpectedly selected to become the great capital of the Roman empire, an event rendered deeply interesting because it was connected with the extinction of paganism, and the acknowledgment of Christianity, as the recognised and accredited religion of the civilized world.

The emperor Diocletian, impelled by his cruel colleague Galerius, had consented to the extermination of the Christians, now becoming a numerous and increasing community all over the Roman empire: decrees were issued for this purpose, and so persevering and extreme were the efforts made to effect it, that medals were struck and columns erected with inscriptions, implying that “the superstition of Christianity was utterly extirpated, and the worship of the gods restored.” But while, to all human probability, it was thus destroyed, the hand of Providence was visibly extended for its preservation; and mankind with astonishment saw the sacred flame revive from its ashes, and burn with a more vivid light than ever, and the head of a mighty empire adopt its tenets from a conviction of their truth, when his predecessor had boasted of its extinction on account of its falsehood. This first Christian emperor was Constantine.

Christian writers assert that he, like St. Paul, was converted by a sensible miracle while journeying along a public way. There were at this time six competitors for the Roman empire. Constantine was advancing towards Rome to oppose one of them−Maxentius: buried in deep thought at the almost inextricable difficulties of his situation, surrounded by enemies, he was suddenly roused by the appearance of a bright and shining light; and looking up, he perceived the representation of a brilliant cross in the sky, with a notification, that it was under that symbol he should conquer. Whether this was some atmospheric phenomenon which his vivid imagination converted into such an object, it is unnecessary to inquire. It is certain that the effects were equally beneficial to mankind. He immediately adopted the emblem as the imperial standard, and under it he marched from victory to victory. His last enemy and rival was Licinius, who commanded in the east, and established himself on the remains of Byzantium, as his strongest position: but from this he was driven by Constantine, who was now acknowledged sole emperor of the East.

His first care was to build a city near the centre of his vast empire, which should control, at the same time, the Persian power in the east, and the barbarians on the north, who, from the Danube and the Tanais, were continually making inroads on his subjects. It was with this view that Diocletian had already selected Nicomedia as his residence; but any imitation of that persecutor of Christianity, was revolting to the new and sincere convert to the faith,—so he sought another situation. He at one time had determined on the site of ancient Troy, not only as commanding the entrance of the Hellespont, and so of all the straits which led to the Euxine Sea, but because this was the country of his Roman ancestors, to whom, like Augustus, he was fond of claiming kindred. He was at length induced to adopt the spot on which he had defeated his last enemy, and he was confirmed in his choice by a vision. While examining the situation, he fell asleep; and the genius who presided over mortal slumbers, appeared to him in a dream. She seemed the form of a venerable matron, far advanced in life, and infirm under the pressure of many years and various injuries. Suddenly she assumed the appearance of a young and blooming virgin; and he was so struck with the beautiful transition, that he felt a pride and pleasure in adorning her person with all the ornaments and ensigns of his own imperial power. On awaking from his dream, he thought himself bound to obey what he considered a celestial warning, and forthwith commenced his project. The site chosen had all the advantages which nature could possibly confer upon any single spot. It was shut in from hostile attack, while it was thrown open to every commercial benefit. Almost within sight, and within an easily accessible distance, were Egypt and Africa, with all the riches of the south and west, on the one hand; on the other were Pontus, Persia, and the indolent and luxurious East. The Mediterranean sent up its wealth by the Hellespont, and the Euxine sent hers down by the Bosphorus. The climate was the most bland and temperate to be found on the surface of the globe; the soil, the most fertile in every production of the earth; and the harbour, the most secure and capacious that ever opened its bosom to the navigation of mankind: winding round its promontories, and swelling to its base, it resembled the cornucopia of Amalthea, filled with fruits of different kinds, and was thence called “The Golden Horn.”

His first care was to mark out the boundaries. He advanced on foot with a lance in his hand, heading a solemn procession, ordering its line of march to be carefully noted down as the new limits. The circuit he took so far exceeded expectation, that his attendants ventured to remonstrate with him on the immensity of the circumference. He replied, he would go on till that Being who had ordered his enterprise, and whom he saw walking before him, should think proper to stop. In this perambulation he proceeded round six of the hills on which the modern city is built. Having marked out the area, his next care was to fill it with edifices. On one side of him rose the forests of Mount Hæmus, whose arms ramify to the Euxine and the mouth of the Bosphorus, covered with wood; these gave him an inexhaustible supply of timber, which the current of the strait floated in a few hours into his harbour, and which centuries of use have hardly yet thinned, or at all exhausted. On the other, at no great distance, was Perconessus, an island of marble rising out of the sea, affording that material ready to be conveyed by water also into his harbour, and in such abundance, that it affords at this day, to the present masters of the city, an inexhaustible store, and lends its name to the sea on whose shores it so abounds.

