Полная версия

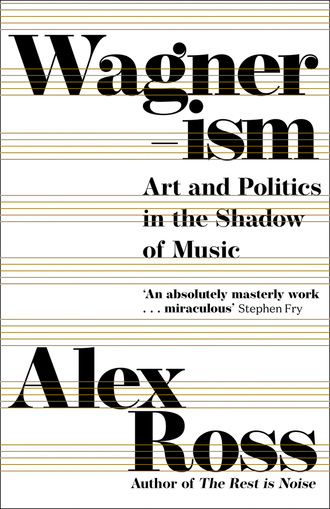

Wagnerism

“Endless melody” proved to be another inescapable Wagner formula. It stands in seeming contrast—almost in contradiction—to the leitmotif, which entered common parlance after the premiere of the Ring. Leitmotifs are crisply defined melodic fragments that play a signifying role; endless melody suggests a continuous, formless flow of consciousness. As the German musicologist Carl Dahlhaus once showed, the two concepts are really complementary. Endless melody consists, in essence, of leitmotivic materials seamlessly interlocking.

In March 1860, Napoleon III commanded a performance of Tannhäuser at the Opéra. The historian Gerald Turbow diagrams the politics behind the move: the emperor wished to improve relations with Austria, and Princess Pauline von Metternich, the wife of the Austrian ambassador, was a Wagner champion. At the same time, the gesture seemed intended to win allies among domestic progressives. In a similar liberalizing spirit, Napoleon III would sponsor the 1863 Salon des Refusés, giving his imprimatur to Édouard Manet, James McNeill Whistler, and other painters rejected by the Académie. In the end, the entire scheme backfired. Some leftists who had seen Wagner as a revolutionary stalwart now looked at him askance. The legitimists had even less reason to approve of him. When Tannhäuser finally opened, on March 13, 1861, much of the audience was predisposed to dislike it.

The opera was already more than fifteen years old—a landmark of Wagner’s early development rather than a harbinger of his mature style. In his first four operas, he had tried his hand at various genres. Die Feen is a Romantic fantasy; Das Liebesverbot is an Italianate treatment of Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure; Rienzi is a grand opera in French style; The Flying Dutchman returns to the Romantic supernatural. Tannhäuser, based on a medieval legend that Wagner probably first encountered by way of a retelling by Heinrich Heine, attempts a synthesis, incorporating grand-opera and bel canto features in a German Romantic frame. Wagner was never altogether satisfied with the result, and for the Paris production he extensively reworked the score.

Baudelaire summarized the story thus: “Tannhäuser represents the struggle between two principles that have chosen the human heart for their chief battlefield: that is to say, flesh and spirit, hell and heaven, Satan and God.” The title character is torn between the debauchery of the goddess Venus, who tempts him into the mountain grotto of the Venusberg, and the more wholesome adoration of Elisabeth, the niece of the Landgrave of Thuringia. The eventual self-sacrificial death of Elisabeth brings about Tannhäuser’s redemption, as the hero escapes Venus’s clutches. Many of the opera’s principal motifs are given a lavish presentation in the overture. The “furious song of the flesh,” as Baudelaire heard it, fails to vanquish the stately Pilgrims’ Chorus: the two elements are intertwined and reconciled.

When Wagner revised Tannhäuser for the Opéra, he gave special attention to the opening scene, in which nymphs, bacchantes, and other revelers enact the Venusberg. With an injection of the advanced harmonic language of Tristan, the sequence turns into a matchless orgiastic frenzy. Wagner hoped that the new material would solve an imminent crowd-control problem. Paris audiences were accustomed to seeing a ballet scene not at the beginning of an opera but in the second act. The noblemen of the Jockey Club, who occupied many of the most prominent boxes, were in the habit of skipping the first act, arriving in time to see their favorite ballerinas. Although Wagner refused to supply a ballet in the expected place, he thought that his supercharged Venusberg music and the accompanying dancing would astound everyone into surrender.

