Полная версия

Beautiful Affair

THE STINGER

It was in McGann’s pub in 1976 where myself and cousin Paul discovered the joys and tribulations of alcohol. I was reared in a teetotal house, so the only time we ever saw whiskey was at Christmas, when in the name of a festive welcome, Dad unwittingly attempted to poison guest after guest with tumblers filled to the brim. It took deft skill to get glass to mouth. In Doolin I tasted stout, beer, lager, shorts and all sorts of fancy drinks, all for the first time. Steve Birge, a friend of Tommy’s from Vermont, introduced us to his list of exotic American cocktails, including the Sombrero, a mix of Kahlua, crushed ice and fresh milk, and the Killer Stinger, a potent mix of brandy and crème de menthe poured into a glass of crushed ice. The Doolin twist was to crush the ice by taking a tea towel full of it and battering it against a wall. Paul and I settled on the Stinger as our drink of choice, and I can safely say it is firmly etched in our hangover memory.

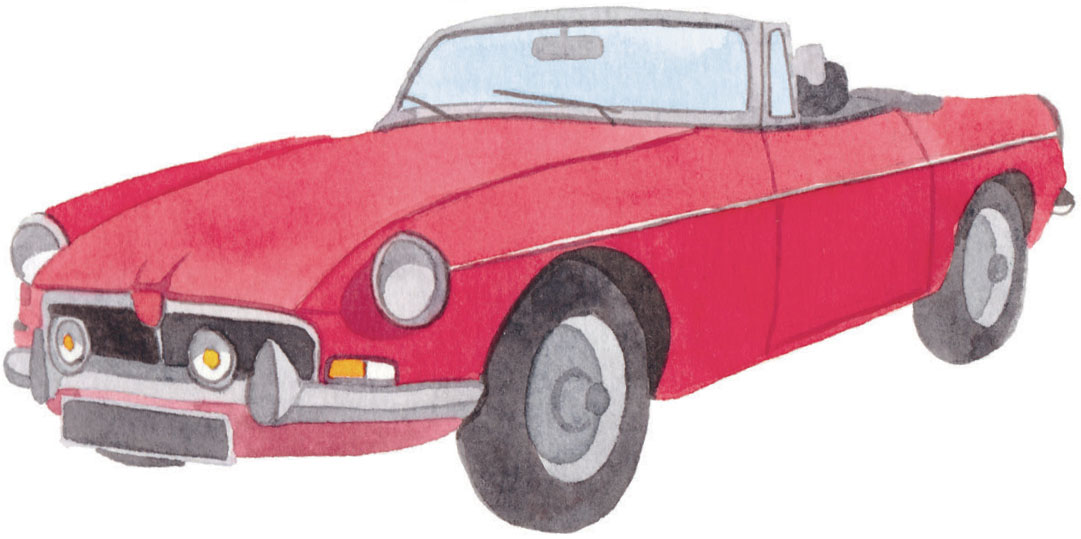

THE MG

Somewhere in a mounted collage I recognise the old pub MG convertible, and I’m right back in the driver’s seat accompanied by concertina ace Noel Hill, on our way back from Garrihy’s shop with the morning supply of milk and eggs. I had never driven a car before that summer, so the excitement was palpable every time I turned the key. On our way back down the hill towards the pub, a tractor suddenly appeared around the corner. In a fit of panic, I swerved to avoid it but ended up sideways in the ditch with the wheels spinning in the air. The farmer was highly amused as he tied a rope to the car and brought the MG back onto the dirt road, bidding us well on the rest of our journey. As we continued on down, we noticed a group of people gathered outside the pub pointing in our direction. The village wire service had notified base of our little escapade, and as we rounded the rear of the pub some of the lads guided us into our parking spot like a Formula 1 pit signals team. ‘Well done, lads. Emerson Fittipaldi called there, looking for yer details!’ shouted one. ‘I hear Evel Knievel is gonna jump the Grand Canyon, boys – sure ye might have a go at the Cliffs!’ laughed another. For days, we heard nothing else, and all the locals made sure we were never going to forget how we were run off the road by a tractor – chugging its way UP a hill. Years later, at the Irish Embassy pub in Boston, Tommy introduced me to a TV host friend whose first words were, ‘I’ve heard a lot about you. Tommy tells me you could have made it in Formula One. We could set you up for Nascar while you’re here – or maybe you’d prefer the demolition derby?’

