Полная версия

Beautiful Affair

My father smoked a lot but never drank. At sixteen he was caught drinking at a neighbour’s house party and a horrible uncle force-fed him beer slops until his face turned green. Some uncle! Dad never drank again, although in his last few months he confided that he sometimes regretted not going for a few pints with his family.

Dad was a home bird, and especially loved the garden, and most of all his shed. His shed housed everything imaginable for DIY, and was a great source of peace and fulfilment for him. One year, he made nine Christmas stables, one for each of the family, with hazel sticks collected from the crag at the back of our house. He painstakingly cut hundreds of sticks to size, fixed them side by side to form three walls, made a roof and thatched it. Each stable measured two feet by one foot with straw scattered on a flat sheeted floor, peopled with a set of religious figurines. A coloured bulb was pushed through the back wall with a lead and plug hidden from view. They were works of incredible patience, and without doubt the most beautiful Christmas gift I have ever received – and I a very lapsed Catholic.

When I was a kid, he helped my brother Kieran and friend Vinny McMahon to build a wooden table soccer game. As kids we often called to Carmel Healey’s games room in town, and as Kieran had become quite the champion, he had taken the notion to build his own for home practice. Dad built the wooden stadium from a sheet of plywood, measured to perfection, with two goalkeepers and twenty outfielders all made from half-inch heavy black tubing, fixed firmly to wooden rods fed through holes perfectly measured on the table walls. Two goal mouths completed the scene. A box of table tennis balls gave the neighbourhood many great days of entertainment, and the very enterprising Kieran and Vinnie made a small fortune by charging everyone a penny a game.

I spent a lot of time in the garden with Dad, growing spuds, cabbages, carrots, rhubarb, lettuce and spring onions, forever planning for the following year. I read a gardening magazine piece on how to grow the perfect carrot by sifting all pebbles from the ground to allow the carrot free passage to grow to perfection, so I suggested it to Dad. I knew by the ‘Oh holy God’ look on his face what he really thought, but he replied, ‘Whatever you think yourself, away with you a stór (a beautiful Clare term of endearment). I’ll get the screed, and you can start sifting away.’

I dug the appointed plot and painstakingly sifted about a square metre area free of all pebbles and rocks. I was exhausted, but I think Dad was even more exhausted looking at me. However, my efforts were rewarded with perfectly straight carrots – which tasted exactly the same as regular ones. I think I missed the rugged shape of the old carrots, so the following year we reverted to the traditional method, stones and all. I have come to really appreciate and understand his attitude, and what stayed with me from my life with him was his constant encouragement to follow an idea or a dream. He never saw any harm in attempting the impossible, even if it meant spending needless hours and hours sifting pebbles from a patch of ground. It was all about making the effort and doing your best.

At twelve I started playing my brother Ger’s nylon-strung guitar. A young Franciscan priest, Pat Coogan, had recently arrived in Ennis and was playing soccer with our local team, St Michael’s FC. He played guitar and gave me my first lesson. One day, I sat down on my bed and heard a crack: I’d shattered my guitar. To the day he died, Dad was convinced that I did it on purpose to get myself a better instrument. I denied it at the time, but in hindsight he may have been right because I’d had my eye on an Egmond steel-string guitar in Tierney’s music shop. I eventually bought the guitar, along with my first Leonard Cohen album and book of songs. I was besotted with Cohen and started teaching myself his guitar technique from a system included in the songbook. Every day after that I flew through homework to get to my bedroom to sing his songs. After about six songs, Dad would shout up, ‘Have you learned that song yet, Mikie?’ Yeah, Dad, thanks … You just don’t understand.

Despite the monotony, his encouragement never waned, and I even heard him reassure a mother distraught to hear that her son wanted to become a professional musician: ‘Sure, Mary, as long as he has a guitar on his back, he won’t go hungry.’

