полная версия

полная версияConstantinople and the Scenery of the Seven Churches of Asia Minor

The little state enrolled on their cloud-capped mountains 2500 palikars of this description, who were objects of fear and respect to all other Albanians when seen below. These were the men, who, under the valiant Scanderbeg, opposed the first inroads of the Turks into the country; and in later times, under the gallant Lambro, attempted to liberate Greece from their yoke.

The usages and opinions of the women all tended to cherish this warlike character. The fountain, as in the days of Homer, was the place where they congregated, and displayed their traits of national character. Scrupulous respect was here paid to precedence. The wife of the bravest man had the first right to fill her urnlike pitcher with water, and then in succession the rest, according to the reputation of their husbands in war. When families quarrelled, no man had permission to interfere, lest by chance he might kill a woman, an act looked upon with horror, and expiated by his own death. On various occasions they formed themselves into military bodies, armed themselves with their husbands’ weapons, rushed into the melée, and turned the doubtful scale of victory.

As long as this bold and independent christian republic occupied their mountain cities, they opposed a formidable obstacle to the insatiable ambition of Ali Pasha; it was, therefore, one of the first of the neighbouring states which he determined to destroy. He made his attempt so early as the year 1792, and its perfidy was the model of all his future proceedings. He invited the Suliotes to a conference on affairs of mutual interest. They descended from their mountain, and, having arrived at the appointed plain below, they laid aside their arms, and engaged in athletic sports and military games, as was usual with them on such friendly occasions. The Pasha, like a tiger from its lair, rushed upon them in this defenceless state, and murdered or captured every man present but three−one of whom escaped, passed up the mountain, and apprised the republic of the treachery. Among the prisoners was the hero Tzavalles, the great leader of the Suliotes. With this man in his power, he endeavoured again to treat with the people. He sent him up the steep, leaving his son behind as a hostage. When arrived at Suli, he exhorted the people to a strenuous defence. He returned a letter to Ali, written in the stern spirit of antiquity: “You think,” said he, “I am a cruel father to sacrifice my child; but if you had succeeded, all my family would have been exterminated without mercy, and no one left to avenge them. My wife is young, and I may have many more children to defend their country; if my boy is not willing to be now sacrificed for it, he is not fit to live, but to die as an unworthy son of Greece.” The enraged Pasha gave orders to ascend, and carry the mountain. While engaged in front, a band of women, headed by the mother of the boy, attacked the Turks in the rear. They were driven down with great slaughter, and Ali himself narrowly escaped.

Though thus defeated, he never abandoned his intention; for a series of years he renewed his attempts both openly and secretly, till at length, having become sovereign of the whole country of Albania, he united the whole of its forces for a final attack on this stubborn rock. More than 40,000 men were leagued round it below, while the defenders above, reduced by various combats, did not amount to 2000. Unsubdued by force, but reduced by famine, they at length agreed to abandon their strong-hold. A safeguard was guaranteed to them, to migrate where they pleased; and the remnant left alive, divided themselves into two bodies, which took different routes through the mountain. They were both attacked and massacred without mercy. The women rushed with their children to the edge of a precipice, where they cast themselves down, and were dashed to pieces, rather than fall into the hands of their loathed conquerors. A few men escaped into a fortress in which was a depôt of ammunition. They were headed by an ecclesiastic, who had distinguished himself by his devoted attachment to the religion and liberty of his country. He here

declared that all resistance was hopeless, and invited the Turks to take possession of this last defence. They eagerly entered, and filled the castle, when the priest applied a match to the powder, and the whole were blown into the air. Among the records of these events, recalling the memory of this brave but exterminated people, is a song by one of the survivors, distinguished by the simplicity but poetic spirit of the original language. The last verse thus comments on the catastrophe

“Now Suli lies low and forlorn−Avaric and Kiaffa renowned,And Kunghi’s high ramparts are torn, its fragments are scattered around:But the gallant Caloyer was there, and he laughed as he lighted the train;Yes, he laughed as he soared in the air, to escape the base conqueror’s chain.”Ali having at length effected this almost hopeless conquest over this free republic, obtained from the Porte the dignified appellation of Aslem or “the lion,” and to commemorate his achievement, he built a splendid seraï on the summit of the mountain, amidst the ruins of the town, which is seen in our illustration peeping over the edge of the precipice. Meanwhile the few survivors of this brave people who had escaped the massacre, fled to Parga and other Christian towns, which afforded them an asylum. They were afterwards enrolled in various corps, and assisted in the liberation of Greece. One of them formed the body-guard of Lord Byron, and were among the mourners that stood round his grave at Missolonghi. But they have now no “local habitation,” and even their name has nearly perished.