THE ORIGINS OF ‘BEAUTIFUL AFFAIR’

There comes a time when you look around

And you see the ocean rise before your eyes, showing no surprise.

So you make your way down to the shore,

And you climb aboard and give yourself a smile, it makes you feel alive.

– ‘Beautiful Affair’, Light in the Western Sky (1982)

The imagery of ‘Beautiful Affair’ is Doolin and neighbouring Lahinch, where I spent many Sundays of my youth on the sprawling beach and sandy dunes, playing on chair-o-planes and dodgem cars and swimming in the wild Atlantic Ocean.

Today as I sit in my old haunt, I think I finally understand the song it gave to me. I certainly know more than that seventeen-year-old boy who arrived at his first major crossroads not really sure which direction to take. Whatever road he chose, it was guaranteed to turn upside down his sheltered and wonderful childhood – but it was time. Nights were now filled with the dreams I would often realise the following day, as I played music, sang my songs and discovered writers, philosophers and poets.

I close my eyes and summon the spirits of the music to fill each crack and crevice with their wonderful tunes and laughter – I can hear the notes bounce from hand to bow, feet firmly stomping out the beat as tourists and travellers alike are drenched in the atmosphere of the moment. I see postcard snippets of the world flutter before me: I see Rome, Amsterdam, Sydney, Boston, Calgary, all the smaller towns and villages and those wonderful faces who embraced and cheered the Wing’s effervescent musical swagger. It all began here in this room at McGann’s Pub in Doolin – the place where I belong.

CHAPTER 3

MAURA O’CONNELL

Mell and Colly lay down by the water to watch the stars collide.

He takes her by the hand, says

‘I can’t understand this fear we keep inside.

Take a look along that empty shore.

If we walk that lonely road

I’ll pick you up when you fall down.

You’ll be there when I fall down.’

– ‘From the Blue’, What You Know (2002)

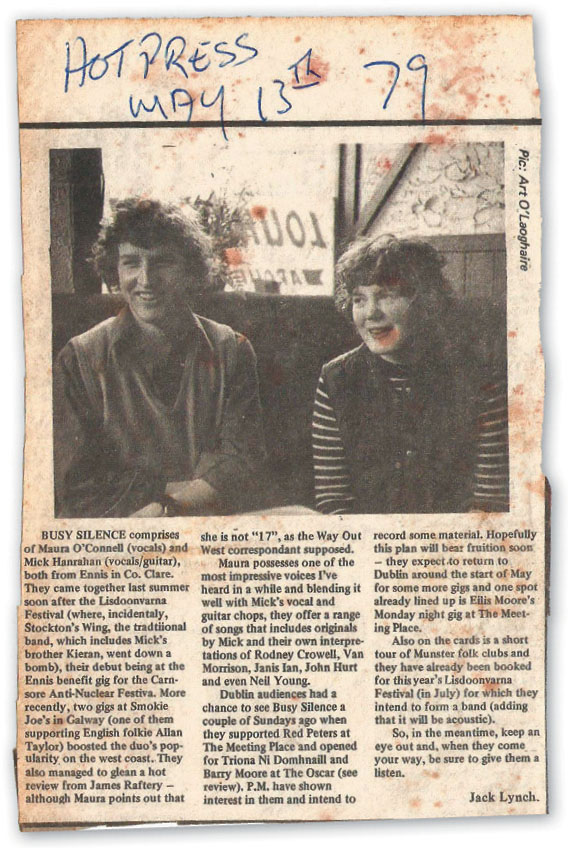

By 1977 I was writing a lot, singing at sessions and playing the odd support gig. As with all gigs, it helps to have a professional in your corner; at a Clive Collins Hobo Junction gig, I met up with local sound engineer TV Honan, whom I’d first met in our teens at the Friary Hall Youth Club. TV (Thomas Vincent, in case you were wondering) was meticulous in his efforts to ensure I had a good sound. This was all new to me, as in my younger days, sound engineers rarely acknowledged our band’s presence, let alone offered a sound check.

