Полная версия

Trajectories of Economic Transformations. Lessons from 2004 for 2024 and Beyond

China has experienced and is experiencing a real boom in foreign investment, which actively contributes to maintaining consistently high rates of socio-economic development of the country. For example, in 2003 (despite the destructive impact of the SARS factor) foreign direct investment in this country amounted to $53.5 billion, in 2004 – about $60 billion, and in 2010 it is expected to reach $100 billion. per year. And in total, over the years of moving towards a market economy, China has received (including from the Chinese from abroad) probably at least $0.5 trillion in foreign investment.

Thus, the external factors of economic transformations have a multifaceted potential that contains not only negative, but also positive aspects. Therefore, it is unreasonable (because of the dangers of negative external influences or for other reasons) to refuse to take an active part in world economic relations. The advantages objectively present in the international division of labor can and should be used as much as possible during transformations. A country that excluded itself from the global world economy would find itself outside the modern flow of innovation and managerial experience. But in everything, as has long been established, a measure is needed. Reducing the impact of the negative external factors of transformation and strengthening the manifestations of their positive aspects is an objectively necessary and quite feasible task for the governments of countries with economies in transition, even in the increasingly rigid grip of unipolar globalization. The realization of such opportunities depends on the specific policy in the country and the social and moral health of society.

Chapter 3. The Economic Structure of the Soviet Union: From Growth to Collapse

The complex problems faced by the former Soviet Union and Russia and other countries that emerged after its collapse, as well as the difficult course of reforms in them, have formed in a significant part of society a purely negative attitude towards the entire period of Soviet history, including the economic results associated with the 70-year period of socialism. Meanwhile, the USSR, even as of 1985—1986, when the Gorbachev perestroika began, the harbinger of market reforms, it had an economic potential that could not be ignored in the world. This was ensured by the high growth rates of production in the main sectors of the national economy over the previous years. The economy on the territory of the USSR functioned as a single (without exaggeration) national economic complex, all parts of which were located in the space of cooperation branched to detail and were subject to a common plan. For all its serious drawbacks, this cooperation has been quite powerful in binding the country’s economic structures together in a focus on sustainable economic growth. In the external dimension, the country’s economy was presented both objectively and subjectively as a significant factor.

The Nature of Soviet Economic Growth

In 1985, the national income in the USSR reached 66% (according to official Soviet statistics) of the level of the United States. Industrial output accounted for more than 80% and agriculture for 85% of the U.S. figures. The volume of annual capital investments was characterized as 90% of the level of the United States. The comparison in terms of the parameters of economic efficiency looked somewhat worse. For several years, according to the USSR Central Statistical Office, labor productivity in industry was at the level of 55% and in agriculture, about 20% of the U.S.17

Consistently high rates of economic growth distinguished the Soviet economy from the economies of many other countries both in the pre-war (before 1941) and post-war periods. The national income produced in 1940 was 5.1 times higher than in 1928, and between 1950 and 1985 it increased 10.2 times.

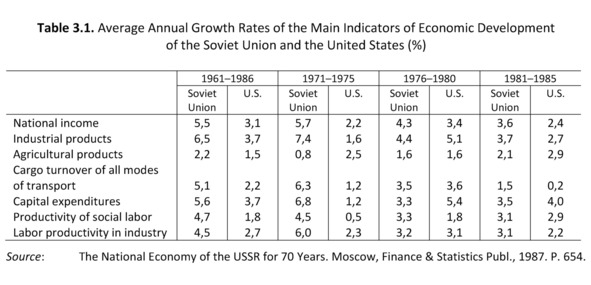

As can be seen from Table 3.1, the USSR was basically ahead of the United States in terms of the average annual growth rates of national income, industrial and agricultural production, capital investment, and some other indicators. At the same time, in the context of the five-year periods presented in the table for the USSR, there is a noticeable tendency to reduce the growth rates of almost all economic indicators.

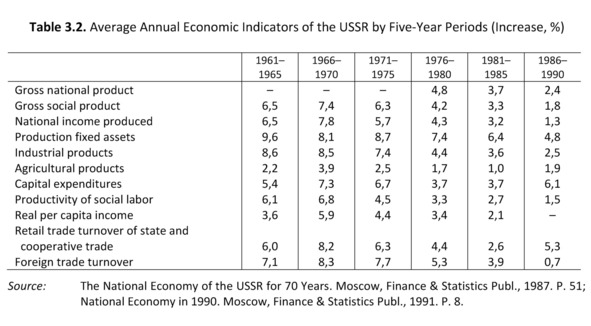

It can be stated that up to the Ninth (1971—1975) Five-Year Plan in the USSR, the average rate of economic growth was quite high, at the level of not less than 6—8% per year (Table 3.2).

