Полная версия

Beautiful Affair

COPYRIGHT

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

FIRST EDITION

© Mike Hanrahan 2019

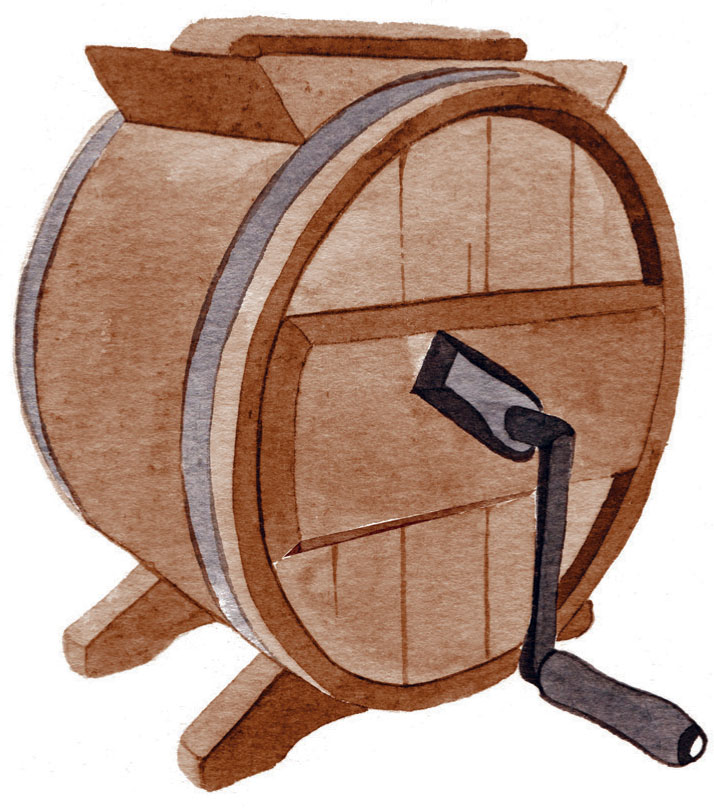

Illustration © Charlotte O’Reilly Smith 2019

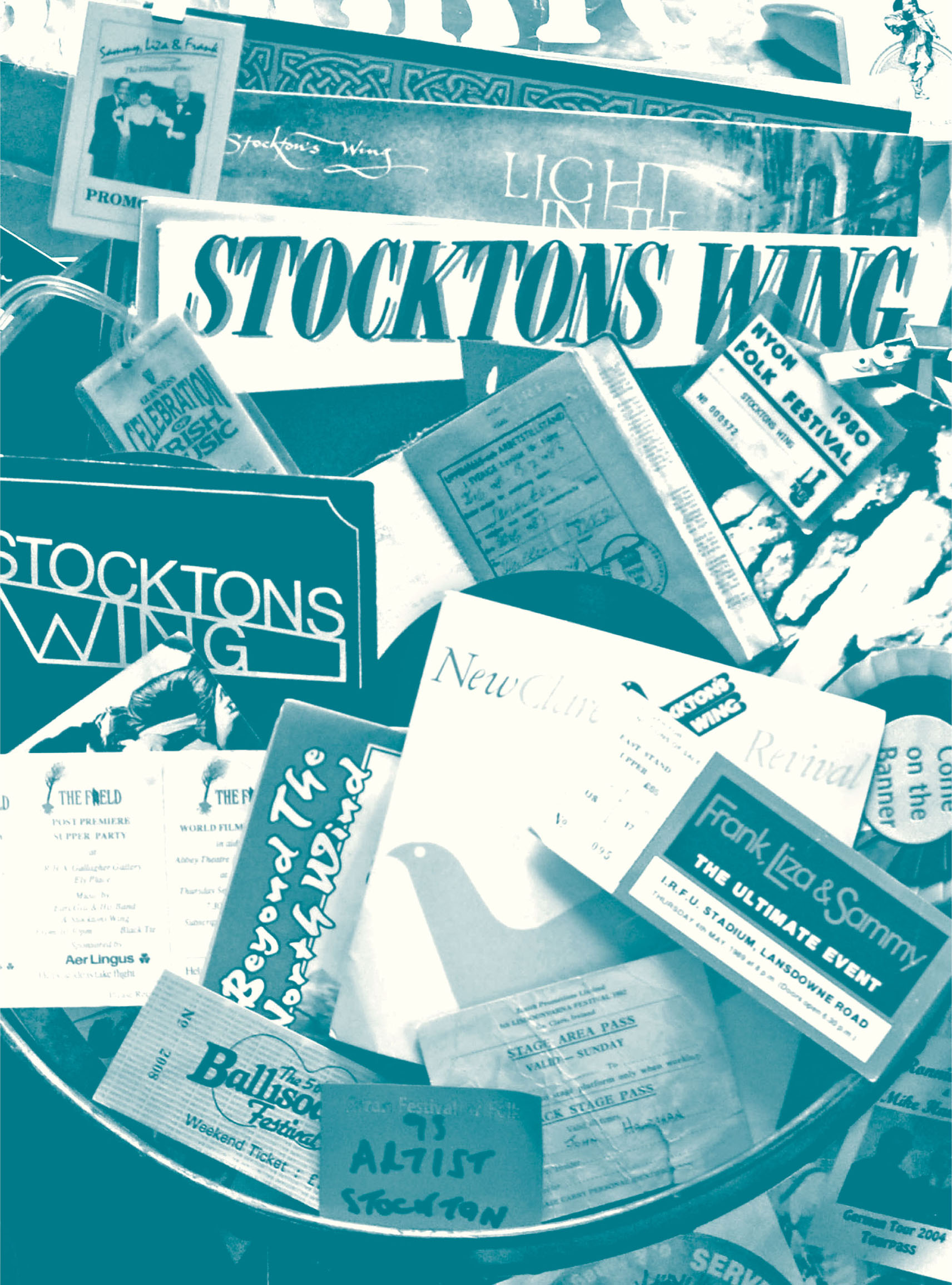

Photographs from the author’s personal collection unless otherwise indicated

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

Cover illustrations © Charlotte O’Reilly Smith

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Mike Hanrahan asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at www.harpercollins.co.uk/green

Source ISBN: 9780008333003

Ebook Edition © October 2019 ISBN: 9780008308759

Version 2019-09-10

DEDICATION

To Donna

CONTENTS

COVER

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT

DEDICATION

CHAPTER 1 FIREFIGHTER

CHAPTER 2 DOOLIN

CHAPTER 3 MAURA O’CONNELL

CHAPTER 4 TAKE A CHANCE ON ME

CHAPTER 5 BAND OF BROTHERS

CHAPTER 6 FINBAR FUREY

CHAPTER 7 RONNIE, I HARDLY KNEW YA …

CHAPTER 8 LEGENDS

CHAPTER 9 VAGABONDS

CHAPTER 10 BALLYMALOE COOKERY SCHOOL

CHAPTER 11 LEARNING CURVE

CHAPTER 12 PAT SHORTT’S BAR

CHAPTER 13 ELEANOR SHANLEY

CHAPTER 14 ARTISAN PARLOUR & GROCER

CHAPTER 15 ENCORE

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

CHAPTER 1

FIREFIGHTER

Farmer John, plough your fields, bring the seed to grain,

Feed the hungry, fill the belly of the traveller as he sails,

A weary heart, a tired soul will try come what may,

Farmer John, plough those fields, help him on his way.

– ‘Firefighter’, What You Know (2002)

THE CROSSING

My parents grew up in the neighbouring farming communities of Barntick and Ballyea in County Clare. As a young couple they chose to start their new life in the burgeoning outskirts of Ennis, which offered opportunities for work and a new rented home in which to raise their young family. In 1957 they moved to the just-built St Michael’s Villas on the edge of Ennis, and there they raised eight children, six boys and two girls: Gerard, Joseph, Kieran, myself, Gabriella, Adrian, John and Jean. I was in the middle; the youngest two were twins. Dad provided and Mother nurtured.

