полная версия

полная версияConstantinople and the Scenery of the Seven Churches of Asia Minor

As an appropriate object in our illustration, the stork is seen crowning the summit of a tower with its slender form and elongated limbs. This bird has been in all ages a never-failing inhabitant of Oriental towns, noted and celebrated for its qualities, which have conferred upon it its name; it is called in Hebrew chesadao, which implies “mercy or piety,” and alludes to the known tenderness and attachment of the bird to its parents, whom it is reported never to desert in advanced age, but feeds and protects even at the hazard of its own safety: its emigrating qualities are noticed by the most ancient writers: Jeremiah says, “Yea, the stork in the heavens knoweth her appointed time;”23 and nothing can be more striking than their appearance at the approaching period. They collect together in large detachments, and are seen wheeling about at an immense height in the air, above some lofty eminence, before their forward progress commences, like scouts sent out to reconnoitre the way; their white bodies, long-projected red legs, and curved necks turning to every point of the compass as if examining the road, give them a singular picturesque appearance, while the light, reflected from their bright colours, causes them to be distinctly seen at a great distance in the air.

When they do depart for distant regions, their vigilance and precaution have been extolled by many writers; their leader appoints certain sentinels, to watch where they alight for repose; this they must do standing on one leg, while they hold a stone grasped in the claw of the other. If they are known to have dropped the stone, it is a presumption they have slept on their post, and are punished accordingly; when they arrive at the place of their destination, they take note of the loiterer who comes last, and he also suffers, as an example to the negligent. To the ingenious pictures of ancient writers and others, which tradition has handed down to us, the moderns have added many more.−The Psalmist says, “As for the stork, the fir-trees are her house,”24 and here they build at the present day, and seem to take under their protection a multitude of small birds, who make their nests among the materials of the larger ones, and form a numerous community. It is pleasing to see the harmony and affection that subsist between them; and the sense of security the smaller evince under the protection of their larger friends. Many of these are birds of passage also, but their size, and the feebleness of their flight, seem to preclude the possibility of a long journey; yet they all disappear together, so the Turks affirm that the storks take their little friends upon their backs, and every one carries as many as he can stow between his wings. It is certain, that when the storks disappear in the night, on the next day not a small bird is to be seen left behind them. From a belief in this and similar tales, the Turks confer a sacred character on the bird; and besides their general indisposition to hurt any animal in a state of nature, they peculiarly inhibit the destruction of a stork. Whoever injures one, incurs considerable personal danger. For this feeling, there is some reasonable foundation:−the marshes abound with reptiles of all kinds, generated in immense numbers in the rank slime of the soil. They are providentially the food of the stork, and, but for their consumption in this way, would so increase as to render the country uninhabitable by man. It appears from Pliny, that their utility for this purpose was so felt, that the penalty of death was decreed against any man who destroyed a stork.

Though the bird is seen in great numbers in all Oriental towns, Pergamus seems its favourite haunt; the inhabitants feel for it a fraternal regard, call it by endearing names, and affirm their attachment is so mutual, that it follows the Moslem people into whatever part of the globe they emigrate. They erect on their houses frame-work of wood, to induce the stork to build there; the public edifices are covered with them; the mosques and their minarets are full of their nests, and on every “jutting pier, buttress, and coign of “vantage” is seen their “procreant cradle.” Below, they strut about the town with perfect familiarity, and are never disturbed by those they meet; and their tall, slender heads are seen rising among the turbans and calpacs of a crowded street. So jealous are the Turks of the friendship of this bird, that they affirm it never builds on an edifice inhabited by any but a Mussulman. It is certain they are seldom seen in the Greek and Armenian quarters; it is probable the timid Christians, from the apprehension of exciting the envy of their masters, discourage or repel the stork whenever it approaches their habitations.

MOSQUE OF SANTA SOPHIA, AND FOUNTAIN OF THE SERAGLIO.

CONSTANTINOPLE

Drawn by Leitch. Sketched by T. Allom. Engraved by J. Sands.

This is another view of the same objects as were given in a former illustration; but their are presented under a different aspect. In the centre of the front is the Fountain built by Achmet, with its rich display of gilded arabesque, on a bright blue and red ground; on the left are the various edifices connected with Santa Sophia, the vast aërial dome swelling above them, and intended to represent a section of the concave firmament; and on the right is the Babu Humayun, or, “Sublime Porte,” already described.

