Полная версия

Beautiful Affair

In that same year as they took up the pub, my secondary schooling came to an end at Rice College on the banks of the river Fergus, not far away in Ennis. I was a reluctant student to say the least; I had no interest in school apart from history and economics, the latter receiving most of my academic attention. The enigmatic Jody Burns, with his appearance and antics of a nutty professor, was a gifted teacher who managed to corner my full attention on matters of supply and demand. I duly received an A in my Leaving Certificate examination in economics, which was a great shock to many – but not to Jody Burns. He was very proud of my achievement but expressed great disappointment on hearing that I would not be going on to study economics in college. These days third-level education is a natural progression for so many students, but back in the 70s the order of the day for the majority of us school-leavers was to secure a ‘grand pensionable job’, settle down, buy a house and raise a family.

Little did I know while sitting those last exams that as soon as the school books hit the waters of the river Fergus, I’d be in a car on my way up to Doolin to play music with my brother Kieran and first cousin Paul Roche, right here in this very room where I sit today in McGann’s. During that first summer of freedom I shook off the shackles of a sheltered Catholic upbringing. I made many new friends, discovered love, expression and songwriting. I recognised early on that the fish and lamprey eels of the Fergus would benefit much more from my books than I ever did, while I concentrated my further education on the life and music of North Clare and beyond.

MY FIRST KITCHEN JOB

Up to the mid-40s transatlantic flights – mainly seaplanes – had to stop to refuel at Foynes in West Limerick on their way to continental Europe. During the Second World War Foynes became the busiest airport in the world. Shannon Airport was then established in 1945 as Ireland’s first international airport, and within a few years it became the world’s first duty-free airport, operating as a gateway between North America and Europe, as most aircraft still required refuelling for long-haul flights.

In that summer of ’76 I got a job as a kitchen porter in the airport’s ‘free-flow’ restaurant, doing my best to get to Doolin for our Tuesday and Thursday night sessions and up again on Friday evening for a weekend of music and craic. The job was supposed to be a stepping stone either to a culinary career or to a more secure position in the airport or surrounding industrial hub. The busy kitchen served passengers, flights, all airport staff and stocked all duty-free restaurants. Most of my day was spent either on wash-up or working the conveyor belt, which delivered mounds of dirty dishes and cutlery to the sinks. Life as a kitchen porter was non-stop grief, thanks in particular to an ogre of a chef who barked and bellowed orders through an early-morning fug of stale alcohol. Stockpots and skillet missiles whizzed past my right ear to rattle against the sides of the stainless-steel basin before sinking into an angry, greasy ocean of bobbing and weaving pots and pans. The two of us manning the station were not allowed to speak a word, but we soon developed early warning signals for any incoming, including the main man himself, who would storm over with a badly washed pot, reload and fire it back at us again with bonus expletives. By the end of lunch, his anger grew as his hangover craved its afternoon cure. His venomous eyes have stayed with me, but it was a lesson to me to learn my surroundings inside out.

My next-door neighbour and childhood friend Ken Shaughnessy also worked in that kitchen as a commis chef. He went on to culinary college and became an executive head chef for an international hotel chain in Germany. On the very rare occasions we meet, we toast many schnapps to our wonderful childhood, that kitchen and good old Cerberus. Perhaps he was the making of us after all, as our love of food survived and neither of us have ever tolerated kitchen bullies, no matter how important they consider themselves. I will never understand how aggressive chefs get away with humiliating people in their place of work.

I moved quickly from the kitchen to the duty-free mail-order department, packing and posting Waterford crystal, Belleek china, shillelaghs and leprechauns to exotic-sounding destinations like Pine Ridge, Vermont, Wyoming, Montana and Biloxi. I finally left Shannon to work with my friend TV Honan at a newly opened drop-in centre for teenagers in the old refurbished National School in Ennis. It was the first of its kind in Ireland, the brainchild of Sean Sexton, a very proactive, clued-in priest. We called it the Green Door after a short story by American writer O. Henry, a tale of romance, adventure and fate as we search for a door to opportunity. I often think that the story somehow reflected my decision to break free from that grand pensionable position to search for my own green door. With an unyielding determination to find a way to the music I convinced Mum and Dad by telling them my wages at the Green Door were higher than at Shannon, when in fact they were a lot lower, but I figured I could make up the loss from sessions and gigs.