The great materials being thus at hand, artists were wanted to work them up. So much, however, had the arts declined, that none could be found to execute the emperor’s designs, and it was necessary to found schools every where, to instruct scholars for the purpose; and, as the pupils became improved and competent, they were despatched in haste to the new city. But though architects might be thus created for the ordinary civil purposes, it was impossible to renovate the genius of sculpture, or form anew a Phidias or a Praxiteles. Orders therefore were sent to collect whatever specimens could be found of the great artists of antiquity; and, like Napoleon in modern times, he stripped all other cities of their treasures, to adorn his own capital. Historians record the details of particular works of art deposited in this great and gorgeous city, as it rose under the plastic hand of its founder, scarcely a trace of which is to be seen at the present day, and the few that remain will be described more minutely hereafter. Suffice it to say, that the baths of Zeuxippus were adorned with various sculptured marble, and sixty bronze statues of the finest workmanship; that the Hippodrome, or race-course, four hundred paces long, was filled with pillars and obelisks; a public college, a circus, two theatres, eight public and one hundred and fifty private baths, five granaries, eight aqueducts and reservoirs for water, four halls for the meeting of the senate and courts of justice, fourteen temples, fourteen palaces, and four thousand three hundred and eighty-eight domes, resembling palaces, in which resided the nobility of the city, seemed to rise, as if by magic, under the hand of the active and energetic emperor.

But the erection that gives this city perhaps its greatest interest, and it is one of the few that has escaped the hand of time or accident, is that which commemorates his conversion to Christianity. He not only placed the Christian standard on the coins of his new city, but proclaimed that the new city itself was dedicated to Christ. Among his columns was one of red porphyry, resting on a base of marble; between both he deposited what was said to be one of the nails which had fastened our Saviour to the cross, and a part of one of the miraculous loaves with which he had fed the five thousand; and he inscribed on the base an epigram in Greek, importing that he had dedicated the city to Christ, and “placed it under his protection, as the Ruler and Governor of the world.” Whenever he passed the pillar, he descended from his horse, and caused his attendants to do the same; and in such reverence did he hold it, that he ordered it, and the place in which it stood, to be called “The Sacred.” The pillar still stands. The dedication of this first Christian city took place on the 11th of May, A. D. 330.

Constantine left three sons, who succeeded him; and numerous relatives, who all, with one exception, adopted the religious opinions he had embraced. This was Julian, his nephew. He had been early instructed in the doctrines and duties of the new faith, had taken orders, and read the Scriptures publicly to the people; but meeting with the sceptic philosophers of Asia, his faith was shaken, and, when the empire descended to him, he openly abandoned it. With some estimable qualities, was joined a superstitious weakness, which would not suffer him to rest in the philosophic rejection of Christianity. He revived, in its place, all the revolting absurdities of heathenism. In the language of the historian Socrates, “He was greatly afraid of dæmons, and was continually sacrificing to their idols.” He therefore not only erased the Christian emblems from his coins, but he replaced them with Serapis, Anubis, and other deities of Egyptian superstition. He was killed on the banks of the Euphrates, in an expedition against the Persians, having, happily for mankind, reigned but one year and eight months, and established for himself the never-to-be-forgotten name of “Julian the Apostate.”

The family of Constantine ended with Julian, and, as the first had endeavoured to establish Christianity as the religion of this new capital of the world, so the last had endeavoured to eradicate it. But his successor Jovian set himself to repair the injury. He was with Julian’s army at the time of his defeat and death, and with great courage and conduct extricated it from the difficulties with which it was surrounded. He immediately proclaimed the restoration of Christianity, and, as the most decided and speedy way of circulating his opinions, he had its emblems impressed on his first coinage. He is there represented following on horseback the standard of the Cross, as Constantine had done, and so was safely led out of similar danger. He caused new temples to be raised to Christian worship, with tablets or inscriptions importing the cause of their erection, some of which still continue in their primitive state. He reigned only eight months; but even that short period was sufficient to revive a faith so connected with human happiness, and so impressed on the human heart, that little encouragement was required to call it forth every where into action.

From the time of Jovian, Christianity remained the unobstructed religion of Constantinople; but an effort was made in the reign of Theodosius to revive paganism in the old city of Rome. The senate, who had a tendency to the ancient worship, requested that the altar of Victory, which was removed, might be restored; and an attempt was made to recall the Egyptian deities. On this occasion, the emperor issued the memorable decree, that “no one should presume to worship an idol by sacrifice.” The globe had been a favourite emblem of his predecessors, surmounted with symbols of their families, some with an eagle, some with a victory, and some with a phœnix; but Theodosius removed them, and placed a cross upon it, intimating the triumph of Christianity over the whole earth; and this seems to have been the origin of the globe and cross, which many Christian monarchs, as well as our own, use at their coronations. From this time, heathen mythology sunk into general contempt, and was expelled from the city of Constantinople, where the inquisitive minds of cultivated men had detected its absurdities: it continued to linger yet a while longer, among the pagi, or villages of the country, and its professors were for that reason called pagani, or pagans, a name by which they are known at this day. The Christian city had so increased, that it was necessary to enlarge its limits. Theodosius ran a new wall outside the former, from sea to sea, which took within its extent the seventh or last hill. The whole was now enclosed by three walls, including a triangular area, of which old Byzantium was the apex. Two of its walls were washed by the waters of the Propontis and the Golden Horn, and the third separated the city from the country, the whole circuit being twelve miles. These walls, with their twenty-nine gates, opening on the land and sea, and the area they enclose, remain without augmentation or diminution, still unaltered in shape or size, under all the vicissitudes of the city, for fifteen hundred years.