He miscalculated, to say the least. The Jockeys, who had ties to the legitimist camp and no great love for Napoleon III, had already decided to ruin the show. They came equipped with hunting whistles and made a mighty noise. The entrance onstage of ten hunting dogs, loaned by the emperor, caused merriment, eliciting cries of “Bravo les chiens! Bis les chiens!” The Wagnerites fought back, shouting, “À bas les Jockeys!” Fistfights broke out; Princess Metternich attempted to confiscate the Jockeys’ noisemakers. At the second performance, the din grew so loud that Nina de Callias, the model for Manet’s Lady with Fans, compared it to the sound of a dozen locomotives. In the end, Tannhäuser seemed to have won over most of the public. But Wagner had had enough. After one more tempestuous performance, he withdrew the work in a fit of pique. The Opéra did not touch his music for another thirty years.

Paris had witnessed such scenes before, and more were to follow. In 1830, at the premiere of Victor Hugo’s Hernani, the eighteen-year-old Gautier had shouted on behalf of the new Romanticism. The most crucial phase of such aesthetic battles took place not during the performance but afterward in the press. In the case of Tannhäuser, the conservatives almost immediately lost the argument. As the musicologist Annegret Fauser notes, Wagner and his allies successfully characterized the opposition as a convocation of imbeciles who were blocking progress. The most effective broadside appeared on April 1, 1861, in the Revue européenne: an eleven-thousand-word article titled “Richard Wagner,” by Charles Baudelaire.

BAUDELAIRE

Baudelaire, 1863

Eight years younger than Wagner, Baudelaire could hardly have been more different in personality. While the composer came from relatively humble origins, the poet grew up in comfortable bourgeois circumstances, and assumed, with a certain pride, a downward trajectory. Where Wagner refrained from most bohemian habits, Baudelaire indulged in absinthe, opium, hashish, and large quantities of wine. Wagner’s love affairs often stopped short of sexual congress; Baudelaire’s early and frequent encounters with prostitutes probably gave him the venereal disease that has been linked to his early death. Wagner never lost faith in an ever-evolving conception of God; Baudelaire hailed Satan. Wagner gazed backward to mythic origins; Baudelaire opened his poetry to the seamiest tendencies of contemporary life. Even so, the poet’s identification with the composer was profound. Having endured his own scandal on account of Les Fleurs du mal, Baudelaire saw the same forces of philistinism conspiring against Tannhäuser.

Listening to Wagner’s music and reading his texts, Baudelaire felt repeated shocks of familiarity. Both men relied on the rhetoric of the new. “Children! make something new!” was one of Wagner’s slogans; for Baudelaire, it was “To the bottom of the Unknown to find the new!” Both sympathized with wanderers and outcasts. Venus flits through Fleurs, which critics have divided into cycles of the “black Venus,” the “white Venus,” and the “green-eyed Venus.” The poet who contrasted muses and Madonnas with temptresses and whores was well prepared for the Elisabeth-Venus duality of Tannhäuser. On the purely musical level, Wagner’s investigation of unusual harmonies and timbres accorded with Baudelaire’s ideas about the beauty of the ugly and the bizarre. Berlioz had accused Wagner of making the horrible beautiful and the beautiful horrible. Baudelaire might have loved the music for exactly this reason.

Although Baudelaire had warmed to Wagner as early as 1849, he was unprepared for the impact of the Théâtre-Italien concerts. His mania on the subject amused his friends, as he told his publisher: “I dare not speak more about Wagner; I’m getting mocked too much. That music has been one of the great pleasures of my life; it has been easily fifteen years since I have felt such ravishment.” The following day, Baudelaire sent a letter to the composer, characterizing his experience as one of addiction, infatuation, subjugation. Indeed, he metaphorically placed himself in a passive sexual role:

Before everything, I wish to tell you that I owe to you the greatest musical pleasure I have ever experienced … It seemed to me that this music was mine, and I recognized it as every man recognizes the things he is destined to love … I often experienced a sensation of a rather bizarre nature, and this was the pride and pleasure of comprehending, of letting myself be penetrated and invaded, a truly sensual enjoyment, which resembles that of rising in the air or tossing on the sea.

Some artists might have been alarmed to receive such a piece of correspondence, but Wagner was delighted. In his autobiography, he reports the satisfaction of encountering this “extraordinary mind,” which expressed itself “with conscious boldness in the most bizarre flights of fantasy.” Despite the lack of a return address—Baudelaire had not given one, to avoid the impression he was asking for a favor—Wagner tracked down the poet and invited him to his salon. Baudelaire set to work on his essay, steadily expanding its scope over many months. “I dream continuously of WAGNER and POE,” he wrote to his publisher. Only in the wake of the Tannhäuser debacle did the article finally appear in print. It was subsequently republished under the title “Richard Wagner et Tannhäuser à Paris.”