ROOM WITH SEA VIEW

On my weekend visits to Doolin I slept behind the pub in a caravan and in tents beside the beautiful Aille River, or found a sleeping space in the upstairs restaurant. Come the morning there was the usual scurry to clear the beds and clean up last night’s fun to get ready for early lunch. One summer a group of German tourists found their way into a disused, dilapidated, roofless house at the entrance to Doolin pier, cleared it out, filled it with straw and hay and pinned a sign at the front entrance:

Doolin Hilton Hotel

All welcome

Please keep tidy

After closing time, we had some memorable nights at that waterfront Hilton. Everyone checked in, signed the guest book, played music, sang songs and listened to stories from all around the world. We heard about Aboriginal dream time, the Northern Lights, American Indians, Nordic folk tales and magical Dutch fairy stories, while smoking reefers and drinking beers on beds of straw beneath a blanket of sparkling stars. All strangers who entered left as friends. I fell in love there with Bebke Smits, a free-spirited young woman from Boxtel in the Brabant district of southern Holland. Bebke sang Dutch folk songs, wrote and recited deep and weird poetry, danced very freely and was extremely comfortable in her hippie skin. She introduced me to vegetarian food, and gave me my first Herman Hesse novel, Narcissus and Goldmund, a book I return to time and again. It’s a poignant tale about young Goldmund, who develops a friendship with a slightly older and more committed monk, Narcissus, at a monastery somewhere in Germany. Goldmund strays into the woods one night, where he meets a beautiful young woman who seduces him. The confused novice seeks counsel from the older Narcissus, who encourages him to leave the monastery and embrace life beyond the walls rather than remain in search of salvation. On the journey that follows, Goldmund becomes a talented carver but refuses to join the carving guild, preferring to continue unbound on his road to understanding. He meets and loves many other women along the way, and survives the Black Death and all its ugliness. Eventually he returns to his friend Narcissus, where in the monastery the artist and philosopher speak freely about their lives in a beautifully written story.

Myself and Bebke ultimately drifted apart and she went home, got married and seemed quite content until suddenly, out of the blue, she contacted me around 1981. She was in Dublin, distressed following a very acrimonious break-up. We met at the People’s Park in Dún Laoghaire and found our way to Walter’s pub on the corner. As we entered, the barman called me aside to say it was men only in that section and he could not serve my girlfriend. We were stunned. Beb stood up and let him have it, refusing point-blank to leave without having a drink. He eventually poured her a glass of stout and we sat in a pub full of astonished old men either in awe or aghast at this feisty young lady dressed in purple, with beaded auburn hair, bedecked with all sorts of bangles and rings, speaking with a very strange accent.

It would be years before we met again, when she wrote to say she was taking her new partner on a trip to Clare to show him her place of youth and magic. We sat together for hours remembering the days of music and love, Narcissus and Goldmund again.

Her purple dress in slight decay,

Winter weaving its weary tale.

Outside swallows fly,

Moving out on a twilight sky.

– ‘Black Hill’, The Crooked Rose (1994)

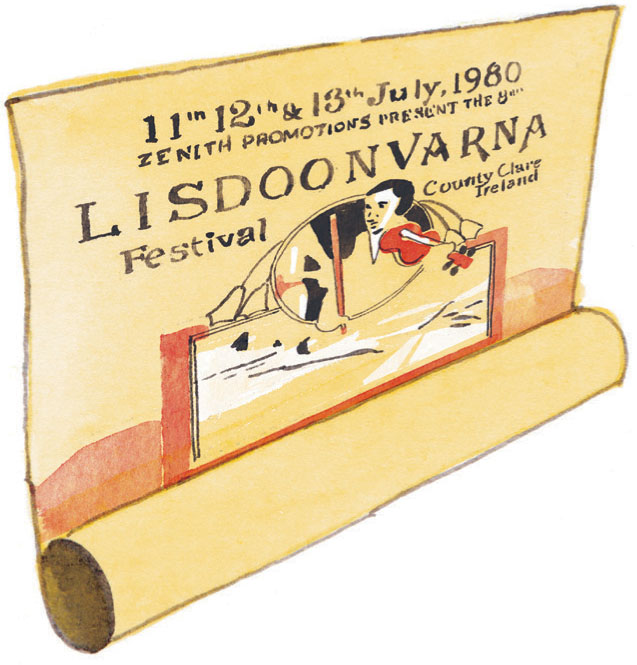

MICHO RUSSELL, STAR OF THE LISDOONVARNA FOLK FESTIVAL

One of Tommy’s crazier notions was an open-air festival, in his mind’s eye featuring us alongside Van Morrison. Though that never came to pass, he had been on to something; the Lisdoonvarna Folk Festival did happen two years later, and Tommy was right in the thick of it all, running the bar and dishing up his simple but legendary beef stew. He made so much stew that first year that every neighbourhood freezer was commandeered for storage, and it was so popular that it stayed on the specials board for most of that winter.