STRAUSS AND THE TULLA CÉILÍ BAND

When we were very young Dad bought a Philips record player and the most curious, eclectic collection of records imaginable. There was Strauss with the shimmering strings of ‘The Blue Danube’, the Tulla Céilí Band, the Dubliners with ‘Waxie’s Dargle’, Larry Cunningham, Donal Donnelly, Tom Jones, Doris Day, the Kilfenora Céilí Band and the Beatles. Our first record player was a turquoise blue, portable foldaway that looked like a suitcase. It had a turntable, a three-way speed switch for singles, albums and old 78s, two buttons, one for on/off and the other for volume, but that little box created the most incredible sounds that filled the entire house. I can still hear ‘Take me back to the Black Hills, the Black Hills of Dakota’ from Doris Day, with my mum’s beautiful soft voice singing along. Later, Dad bought a very fancy console-style stereo all in one, with radio, turntable, storage racks and speakers encased in a beautiful mahogany cabinet. Our record players were hardly ever silent and our record collection grew every week.

THE SUMMER JOBS

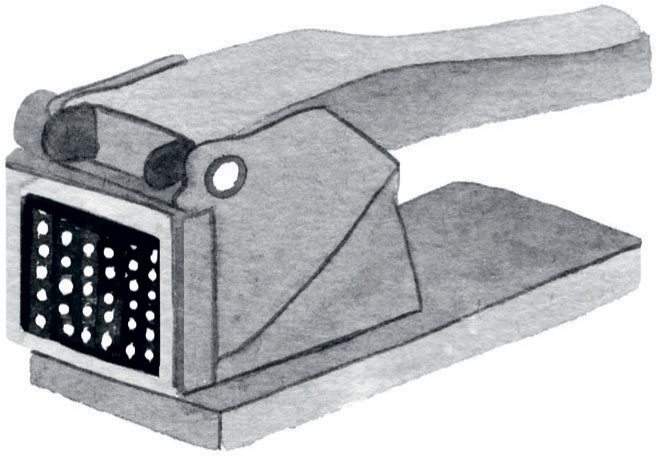

As soon as we reached our teenage years, we found gainful part-time employment at various shops in the town. I worked at Morgan McInerney’s hardware store in the market square, which sold everything from teapots to bags of cement. I was entitled to a staff discount, so all birthday and Christmas gifts carried a hardware theme. Mum’s were usually kitchen gadgets: a four-egg poaching pan complete with lid; a fancy cheese grater; a tomato slicer that required extra-special skills to avoid slicing fingers; and Dad’s favourite kitchen mate, the potato chipper, which he used every Saturday for our eagerly anticipated special treat. He loved that chipper, and we devoured each and every equally-sized chip it cut, the smell rising from the sizzling basket of Mazola oil, chips drained and sprinkled with salt, soaked in malt vinegar and served up with a good dollop of ketchup. Now that’s a food memory that’s hard to beat – unless you add a soft-fried egg.

Going to work at an early age was good for us, and my mum was delighted with the extra few bob. We worked all summer, Christmas, Easter and every Saturday during school terms. My brothers Joe and Adrian also worked at the hardware store, and Ger and Kieran worked in a shoe shop, which made runners the thing for Christmas morning. My poor sisters Gay and Jean were confined to barracks-cleaning and sweeping the homestead.

Work was not at all taxing as I recall. I spent much of my time tidying the many stores of cement, timber, paint and plumbing pipes. On Saturdays I had to polish and shine the proprietor Jack Daly’s silver Jaguar, and to this day I still want to own my own Jag. The rest of the day was spent serving behind the counter, or running errands for the staff, which took me to various locations around the town. One day I was taken by Mr Daly to see Joe Leyden, who had called in sick. Joe was a simple man who did odd jobs around the shop and spent the rest of his days sitting at the Daniel O’Connell monument in the middle of the town, watching the world go by. As we entered his house on Parnell Street a darkness like no other engulfed us. Mr Daly threw open the curtains and as my eyes readjusted, I reeled at the sight: hundreds of old newspapers piled high on an earthen cottage floor, a table in the corner with books, empty bottles, teacups and a vase of faded flowers. The kitchen was full of unwashed dishes and yet more newspapers and magazines. An open door led us to a bedroom where Joe lay moaning in pain. He was later moved to hospital and recovered to live another day.