Baudelaire begins in medias res, in the manner of Poe: “I propose, with the reader’s permission, to go back some thirteen months, to the beginning of the affair.” There follows a withering précis of the Parisian battle over Wagner, which erupted before anyone had had a chance to hear the music. The poet then tells of his own conversion experience. The prelude to Lohengrin struck him most strongly. Reproducing passages from Wagner’s program note, which describes the apparition of the Holy Grail to a “pious wanderer,” Baudelaire italicizes particular phrases: “plunges into an infinity of space,” “he yields to a growing feeling of bliss,” “radiant vision,” “he is swallowed up in an ecstasy of adoration, as if the whole world has suddenly disappeared,” “burning flames gradually mitigate their brilliance,” “into whose hearts the divine essence has flowed,” “into the infinities of space.” He then summarizes his own impressions, stressing the overlap with Wagner’s text:

I remember that from the very first bars I suffered one of those happy impressions that almost all imaginative men have known, through dreams, in sleep. I felt myself released from the bonds of gravity, and I rediscovered in memory that extraordinary thrill of pleasure which dwells in high places … Next I found myself imagining the delicious state of a man in the grip of a profound reverie, in an absolute solitude, a solitude with an immense horizon and a wide diffusion of light; an immensity with no other decor but itself. Soon I experienced the sensation of a brightness more vivid, an intensity of light growing so swiftly that not all the nuances provided by the dictionary would be sufficient to express this ever-renewing increase of incandescence and heat. Then I came to the full conception of the idea of a soul moving about in a luminous medium, of an ecstasy composed of knowledge and joy, hovering high above the natural world.

The convergence of these associations, which also resemble phrases from Liszt’s essay on Lohengrin, proves to Baudelaire that “true music evokes analogous ideas in different brains,” that verbal images and musical ones are intimately interrelated. They reflect the “complex and indivisible totality” of God’s creation. To illustrate the point, Baudelaire inserts, without naming the source, eight lines from his own poem “Correspondances,” published in the first edition of Les Fleurs du mal:

Nature is a temple where living pillars

Let fall at times a confusion of words;

There man passes through forests of symbols

Which look at him with knowing eyes.

Like long echoes that distantly lose themselves

In a shadowy and profound oneness,

As vast as night, as vast as light,

Scents, colors, and sounds answer each other.

Baudelaire thus delineates a correspondence between Wagner’s goal of reunifying the arts and the poet’s own synesthetic command of smell, sight, and sound. The forest imagery deepens the identification: George Sand had questioned Wagner’s assumption that only Germans could understand the enchanted woods of Der Freischütz, and now Baudelaire places himself in similar terrain, the mystery only heightened by the incomparably spooky vision of symbols with eyes.

As he confesses in his introductory letter—“From the day I heard your music, I have said to myself constantly, especially at bad hours: If only I could hear a little Wagner tonight!”—Baudelaire is responding with the ardor of an addict, an opium dreamer. Wagner’s revolutionary politics leave him cold; the adventures of 1848 and 1849 are an “error excusable in a sensitive and excessively nervous mind.” What matters is the composer’s “absolute, despotic taste for a dramatic ideal.” Baudelaire proceeds to quote Wagner’s “Lettre sur la musique,” which describes myth’s capacity to activate powers beneath conscious reason: “The character of the scene and the tone of the legend work together to throw the mind into that dream-state where it is soon brought to the point of full clairvoyance, and it discovers a new interrelationship of the phenomena of the world, which the eyes could not perceive in the ordinary waking state.”

Delving into the Tannhäuser overture, Baudelaire predictably favors the profane over the sacred. The world of Venus exudes “languors, fevered and agonized delights, ceaseless returns towards an ecstasy of pleasure which promises to quench, but never does quench, thirst … the whole onomatopoeic dictionary of Love.” Indeed, Baudelaire upends the moral scheme of the opera by claiming that the Venusberg music represents “the overflowing of a vigorous nature, pouring into Evil all the energies which should rightly go to the cultivation of Good; it is love unbridled, immense, chaotic, raised to the level of a counter-religion, a satanic religion.”

