Полная версия

Trajectories of Economic Transformations. Lessons from 2004 for 2024 and Beyond

The Cost of Reform Programs

Criticism of the actions of the reformers’ government on the pages of the scientific press is quite often and rightly built around the thesis that there is no clear program for the transformation and development of the economy. Official circles usually respond to this by referring to the existence of several government economic programs related to the implementation of market reforms. Yes, there have been and continue to be such programs covering periods ranging from one to 4—5 years. Options have also been developed long-term socio-economic programs (for example, the well-known program of German Gref). However, none of these programs had the scope and status of a national strategy for socio-economic development. And the Gref program (claiming to be a strategy) was not even officially published and remained a semi-draft. It is impossible to name a single program document where the ultimate goals of economic programs would be presented in the form of reasonable parameters available for public scrutiny and would be supported by balance sheet calculations linking effects and costs in time and space.

The lack of a clear strategy for economic transformations was aggravated by the fact that there was no objective monitoring of reforms from the standpoint of results, and the government did not have the desire to self-critically evaluate its reform programs and actions. Meanwhile, there were numerous reasons to do so in a timely manner. It was necessary to at least analyze the assessments of qualified experts from the outside, if there was any distrust of critics inside the country. Here are some of the public assessments of the course of economic reforms in Russia, made by foreign experts whose reputation is beyond doubt.

For example, Joseph Stiglitz, the world-renowned economist and the 2001 Nobel Prize winner in Economics, in his analytical report Macro- and Microeconomic Strategies for Russia prepared jointly with David Ellerman, put forward very serious critical observations30. Subsequently, Stiglitz has developed these observations in articles and in a book on the contradictions of globalization that has received worldwide resonance31.

Let us cite a few excerpts from the above-mentioned report, because they were made at a time when there was an opportunity to correct many things. “Russia’s experience of transition from communism to the market has turned out to be much more complex than it seemed a decade ago. The increase in prosperity promised by the market did not materialize; moreover, GDP fell by more than 50%, and the share of the poorest population increased from 2% to 50%. It is necessary to recognize these facts and outline a program for the country’s exit from this state. Today, ten years later, we have inherited not only a new young emerging class of entrepreneurs, but also an even faster growing mafia. The state as an institution violates the social contract again and again, fails to fulfill its promises, and becomes an instrument for private profit at the expense of most of the population. At the same time, only a few are becoming fantastically rich, and most of the population is sliding deeper into the abyss of poverty, and the cynicism in relations with the state and the law is greater than it was a decade ago.

Many hoped that privatization itself, no matter how it was done, would create a demand for an institutional infrastructure that would conform to the market economy and the law, when the all-powerful hand of the hapless state would be replaced by the invisible hand of the market. However, there is neither economic theory nor historical precedent to support such hopes. Only the middle class in the process of its development creates a need for such institutions, and in the last decade there has been the destruction of the middle class in Russia and the creation of a new, more concentrated oligarchy that is not interested in the rule of law, healthy competition, and a fair bankruptcy regime.

The focus on the redistribution of property has diverted attention from the creation of new businesses. The way privatization was carried out did not pay enough attention to the management of firms and did not encourage the creation of new enterprises.”

The authors criticize the prevailing views on the role of the priority of anti-inflationary policy. “Attempts to strengthen the price mechanism by suppressing inflation,” they write, “may have the opposite effect. In addition, there is a view that if there are barriers to lower wages and prices, then moderate inflation is even desirable. Since transition economies are particularly in need of adjustment, the ‘optimal’ level of inflation may be higher than in other economies. The experience of the countries of Eastern and Central Europe shows that it was not the countries with the lowest inflation that developed the fastest… Wherever inflationary paranoia has contributed to the clampdown, macroeconomic policy appears to have played a significant role in the economic downturn.”

Some of these estimates, such as the arguments about inflation, can probably be argued with to some extent. However, in our opinion, it is inadmissible to consider the multilateral critical analysis of the above-mentioned work as some insignificant circumstance that allows it to be ignored. For my part, I tried to convey this position to the Russian public and the government as persistently as possible, but without a proper reaction32.