TV called a few weeks later, suggesting I should hook up with Maura O’Connell for a few songs. I knew Maura from the family fish shop in Ennis right across the street from where I worked as a teenager, and I heard her sing many times at the Pro Cathedral. Her mother Amby was a great singer who instilled in Maura a love of old Irish music-hall ballads, light opera and the emotional dynamics of the great musicals. We met at TV’s flat on Abbey Street in Ennis, which was the third floor of a house owned by his parents, Derry and Tras Honan. Tras was a very strong-willed Fianna Fáil politician who had the distinction of being the first woman to chair the Irish Senate. She loved a good debate and I was always the willing young agitator full of youthful notions, itching for a political row. Some might say I haven’t changed much apart from the odd grey hair or two.

GARLICKED

I was completely taken in by Maura’s voice right from that very first rehearsal, unique with a rich, velvet timbre that weaves and meanders through each lyric line – so authentic, so full of emotion. We spent a lot of our evenings singing and listening to new music. Way down in the basement stood an old Aga, which fed and kept us warm during cold winter evenings. If you walk through the alley at Cruises Bar in Ennis today you will see remnants of that old cooking wonder, rusted and worn but still able to conjure a good memory or two. These days it seems to function as a drinks table and perhaps a quaint decorative reminder of a bygone era. If it could talk …

Cooking was a communal event in the flat, especially at the weekends when feasts were planned sometimes days in advance. One Saturday myself and TV were on duty to cook a spaghetti bolognese, which required, among other things, a clove of garlic. We were not familiar with garlic, and Ennis was not renowned for its stock of ‘exotic’ veg, but we managed to find garlic somewhere and returned very excited to prepare our new dish. What follows has been recounted several times by Maura O’Connell – in fact, I would go so far as to say she has made a career out of this story, filling up many minutes of air and stage time with it, particularly if I am anywhere within range. TV and I busied ourselves preparing the ingredients, carefully following the ragù recipe to the letter while Maura and our friend Paddy O’Brien sat upstairs listening to music. We sautéed the onions, followed by diced carrots, celery and then the clove of garlic. We added the beef, and as we poured in the wine, there was a sizzle and the room began to choke with the smell of garlic.

‘Jesus, it’s strong stuff, TV!’

‘Yea, it surely is. Sure, it might settle down with the wine.’

We kept going, but the smell was soon catching the backs of our throats.

‘Open up the window there, Jaysus,’ I said as we coughed and spluttered.

The aroma had made its way out into the hall, and up around the three flights of stairs to Paddy and Maura. There was a clatter of feet on the wooden stairwell and the kitchen door swung open.

‘Jesus, lads, the smell of garlic would kill you! How much did ye put in? It’s very strong.’

‘Only one clove,’ I replied. ‘The recipe said just one, but it’s very strong stuff.’

‘And where is the rest of it?’ she asked.

‘There is no more. We only got one clove, and that’s all we put in.’

Maura looked from one of us to the other. ‘Ye pair of eejits! Ye put the full bulb of garlic in, not a clove … oh, Holy Mother … I’m going to Johnny Griffin’s for chips.’

Years later, my poor mum made the same mistake after I suggested she try a little garlic in her stew. Her friends threatened to throw her from the bingo bus and leave her at the side of the road, miles from Ennis. My poor dad suffered with stomach ulcers, so he put down a tough few days for it too. He claimed the garlic was seeping through his pores. Needless to say, he was very wary of the clove after that. Poor Mum, only trying to spice up their life.

A CLAREMAN’S RAGÙ

I am not a fan of complicated menus. Why on earth would you want to cook pork fifteen ways in an apple and cider reduction, with a chargrilled peach salsa, served with honeyed baby carrots in a macadamia nut pesto, wasabi-soaked roasted cauliflower, kimchi-coated thrice-fried sweet potato chips with an essence of artichoke velouté, nasturtium leaves and a port jus? Honest to goodness.