From this gate is seen, in perspective, descending the hill, the turreted and battlemented walls of the Seraglio gardens, running down to the harbour, and supposed to be the remains of that very ancient fortification which marked the city of Byzantium, and cut off the apex of the triangle which it occupied. The street below it is the great avenue leading from the lower parts of the city to the Seraglio, and many characteristic displays of Turkish manners are exhibited in it.

When an audience is granted by the sultan to a Frank ambassador, it is notified to him by the dragoman, and a very early hour is appointed for the purpose. Horses, richly caparisoned, are sent to convey him and his suite; and, before light in the morning, if it be not in summer, they mount in their grandest costumes. As all the Frank ministers reside in Pera, they have the harbour to cross, so they clatter down the steep and rugged streets leading to the water, at the imminent hazard of breaking their limbs, and display any thing but a grand and dignified procession. Having passed the harbour, they are received in a small mean coffee-house on the water-edge, where pipes and coffee are presented, after which they resume their march on fresh horses. There stands a great tree, at the point where some streets meet; here the cortege are directed to halt, and here they are condemned to wait till the grand vizir, and other functionaries, are pleased to issue from his bureau, in the Downing-street of Constantinople. The contemptuous manner in which infidel ministers were formerly treated, here began to display itself. Instead of the respect with which the representative of a brother sovereign ought to be received, he was kept standing in an open, dirty street, sometimes under heavy rain, for an hour or more, without the slightest attention shown, or notice taken of him, except being stared at, or called opprobrious names, muttered by some fanatic Turk as he passed by. At length the vizir was seen slowly moving down from his office; and it was supposed that he would courteously greet the expected ambassador, and apologize for his delay:−but no−he passed on with the most imperturbable gravity; not even condescending to look at the ambassador, or seeming to know that he and his suite were not part of the vulgar crowd. They were then permitted to move on, and follow, at an humble distance, the vizir up this street, till they entered the Babu Humayun; and here commenced a new series of degradations, which have been already noticed. These barbarisms, however, are now passing away, and, among other ameliorations of Turkish manners, the sultan receives the representatives of his brother sovereigns in a more becoming manner.

As the houses in the street overlook the gardens of the Seraglio, strangers, who dared not enter, are led, by an idle and dangerous curiosity, sometimes to attempt to overlook the walls of the sacred enclosure, and see what is passing on the other side; and stories are related of persons sacrificed to the perilous effort. Some even who had no such object in view, have fallen victims to the jealousy of the harem. On one occasion, the friend of an Armenian merchant, who had a house here, brought a telescope, to examine the distant objects on the other side of the sea of Marmora: unfortunately the view extended across the gardens, and, while he was intently engaged in tracing the declivities of Mount Olympus, the sultan passed below, and caught with his eye the glitter of the glass of the telescope. Two chaoueshes were instantly despatched, who entered the house, and the unfortunate man found himself seized behind; and, before he had time to take the fatal instrument from his eye, a bowstring was put round his neck, and he was strangled at the window, in view of the sultan, who, it is said, waited below to assure himself of the execution.

But this street witnessed a still more terrible display of Turkish vengeance. After the awful destruction of the Janissaries at the Atmeidan, they were everywhere hunted down like wild beasts through the city. Sometimes they were killed wherever they were overtaken, and their bodies suffered to remain weltering on the spot. Sometimes they were brought to some enclosure, where they were kept till a number was collected together, when armed men rushed among them, and they were destroyed in a mass. Some of them were dragged into this street from the neighbouring ones, as it was the great avenue leading to the Seraglio, and there sacrificed as a grateful offering to the sultan. Their heads were cut off, their trunks were drawn up at each side of the street, and for three days, the appointed time for executed bodies to remain so exposed, he passed up and down between this Oriental display of headless men, lining the street to do the sovereign honour; thus realizing, only a few years since, in a European capital, the horrid exhibitions in which a Bajazet or a Tamerlane delighted, centuries ago.