SCUTARI AND THE MAIDEN TOWER,

ON THE BOSPHORUS

T. Allom. H. Adlard.

The promontory of Scutari, given in our illustration, was distinguished by the ancient Greeks under the name of ακρον βοος, or “cape of the ox,” because it was supposed to be that to which Iö swam, when, under the shape of that animal, she fled from the persecutions of Juno, and gave the name of Bosphorus to the whole streight. Under the Greeks of the Lower Empire it was named μεγα μετωπον, or “the great forehead,” from its bold projection into the sea. It is strikingly picturesque. Just below it is the turbulent estuary, formed by the rushing waters of the streight, opposed by those of the Sea of Marmora, where, in the calmest day, they wheel and boil among the rocks with a turbulence and agitation quite extraordinary in the still and placid surface of the water around them. Rising from hence, the promontory displays a succession of picturesque objects, clothing its surface−kiosks, and grottos, and thickets, and hanging gardens−till they ascend to the summit, crowned with the dome and minarets of a mosque, and the noble barracks of Scutari.

This place was distinguished as the scene of blood, in the terrible commotions that preceded the final suppression of the Janissaries. A body of those fierce and mutinous soldiers passed the Bosphorus, and made an attack on the Barrack of Scutari, hoping to convert the extensive edifice into a fortress, to overawe the opposite city from this eminence. They were repulsed, however, after much carnage, by the cannon of the topgees, and dispersed in two bodies: one took the route along the coast to Moudania; another proceeded in the opposite direction, up the Bosphorus, which they recrossed, and established themselves among the woods of Belgrade, where they became a desperate banditti, and carried their depredations to the walls of the capital. It was found impossible to dislodge them in the ordinary way from the dense forest, and the whole was set on fire. The vast surface of timber blazed up, so as to illumine the dark waters of the Black Sea with its glare; and the banditti, driven from its recesses, were shot without mercy, with boars, wolves, and other beasts of prey, as they issued from the burning cover. When the fire subsided, the whole district exhibited a melancholy spectacle of Turkish destruction−vast forest-trees prostrate and half consumed, lying among the scorched bodies of men and various animals.

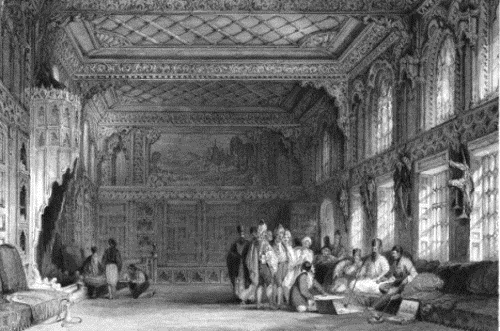

GOVERNOR’S HOUSE, PHILADELPHIA.

ASIA MINOR

T. Allom. W. Topham.

Philadelphia is one of the churches of the Apocalypse, which retains some traces of its former prosperity. The seraï, or palace of the muzzelim, as the governors of the towns in Asia Minor are named, is a spacious and sumptuous edifice, and the interior is decorated with those displays of Turkish magnificence that befits the magistrate who presides over a large and populous town. When a Frank traveller passes through an Oriental city, it is not sufficient in general to show his firman by his janissary, but the muzzelim expects to be personally waited on, and, after he has treated his guest with the usual refreshments of coffee and a chiboque, he inquires his business. It is impossible to make a Turk comprehend the usual objects of European travelling in the East, no more than to communicate to him the feeling of a sixth sense. He cannot conceive why a man should break in upon the sleepy repose of a dozing life, and fatigue himself by climbing mountains and exploring caverns, which can yield him no profit. The only motive of which he can have any distinct comprehension is that which leads a man to explore ruins; for every Turk is impressed with a notion that the ancients abounded in wealth, and that in the edifices they left behind them, a man could find an urn of gold under every stone, if he knew how to search for it, and this knowledge he believes the superior intelligence of every Frank imparts to him. The janissary, therefore, who attends a traveller, though perfectly indifferent in other places, is always on the alert among ruins. He watches him eagerly when he is trying to read an inscription, certain that it points out a concealed treasure which the traveller will immediately discover.

Our illustration represents a scene of this kind. The ingenious artist has depicted himself sitting on the divan of Chem Bey, the muzzelim of Philadelphia, to whom he is exhibiting his sketches. In these latter times even Turks have made some advances in knowledge, and the present muzzelim took an interest in such things, which former travellers could not excite in one of the old school.

THE GYGEAN LAKE, AND PLACE OF A THOUSAND TOMBS.

ASIA MINOR

T. Allom. S. Fisher.

The name of Gyges is distinguished in the ancient history of this region. Candaules, king of Lydia, had wedded a most beautiful wife; but not content, says the historian, with the private enjoyment of her charms, he was anxious that others should witness his felicity, so he exposed her to his friends. Among the rest, Gyges was admitted to this happiness, and the consequence was such as might be expected from his folly. Gyges became enamoured of the wife of his imprudent friend; and the lady, indignant at the treatment she received, encouraged him. By means of a ring which rendered him invisible, he gained access to the secret chambers of the palace, slew Candaules, married his queen, and succeeded to the kingdom of Lydia.