Over the fireplace in the pub hangs a motif that says, ‘Everyone who visits this place brings happiness; Some by coming in … some by going out.’ How true those words ring now as I scan the walls. Among the photographs I spot the famous Russell brothers, Micho, Pakie and Gussy. They came from a family of musicians and storytellers and played for many house dances, céilís, and were regulars at O’Connor’s pub on Fisher Street. In the early 70s Micho singlehandedly put Doolin on the music map with his deceptively simple style, engaging humour and legendary charm. Micho loved the road, the theatres, audiences and the adulation – especially that of the young European ladies, who were enchanted by his eccentricities. Their arrival in Doolin to visit him was well reported locally, often leading to much whispered speculation about the ‘goings on’ at the cottage by the sea.

For me, his crowning musical moment had to be an appearance on a beautiful sun-drenched Saturday afternoon at the Lisdoonvarna Folk Festival. Micho sat centre stage, nonchalantly playing away on the whistle, when suddenly, mid-tune, a beautiful young Swiss woman dressed in translucent pink chiffon sashayed onto the stage in a freestyle ballet, gliding around a seemingly oblivious Micho. She drifted effortlessly across the entire stage, looping back to Micho, now beaming and winking in her direction. A sleepy afternoon crowd quickly awoke to the emerging scene, and the noise grew as people clapped along and cat-called. When the dance finished, Micho stood hand in hand with the dancer, who gave a graceful ballerina curtsey, and they walked off the stage, leaving a festival in consternation. It was all people could talk about for weeks, with reviewers relegating headline acts into the ‘also ran’ bracket as they honed in on the spectacle of Micho Russell and the girl in the pink nightdress. It was the only show in town.

TOMMY IN AMERICA

In early 1978 Tommy McGann, having spent a day in his pub drinking with a group of Americans, decided to join them on their return journey to Connecticut. He had neither luggage nor a passport. On his arrival in the US, he talked his way through customs. Back then, American customs and the world in general were a little less suspicious of the traveller. Tommy phoned his mother to announce that he was now living in America for a while and to please tell Tony to mind the pub while he was away. He would be home soon. Though it was a spur-of-the-moment move on his part, it proved to be the beginning of an adventure that lasted many years, a move that positively affected the lives of the thousands of people who connected with him directly or indirectly either in Doolin or on the shores of America.

He moved to Boston to work at the Purple Shamrock, a downtown Irish bar that was the first port of call for many Irish immigrants. He then opened his own bar in Cape Cod called the Irish Embassy, which quickly became a consular office of sorts for countless Irish visitors. He renamed it McGann’s, then opened a second Irish Embassy in Easton, Massachusetts, and relocated back in downtown Boston on Friend Street, a short walk from the famous Boston Garden, home to the Bruins and the Celts. He settled in there for the rest of his short life.

A second McGann’s pub was opened next door, which included two youth hostels. The hostels were an inspired addition and welcomed by many Irish immigrants, including my own brother-in-law Stan, who to this day regards Tommy as his saviour. Having arrived in America, almost penniless and jobless, Stan worked as the doorman and in true McGann fashion was available for any other duties that might arise. Tommy worked a very simple system for immigrants: new arrivals were taken in by Irish people and looked after; months later, you returned the favour to the next wave. It was an unwritten rule that was never questioned or considered, and everyone who came through was guaranteed a solid, friendly and dignified beginning to their new world far away from home.

Tommy was very particular about his menus in the pub. He used many local ingredients, but also imported Irish goods like sausages, beef, bacon, Tayto crisps and, at one stage, brown bread. I still recall our first visit to the Purple Shamrock all those years ago. When we arrived, Tommy had us leave all our bags down in the basement and then treated us to a feed of eggs, sausages and baked beans – Boston baked beans.