This was facilitated by the high scale and rate of capital investment in the national economy and a significant and stable increase in the production apparatus over a long period of time. The growth rate of production in industry was higher than the average in the national economy. Although the productivity of social labor increased continuously, economic growth was extensive rather than intensive. The growth of the well-being of the country’s population clearly lagged behind the rate of economic growth.

Symptoms and Causes of Economic Stagnation

Since the 1970s, there has been a clear downward trend in the growth rate of such indicators as real per capita incomes and retail turnover of state and cooperative trade. During the Twelfth Five-Year Plan (1986—1990), for the first time in many years, the country faced a decline not only in the rate but also in the level of well-being of the people. This was so shocking that in 1986—1990 the government, glossing over this fact, removed the indicator of “real incomes of the population” from official statistics. It was replaced by the indicator of “cash incomes of the population”, which looked more decent due to the invisible presence of incipient inflation in it.

The deterioration of the overall economic dynamics affected the weakening of the country’s position in foreign trade. The average annual growth rate of foreign trade turnover fell from 8.3% in 1966—1970 to 0.7% in 1986—1990.

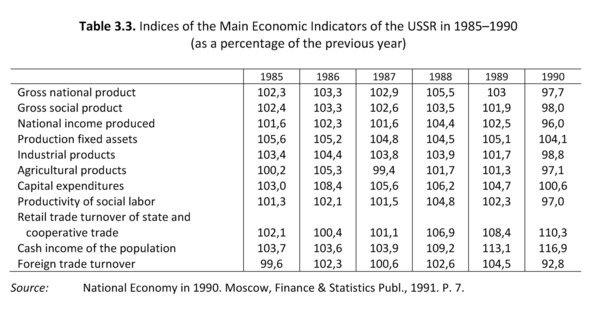

The dynamics of economic parameters in the USSR in 1985—1990 is indicative (Table 3.3).

From a comparison of the data for 1985, it is not difficult to conclude that it was a clear reflection of economic stagnation. This underscored the urgent need for major changes in the economy and society. The figures for 1986 and partly for 1987 testify to attempts to implement these changes proclaimed by perestroika and Gorbachev’s policy of “accelerating” socio-economic development. The growth rate of capital investment sharply increased (to 8.4% in 1986).

The growth rate of industry increased slightly, mainly due to investments in mechanical engineering. But then these intentions to accelerate economic development fizzled out. The year 1990 ended with an absolute decline in GNP, industrial and agricultural production, social labor productivity, and foreign trade turnover. In 1988—1990, as if in opposition to this, retail trade turnover and cash incomes of the population began to grow rapidly, which embodied the growing inflationary trends and, at the same time, the exhaustion of the ideas of “perestroika” and “acceleration”, which were replaced by new slogans of the “social orientation” of the economy.

Fundamental Flaws in the Soviet Economic System

It can be argued that the fundamental flaw of the economic system that existed for a long time in the country was its inability to overcome the extensive framework of economic development and to include the factors of economic intensification caused by the radical shifts in world science, technology, and management after the 1950s.

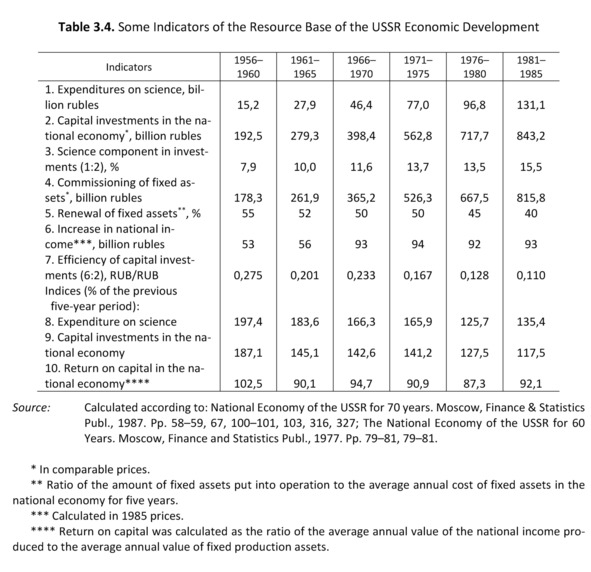

The sphere of science and engineering in the country, especially after the end of the Second World War, was among the most privileged areas of activity. As can be seen from Table 3.4, the growth rates of investments in science were quite high.