Along the wall near the great gate was the favourite spot selected for the suspension of those trophies which marked the triumph of Islamism over Christianity. On every victory obtained during their European wars, the standards taken from Germans, Russians, Hungarians, and other powers, were displayed here; and more recently the captive flags of the Greeks were constantly seen fluttering, in an inverted position, over heaps of ears and noses which were piled below. Among them were several on which was depicted the cross, and various representations of Christian events, but particularly the resurrection which was labelled “Anastasis,” intended to be emblematic of their political resurrection. But of all the standards, that of Ipsera was the most interesting. After a gallant and almost incredible defence of this little island against the Turkish fleet, which surrounded it on all sides, and poured in numerous troops at every point, these few brave defenders were compelled to take refuge in their last fortress. Here they displayed their flag inscribed with their determination to die, and their actions coincided with the inscription. The Turks were permitted without much opposition to enter the fortress, and, when it was filled with the crowd, the whole was blown into the air. The last remnant of the Ipsariots, with an equal number of Turks, perished in one indiscriminate carnage. The broad flag which had floated over the self-devoted fortress, was brought in triumph, and suspended on this wall. It was of large size, and inscribed ΗΛΑΗΘΤ, the Greek anagram of “Death or Freedom;” and while the passenger “contemplated its scorched and torn remnants hanging over the mutilated remains of the brave spirits who unfurled it, it forcibly recalled to his mind that desperate devotion which in all ages distinguished the Greeks.”

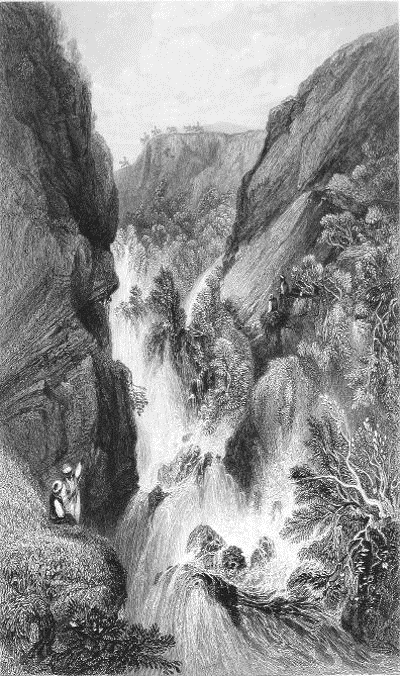

PASS AND WATERFALL IN THE BALKAN MOUNTAINS

Drawn fom Nature by F. Hervé E. Benjamin.

This celebrated chain presents continually to the traveller a succession of objects sometimes minute and picturesque, sometimes vast and sublime. In the recesses between the high ridges, the scenery is rural and pastoral, equalling that of Arcadia; on the summits of the mountains, all seems thunder-splintered rocks and riven precipices, where the ear is stunned with the roar of cataracts, as the eye is astonished and the senses are appalled by the vast chasms through which they rush. The Balkans are seldom seen covered with snows, and the waters are rarely arrested by ice. At no season is observed, as in the Alps, frost-suspended waterfalls,

“Whose idle torrents only seem to roar;”but the sound of the bursting cataract never ceases, and the mountain-streams, fed by continued showers, do not depend on the solution of snows, but are always tumbling down the steeps and rushing through the ravines.

The beautiful waterfall given in our illustration, occurs in the pass by Bazarjik, not far from the village of Yenikui, half way up the mountain-side. In several parts of this pass, the vegetation is extremely luxuriant. Sometimes vast forest-trees are seen rising from the depths of chasms, and shooting their giant trunks, as they struggle up for light and air, till they reach the summit, and then, and not till then, expanding their noble foliage; while the eye of the traveller, looking down into the chasm from which they issue, is lost in the immensity of the depth, and cannot trace the vast stems of the trees to the ground. Sometimes the vegetation is of a very different character: the mountains are celebrated for the abundance of plants and shrubs used in dyeing, and parties set out every year, in the season, from Adrianople, Philopopoli, and other towns, to collect them. Nothing can then surpass the rich and glowing hue which clothes the surface. The deep crimson of the sumachs, with the varying colours of yellow, brown, purple, and the dark tints of the overhanging evergreens, give a beautiful variety, exceeding perhaps that of any other region on the surface of the earth.

