Полная версия

Trajectories of Economic Transformations. Lessons from 2004 for 2024 and Beyond

In 1990—1991, the logic of events, prompted by the pressure of the concepts of economic romanticism and populism, led to a state of the national economy that can be characterized as close to collapse. In 1990, there was an abrupt shift from a positive to a negative trajectory in the production of GNP and national income. The imbalance of economic relations of almost all enterprises has exceeded the critically permissible level. The economic efficiency of the development of the material and technical base of the national economy has become not just declining, but negative.

One of the serious reasons for all this is the tendency towards the destruction of statehood. The economic reality that took shape in 1989—1991 became a synthesis of the worst features inherent in both the centralized model of management (its cumbersomeness, multiplied by the elimination of almost all incentives for power coercion) and the market mode of interaction (atomism, which develops into anarchy, the barter-speculative nature of relations, and the monopoly of the seller in relation to the buyer).22

The author of the article mentioned in the footnote noted that the contradictions that became the subject of the analysis stemmed from the fact that “the main landmarks of reforms were the forms, not the content, of economic development. The objective criterion of progress, which is limited to the dynamics of the productive forces of society and the satisfaction of the material and spiritual needs of the population, has been lost.”

Exploring Alternative Paths of Transformation

The Soviet Union and its national economic complex collapsed (if we single out purely economic reasons for this) precisely because of the loss of sources for the sustainable implementation of the process of expanded reproduction of its economy. Extensive sources of reproduction were exhausted, and intensive factors could not be used because they were concentrated in the “non-economic” defense sector of the economy.

There is no doubt that the economies of Russia and other countries of the former USSR were to undergo radical transformations. What kind of transformations would be optimal?

At that time, the most active part of the initiators of the transformations had no doubts that it was necessary to quickly form a market-type economy, the prototype of which was the economic models of the most developed Western countries. At the same time, theoretical positions that were based on the belief in the possibility of socialist principles of economic management, if they could be implemented in some form “cleansed” of the negativity of Soviet practice, also remained widespread. They, however, were “on the defensive” and increasingly retreated under the pressure of the radical market direction of reforms. It must be admitted that the direction of reforms towards the development of market relations was absolutely justified in principle. But this does not mean that there was no alternative to the specific paths of reform chosen.

Today, from the standpoint of the experience gained on the path of contradictory market transformations, it is becoming more and more obvious that ideological approaches are an extremely unreliable background for the choice of state decisions. The old communist ideology was a brake on effective entrepreneurial behavior in the economy, and, therefore, a brake on ensuring the country’s highly competitive position. But then a new ideology rose to the Olympus – the primacy of market individualism, and it proved to be intolerant of other approaches and aggressive. With unusual peremptoriness, decisions and proposals that did not correspond to the new ideology were labeled as “non-progressive”, “non-market”, and “conservative”, which was enough to remove them from consideration without delving into the content from the point of view of economic performance.

Was it then possible to carry out effective transformations without completely rejecting the signs of socialism, but, on the contrary, deriving certain advantages from them? It is hardly possible to answer this question today. Reasoning in the style of the subjunctive mood is always insidious. But it would also be a mistake to abandon any analysis of possible variants of socio-economic systems with components of relations of the socialist type.

Socialist and communist principles, which have been greatly discredited by the practice of the USSR, cannot simply be destroyed by some other ideology as fundamental values that attract many people. There is no reason to believe that they will not be in demand again and again by humanity in some respects in the future. Nikolai Berdyaev, one of the first and most profound critics of the model of socialism that developed in Russia after the October Revolution, remarked that “the movement towards socialism, understood in a broad, non-doctrinaire sense, is a world phenomenon” and that “it is not for the defenders of capitalism to denounce the falsehood of communism.”23 It is no coincidence that many ideas and principles of communism coincide with the universally recognized principles of decent human behavior, which are enshrined in the dogmas of the world’s major religions.

The recent deterioration of relations between the countries of the world in claims to limited natural resources and the inevitable disillusionment with the models of absolute individualism on which Western prosperity was nurtured, has brought many thinkers back to the values of collectivism. An additional argument is the steady dynamism of economic development in China, a country where socialist principles continue to color the entire system of social relations while at the same time actively spreading creative market mechanisms.

Unambiguous answers to the question of which model of economic and political system will be acceptable to the entire world community can hardly be found now. But the fact that this model will not be purely capitalist in the Western version in the foreseeable future is already recognized as true by objectively thinking researchers. The search for answers in terms of combining the motivations of market individualism and socialist collectivism will inevitably continue.

Chapter 4. Radical Reforms: Concepts, Consequences, Challenges

The idea of radical reforms, which set the tone for the transformation of the economic system in Russia, was the result of a collective awareness of the need to give our economy and society a new dynamism. It seemed that these transformations would create a scope for economic progress that would provide benefits for all. It is this national economic interest that became the driving force and justification for the initiation of radical economic and political reforms. And it was in anticipation of improvements for all that society embraced the ideas of transforming the country.