In addition, this material contains not only criticism, but also practical constructive conclusions and rational proposals. Thus, the authors believe that at the current stage in Russia, “the following macroeconomic strategies are needed:

– recognition that the country needs a growth strategy and should not focus only on financial stabilization;

– acknowledging that the current large-scale non-payment of taxes (as well as other direct and indirect obligations to the state) provides a unique opportunity to correct some of the mistakes of the past decade;

– recognition of the need to restructure the economy from top to bottom, through the creation of medium-sized and small enterprises that emerge anew or by spun-off from large ones;

– recognition of the need to build a resilient social democracy that can revive social capital.”

Nicholas Stern, the World Bank’s chief economist, has also published a rather critical assessment of the key stages of Russia’s reforms. Here are excerpts from his article: “The reformers ‘gifted’ ownership and control over enterprises to ‘their people’, insiders – nomenclature directors, who were the real owners of the enterprises. They also managed to forge relationships with a new class of oligarchs who made their fortunes either in the final years of the old regime or during the period of inflation that became a feature of the early years of the transition. The oligarchs have taken over the most lucrative sectors of the Russian economy. The reformers depended on the support of the oligarchs and, using a highly dubious scheme of mortgage auctions, transferred additional state assets to these tycoons. At the end of the article, the author noted that an important task of his organization (the World Bank) “is to help Russia” and that “today Russia has a chance to start all over again.”33

Post-Default Economic Shifts

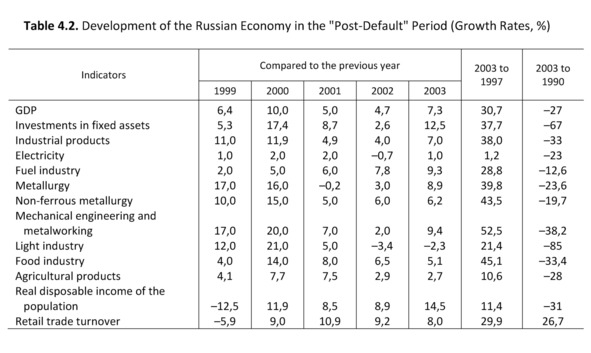

Analyzing the course of economic transformations in Russia, it is impossible not to single out the change in economic dynamics that took place after 1998. Since 1999, Russia has switched from negative parameters of GDP change to the dynamics of economic growth (Table 4.2). Surprisingly, the default of August 1998 helped to mobilize our economy.

The economic growth rate in 2000 was particularly significant due to the sharp fall of the ruble against the dollar after the default and a significant improvement in the foreign economic situation for Russian exports in the commodity markets, especially oil and gas, and a few other favorable circumstances. Economic growth continued in 2001—2004.

In December 1998, inflation was recorded at 84% and in 1999 it was 36%, but in 2000 and 2001 the consumer price index fell to 20%. There was a steady increase in gold and foreign exchange reserves in the Central Bank of Russia: if in 1999 they were at the level of $12.5 billion, by the end of 2000 – $28 billion, then at the beginning of 2003 – $50 billion, and in mid-2004 – $65 billion.

In Table 4.2, along with the data on macroeconomic indicators for the favorable years (1999—2003), a comparison of the indicators of 2003 and pre-reform 1990 is given (see the last column of the table). As we can see, the growth indicators achieved over the past 5 years are far from compensating for the recessions that were allowed during the previous period of reforms. In 2003, GDP was (in comparable prices) lower. 27% more than in the base year of 1990, industrial production by 33%, and agricultural products by 28%.

The situation is particularly destructive in mechanical engineering (-38% of the 1990 level) and in light industry (-85%). But the fuel and energy sectors, some managers of which are inclined to present their activities as “saving” for Russia, also have nothing to be proud of, because the decline in them was significant (-13%), but at the same time there was a significant increase in industrial and production personnel. Thus, in the first ten years of reforms, electricity production decreased by one quarter, and the number of personnel in the industry increased by 1.5 times. The volume of oil production amounted to 60% of the 1990 level, while the number of employees increased by 1.9 times.