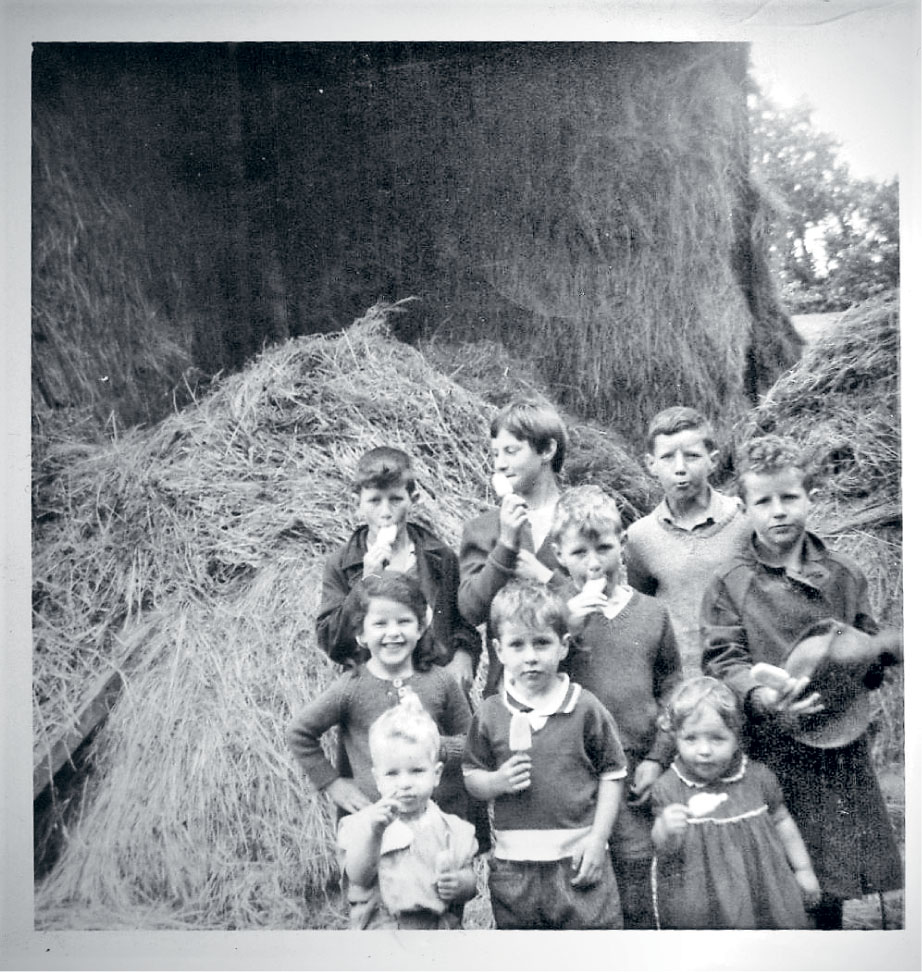

When we were young, our summers were spent secluded on my grandparents’ farm, a few miles from civilisation. We walked to and from the village of Ballylea every Sunday morning, dressed in our finest to attend Mass at the parish church. The farm was our domain, where our friends were the animals and our sustenance came from the very land we roamed.

Come September, we returned to the bustling terraces of Ennis, playing games on the green with the O’Loughlins, the Howards, the Hahessys, the McMahons and the Dinans. By contrast with the farm, it was a noisy playground where you fought to shout your name.

Even as children, our ‘country’ mentality jostled for position on the streets and in our schools, while the country folk saw us only as townies. We were somewhere in the middle, criss-crossing – in language, expression, attitude and mind.

But home life had surety, unity and a purpose, constantly nourished with wonderful music and beautiful food. Music and food have kept me on track at every crossing.