Years later that visit was the inspiration for ‘Indians and Aliens’, a song about a very misunderstood young man who read accounts of the Trail of Tears march of American-Indian tribespeople across rough terrain that left many dead along the way, and of the massacre of the Lakota at Wounded Knee by the US Army. In a rage, he returned to his schoolhouse, a metaphor for those who instilled in him a deep-seated prejudice against the Indian nations. He burned it to the ground, and society, rather than seek to understand his troubled mind, shunned him and forced him into an institution. Joe, like the character in the song, was very misunderstood, and bore the brunt of many jibes from locals, young and old. I often wondered what went on in his mind as he sat on the monument looking down on the town. Many of us can relate to a degree; I was also that boy burning down the schoolhouse by the river. Mine had controlled my world through religious doctrine and fervour.

He was a simple man who loved Star Wars and John Wayne,

Lived in a little house, a little down and out, but that was his way.

Nightmared on Geronimo and the Empires of Doom

All alone in a little town, all he ever knew

Was Indians and aliens, Indians and aliens, coming for me and you.

– ‘Indians and Aliens’, What You Know (2002)

ARE YOU RIGHT THERE, MICHAEL, ARE YOU RIGHT?

On Sundays we jumped on an early bus to seaside Lahinch, which lies between Ennistymon and the majestic Cliffs of Moher. These days its ferocious waves attract thousands of surfers who want to test their skills on tough Atlantic breakers all year long. When we were kids, the great attractions were an amusement park of chair-o-planes, high swings, bumper cars, carousels and an outdoor swimming pool with a diving board that reached way up into the sky. The beach stretched for miles, and we crept through myriad sand dunes to spy on kissing couples. We ate boiled periwinkles and dried sea grass served in little chip bags from the vendors on the promenade, or instead settled on burgers and ice creams at the entertainment and games centre across the street.

THE BALLROOM OF ROMANCE

At weekends my dad collected tickets at the local dance hall, Paddy Con’s, later the Jet Club. The hall now operates as Madden’s furniture shop, and Michele Madden and her daughters protect the history and heritage of the building with pride and dedication. Its balconies, stage and heavily sprung hardwood floor are still intact. The memories come flooding back every time I stroll from balcony to floor, feigning an avid interest in some nest of tables or chaise longue on display. As I climb the stairs to the stage, I inhale a welcome breath of nostalgia – but I never feel alone, as I’m well aware that some of Madden’s other customers are doing the very same, soaking up the energy that lingers from this once vibrant ballroom of romance. I often helped Dad sweep the floors, stack chairs or clear out the dressing rooms, and constantly badgered him to bring me along to meet the bands as they arrived for the evening show. I remember meeting Butch Moore the year after he represented Ireland at the Eurovision Song Contest singing ‘Walking the Streets in the Rain’. I met all the stars of the day, Larry Cunningham, Brendan Bowyer, Dickie Rock, Margo, the Clipper Carlton, Gerry and the High-Lows, the Drifters, the Miami, the Cadets, the Premier Aces and my favourite of all, the Cotton Mill Boys. Of all the people I saw perform there, fiddler Sean McGuire stands apart. I still remember his breathtaking versions of ‘Hungarian Gypsy Rhapsody’ and ‘The Mason’s Apron’. I met him many times in later years and realised a dream when we shared a stage and a few tunes at the Ulster Hall in Belfast.

reproduced with kind permission of the Clare Champion

All I ever wanted was to be up there on that high stage. Whenever I call in to check out the latest furniture deals, I close my eyes and see a crowded hall, a sparkling mirror-ball casting its glitter across a pulsating dance floor. I can still feel that sinking sensation when a beautiful girl refuses or ignores your invitation to dance, or worse, when your pal beats you to the chase. As a young teenager I would play that hall on many occasions in a rock band called Effigy, and those nights at Paddy Cons ignited a flame within me that still burns.

THE GARDEN OF ROSES

As a twelve-year-old I harboured ideas of a religious vocation, choosing the Order of St John of God following a visit by a brother to our school on a recruitment mission. Three of us were taken to a seminary in Celbridge, County Kildare, for a trial retreat. It was my first time being so far away from home, and I felt isolated in that seminary. Even though there were lots of people moving around, sports fields surrounded by beautiful tree-lined avenues, large dormitories, lovely food, altars and lots of prayers, I still felt alone.