Because I like to keep things simple, I love to cook Italian food; it’s the simplicity that’s the key, and the greatest challenge in cooking is to keep it simple – and seasonal. A few years ago, my brother-in-law married his Italian-Irish girlfriend, Rosa, in a beautiful castle at the foot of Castellabate on the Amalfi Coast. We spent the two weeks feasting on local food, including their famous mozzarella, produced at many local buffalo farms. In a small family-run restaurant up in the mountains we tasted the best ragù ever. It was delicious, rich and so full of flavour.

Rosa was born in Ireland, but her family maintains a very strong connection to her parents’ homeland. Over the years, she has been my go-to Italian foodie, particularly for clarity on Azzurri cooking, and she didn’t lick it off the ground, as her mum is never out of the kitchen. Naturally, each region of Italy boasts the best ragù, but they all seem agreed on one aspect – the pasta is hardly ever spaghetti, preferring instead wider, flatter pappardelle or tagliatelle, which is a better vehicle for the sauce. Ragù freezes really well, so if you have a little left over, save it for another day. It also works really well on a barbecued or roast potato, although I’m not sure Rosa would appreciate me suggesting the humble spud, she might just disown me for that idea alone. Some recipes use tomato paste but I find it far too intense a flavour.

A Clareman’s ragù

Serves 6 to 8

1kg good-quality beef mince with about 10 per cent fat content

2 tbsp rapeseed oil

1 medium onion, peeled and diced

1 celery stick, trimmed and finely diced

1 medium carrot, cleaned and diced

1 large clove of garlic, crushed

2 glasses of good red wine

400g tinned tomatoes, passata or homemade tomato sauce

200ml beef or chicken stock

1 dsp finely chopped fresh marjoram, sage, rosemary and a bay leaf

Sea salt and freshly ground black pepper

1 Break up the mince with your fingers and season with salt. Leave aside at room temperature.

2 In a wide-bottomed sauté pan, heat the oil and add the onion and celery. Slow-cook on a low heat for 3 minutes, then add the carrot and garlic. Cook for a further minute – do not burn.

3 Cover the veg entirely with a layer of mince, and leave it to cook for 6 minutes on a low heat. The underside should be browned but not burned, so a low heat is essential. Use a heat diffuser below your pan, if required. You may need to add a little extra oil.

4 Mix well and cook for 10 minutes, stirring constantly.

5 When the meat is cooked through, add the wine and reduce until it is almost dry. Be brave.

6 Add the tomatoes, stock and herbs. Cook at a low heat for 1 to 1½ hours, stirring often. Add a little water if it seems to be drying out.

JOE GALLIGAN’S FOLK CLUB

We had a very active and vibrant folk club outside Ennis in the little village of Crusheen, called the Highway Inn, owned and run by a wispy-bearded Cavan man called Joe Galligan, whose accent certainly softened from the few years in the Clare air. No PA system, no frills, just a small stage in a house full of listeners. Joe usually sat at the back of the room guarding the silence vigilantly, ready to pounce at the mere hint of a whisper.

He had the foresight to help set up a national grid of folk clubs, which allowed artists to pull together a series of gigs around the country. Folk clubs on the circuit usually met in January to discuss regular touring artists, listen to recommendations or requests from new acts, and set out a tour plan for the year ahead. Clubs from Clonmel, Limerick, Carrick-on-Shannon, Carrick-on-Suir, Roscrea, Dublin, Waterford, Kerry and several others were linked into a rolling schedule from Tuesday to Saturday, which meant relatively little travel time between shows. In that little room in Crusheen we heard a very young Barry Moore (aka Luka Bloom), Henry McCullough, Hobo Junction, Dolores Keane and so many more wonderful Irish and international artists. Such was the high standard set by the grid that emerging or new talents were always assured of a reasonably full house of dedicated club members who loved their music and embraced the opportunity to hear new tunes.