It should be noted that investments in fixed assets remain at an extremely low level. Their volume in 2001 was 3 times lower than in the pre-reform year of 1990.

In 2003, real disposable incomes were almost one-third lower than in the pre-reform year. Moreover, according to this indicator, the gains achieved in 2000 and 2001 did not compensate for the losses incurred in the year of default. As of 2001, the share of the population with incomes below the subsistence level exceeded 30%.

Thus, the economic results of the entire past period, which is identified with radical reforms, do not look satisfactory even against the background of the rather favorable years of 1999—2003. Therefore, doubts that the current economic course has the necessary potential to reach the boundaries of the people’s well-being and the development of production soon, which would become compensators for the previously incurred losses in the economy, are more than justified.

The high levels of 2000 cannot be replicated or sustained, and economic growth rates in 2001 and 2002 were significantly lower. Further trends were in fact determined by the external environment in the energy markets, which is by no means a sustainable growth factor.

Professor Jacques Sapir, Director of the Higher School of Economics of Social Sciences in Paris, said: “After the 1998 financial crisis, Russia experienced significant growth over the next three years… This growth came as a real surprise to most Western observers. The Russian government, born out of the 1998 crisis, did not enjoy the sympathy of Western observers, who were more lenient with previous governments. Recall that in April 1999 the IMF provided for a decrease in GDP to -7% for the current year. However, the year ended with an increase of +5%. The error amounted to more than 12 points of GDP – a gap that is infrequent and unexpected for the estimates of well-known professionals. But it must be emphasized that this mistake occurred at a time when relations between the IMF and the Russian government, headed by Yevgeny Primakov, were bad, and the probable causes of the mistake must be sought in a misunderstanding34 of the mechanisms of the Russian economy.

Sapir, like other serious experts, points to the lack of an effective investment policy as the reason for the crisis state of the Russian economy. He notes the illusory hopes of some members of the Russian government for foreign direct investment and, in contrast to this, points to the importance of intensifying investment in the private sector. “Resources derived from both domestic trade and exports,” Sapir writes, “have been only partially reinvested.” At the same time, he states that from 1994 until the financial crisis of 1998, Russian oligarchs “played big.” They “actively used their financial resources to facilitate the re-election of Boris Yeltsin, and then played the card of devaluation of the ruble on the export of raw materials, when world prices fell as a result of the Asian crisis.”35

Balancing Ideals and Results

Comprehending the results and the course of transformations in Russia, analyzing the experts’ assessments, we must conclude that the percentage of negative phenomena in the overall balance of the results of transformations was exorbitantly high. Russia as a state has lost almost a quarter of its territory with the richest mineral reserves, half of its population and half of its economy, assets worth more than $500 billion have been exported abroad, and our military-strategic potential has been reduced by dozens of times.

The main destructive influence stemmed from two circumstances. First, it was the wrong choice of the conceptual basis of economic reforms and turning it almost into a religion. Secondly, from the inability (unreadiness) of society to resist the egoistic pressure of the criminals, who were increasingly merging with the authorities. Moreover, these circumstances taken together were well used by external forces interested in weakening the former political rival.

As is well known, our “elite” did not hesitate to choose certain refined principles of the free market as a conceptual basis for economic reforms, reduced to the form of universal recommendations of the “experienced” West for “newcomers” entering the market world. But more and more well-known economists of the world are forming an opinion that the standard reform policy, recommended at a certain stage by international economic and financial institutions as a model for developing countries and countries with economies in transition, in fact turned out to be quite ineffective and clearly does not correspond to the realities and requirements of the future. This type of economic policy is associated with a set of provisions developed in the early 1990s, called the Washington Consensus, and it remains the basis for existing Russian economic programs.

In fact, sharp criticism of the concept of the “Washington Consensus” now comes even from the circles directly involved in its development. The already mentioned Professor Stiglitz, who until recently served as senior vice president and chief economist at the World Bank, argues that the attractive simplicity of this scientific doctrine is in fact “using a very simplistic model of calculation.” He notes that these programs do not include effective financial regulation, measures to stimulate technology transfer, maintain competition and enhance the transparency of markets.