Quick Boston baked beans

Serves about 8

Oil or butter, for frying

600g thick streaky bacon, chopped

1 small onion, peeled and diced

1 tsp mustard seeds

1 × 400g tin of cannellini beans

1 × 400g tin of kidney or pinto beans

200ml homemade tomato sauce or passata

3 tbsp molasses

1 tbsp maple or golden syrup

A pinch of dried oregano

Sea salt and freshly ground black pepper

1 Preheat the oven to 150°C/130°C fan/gas 2.

2 Heat the oil or butter in a frying pan. Add the bacon and onion and fry until golden, then add the mustard seeds.

3 When the seeds begin to pop, stir in the beans, tomato sauce or passata, molasses, syrup and oregano. Taste for seasoning.

4 Place in an ovenproof dish, and bake in the oven for 40 minutes.

Note: The traditional method is a very slow cook using fresh beans or part-boiled beans. Traditional recipes also use either molasses or syrup, but I added both to keep everyone happy.

Tommy’s pubs on the Cape and in Boston also played host to countless touring Irish musicians, who regarded them as recharge stations during long, arduous tours. He was well established as a businessman there, and, crucially for someone dealing with a lot of young messers far from home, he was also well connected to the authorities. I remember one occasion when a member of our band decided to go for a midnight swim at a Quincy motel, only to be arrested for trespassing and taken away in his soaking underpants to spend the night freezing in a local cell. The following morning, he was arraigned in the same attire, but Tommy’s successful plea for clemency meant we could carry on with our tour, as long as our swimmer remained on dry land and donated a few dollars to a local church fund.

SAD FAREWELL

Clearly, Tommy’s greatest legacy is his generosity to friends and strangers; there was no dividing line between the two for him.

He died tragically in a car accident in County Clare in 1998 when he was only forty-five, having already survived cancer. The city of Boston and the people of Clare alike wept in each other’s arms at his passing. For one St Patrick’s Day, the city named a street in his honour. I, like thousands more, owe much to his friendship, spirit and character. The years pass swiftly now, but every time I return to Doolin memories are still strong, and Tommy is always present in my thoughts, audacious as ever, smiling, jibing and dreaming up his next crazy adventure.

TOMMY PEOPLES AND CHRISTY BARRY’S FLUTE

One particular set of photographs on the wall in McGann’s really caught my eye. There’s cockney Tom Thomson, driving his old red bus with an engine that constantly howled in pain, almost longing to be decommissioned. Next to Tom, fiddle supremo Tommy Peoples, who worked with my dad at the County Council and toured with the ground-breaking Bothy Band. Tommy’s playing was on another level, from a different place, sometimes dark, sometimes melancholic, but always exciting and performed with such panache. He was an introverted character and, in those days, insisted on taking me along to play guitar at all his gigs. I was only a novice with very few chords, but he said he loved my rhythm and the way I accompanied tunes. That meant more than I could ever express in words, and unfortunately he’ll never know the effect he had on my confidence as a young musician.

Next to Tommy is Christy Barry, who played concert flute and whistle from morning to the late hours, regaling tourists with countless tales. When a crowd had gathered, Christy dipped the flute in his pint, proclaiming to the young ladies gathered round that the Guinness was very good for his flute. Christy had a glint in his eyes that could woo a stone. I hear he still plays wonderful music at house concerts around the county. I also hear the Guinness has been replaced by large pots of tea.

THE THREE AMIGOS

I scan along the wall and stop at three delightful characters. I immediately break into laughter. It’s the formidable Donegal/Dublin trio of Skippy, the Sheriff and Rory O’Connor. They arrived in Doolin in the late 70s and held court daily at McGann’s, entertaining the masses with their wit and beguiling charm, snaring many tourists for free drinks and food. They easily passed a day’s drinking without spending a penny. Tony ‘Skippy’ Reid had that acerbic Dublin sense of humour delivered with impeccable timing, sparing no one in the process. One day a customer enquired about McGann’s ‘world-famous Irish stew’. The barman talked up the stew, explaining its popularity among locals and tourists alike. ‘Some say it’s the best stew in the world,’ he boasted. At the time Tony McGann ran the kitchen and he was very proud of his stew, and with Tony well within earshot, Skippy stood up from the stool, turned to the customer and said, ‘Stew me arse … they should have called it Aran Islands stew, ’cause it’s just three small pieces of meat surrounded by fuckin’ water.’ He may have been barred on that occasion but his expulsions were never long served. On another occasion Skippy hurt his knee and was walking around on crutches. The locals organised a benefit dance to cover medical expenses under the banner ‘The Needy Knee’ at the Hydro Hotel in Lisdoonvarna. As the evening wore on, the music got the better of him and he rose to his feet and started dancing. The Sheriff grabbed him and sat him back down: ‘Will you sit down, you eejit, we’ll get lynched!’