Joe gave myself and Maura our first gig, and we were so excited – but we had no name, and for some reason back then you had to have a band name. While flipping through our album collection, we came across a Dan Hicks and His Hot Licks song called ‘The Tumbling Tumbleweeds’. ‘Tumbleweed’ it was to be. I still remember that first gig, as both of us, extremely nervous, stumbled through our first song, but the audience cheered us loud and long – not a tumbleweed in sight. Such a great feeling. Joe invited us back many times, all the while encouraging us to spread our wings and get out on to the club circuit. We spent weeks writing and learning new material, and soon were playing at the National Institute for Higher Education in Limerick with a very young Stockton’s Wing, who were beginning to cause quite a musical stir around Ireland.

PJ CURTIS

As a young boy in Kilshanny on the edge of the Burren, PJ Curtis went twiddling the knobs of the wireless radio and found AFN, the Armed Forces Network radio station broadcasting from Stuttgart. There he heard the sounds of the Grand Ole Opry, rock and roll and the Mississippi blues. His family was steeped in traditional music; his mother played fiddle and was part of the great Lynch family, who were, and still are, at the core of the Kilfenora Céilí Band. But when the likes of Muddy Waters and Sonny Boy Williamson came seeping through the walls of the Old Forge cottage, PJ’s world changed forever. His mother eventually found a guitar for him in Limerick, and PJ was on his way.

At sixteen he found his way to Belfast, joined the RAF and was stationed outside Bath. In 1962 he was playing with beat group Rod Starr and the Stereos, gigging regularly around the area. The Beatles were coming to Bath and the Stereos were booked to play support. A few days before the gig, their slot was given to another band, and to compensate the promoter put them on with Jerry Lee Lewis. PJ was delighted, as he was a fan of the great man. He got to see the Beatles play and be on the same stage the following week with Jerry Lee.

He was sent to Borneo to work as a radio technician. On his return to Ireland he met with a young Bothy Band, who were creating innovative Irish music, with guitarist Mícheál Ó Domhnaill, Paddy Keenan on pipes, Tríona Ní Dhomhnaill on clavinet, Matt Molloy on flute, Donal Lunny and Tommy Peoples on fiddle. Tommy was soon replaced by Kevin Burke. PJ worked as a driver and roadie for the Bothy Band while producing albums for Mulligan Records in Dublin.

When we met PJ Curtis, he had recently finished touring with the Bothy Band and was back living at his Old Forge cottage while producing the first of his many iconic Irish folk music albums in Dublin studios. PJ introduced us to a whole new world of music and emotions through blues, gospel, rock, trad and American country. We discovered Mahalia Jackson, Richard Thomson, the Mills Brothers, Mississippi John Hurt, John Coltrane, Robert Johnson and Lightnin’ Slim. None of these artists were available at local record shops, so I bought most of my music from a Welsh mail order store called Cob Records, and my order sheet grew with each visit to PJ’s cottage. Cob stocked thousands of albums and sent out weekly catalogues of old and new releases, all sold at discount prices. It was my brother Ger, an avid collector, who had originally discovered Cob, and when the latest brown package with the green par avion sticker arrived, we’d tear it open to give it its first spin on our turntable as fast as we could. Many years later, while on tour in Wales with Ronnie Drew, I went in search of Cob Records. I found it in Porthmadog, where I met an old man who remembered sending lots of records to a house in the west of Ireland. He said he loved to see our catalogues arrive back with some of the oddest of requests. I think Ger and myself kept his international business going for a few years.

PJ would go on to record some of the great Irish albums of that era with Scullion, Freddie White, Maura O’Connell, Sean Keane, Mary Black, Altan, Dolores Keane, Mick Hanley, and of course two great albums with Stockton’s Wing, including our two big hits. These days PJ splits his life between Clare and Spain. He has been part of my music life since the early days, and I owe him thanks and respect for his constant support down all of these years. He saw something in myself and Maura O’Connell way back in the day, and gave us both great encouragement to get out there and fly. When he heard my songs for Stockton’s Wing he built a wonderful platform so that the world could listen.