About five miles from Sardis, the capital of Lydia, is the Gygea, a large lake so called probably from the memorable king. It stands not far from the Hermus, and was supposed to be an artificial excavation, formed to draw off the waters of the river, and to avert the consequence of its inundations. In the course of ages it has assumed the character of a magnificent solitary lake, of nature’s own formation, though in several places mounds and ramparts are still discernible, and seem rather thrown up to prevent the overflowing of the lake, than as part of its original construction. The lake, as it now exists, is of considerable extent; the rich mould on its banks, of a muddy consistence, exuberant in reeds, and abundance of such aquatic and palustric plants as love such a soil. The water, in colour and transparency, resembles that of a common pond, and seems alive with fish. Another circumstance marks it−flocks of swans and cygnets hover above the surface, and flights of various aquatic birds darken the air. Among them myriads of gnats buzz about, and, like those of Myus are the terror and torment of those who approach the lake. But the circumstance which renders this place so interesting is, that the shores of this solitary sheet of water, were selected by the ancient kings of Lydia, as an appropriate spot for their last resting-place. It is a vast cemetery, in which the regal remains were deposited, and the multitude of monuments that still exist, has acquired for it the name of “the Place of a Thousand Tombs.” The general appearance of these tombs is that of large grass-grown tumuli: swelling from the surface are verdant hillocks of a conical form, of various sizes, and somewhat resembling the larger ones seen on the plains of Troy and Roumelia. But there is one among them of distinguished form, and remarkable for many circumstances connected with it. It is that of Alyattes, the father of Crœsus. The means by which it was erected display a sad picture of the depravity of Lydian manners, and forms a sequel to the story of Gyges. The number and wealth of the girls of bad fame in Sardis were so great, that they raised, at their own expense, assisted by some of the lower classes, this magnificent tomb of their king, and monument of their own infamy. The remains of it at the present day, exactly correspond with the description of Herodotus, who saw and described it nearly five hundred years before the Christian era. The base of masonry still traceable, extends for six stadia or three-quarters of a mile. The superstructure on this is a truncated cone, now covered, like the rest, with grass very rich and verdant. On ascending the summit, a singular and characteristic view presents itself. Round its base are the smaller monuments, extending in various directions. From thence the still and placid surface of the lake spreads itself, penetrating into many solitary recesses, as if avoiding human research, and in perfect keeping with a place intended for the repose of the dead. What adds to the deep interest excited by this venerable relic of antiquity, is, that its origin and history is of undoubted authority. The traveller who visits it sees a monument as vast and ancient as a pyramid of Egypt, but whose history is much more certain and authentic.

Our illustration presents the perfect character of this place: the solitary stillness of the lake−the luxuriance of its aquatic vegetation−the vast flocks of its feathered inhabitants−its conical tombs appearing over the neighbouring elevations, and marking the cemetery in which the remote kings of Lydia slumber in solitary magnificence.

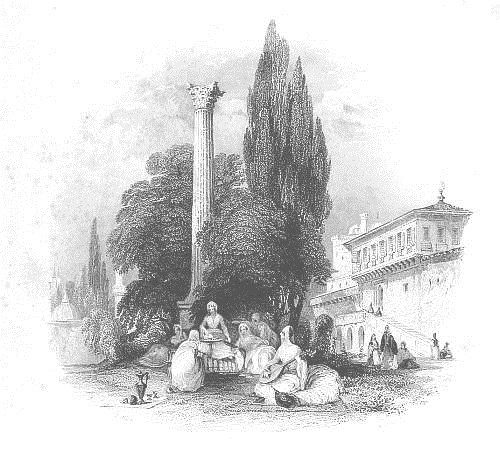

GARDENS OF THE SERAGLIO.

CONSTANTINOPLE

An error has long and universally prevailed in western Europe, as to the degree of liberty which Turkish ladies enjoy, and their supposed subjection to their husbands has excited the pity of Christian wives; but, if freedom alone constitute happiness, then are not only the wives and the odaliques, but the female slaves in Turkey, the happiest of the human race. They visit and are visited without exciting jealousy, or being subjected to resentment; the most gorgeous apartments, the most beautiful pleasure grounds of every palace, are devoted solely to their use; and the gardens of the seraglio at Constantinople, with their orange groves, rose beds, geraniums, and marble fountains, afford an admirable illustration of some scene of enchantment in an Arabian tale.