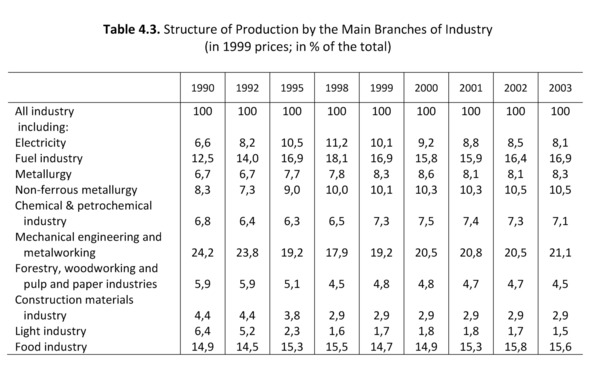

For example, as can be seen from Table 4.3, the structure of industrial production in Russia over the years of market transformations has undergone a clearly negative shift towards a decrease in the role of mechanical engineering and metalworking and a noticeable increase in the share of the fuel industry, metallurgy, chemistry and petrochemistry. Some progress has been made in the development of the food industry, but it is taking place based on the expansion of foreign capital and is often several steps behind the world’s highest technological level. A clear degradation is observed in the light industry sector.

The most tragic consequence of the mistakes of the economic course since the beginning of the reforms is the consolidation of the trend towards the degradation of the productive forces of our country, the transition to economic dynamics based on the consumer attitude to the resource potential of the nation. Clear evidence of this is the strengthening of the raw material orientation of the economy and the sharp curtailment of the manufacturing sector and high-tech industries, the outflow of capital from the country many times higher than foreign investment, the degradation and squandering of scientific potential, the brain drain and, in general, the best genetic fund abroad, a sharp weakening of control over the environment for the sake of current economic interests, etc.

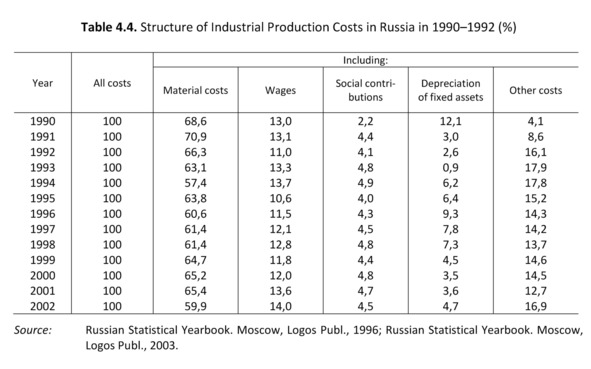

As a justification for the absence of any active innovation and industrial policy with the start of economic transformations, interested politicians and experts usually refer to the lack of investment resources. But this reason is secondary. The main thing lies in the unsatisfactory structure of motivations at enterprises, in the orientation of the behavior of management in economic structures and employees of the relevant state bodies. Table 4.4 shows that there was a serious decrease in 1990—1993 in the share and volume of depreciation deductions, which, as is known, is the most important source of investment in fixed assets. The table also shows how little economic influence the item of labor costs has on the interests of entrepreneurs and workers in the real sector. If the share of labor costs in total costs is 11—13%, and 2/3 of the total costs are material factors, then the creative components of motivations, which are concentrated in the labor potential of enterprises, objectively cannot be properly developed.

The situation in many branches of industry, which in Soviet times reached indicators comparable to the best world ones in terms of technological level and scientific intensity, is very sad. Here is just one of the testimonies (published in 2002) concerning the domestic aviation industry. “Russian aviation has been in a severe crisis for more than a decade. To understand the depth of this crisis, suffice it to say that until 1991 we produced more than 80 long-haul aircraft per year, and in the last five to seven years – two or three, production has decreased by thirty to forty times. And if in 1990 the USSR controlled more than 25% of the civil aviation equipment market, i.e. every fourth aircraft in the world was produced in our country, then since the mid-1990s our share is practically zero. For many years now, the world’s largest aircraft manufacturers have not only not taken us into account, but simply not mentioned us in their marketing studies.”36