The extravagant vocabulary of the essay’s concluding section foreshadows Nietzsche’s Dionysian aesthetics. Indeed, Baudelaire comes close to preempting the Übermensch when he says that Wagner’s passion “adds to everything a je ne sais quoi of the superhuman.” One should exult in “these excesses of vigor, these overflowings of the will, which write themselves on works of art like flaming lava on the slopes of a volcano, and which in ordinary life often mark that delicious phase that follows upon a great moral or physical crisis.” This superman is not, however, a specifically German quantity. Indeed, Baudelaire ignores Wagner’s Germanness and instead criticizes the chauvinistic small-mindedness that has led French crowds to thwart a work of high importance. In an epilogue that he added for the book version of the essay, he asked, “What is Europe going to think of us, and what will they say about Paris in Germany?”

In the end, this apparent submission to Wagner is a wholesale reinvention of him. As the philosopher Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe puts it in his study Musica Ficta (Figures of Wagner), Baudelaire wards off music’s threatened dominance by way of “subjective reappropriation.” Music remains stubbornly inarticulate, even in Wagner’s word-heavy, emotionally charged incarnation. Baudelaire’s declaration that the music “returned me to myself” stealthily reclaims territory that he had seemingly given up in his state of abject wonder. “I myself am the world,” the lovers sing in Tristan, the opera that Baudelaire never heard. By saying, in effect, “I myself am Wagner,” Baudelaire makes the music his own, and forever changes how the world perceives it. In this agon, the one who surrenders is the victor.

Wagner’s initial reply to the Tannhäuser essay alludes offhandedly to Baudelaire’s “very beautiful” words before retailing the usual stories of his woes. Perhaps he only skimmed it, for in a second letter he suddenly sounds almost desperate with gratitude. He has tried several times to call on Baudelaire in order to convey his appreciation for the article, “which honors and encourages me more than anything that has ever been said about my poor talent.” Wagner goes on, in passable French: “Would it not be possible to tell you soon, out loud, how intoxicated I felt upon reading these beautiful pages, which related to me—as does the best poem—the impressions I must boast of having produced on a sensibility as superior as yours? A thousand thanks for this blessing you have given me, and believe me proud to call you a friend.” Baudelaire reported that Wagner later hugged him, saying, “I would never have believed that a French writer could so easily understand so many things.” Did Wagner like the essay that much? Or did he realize that its unorthodox speculations granted him a kind of exegetic immortality?

When “Richard Wagner” was published, Baudelaire had only six years to live. Symptoms of physical and mental decline soon became evident. In 1866, the poet suffered a massive stroke, and spent his final year in a nursing home, incapacitated and effectively unable to speak. Among his regular visitors were Suzanne Manet, the wife of the painter, and the pianist Eléonore-Palmyre Meurice. Both women played Wagner for the invalid. Another friend recalled: “When I spoke of Wagner and Manet, he smiled with happiness.”

In 1888, Nietzsche came across Baudelaire’s Œuvres posthumes, which recounted the poet’s last days and quoted Wagner’s appreciative letter of 1861. The only other time the composer ever waxed so effusive, Nietzsche claimed, was when he read The Birth of Tragedy. Baudelaire’s writings show Wagner to be a cosmopolitan, supra-German artist; at the same time, they point up his decadence, his appeal to sick souls. Nietzsche observes that when Baudelaire was “half mad and slowly going under, they applied Wagner’s music to him as medicine.” Within a year, Nietzsche had himself passed into the beyond, playing his Wagnerian fantasies at the piano.

AXEL’S CASTLE

The Wagner wars raged on. In October 1861, a few months after the Tannhäuser scandal, the conductor Jules Pasdeloup instituted a series of low-priced Concerts Populaires in the Cirque Napoléon, now the Cirque d’Hiver, a circular arena that at the time could seat around five thousand people. The following year, Pasdeloup programmed an excerpt from Tannhäuser, and added more Wagner as the decade went on. The conductor also led an extended run of performances of Rienzi in 1869 and 1870. A decade later, John Singer Sargent painted Pasdeloup’s orchestra in rehearsal—a moody tableau of blurry black-clad figures set against white score pages and golden brass.