On my return, my mother and I discussed the visit and she insisted that I really think about what I wanted to do. ‘Mike, I hope you’re not doing this for me or your father, because that would not be right. If you don’t want to go, then please tell me, and that will be the end of it.’ When I told her I wanted to stay at home she said, ‘Good, that’s that, then.’

We never spoke about it again until many years later when she confided she was thrilled with my decision, as she dreaded the prospect of me living away from home at such an early age. Crucially, though, she reiterated that she would have supported me either way. Mum and Dad often pointed out possible obstacles but never ever put one in our way.

As a young teen I was a true believer, and very dedicated to the Catholic Church. I spent a lot of time as an altar boy in the local Friary. It was a beautiful place and most of the Franciscans were wonderful people. We had many visiting priests and brothers who came to spend time at the centre, and when I was about fourteen, maybe fifteen, a regular visiting Franciscan brother came to our house to ask my mother for permission to take me to Galway for a weekend retreat. He sat with my mother and grandmother drinking tea, talking God and Church and praising my work at the Friary. He blessed them both and followed me out to the hallway, closing the door behind him. In the privacy of the hallway he enquired about my girlfriends, their names and which one I liked best. He began poking and feeling around my genital area, asking me if I liked it. I felt trapped, and was extremely uncomfortable. I didn’t know what to do. He continued until I managed to get to the front door. I begged him to leave me alone. As he pushed past, I noticed a lot of dandruff on the collar of his brown robe. That’s how I still remember him today. I felt ashamed, and almost dirty. I made up some excuse for turning down the trip to Galway, and I left it there in that hallway for years and years and tried not to think about it. Years later, I was walking down Abbey Street in Dublin when I spotted him coming towards me. I panicked, and hid in a doorway. As he walked by, all I noticed was the dandruff. It was still there. I wanted to scream at him, but I had no voice. I was still scared, or perhaps ashamed. I was twenty-one years of age. I never saw him again.

We all knew that certain priests in the parish were ‘dodgy’ – many altar boys relayed stories of hands slipping into their trousers. Some of us eleven- or twelve-year-olds were once brought into the office one by one by a Franciscan priest, who said he was to show us some ‘personal hygiene’ habits. He said our parents had requested it, but that we were bound to silence, as they were far too embarrassed to broach the subject further. Best keep it to ourselves. Yes, Father. Among ourselves we knew there was something wrong. We had our names for them, and we tried to steer clear of their advances and warn the younger boys, but the overriding reality was that we had a dedication to a church that controlled every aspect of our lives – and that’s where their power lay.

I have never forgotten those instances of abuse, and unfortunately to this day I still harbour a deep sense of personal responsibility for allowing them to have occurred in the first place. I have had to wrestle with that guilt every time it finds its way to the surface. I certainly felt betrayed. Thankfully, I do not own that shame any more. Healing is powerful in that regard.

In 2001 I felt compelled to write and record a song called ‘Garden of Roses’ after all the harrowing accounts of cases of child abuse by religious orders, including one particular cleric close to home. Deep down I knew I had to speak to Mum about the song’s imminent release, and if I could, talk about my own experience. Words will never truly describe that profound moment between a mother and her son. We talked and cried a little but together crossed over into a very special place of understanding. I felt such a deep sense of relief because I knew she understood my hurt, and I in turn empathised with her own very personal pain.

In the garden of roses where you came by,

Beautiful roses, the eyes of a child

In your secret desire you cut it all down.

Now the petals lay scattered on tainted ground

In the garden of roses, beautiful roses.

Hot Press founder Jackie Hayden called me after hearing the song; he wanted permission to include it in his book In Their Own Words, a compilation of personal stories from abuse victims in the Wexford region to support the Wexford Rape Crisis Centre. I was invited to perform at a few very powerful and moving healing services where the song found its true home. The song continued to make an impression with listeners as the revelations kept coming, as it was included in a 2011 book, The Rose and the Thorn by Audrey Healy and Don Mullan. In the autumn of 2018, I was invited to perform the song once again, but this time at a day of remembrance for Ireland’s lost children at the site of the mother-and-baby home in Tuam in County Galway. It seems we have come some way from those terrible days of darkness. I certainly hope so. May the healing continue.