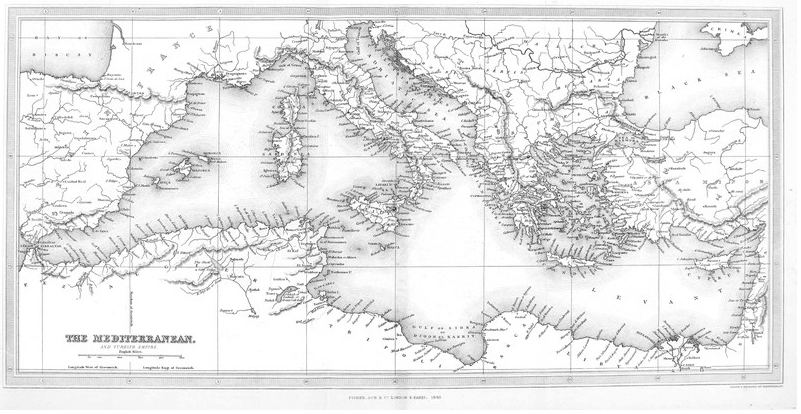

THE MEDITERRANEAN AND TURKISH EMPIRE

FINIS

1

The word Islam is mentioned in the Koran as, “the true faith.” It signifies, literally, “resignation.” A professor of it is called Moslem, and, in the plural number, Moslemûna, which is corrupted, by us, into “Mussulman.”

2

He was lame of one leg, and hence called Demur lenk, which we have corrupted into Tamerlane.

3

The origin of this word is a subject of controversy. Some suppose it derived from the Greek εις την πολιν, eis tēn polin, which they used when going to the capitol. It is, with more probability, a simple corruption of the former name. The barbarians who pronounce Nicomedia, Ismid, would be likely, in their imperfect imitation of sounds, to call Constantinople, Stambool.

4

The fondness of the Turks for flowers was remarked by Busbequius, in his embassy to Soliman the Magnificent, a century before−Turcæ flores valde excolunt. Busb. p. 47. He notices the tulip as a flower new to him, and peculiar to the Turks.

5

It is, however, more generally supposed that Olympus in Thessaly and Macedon is that designated by Homer.

6

Exod. xxiv. 4. Joshua iv. 3.

7

As it may be agreeable to some of our readers to know how to make this ancient food, the following is the mode pursued by the Turks:−A quart of boiled milk is poured upon barm of beer, and allowed to ferment. Of this fermentation two spoonsful are poured into another quart of milk. When this process is repeated, the flavour of barm is altogether lost. The yaourt thus made becomes the substance which forms the future food without more barm. A tea-spoonful is bruised in a vessel, and a quart of tepid fresh milk is poured upon it, and set aside in an earthen vessel: in two hours it will be a rich, thick, subacid fluid, covered with a coat of cream.

8

It is supposed the Hummums in Covent Garden, whose etymology has puzzled so many, were so called from the warm-baths they contain, first introduced from Turkey.

9

To this the Greek girls form an exception. Refined by education, strongly attached to their families, and abhorrent to slavery, their natural vivacity is overcome by their state, and they appear sad and dejected amid the levity that surrounds them.

10

This practice is resorted to on other occasions. When any article is dropped into the water too minute to be discovered by the eye above, or dragged for, a small quantity of oil is thrown upon the surface, and rings and other trinkets have thus been recovered in a depth of ten or twelve feet of water.

11

“Les Grecs appellent Saint Jean Ayos Seologos an lieu d’Agios Theologus, le Saint Theologien, parce qu’ils prononcent le theta comme un sigma.”—Tournefort.

12

Horologia in publico haberent nondum adduci potuerunt.—Busbeq.

13

Caravan Seraï, the “Merchants’ Palace.”

14

Rev ii. 15.

15

Acts vi. 5.

16

1 Tim. vi. 20.

17

The towns are designated in the following hexameter:

“Smyrna, Rhodos, Colophon, Salamis, Chios, Argos, Athenæ.”

18

Cette porte dont l’empire Ottomane a pris nom.—Tourn.

19

Some say it was to Magnesia on the Meander.

20

Magnesia ad Sipylum, a qua magnes lapis, ferum attractens, nomen sortitus est.

21

The names were as follow: Proté, because it is the first met in sailing from, Constantinople−Chalki, from its copper mines−Prinkipo, the residence of a princess−Antigone, so called by Demetrius Polyorcetes in memory of his father Antigonus−Oxy, from its sharp precipices−Platy from its flatness−Pitya, from its pines, &c.

22

The gum-resin, yielded by these plants, is sometimes collected by combing the beards of the goals, which browse among them, when they return home at night; and sometimes a leather thong is drawn across them, and that which adheres scraped off. The boots of those who walk through the shrubs are often incrusted with this gum.

23

Jerem. vii. 7.

24

Psalm civ. 17.

25

There is another bridge of considerable extent called Buyuk Tchekmadgé, thrown across an arm of the sea some miles from the capital.

26

Rev. iii. 15.

27

Ep. to Colos. iv. 16.