Maura’s salmon chanted evening

Serves 4

Maura O’Connell is an exceptional cook, dedicated to good produce and great recipes – and she always hosts a mighty fine shindig. She spent most of her youth handling and selling fish at her family shop, so you are always guaranteed a tasty fishy dish.

2 large fillets of salmon, with skin (about 300g each)

120g baby spinach leaves

150g crumbled feta cheese

Oil, to grease

1 tsp lemon zest

4 large tomatoes, finely chopped

4 cloves of garlic (not a bulb!), crushed

Boiled rice and salad, to serve

1 Preheat the oven to 170°C/150°C fan/gas 3.

2 Wash and dry the salmon on kitchen paper.

3 Blanch the spinach by plunging it into boiling water and removing immediately. Place it in a colander to drain. Coarsely chop the drained spinach, and mix with the feta cheese and lemon zest.

4 Place one salmon fillet skin side down on an oiled baking tray or oven-safe dish. Spread over all the spinach mixture. Place the second salmon fillet on top, skin side up.

5 Mix the tomatoes and garlic together and spread over the salmon, completely covering the top and sides.

6 Bake in the oven for 40 to 45 minutes.

7 Serve with boiled rice and salad.

ON TOUR WITH BETSY

TV owned a beautiful 1965 black Morris Minor with wing indicators that flicked out like a pair of hands when engaged. Maura christened the car Betsy prior to our first tour around the folk clubs of Ireland. After months of writing, learning new songs, rehearsals, planning, playing support gigs and sessions, we were now out there on our own, with our names on our posters, playing our music on our very own stage. It was a very exciting time. We played in Carrick-on-Shannon with a very young Charlie McGettigan, and we also played at the famous Clonmel Folk Club, still going to this day with Ken Horne at the helm.

BOBBY CLANCY

Bobby Clancy and his wife Moira ran a folk club in the basement bar at their hotel in Carrick-on-Suir in Tipperary. Bobby and Moira loved our music and sat with us for hours after the show Maura and I played, passing on some hard-earned experience from Bobby’s days with the Clancy Brothers. ‘Guys, it’s not just a performance, y’know; it’s a show as well. You can both sing and play well enough, but you need to tidy up between the numbers. There’s far too little going on, and you need to keep the audience’s attention. Talk to them, and have a little fun. In the early years of the Clancys we learned to keep the show going by adding little snippets of poetry, or a few funny stories.’

‘And you, my dear Maura. You need to stop looking at your feet. Look up, and smile at them.’ Such a lovely man.

THE NATURAL DISASTER BAND

On St Stephen’s Day 1978, Tumbleweed played a one-off charity gig at the Green Door Youth Centre with a full band aptly named the Natural Disaster Band, for very obvious reasons. The gig was a nightmare to set up, with so many obstacles put in our way, PA problems with cable issues, not enough microphones or stands, amps breaking down, all sorts of buzzing sounds, electricity failure and no time at all for rehearsals, but we got through it – and I think most of the musicians in Ennis participated in some way or other to make that a very special day. On the back of it, PJ Curtis encouraged us to start putting songs down on tape so that he might spread it about the Dublin music scene, where he worked as a producer with a couple of record labels. A month later, TV set up a recording studio in his parents’ house and we made our first demo cassette recording. I found the old cassette sleeve only recently, which was drawn in multicoloured crayon by my then girlfriend Bebke Smits of Doolin Hilton fame. Bebbie designed individual sleeves for many of our friends, and this was called ‘The Sea of My Imagination’. Nothing much came from that particular demo, but we did enjoy a few great gigs around the country and one in particular at Smokey Joe’s Café in Galway.

SMOKEY JOE’S CAFÉ

In the late 70s the Students’ Union set up Smokey Joe’s Café as an alternative lunchtime eatery for the Students’ Union in a prefab building behind Ma Craven’s coffee shop, close to the popular Aula Maxima at University College Galway. It was run by student activist Ollie Jennings, an energetic, selfless promoter of the arts who later created the Galway Arts Festival, put De Dannan firmly on the popular map and introduced us to the wonderful music of the Saw Doctors.