DAN JOE

My grandfather, Daniel Joseph Kelleher, was born in 1898 at No. 2 Victoria Villas, Victoria Cross in Cork City, and was sent to live with his aunt Mary, who lived with her husband Patrick Nagle in Ballyea in County Clare. It was not unusual in those days for large families to send some of their children to live with their aunts or uncles to help alleviate the pressure on food and board at home. Dan Joe grew up in Ballyea and married a local girl, Margaret McTigue. They settled down to raise their family of four boys and one girl, my beautiful mother, Mary Kelleher.

Dan Joe was a gentle man who worked for the local government and spent the rest of his time working the farm with Margaret, raising cattle, pigs, sheep, geese and hens. He wore a dark grey fedora that only left his head when he sat down to eat or attend Sunday Mass. We spent our entire summer school holidays on their farm, a playground of vast open acres of grazing fields, stables, hen houses, tackle room, straw-bedded sheds and a monstrous metal-framed hay barn that would fill to capacity during our stay. At the rear of the milking parlour was a slurry pit which fed the land and gave off the most noxious of smells in the July heat. Manual farm machinery speckled the yard, along with milk churns, water barrels, a couple of dogs and the ever-present Charlie, the wonder horse, our absolute best friend in the whole wide world.

Beyond his work on the farm, Dan Joe loved hurling and Irish music. He stood proud at the back of the Ballyea or the Clarecastle village halls whenever we performed at the variety concerts and always cheered our successes. He loved the sound of the accordion so much he gifted one to my brother Joe, who played it for a few years.

He was quite ill towards the end, and in his final days, a hush surrounded the visit of a local healer, who was called to administer the sap from the bark of a birch tree which was boiled in milk along with a few other secret ingredients. In rural parts of Ireland, doctors were expensive, so most people looked to the local healers and their folk medicine for help. The practitioners were dedicated, and believed in the virtue of their treatments, with very little money exchanging hands, if any at all. Some local communities continue to believe in the power of these natural remedies.

Alas, it was all too late for poor Dan Joe. I was almost twelve, and his was my first funeral, an event that left an indelible mark on my memory.

THE WAKE

I still see that never-ending procession of black suits and shawls as they shuffled their way through the front door into the crowded parlour, passing the mirrored oak sideboard with its fresh flowers and photographs of happier days. Onwards they moved, in around to a smoke-filled kitchen with its glowing fire, down under the narrow staircase to a darkened room that smelled of church candles and lilies and echoed a constant hum of prayer and sorrow. Circling the bed, they blessed themselves as they passed by a very peaceful-looking Dan Joe, dressed in a crisp white shirt and a grey paisley tie. He lay motionless and cold, but free of all the pain that had etched his face in the recent days. Ushered on by my uncle Tom, the latest batch of mourners offered their condolences before rejoining the mêlée, talking, laughing, crying, whispering, drinking and eating from plates of sandwiches and cakes brought in by neighbours and distributed eagerly by all the grandchildren.

Later, as the crowd dwindled, I sat nervously staring at his figure, wondering how it was possible that I would never hear his voice again, never see that smile or feel the warmth of his arms around my shoulders, and my thoughts drifted to poor Charlie and I wondered how he would cope now that his master was silent. He would surely miss him in the morning and every other morning after that, the click of his voice, the gentle tug of the reins and all their little chats during the daily rituals of tacking and farming.

‘How is all this possible?’ I thought. Maybe in the morning he might come back to take us all down to the L-field to gather the cows. But the following morning was spent in a crowded church of whispered prayer followed by the short procession to an adjacent graveside where men lowered his coffin deep into the ground. A raw, sudden swell of tears and sadness filled the autumn air as the pebbles hit the wood to finally signal his end.

On an old country lane where the wilderness still reigns

An old man takes a flower in his hand.

How I’ve watched you bloom and fade

and all the beauty you create

I’ll take with me that pleasure as we part.