The Russian market economy, which did not yet have training in complex market bindings, easily succumbed to new attractive trends in the global financial and economic space, including those related to the separation of financial turnover into an independent business sector, isolated from the real economy, where the dynamism and profitability of operations seemed to be the highest. Under the influence of this circumstance, the formation and development of banks, one of the decisive components of a normal market economy, in Russia, the path of participation in speculative operations rather than the provision of investment and other services to the real sector has taken the path of participation in speculative operations. Most of them limited themselves to performing the functions of financial offices. Overall, the Russian financial system (as well as the finances of many other countries) has become subordinate to the external monetary and financial system based on the US dollar. In the domestic circulation of several countries, the dollar has not just captured individual bridgeheads, but has gained strategic dominance. In Russia, on the eve of 1998, the dollar supply accounted for about 68% of the national monetary base37.

In his introduction to the publication of an expert report on the problems of building the institutional foundations of the market economy, the President of the World Bank, James D. Wolfensohn, has shown that countries with market transformation programs need to be creative, namely to “choose only those institutions that work and reject those that do not.” Countries, he continues, “must have the resolve to do so to abandon unsuccessful experiments in a timely manner.”38

As already noted, one of the main reasons for the insufficient effectiveness of market reforms is the poor understanding by most of the people of the ultimate goals of the reforms, and this stems from the lack of a publicly presented and consistent strategy for the country’s socio-economic development in the long term. During the reform period, the Russian government did not make the necessary efforts to create and maintain a feedback mechanism between the announced programs, their effectiveness in implementation and the perception of transformations by the people. At the same time, it is only with such feedback that it is possible to adjust the content of policies and reforms in a timely and accurate manner, while maintaining the interest of the entire society in them.

Although this principle of regulating influences on social processes has long been known from the theory of governance, in the Russian political elite such productions began to appear too late, and even then, mainly on the part of the opposition. For example, in January 2003, a group of State Duma deputies addressed the President of Russia with the following statement: “In our opinion, the main drawback of all legislative activity is that that bills are proposed for consideration by the State Duma, which, in the opinion of the government, build only a scheme of market relations, but there are no bills aimed at the active participation of the entire population of the country in these relations.”39

Analyzing Reform to Influence Future Policies

The above set of assessments of the period of economic transformations in Russia after 1991 to the present day, in which critical motives predominate, should not be perceived by the reader as a denial of the very need for serious economic and political transformations in the country using all the advantages and opportunities of market relations and the entrepreneurial factor. By focusing on mistakes and miscalculations, we only overcome their silence (often unselfish) and would like to to promote the establishment of the practice of managing reforms according to their socio-economic results, extending to society (people) as a whole.

The management of reforms and transformations according to the criterion of achieved socio-economic results should help to overcome the influence of ideological extremes on economic policy. The deification of the ideals of Western-style market liberalism with boundless self-flagellation of the Russian past, and pride in the spirit of belief in one’s own uniqueness or in the immensity of Russia’s resources can also be dangerous.

We need to accustom ourselves to listening to such assessments, even if not very pleasant, but close to the truth, such as the one that Eric Brunat, European Executive Director of the Russian-European Center for Economic Policy, and Vice President of the University of Savoie (France), made in 2002. “Despite its potential, Russia,” he argues, “is still a country with low labor productivity and high transaction costs.”40 These are indeed fundamental problems for the transformation of the Russian economy, and it is impossible to solve them without addressing the study of all human experience and trends in the world economy.

It is impossible not to agree with the following statement of Academician Oleg T. Bogomolov: “The economy cannot be healthy and efficient if consumer prices, the cost of purchasing housing is steadily approaching and even compared with the level of Western countries, and wages, due to the standards set by the state and the monopoly position of employers, sometimes lag behind by dozens of times. As in the former Soviet Union, the wages of most workers in Russia remain unacceptably low, not only in comparison with other countries with a comparable level of development, but also in relation to the achieved labor productivity. In terms of labor productivity, Russia lags the United States by the factor of 5—6, and in terms of average wages by the factor of 15—20.”41