In terms of the level of knowledge intensity of the economy, the USSR quickly reached indicators commensurate with the most developed countries of the world. Even on the eve of the collapse of the USSR in 1990, expenditures on science from the state budget and other sources amounted to 5% of the country’s national income.

The total expenditures on science from the state budget and other sources for the period 1986—1990 in the USSR amounted to 153.3 billion rubles, i.e., their growth compared to the previous five-year period (1981—1985) amounted to 116.9%.

It is impossible not to admit that the initial period of the reversal in the world of the scientific and technological revolution was also full of events in our country that inspired great faith in its capabilities. In the USSR, there was a rapid increase in investment in the field of science. If in 1950 expenditures on science in our country amounted to 1 billion rubles, or less than 1.4% of the national income, then in 1960 it was 3.9 billion rubles (2.7%), in 1970 it was 11.7 billion rubles (4.0%). In the 1970s, the USSR was on par with the United States in terms of the relative value of spending on science to national income. Over the past 20 years (from 1950 to 1970), the number of scientific workers in the Soviet Union has increased by 5.7 times, and their share in the total number of workers and employees in the national economy has increased from 0.4% to more than 1%.

The significant absolute and relative increase in resource investment in science, especially in the 1960s, did not, however, lead to an adequate increase in its contribution to the national economy. The transformation of the productive forces based on scientific discoveries and inventions and the proclaimed task of “combining the achievements of scientific and technological development with the advantages of the socialist economic system” proved to be a much more complicated matter in practice than it was seen in theoretical reflections on the future of scientific and technological revolution. There was a lack of perseverance and dedication to ensure the effective materialization of R&D achievements at the level of state programs, and due attention was not paid to the reorientation of investment policy to the process of accelerating scientific and technological progress. Although during each five-year plan the fixed assets in the national economy were on average renewed by about half (see Table 3.4), the involvement of means of labor of a fundamentally new scientific and technical level in the economy did not occur on the required scale. As a result, from one five-year plan to another (except for the Eighth Five-Year Plan, 1966—1970), there was a decrease in the efficiency of capital investments in the national economy. The increase in the national income produced per ruble of capital investment in the Eleventh Five-Year Plan (1981—1985) amounted to 11 kopecks, which is 2.1 times lower than in the Eighth Five-Year Plan, and 2.5 times lower than in the Sixth Five-Year Plan (1956—1960). Was it possible to reverse this trend at that time? In principle, yes, if it were possible to organically combine the investment process with scientific and technological progress, to turn capital investments into a reliable guide to the national economy of the most effective achievements of science and technology18.

These assessments were made in the political conditions of the pre-reform period. They are rather harsh in their criticality, but inevitably still bear the imprint of faith in the country’s ability to correct the flaws of the system within the framework of evolutionary targeted reforms.

Missed Opportunities and Unrealized Approaches

Comprehending today, considering the time that has passed, what I, as a researcher, wrote in the pre-transformational period, I must be more critical of myself. Yes, at that time, many of my ideas about our economy and society, as well as those of a few other scientists, were formed under the influence of a priori belief in certain ideals. In addition, many of the deep-seated flaws of the socio-economic system were not fully revealed to researchers at that time due to insufficient access to information. It seemed that most of the shortcomings of economic management in the country depended on subjective causes and could be eliminated with proper adjustment of the policy of the authorities. There was a hope for the existence and operation of national (nationwide) economic interests as the main factor in motivating people’s behavior.

In many of my developments, I and some other economists proceeded from the possibility, through rational transformations of economic structures and forms of economic management, of building such a system of economic interests of enterprises and associations that would correspond to the structure of the long-term needs of society. In our opinion, this should ensure a stable interest of economic entities in the best (most effective) satisfaction of the needs of society and, accordingly, generate and reproduce the economic responsibility of these subjects for the degree of satisfaction of the needs of society.