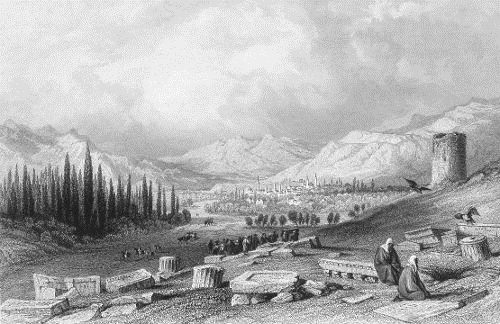

CITY OF THYATIRA.

ASIA MINOR

T. Allom. S. Fisher.

The notice of Thyatira in profane history is brief. It is enumerated as one of the cities of Lydia, but not distinguished by any circumstances that would confer upon it celebrity among the Greek free cities of this region. When the all-conquering Romans possessed themselves of Asia, it fell under their power, and is mentioned by their historians. Livy says, Antiochus collected his forces at Thyatira, when he marched against their invading legions; he was defeated at Magnesia, and Thyatira with all the surrounding territories merged into a Roman province.

When Christianity began to expand itself, the inhabitants of this place early evinced a disposition to embrace its new doctrines. St. Paul, in his travels in Greece, met at Philippi a woman of Thyatira; she was concerned in the sale of purple, either the dye or the dyed cloth, for which the region in which her city was situated was then famous. It was extracted from the shell-fish abounding on the sea-coasts, and was in extensive demand as an article of commerce, used on various important occasions. It was selected by the Jews for the curtains of the tabernacle and the robes of the priests. Among Gentiles, the Chaldeans clothed their idols, and the Persians their great men, in purple; for Daniel was honoured with a robe of that colour when interpreting Belshazzar’s dream, and Mordecai was arrayed in it when he was raised to the rank of minister of state. Among the Romans, it was the hue most precious, and distinguished their kings and emperors from the time of Tullus Hostilius to Augustus Cæsar. It marked the difference between the patrician and the knight, the youth and the child; the temples of the gods, and the triumphs of mortals, were adorned with it. It was the colour most prized and honoured both in the East and the West of the ancient world.

Lydia, the vender of this precious dye in Europe, which was imported from her own country, when she heard Paul expound the doctrines of Christ, at once embraced them. She was baptized by the apostle, who, at her entreaty, made her house his abode while he remained at Philippi. It is probable that this circumstance may have facilitated the reception of the gospel at Thyatira among the friends and commercial connexions of Lydia. A congregation was immediately after formed there, and the fourth church of the Apocalypse established. It was eulogized by the Evangelist for the good works of the new converts; their charity, their patience, their service in God’s law, and all characters by which the primitive Christians were distinguished; but these high qualities were alloyed by the frailties of a corrupt nature, from which not even the purest Christian state was exempt. A woman named Jezebel, or whose character resembled that infamous one of the Old Testament, influenced and seduced them to evil; and, to reclaim them from their sinful practices, St. John sent them a solemn warning in his divine epistle to the Asiatic churches; but it does not appear with what success, for no further notice is found of the city, and its fate is involved in impenetrable obscurity. Its very site was lost in oblivion, and it was not till about a century and a half since, that travellers set out from Smyrna to ascertain its locality. At a Turkish village some inscriptions were discovered, on one of which was found the words ΚΡΑΤΙΣΤΗ ΘΥΑΤΕΙΡΗΝΩΝ ΒΟΥΛΗ, which seemed to decide the situation of the ancient town; its modern Turkish name is “Akhissar,” or the White Castle.

The town is approached by a long avenue of cypress and poplars, through the vistas of which, the domes and minarets of the mosques are seen shooting up. The background is closed by an amphitheatre of hills, circling the rich plain on which the city stands. On entering it a busy scene presents itself, forming a strong and pleasing contrast to what the mind anticipates in this obscure church of the Apocalypse. Stores, merchant shops, and a busy crowd bustling through them, give it the appearance of a thronged and opulent mart, such as perhaps Thyatira once was, when purple was its staple commodity. It still carries on an extensive trade in cotton wool, and is still famous for the milesia vellera fucata, which formerly conferred celebrity upon its neighbouring city.