The reforms were aimed at rapid systemic transformations that were supposed to change the entire structure of motivations, increasing the interest of enterprises, savers, banks, and managers in entrepreneurial strategies leading to high efficiency and income growth for all. But, if we recognize this as the starting point of the public choice made, then the assessment of the results of the reform plans should be carried out with the expectation of adequate socio-economic criteria.

A Bold Start: The Early Phases of Reform

It is believed that market economic reforms in Russia began to unfold at the end of 1991, when a team of young, educated, and radically transformative ministers was assembled in the government under the patronage of President Boris Yeltsin. As early as January 1992, bold measures were taken on the so-called shock therapy method. Control over prices was lifted, channels for the implementation of foreign economic relations on an entrepreneurial basis were wide open, a policy of all-round denationalization of the economy and privatization of state-owned objects was announced, etc. Almost at the same time, the existing money overhang in the retail market was removed, shortages of goods and queues in stores were eliminated, and the shelves were filled with imported goods that were previously unavailable for free sale.

At the same time, it was found that the prices of goods and services rose abruptly, at a rate that was many times higher than the rate of increase in production. Wholesale prices for cement, for example, in January 1992 increased by 6 times compared to December 1991, and by 8.4 times by January. Daily output was 99% by December and only 89% by January 1991. The shortage of goods was eliminated by a sharp decrease in the effective demand of the general population and enterprises.

The reversal of the events of the reforms of 1992 and subsequent years has been sufficiently described in the literature. The courage of the young reformers at that time was based on the desire to get rid of the shackles of the stagnant past as soon as possible and was fueled by the conviction that it was the radical version of economic liberalization that would lead to the rapid emergence of a workable market economy with automatic advantages over the Soviet economy. The realities, as we know, turned out to be much more complex than desires and hopes.

Measuring Success: Two Dimensions of Reform

The results of the reform efforts can be assessed in two main ways. The first is the final economic and social results recorded by statistics and felt by the population. These results are determined by the scale and rate of growth of the social product and shifts in the standard of living of the people. The second section is the institutional changes that mark the formation of a new economic system.

It is the second aspect that has been brought to the forefront of public attention during the first very long stage of reforms. The denationalization of the economy, privatization, and the expansion of all kinds of entrepreneurial principles were conceived as the most important directions for the formation of a new structure of institutions and a new economic climate. And quite soon in this respect it was possible to note many remarkable processes in the economy that strongly influenced the structure of economic interests:

1. Shifts in the structure of ownership, the multiplicity of interacting economic structures.

The multi-structuring of the economy has become a reality. It is known that the economic structure is a certain type of production relations that encompass a significant part of the economy and is capable of relatively independent reproduction. At the heart of every economic structure is first a certain type of property. After 1995, more than 70% of Russia’s GDP began to be created in the non-state sector. In 1994 this share was 62% and in 1993 – 52%. Especially characteristic were the changes in the structure of retail trade turnover by form of ownership. In 1991, 33% of Russia’s total retail trade turnover was sold through non-state forms, while in 1992 it was 59%, in 1993 it was 77%, in 1994 it was 85%, in 1995 it was 87% and in 1996 it was 91%.

2. A new influence of demand on the economy, turning it into a real structure-forming factor.

3. Openness to the outside world of the Russian economy as a whole and all its economic entities, ensuring integration into globalization trends.

4. The new role of money. Turning money into a short-term resource is most attractive to businesses, banks, and households.

5. Significant weight of large owners of financial capital in the relations on the formation of economic policy in the country.

These changes were carried out in a very contradictory way, but they were milestones in the ongoing transformation of the Russian economy into a market-type economic system. And it was this last aspect that the official authorities and the relevant media emphasized when it was necessary to report on reforms.

Socio-Economic Indicators of Success

As for the first cross-section of the effectiveness of reforms, related to the dynamics of real socio-economic indicators, it was not in the public eye. The parameters of GDP, industrial and agricultural production, real incomes of the population, etc., did not appear in the reports on changes in the Russian economy. It is difficult to find a satisfactory explanation for this circumstance (except perhaps the desire of the authorities not to disturb society in the hope of A quick turn for the better), because the dynamics of almost all socio-economic indicators were consistently negative.