Paul Verlaine was a regular at the Cirque, arriving early to be assured of a good seat. In his Épigrammes, the poet remembers that he had “thrown a punch / For Wagner” in the skirmishes that regularly took place between fans and detractors. Isidore Ducasse, the short-lived proto-Surrealist author who wrote as the Comte de Lautréamont, also had Wagnerite leanings. In the second canto of Les Chants de Maldoror, the testament of an apostle of evil, the figure of Lohengrin is seen hurrying down a city street in an anonymous modern guise. Maldoror is tempted to stab him to death, so that the beautiful youth will not “become like other men,” but he restrains himself. “I am yours,” he says. “I belong to you, I no longer live for myself.”

Émile Zola and Paul Cézanne, schoolboy friends from Aix-en-Provence, belonged to the local Wagner Society and joined the ranks of the Wagnerians at the Cirque on moving to Paris. Zola boasted that he had been among the first to shout “Bis!” (“Encore!”). Later, having renounced Impressionism in favor of naturalism, he looked back on those adventurous years with a less sentimental eye. Claude Lantier, the failed, doomed painter at the heart of Zola’s 1886 novel L’Œuvre, is modeled on Cézanne. Among the cast of supporting characters is a painter named Gustave Gagnière, whose soliloquies preserve some of the more unhinged Wagnerite rhetoric of the period:

Oh! Wagner, the god, in whom centuries of music are incarnated! His work is the mighty ark, all the arts in one, the true humanity of the characters finally achieving expression, the orchestra separately experiencing the life of the drama; and what a massacre of conventions, of inept formulas! what a revolutionary emancipation into the infinite! … The overture to Tannhäuser, ah! it is the sublime hallelujah of the new epoch …

Gagnière defies the hissing ignoramuses at the Cirque and exits one concert with a black eye.

Baudelaire was not the only French author to develop a distinctive vocabulary for Wagner. Another influential advocate was the arch-bohemian writer and critic Champfleury, the nom de plume of Jules Fleury-Husson—a “juggler, a thermometer of enthusiasms,” according to the art historian T. J. Clark. While Baudelaire mulled over his Wagner essay for more than a year, the prolific Champfleury dashed off an aphoristic, free-associating pamphlet a few days after the first Théâtre-Italien concert. Seeking “analogies of sensations” to capture the experience, Champfleury first evokes the infinite expanse of the ocean, then looks toward the forest, which had already made a memorable appearance in Baudelaire’s “Correspondances.” He writes: “There is a religious aspect in the work of Wagner, the religious feeling that you experience in a thick forest, when you traverse it in silence. Then the passions of civilization fall away one by one: the spirit leaves the little cardboard box where it is habitually locked away whenever one ventures out to a soirée, to the theater, in society; it purifies itself, it visibly grows, it breathes contentedly and seems to climb to the tops of tall trees.”

Champfleury’s essay was published in March 1860. Wagner, buffeted by attacks in the French press, gratefully seized on it and folded some of its images into his “Lettre sur la musique.” According to Champfleury, the music is in no way bereft of melody, as conservative critics complain; rather, it is “only one vast melody,” indivisible like the sea. Wagner’s “Lettre,” in turn, takes up the formula of the “endless melody” and spins its own extended forest metaphor, asking the reader to imagine a lonely traveler who, on a summer evening, leaves behind the noise of the city and goes walking in a beautiful forest. There, he listens to the “endless diversity of voices awakening in the wood” and has the “perception of a silence becoming ever more eloquent.” These sounds cannot be separated from one another; they are “but one great forest-melody,” religious in character.Wagner is thinking, no doubt, of the shimmering Forest Murmurs music in Act II of Siegfried. The influence is circular: forest imagery first appears in Baudelaire and then reappears in Champfleury’s ode to Wagner, which Wagner absorbs in turn. No wonder Baudelaire felt a sense of self-recognition on reading the “Lettre.”

Wagner, in his youth, had perplexed George Sand with his assertion that French listeners would never be able to penetrate the forests of German folklore. The rising generation of French writers might have led him to rethink his position, if anyone had thought to challenge it. Deep in the Black Forest, a symbol-encrusted magic castle was about to rise, the creation of a stupendous character who could make even Wagner wish for a little peace: Jean-Marie-Mathias-Philippe-Auguste, Comte de Villiers de l’Isle-Adam.