– ‘We Had It All’, Someone Like You (1994)

NANA KELLEHER

Dan Joe’s wife, Margaret McTigue, came from a reasonably well-to-do local family, but her marriage to Dan Joe was not well regarded and her dowry reflected the disappointment in her choice to marry down. As a young woman she was sent to agricultural college in Tipperary, where, in addition to general agricultural studies, she specialised in butter- and cheese-making. I only learned of her cheese-making ability recently, and it may explain my own fascination with the craft. While a student at Ballymaloe Cookery School, I was hooked from our first cheese demo. The pleasure of working with the curd is sensational and I found it very therapeutic; little did I know then that my Nana Kelleher may have passed on her cheese gene to me. She spent her days churning her butter, making cheese, feeding geese and hens, tending to the livestock and forever cooking or baking in Bastible ovens over a large open fire, which was constantly aglow.

Every autumn, neighbours came to the house to help with the curing of the pig. It was customary to gift the help with cuts of meat as they departed. The wonderful saying, ‘We weren’t all one when you killed the pig,’ was often used and still is in some areas to remind certain houses of an oversight in such times of plenty.

The Feast of St Martin, or Martinmas, is celebrated on 11 November each year and was generally regarded as the date that all pigs be butchered and prepared for the winter. This date is also linked with ancient sacrificial geese and all sorts of darkness. My legend has it that St Martin invented the pig from a piece of beef fat. He gave it to a young girl, telling her to put it under a tub and turn it upside down and await further instruction. Being selfish, the girl split it in two and hid her own piece under a basin. The following day, a sow and twelve piglets appeared where Martin’s morsel had been placed, but as punishment, the girl’s sliver produced mice and rats, which ran off around the house and into the yard. St Martin then created the cat from a mitten, and sent it off to chase the vermin; to this very day cats continue to do his bidding – or so the story goes!

Every ounce of meat from the pig was used. The head was boiled to produce brawn, also known as head cheese, a terrine set in aspic. Sometimes the cheeks and jowls were removed, boiled and eaten as delicacies. Those traditions live on; for my own fiftieth birthday party, I cooked a pig on a spit and my friend and champion Tipperary hurler Nicky English phoned in a frenzy, saying he was delayed in town. ‘Mike, has anyone touched the jowls yet? If not, put my name on them! Make sure no one goes near them, I’m on my way!’ Sure enough, as soon as he arrived, he made a beeline for the pig’s head. He was a very happy camper as he sat back on his chair with a beer and a jowl. Maybe there’s something in them there jowls that’s good for the hurling.

Nana used both a wet and a dry cure. After a few days’ hanging, the pig was jointed and cured with salt; the following day, the moisture extracted by the salt was washed away and another coat of salt applied. This dry-cure process might take three to four days. A wet cure was a simple solution of salt and water in a barrel, left for days. The loin, shoulders, legs and belly were then hung from the rafters and used as required for rashers, bacon and Bastible roasts. Some were placed in the chimney breast for smoking.

The cured bacon hung from the hooks in the main room, protected by two or three strips of flypaper. That paper gave off a very distinctive sweet odour, and its colourful package always conjured up images of America for some reason. Perhaps they were part of a parcel received from rich cousins across the Atlantic.

Nana cooked everything from chickens, stews, bacon and cabbage to vegetables, to breads and cakes on an open fire in a selection of cast-iron Bastible pots that hung from a metal crane. She fried pork chops, homemade puddings and eggs on griddle pans which sat among the burning sods of turf. Hanging from the crane was a great big giant black cast-iron kettle, always full of water, constantly on simmer ready for the tae or the washing-up. Bastible cooking required great skill and experience. There was no thermometer to monitor the heat, and certainly no alarm clocks to signal the end of cooking – it was sheer skill. Her breads and sweet cakes were placed in the ovens, with hot turf spread on to the lid to ensure even heat distribution. There is a beautiful saying – ‘Never let the hearth go cold’ – so at bedtime, a sodden piece of turf was laid, burning slowly through the night to keep the embers warm. In the morning flames returned with the help of a poker and some kindling.