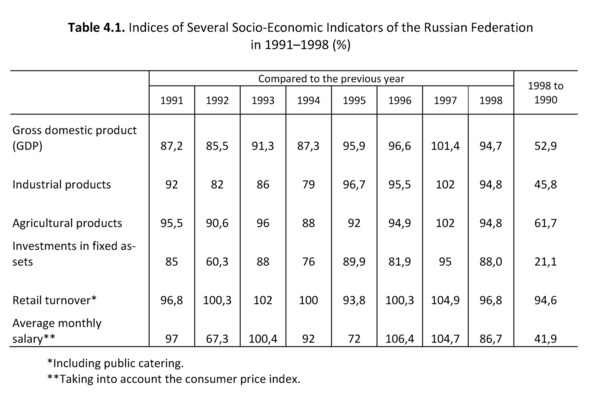

As can be seen from Table 4.1, GDP, industrial output, agricultural output, and capital investment in the economy fell almost continuously until 1998. At the end of the period under review, compared to the pre-reform year of 1990, GDP was less than 53%, industrial output was 46%, and investment in fixed assets was only 21%. Average monthly wage by the consumer price index was only 42% of the pre-reform level. The dynamics of retail turnover indices were flatter (less declining), but it should be noted here that, despite the abundance of goods in stores, the physical volumes of trade turnover in 1998 were less than in 1990.

Attempts by some analysts to draw attention to negative socio-economic trends were drowned in a stream of assertive praise of the chosen course. Economic recession was seen as the inevitable price to pay for getting rid of the evils of the past. This view was persistently introduced into the literature covering economic transformations. And even today, there are stories in serious publications aimed at proving the idea that the reform recession in the Russian economy (in 1991—1998) was Not only is it inevitable, but it’s not too big either. For example, in one of the articles in Ekspert, to the question “what did we (Russia) lose as a result of the victory of liberalism in the economy,” the authors give the following answer: “From an economic point of view, exactly as much as we should have lost,” because, they say, “most of the Soviet economy that Russia inherited was not viable.”

To make the conclusion convincing, comparisons are made with the economic recession during the Great Depression of 1929—1933, which amounted to about 30% in the United States. Russia, according to the article, lost 40%: “more, but not fundamentally more.” On the other hand, according to the authors, the radicalism of economic freedom has brought thousands of super-qualified people to the capital and labor market, which “has not been seen in any country in the world.”24 Such assessments probably have the right to exist in the press. However, a comparison of the effectiveness of two processes: the Great Depression, this natural disaster in the eyes of the US government and public at that time, and a conscious policy of reform in our country, it still looks very extravagant. If one of the politicians of the United States had declared then that the Great Depression was a planned reformation action, it is unlikely that he would have been in good luck.

Ideological Confusion: Goals without Clarity

However, it would be unfair to attribute the unsatisfactory approach to launching market transformations to the government of young reformers alone. The general situation of the time in and around the country was based on a mixture of the reformist romanticism with the conservative pressure of what George Soros defined as ‘market fundamentalism.’ Blind faith in the miraculous efficacy of institutional market changes somehow dominated the worldview of many politicians who entered the arena of the country’s political life at the stage of Gorbachev’s perestroika. And it was this cohort of politicians, in alliance with superficial publicists, who laid down in our society unverified ideological imperatives, which largely determined the course of reforms for a long time. The criterion of transformation has moved from the field of economic performance to the realm of slogans and ideological clichés. For example, the statement of one of the politicians of that time (E. J. Vilkas, Chairman of the Commission on Social and Economic Development of the Union and Autonomous Republics, Autonomous Regions of the Council of Nationalities of the USSR Supreme Soviet) during the discussion of the draft plan and budget for 1990 is very typical: “The progressiveness of any economic measures today is assessed by one criterion: to what extent it helps the market to establish itself.”

As a result of a multifaceted analysis of the initial stages of economic transformations in the country, Academician Nikolay Fedorenko rightly noted: “The main root of the failure of Russian reforms is buried in the fact that Russia entered the crucial stage of the transition period without a targeted program for this transition!”25

The absence of a public program for the transformation of the economic system with clearly defined goals at the very beginning of the reforms can be explained by the lack of time of those who took up the transformations, and the sharp political struggle between supporters and opponents of changing the economic system. However, all subsequent (after 1991) reformation steps took place under conditions of almost complete monopoly on the conceptual content of the transformations. This monopoly belonged to those in power. This means that it was the government of those years and the forces behind it that should be considered fully responsible for both the development of goals and the implementation of economic reforms. In the end, the responsibility should be shared equally by Russian society as a whole, which allowed the uncontrolled development of events.

The Human Factor in Economic Transformations

Let us draw attention to two fundamentally important conclusions made by international experts based on the analysis of the practice of market transformations in a large group of countries. Both observations relate to the human factor of transformation, or more precisely, to the socio-psychological side of managing major changes in society26.

First, the beneficiaries of reforms must set the goal of compensating the losers as much as possible. Without such motivation of the initiators of reforms, the transformations do not turn out to be attractive to society and will eventually either stall or lead to violent social conflicts.