The present population of Akhissar amounts to between six and seven thousand inhabitants, of whom 1,500 are Christians of the Greek and Armenian churches, which have each respectively a place of worship. That of the Greeks is very mean, and the earth and numerous graves have so accumulated about it, that it seems half buried, and is approached by a descent of many steps. This process seems to have gone on, so as to obliterate the former Christian edifices which stood here. There exist no traces of them above ground, but in excavating different places, the remains of masonry, to a considerable extent, are discovered, having once, according to tradition, formed the foundation of Christian churches. Shafts of mutilated columns are often found obtruding above the soil in cemeteries and other places−all that exist of buildings once standing on the surface. It is probable that many of these marked fanes dedicated to Diana, whose worship was very extensive in Asia, and not confined to Ephesus; she appears to have been the tutelar deity of Thyatira also, and several inscriptions intimate the extent of her influence and the devotion of her worshippers, till both yielded to a superior power, and the visionary train of heathen deities vanished before the light of the gospel.

Among the very agreeable accessories of this place, is the abundance of pure water with which it is supplied; perennial streams run down from the hills by which it is surrounded, and, meandering through the more level ground, and imparting freshness and fertility to the meadows and gardens of its environs, they enter the city, conducted by various courses formed for the purpose. This fluid, essential to the Osmanli, both as a natural and religious want, they prize and cherish so dearly, that expedients are used to collect it, where it is available. At Ak Hissar they have taken more than common care; they have constructed aqueducts consisting of more than 3000 pipes, from whence the water issues in various channels through the streets, so that the air in the heats of summer is constantly refreshed by the gushing streams, and the ear soothed by the gurgling sound. This water is remarkable for its salutary qualities; it is cool, sweet, limpid, very grateful to the taste, and light of digestion to the stomach. The country about the town is rich and fertile to a high degree, and the air remarkable for its purity, fragrance, and salubrity; it has all those qualities which the bounty of nature has conferred on the lovely plains of Asia Minor, and has invited a larger population than is usually found in those beautiful but now desolate regions.

It is marked, however, by Oriental circumstances revolting to European feelings. It is surrounded by cemeteries more numerous than those found near much larger cities. Attracted, perhaps, by the odour of these charnel-houses, vultures abound here; instead of the cooing of doves which marks Philadelphia, or the crepitation of the stork’s bill which distinguishes Pergamus, the scream of this ravenous and unclean bird is the sound most frequently heard; flocks are constantly seen wheeling round in the air, or lighting by the road-side, covering the fields, and so tame as quite to disregard the approach of a passenger. It is this characteristic of the town which is presented in our illustration−one of its cemeteries strewn over with shafts and mouldings of former buildings now laid to mark the graves, and vultures flapping their wings over the corpse interred below.

CONSTANTINOPLE FROM THE HEIGHTS ABOVE EYOUB

Drawn by W. L. Leitch. Sketched by T. Allom. Engraved by H. Adlard.

This view of the city is a companion for a former. The one presented it as it appears from the mouth of the Golden Horn, the other from its head; and it displays many objects of interest on both sides of a beautiful expanse of water, whose visible circumference may be estimated at 20 miles; the length of the whole harbour being about 15 miles, and its general breadth from 8 to 10 furlongs.

Where the Cydaris and Barbyses discharge themselves into it, the slime and mud carried down by the stream are deposited; and it forms a flat alluvial soil, where extensive manufactories of pottery have been established. As this is in the vicinity of a royal kiosk, it has obtained the name of the Tuileries, for the same reason as the French called their palace−because it was built where a manufactory of tiles had been established. The deposit continues to fill up the harbour, and it is necessary to mark the new-formed shoals, for the direction of vessels, by stakes stuck in the mud, so that this part of the harbour exhibits a curious spectacle of a labyrinth of palisades.

Opposite these, on the northern shore, is the “Yelan Seraï” or Palace of the Serpent forming an imperial residence. Many fantastic reasons are assigned for this name by the Turks, and stories told similar to that of the Kiz-Koulesi. But the simple reason seems to be, that the soil in this place abounds with these reptiles; and they so infested the palace that they were found coiled up on divans, and it was necessary to inspect every couch and seat before it could be occupied; the kiosk has, therefore, been abandoned to decay. Though serpents seem now less numerous than formerly in this place, the deleterious character of it is not lessened. The mal-aria generated, spreads a venomous effluvia, as fatal as that of vipers; this is evinced on the residents. The barrack of the “kombaragees,” or bombardiers, who rendered such signal service to the sultan in extirpating the Janissaries, is not far from it, and their sallow and sickly aspect exhibits proof that health is assailed by an effluvia as mortal as the serpent’s breath.