Most of the milk from their herd was transported by horse and cart three mornings a week to the local creamery. Nana always kept one bucket at home, covered with a tea towel. The separated cream became butter, and the rest we drank liberally. As far as we were concerned, the butter was our Nana’s only culinary weak spot. It was salt-free, and we all hated it with a vengeance. What was worse, we weren’t just subjected to it over our summer holidays on the farm; during winter months she would send four pounds of the stuff weekly to our home, and the sight of it on the table brought many sighs and moans, much to my mother’s chagrin.

Nana Kelleher was firm, very strict and fearless around animals. We often saw her chase away foxes or stray cats, but the best was her battles with the tiny field mice who were regular visitors to the cottage, searching for warmth and food. On one occasion a mouse hid in the scullery behind pots and pans. Nana stood there with her hawthorn stick, carefully removing the pots and basins one by one, until finally the mouse was exposed and made a dash for the opened door and his chance at freedom. As he sped past her, the swish of her stick sent him staggering across the farmyard, Nana in hot pursuit. Off he raced across the muddied track and to our delight reached the farmyard wall, where he disappeared into a crevice and off out into the safety of the L-field. Later that night during our bedroom whispers it was agreed that he would now be so scared of Nana he would never return. We all hoped he got home safe to warn his family and other mouse friends to stay well clear of the angry woman with the very big stick.

ANIMAL FARM

The excitement of our first morning of summer holidays at the farm each year is etched in my memory. The sun beaming through the window, the farm already in full flow with the jangle of tackle as Granddad prepared Charlie for the creamery run, Nana swooshing the geese over to the sandpit, hens clucking to the sound of cock-crow and the little calves bellowing at the distant trough.

After a quick wash in the light blue ironstone basin with its pitcher of freezing cold water we moved from the parlour into the heat of the warming fire, to eat a bowl of porridge and some homemade bread with that loathsome butter, thankfully offset by Nana’s beautiful homemade gooseberry jam. We then set off on the first of our many daily adventures. This vast open country playground was ours for the taking, and out there on the L-field, so named for its shape, we were anything our imagination conjured up: hurlers, soldiers, swashbucklers, farmers, truck drivers, Olympic runners, show jumpers, tennis players, Pelé or Pat Taaffe on Arkle chasing down Mill House for the Gold Cup.

Underneath the rows and rows of Scots pines that separated the cottage from the working farmyard was our very own battleground where we separated into little army corps, erected barricades and went to war with bundles of fallen pine cones. Occasionally a stone might be inadvertently introduced, and then the battle turned nasty; all bets were off when the first screams drew Nana from her busy day to scatter us away from the theatre of war, to hide in the hay shed and dream up our next escapade.

Charlie the horse, our best friend ever, was patient, passive, intelligent, hardworking and without doubt the most loved animal in the world. Whether he was resting or cooling in the shade, his ear perked at our calls, drawing him out of the haggard to amble his way to the top gate for a feed of apples and nuts with plenty tender loving care.

In the early morning we gathered the cows for milking. Some of the cows had pet names given to them by Nana and Granddad and each one had a personality of her own. Some were gentle to milk and others just lacerated you with their swishing tails. I am still convinced their massive eyes were laughing at each successful flick of the nape. The young calves were treated to nuts, and petted by all the children, unlike the poor geese who were taunted and riled into a frenzy until they lost their cool, dipped their necks and lunged after us in attack, hissing angrily as we ran screaming back into the safety of the hay shed.

Most of the farm chores were OK, but every now and then you pulled the short straw and had to clean out the filthy henhouses, or shovel the dung from the slurry pit into a wheelbarrow to be spread across a field at the back of the main yard. The worst job was clearing the ‘yallow weeds’, as Granddad called them. Rag weed or Ragwort was, and still is, a scourge on farms and regarded as dangerous to livestock, so every summer it had to be cleared. Fields were cordoned off and a concerted effort was made by the chosen ones to get every last stalk from the ground. A yallow weed day was long and extremely torturous.