Now your temple has fallen, the walls cave in.

We witness the sanctum in their evil sin.

But a river once frozen deep in the mind

Flows on like a river should in the eyes of a child

In the garden of roses, those beautiful roses.

– ‘Garden of Roses’, What You Know (2002)

FAREWELL TO DAD

My dad died before the avalanche of abuse stories arrived, and I know he would have been shocked to the core. He was a very religious man, and like many of his generation lived by church rules and served without question. I have no doubt that I could have spoken openly to him about writing ‘Garden of Roses’. He would have listened and offered comfort, of that I am certain. His death in June 2000 had a profound effect on my life and my songwriting. Two years later I released the album What You Know. The title of the album is an expression he used for almost everything that he could not instantly put a name to. If he wanted you to get a paintbrush from the shed he might say, ‘Mikie, will you get the what-you-know from the shed, I want to finish that bit of painting. It’s in the box beside the what-you-know, the screwdrivers.’ You had to be on his wavelength, but we usually were.

A songwriter friend of mine once wrote of his dad’s passing, ‘The greatest man I never knew lived down the hall.’ It was such a sad song. I am glad to say I knew mine very well and we shared many great times together. When he was diagnosed with cancer, he was given nine weeks to live. Such was his strength and determination he lasted almost two years and faced it with great courage. Thankfully, I never had a slate to clean with him so we carried on as normal and tried our best to make the journey comfortable. His funeral was one of the biggest Ennis has ever seen, a testament to his wonderful personality and selfless generosity. He sits on my shoulder for every gig and I love to talk about him. He never got to see me in chef whites but I have absolutely no doubt it would have pleased him and he may have turned to Mum and said, ‘Sure, Mary, once he has a frying pan in his hand, he won’t go hungry.’

Take away the sad and lonely, all the trouble that surrounds him,

Firefighter won’t you come …

CHAPTER 2

DOOLIN

See all the doors swing open,

Your life’s unfolding before your very eyes,

Such a strange affair,

Walk in around, come into the sound,

Forget you’re down, feel the air, beautiful affair.

– ‘Beautiful Affair’, Light in the Western Sky (1982)

McGANN’S PUB, DOOLIN, 2018

I’m sitting on an old bench in McGann’s pub on the rugged north-west coast of County Clare. The walls of old faded photographs come to life, evoking powerful memories of a bygone era. I feel this swell of emotion, exalted and suddenly aware of the significance of these amazing colourful characters who taught me so much all those years ago. Doolin, my gateway from innocence, where the petals of youth opened wide to drink in their first rays of glorious sunshine.

Doolin sits on the edge of the Burren, that mystical landscape of limestone rock and rugged terrain where creative energy finds comfort and a true home. They say that Tolkien was inspired to write The Lord of the Rings after spending time here; Dylan Thomas married a local woman and lived in Doolin for a time; George Bernard Shaw and J. M. Synge often wrote of its beauty. In the early 1970s a new generation of free spirits arrived in Doolin from faraway places, and though some passed on through, many remained and integrated to develop a very special community. Today that community thrives and continues to provide a haven for travellers, lovers, dreamers, musicians, poets and singers. It feels so good to be back again, and it feels like I’m home.

TOMMY McGANN

In 1976 Tommy and Tony McGann returned from America and bought a run-down pub in a very quiet and neglected area of Doolin about a mile east of the action on Fisher Street, where Micho Russell held court at O’Connor’s pub, singing and playing the whistle, entertaining fans and visitors from all over Europe. The pub had been owned by two Americans who had run out of money, forcing the bank to take over, and within a couple of years the building had fallen into disrepair. Their father, Bernie McGann, sold a little plot of his land in Kilmaley to finance his sons’ venture. Neither had any previous experience in the pub trade, which resulted in much trial and even more error in the early days. Although Tommy’s management skills were almost non-existent at that time, he found a way through, with a charm that came to define him and set him apart throughout his short life.