Secondly, the leaders of the reforms in the country become such and gain authority only since they give their people a sense of ownership of the reforms, instilling confidence that the reforms were not imposed from the outside. They should take care to maintain a feedback mechanism that allows for timely adjustments to the content of reforms. To this end, broad discussions on key policy areas and priorities are usually ensured. Every effort should be made to create an atmosphere where people can be heard.

We must admit that both conditions were not even minimally met in the course of reforms in Russia. And if we talk about the first of these points, then we must admit that the task of social guarantees for the weak and “losers” was not only not put at the forefront but was simply ridiculed by many ideological leaders of reforms. As a result of this attitude, a colossal differentiation of society in terms of wealth and social status unfolded incredibly quickly.

This can be seen in a variety of parameters that characterize the structure of our population in terms of income, consumption, savings, property, etc. Academician Dmitry Lvov characterizes our Russia today in two of its images – rich and poor. “Rich Russia is home to about 15% of the population, which accumulates 85% of all savings in the banking system, 57% of cash income, 92% of property income, and 96% of foreign currency spending. In Russia, 85% of the population lives poorly. It has only 8% of property income and 15% of all savings27.

In 1990, the USSR ranked 33rd among all the countries in the world on the Human Development Index, at its worst, and Russia, which had already undergone reforms, ranked 63rd at the beginning of 2003.

Privatization in the Structure of Reforms

The institutional side of the transformations was dominant throughout the entire period of reforms, and the privatization of state property became the central point in it. This, by design, should lead to the emergence of more efficient owners. In fact, the question of efficiency in its generally accepted sense did not arise at all during privatization. The organizers of this process were dominated by two aspects of motivation: 1) the distribution (almost free) of the most attractive pieces of property among the most active figures of the reforms; and (2) the final burial of social property as a phenomenon and socialism as a system of economic management.

Indicative is the admission of Anatoly B. Chubais, who was its chief manager during the main stages of Russian privatization, in one of his interviews in 2002. Speaking of the goals of privatization at the stage of the loans-for-shares auctions, he emphasized that “there was a singular task at hand: creating large capital that could prevent the return of communism in Russia. Ninety-five percent of the task was political and only five percent is economic.” Yes, Chubais admitted, “one can make fair claims to the procedure of these transactions from the point of view of classical economic theory. But large-scale private property was created in the country in a very short time.”28

As we can see, economic efficiency was in fact of minimal importance in the acts of privatization of state property. But the political emphasis emphasized by Chubais as the dominant of privatization should probably be regarded in a wider range of motives than just the eradication of communism. Rather, behind this political slogan there is a very pragmatic motivation of a narrow stratum of people who received a gift of a huge amount of money in a short period of time property, to prevent its new redistribution.

As for the interests of society, which, by definition, must be protected by the state, they were pushed to the fore in the course of privatization – against the background of the private interests of the established oligarchs, as well as powerful shadow figures.

Here is just one aspect of the losses suffered by Russian society (represented by the state) from the distorted orientation of privatization, which is noted over time by Ilya Klebanov (then Minister of Industry, Science and Technology of the Russian Federation): “I consider it a big mistake that during the privatization of defense enterprises, the state did not value its intellectual property in any way. In fact, it ceased to own the rights to developments that were created with state funds and always belonged to the state. It simply took it out of its pocket and, saying ‘take it’, gave away its property for free. That’s wrong… Together with the Ministry of Property and independent appraisers, we conducted a study of several private defense enterprises and found out that all their capital, machine tools, real estate, etc., is only ten to fifteen percent of the amount that this enterprise would be worth together with intellectual property. It turns out that the defense industry was sold on the cheap.”29

Hasty steps to eliminate the leading role of the state in such spheres of activity as the production and sale of wine, vodka and tobacco products had an even greater impact on the bleeding of the national economy. It is known that revenues from these sectors of the economy have almost always been extremely significant for the state treasury. It is no coincidence that the problem of the “vodka monopoly” was unequivocally solved by the state in its favor back in tsarist times. Concessions in favor of private business in the field of wine and vodka products, cigarette and tobacco products, medicines, etc., have become key miscalculations of state economic policy. In the full sense of the word, they “slaughtered the chicken” that laid the main “golden eggs” for the state budget. It is impossible not to notice that the decisive beginning of these steps was set within the framework of the USSR, during the period of “perestroika”.

The outward amorphousness of the goals of economic transformation in Russia had its reasons. The absence of clearly expressed goals of reforms from the standpoint of society was primarily in the interests of the shadowy inspirers of the processes of breaking the old order. In the context of the blurring of strategic goals and in the absence of institutional constraints, it was easier to achieve the redistribution of the main parts of the previously social wealth, efficient capacities, and natural resources in the clearly defined personal interests of the new “elite,” which was locked in several positions with the criminals.