THE MEITHEAL: THE GATHERING

The animals lived well on the farm, with a diet supplemented by the hay that we saved during the long summer months and stored in the barn which stood beyond the pine-tree battle line. The meadow was located a few miles away in an area called ‘the Slob’, which was, to all intents and purposes, a very large allotment shared by many local farmers. In early summer the community gathered with their scythes and methodically made their way through the meadows, cutting the tall grass. At intervals during those long working days, tools were downed and the ‘tae’ was served, with sandwiches, scones, tarts and ‘curnie’ cakes, or spotted dick as it was also called. My mother used to add a pinch of ginger, nutmeg or allspice to her cakes, which gave the bread a great colour and a sharper taste. Each house had its own version.

The bottle of tea was wrapped in old newspapers or tea towels to retain the heat. On occasion, a different, magic bottle that no one ever seemed to mention was passed around among some of the elders.

Weeks later when the grass was dry, a team again assembled to rake the hay into little bundles, and then into small cocks, or ‘trams’ as we used to call them. They stood about eight feet high and were secured by a hemp rope also known as a sugán, which was weighted down on either side with large rocks. Sometimes a sheet of plastic was secured at the top of the tram to prevent the rain seeping through. The hay was then slowly transported by horse and float back to the barn. The float, an exceptionally well-designed piece of farmyard machinery, was a flat rectangular platform trailer with two front-mounted rope winches controlled by three-foot wooden levers. The float tilted to the ground, ropes were tied around the tram, and winched from the field on to the platform. The weight of the hay then levelled the float, and once secured, off we went to deliver to the waiting crew at the hay shed. Along the road we might stop and chat to the neighbours, including the likes of ‘Great Weather’, who always greeted us with ‘Great weather, Dan Joe!’ come rain or shine, or ‘Winkers Kelly’, who never failed to hurl abuse: ‘Ya useless townies, ya!’ – always answered with ‘Go wan, ya big four eyes!’

The final trip of each week included a stop at Curry’s pub, where Granddad drank his bottle of stout and treated his lucky little helpers to fizzy orange and crisps. On the odd occasion we might stop at our cousin’s at McTigue’s post office, which meant a pack of Stevie Silvermints or a bar of chocolate. Those of us left behind in the haggard had to listen to the gloating and wait another day.

One morning the quiet of the farm was interrupted by the distant sound of an engine that grew louder and louder with each second. ‘That’s Pa Joe McMahon and his buck rake,’ my dad announced. ‘It’s over at Spellissy’s now, I’d say. Won’t be too long.’

Within a minute the roar of the tractor engine arrived, carrying a tram of hay on six large, pointed steel prongs. It dropped the load and was gone up the dirt road and out of sight in no time. ‘I suppose this will speed up the gather,’ Dad said with a hint of sadness in his voice. What had been weeks of drawing hay now took a matter of days. I remember a definite sense of sadness, though. The halcyon days were gone: no more trips to the meadow, no more float, no Winkers Kelly, or chewing the dry blade of grass as the world passed, and no more Stevie Silvermints after a long week’s work. It was progress for sure, but the buck rake also delivered the end of a certain magic that morning.

MICKY HANRAHAN

My other grandfather, Micky Hanrahan, was a jovial man. His family came from Fedamore in West Limerick and moved to Barntick in Clarecastle, a few miles from Ennis. He married Aggie from Labasheeda in West Clare, and they lived in a beautiful cottage on the top of the hill by New Hall Lake. The small farm was built on the edge of a rocky cliff with little growth, but it was a haven for their goats, sheep and a few head of cattle that roamed freely to forage the hazel or berry bushes. I always saw him as a reluctant farmer, as I somehow never really associated him with the land. He worked at the local pipe factory and left much of the farming to Aggie and his young family. Oddly enough I never really saw my own dad as a farmer either, although I have a vivid memory of looking on in dread and fear as he stood on top of a large reek of hay catching fork-loads from down below. Goats wandered freely around their farm amid the constant cackle of turkeys, and at the back of the cottage was an old West Clare Railway carriage which housed lots of chickens.