He is literally part of the furniture at the Hydro, where a bar stool engraved ‘Skippy’s Seat’ stands proud in his preferred position at the end of the bar with a full view of all proceedings.

Whenever I stayed at McGann’s, I mainly played music and when required, I served beer, made the sandwiches, soups, stews, swept the floor, collected glasses or carried out whatever task was presented. There was no question of any kind of demarcation, which was in total contrast to my job at Shannon Airport. Everyone just got on with it. On occasion when customers wished to speak directly to the chef, Tommy chose whichever one of us looked the most respectable, and urged us to say by way of an opener that we were trained as chefs at the Ritz in London and gave it all up to live the life here in Doolin.

McGann’s world-famous Irish stew

Serves about 4 to 6

I often cooked their stew, and in later years included it on several of my menus. I like a simple stew, but good meat, veg stock and herbs are essential. I use lamb neck or shoulder pieces, but I have used gigot chops. I like to use lamb stock if I have some stored in the freezer, though chicken stock is fine too. Fresh thyme is essential.

Olive oil

1 large onion, peeled and finely chopped

1kg neck of lamb, chopped into bite-size chunks, lightly salted and set aside

2 large carrots, peeled and chopped

2 celery sticks, peeled and chopped

1 parsnip, peeled and chopped

500ml well-seasoned stock (see below)

1 dsp fresh thyme leaves

I tsp chopped fresh rosemary

1 bay leaf

2 large potatoes, peeled and chopped into bite-size chunks

Sea salt and freshly ground black pepper

Extra fresh herbs, finely chopped, for garnish

1 In a medium-sized pot, heat a little oil and fry the onion gently for about 3 minutes.

2 Add the lamb pieces and let them get a slight colour, about 6 minutes.

3 Add the carrots, celery and parsnip and mix.

4 Add the stock and herbs and bring to the boil, then lower the heat and simmer for 40 minutes.

5 Add the potatoes and cook for a further 25 minutes. Taste for seasoning. Serve garnished with the chopped herbs.

Lamb stock is easy to make yourself. Get a few lamb bones with a little meat on them into a large pot with 2 litres of water, a carrot, some celery, thyme, a bay leaf, an onion and a few black peppercorns. Boil for about 2 hours, stirring every so often, then strain and return to the heat until reduced to about half. When cold, remove the layer of solid fat. You can freeze what you don’t need, ready for other recipes later.

McGANN’S EQUALLY WORLD-FAMOUS TOASTIE

Under the mantelpiece by the old kitchen I spot a photo of a very young Davy Spillane with his long, flowing curly hair, taken just before he conquered the folk world with his incredible piping and innovative, modern and progressive approach to writing and arranging music for the uilleann pipes. We played many sessions together back in the day, and we both practically lived on the house toasted sandwich special of ham, cheese, onion and tomato. The hams, or occasional corned beef, were boiled in large pots in the kitchen, we sliced the red Cheddar from a massive block, the onions and tomatoes were either sliced or very roughly chopped according to the skill set of the appointed ‘chef’ on duty. The ham caused us the most trouble, as we tended to eat more than we filled, and on top of that our slices were always very thick. ‘Ah, for fuck’s sake, lads!’ Tony would moan, followed by a lecture on the values of portion control. But the trick to the toasted special was the magic toastie bags: two slices of liberally buttered bread filled with fresh ham, onions, cheese and tomatoes, wrapped in a special heatproof plastic bag and toasted on a double-sided grill. The bag blackened in the intense heat, causing the cheese to caramelise at the edges. You had to allow a minute for cooling, to avoid second-degree lip burns, before cutting through to a waft of warmed ham, tomato and onion soaked in the burnt liquid Cheddar. A sensorial symphony filled your nostrils, a symphony like no other from our fine-dining days at McGann’s.

The toaster is still in operation today, and I was brought into the kitchen to say hello. The chef says it has acquired a mind of its own in old age and only works when it feels like it. I think it has earned that right.