All this presupposed a high degree of democracy in society, transparency of entrepreneurial aspirations and actions of the authorities, and broad opportunities for public control. At the same time, the mechanism of market competition (competitiveness) in the behavior of economic entities oriented towards satisfying the needs of society was thought to be organically immanent in the entire system of economic relations.

From these prerequisites, the proposed solutions to ensure socially promising (strategic) approaches to the reproduction of the technological base of the economy, the creation of conditions for achieving the greatest growth in the final efficiency of the economy in the process of renewal of the production apparatus followed19. The implementation of such approaches was focused on the mechanisms of optimal economic distribution of resources according to aggregate development goals within the framework of economic units specializing in meeting the basic needs of society. For this purpose, it was proposed to use detailed new methods of block-modular renewal of the production apparatus, which assumed an organic connection between investments in the economy and the implementation of the most effective scientific and technological innovations20.

All these, as well as many other tempting offers, were not realized, for which there are many reasons. First, it is necessary to admit that in the development of the proposals, hopes were unjustifiably high for the possibility of understanding at the level of the central economic management bodies the key interrelations of the optimal development of the country’s economy, which is tuned to meet the needs of society. Here we must admit the truth of Friedrich von Hayek’s accusation against economists who believed (as we did then) in the possibility of a planned socialist economy, when he observed that “socialists, victims of arrogance, want to know more than is possible.”

Secondly, the policy of our state at that time was fundamentally lacking purpose and energy. Collectivist-socialist driving forces were no longer brought into action by this state policy, as had been the case at certain stages earlier. And competitive entrepreneurial driving forces were not given the opportunity to emerge and express themselves. Ideological frameworks and regulatory frameworks severely limited and suppressed entrepreneurial initiatives.

There was a great inertia of the approaches that assumed the eternal priority of the development of the “first subdivision” of social production (the branches producing the means of production) over the “second subdivision” (the production of consumer goods and services). Ideas about the expediency of building chains of expanded reproduction based on the structure and dynamics of people’s ultimate needs were rejected from the outset. Consequently, the technical level and the scientific equipment of the industries directly working to improve the well-being of the people fundamentally lagged behind the branches serving the production of means of production. For example, in 1987, the ratio of R&D expenditures to manufactured marketable products in the USSR Ministry of Light Industry was less than 0.09% compared to 2.9% on average in the country’s machine-building complex.

In general, as of the end of the 1980s, the level of knowledge intensity in the main branches of material production in our country was noticeably lower than in the most developed countries of the world. According to available estimates, the average ratio of science intensity in the USSR and the USA was about 1 to 2 in civil engineering, 1 to 3 in chemical and metallurgical industries, and 1 to 5 in electric power industry. Although expenditures on science in the USSR and the United States were considered close as a share of national income (in 1987 they were 5.2 and 5.8 percent, respectively), the absolute amount of spending on science in the USSR was much less than in the United States. In 1987 they amounted to 32.8 billion rubles against $123.6 billion (1986) in the United States.

The Soviet Union of the 1980s and 1990s was exhausted by competition (complex competition) with a much more powerful rival in the face of the United States (plus the countries of Western Europe, Japan, etc.). Maintaining military parity with the West required concentrating most intellectual and economic resources on the development of the defense complex. The volume of defense R&D in the USSR was estimated to be 3:221 on average. Moreover, the defense research sector was characterized by large overhead costs, which absorbed a considerable part of the appropriations for science and innovation. It turned out that the scientific support of that sphere of the country’s economy, which, under the normal structure of the economy, in fact, should be the main space of the economic process of expanded reproduction, was prohibitively low.

Perestroika: Ideas vs. Realities

The period of 1985—1990 was a very difficult and contradictory time for the country’s economy. In a political sense, it set the pace for the turbulent changes that were overdue. The beginning of perestroika was tinged with the euphoria of the emancipation of society, and therefore the strategy of “accelerating the socio-economic development of the country” looked like a completely natural direction for that time. The course taken for the rise of machine-building, the acceleration of scientific and technological development and structural shifts aimed at intensifying production was logical in concept and, moreover, relied on the historical confidence of the ruling party, which was accustomed to achieving its goals. But, faced with the very first difficulties and contradictions of the turn from an extensive to an intensive type of management, which presupposes a qualitatively different level of economic mechanism and management, the country’s leadership began to glide on the path of improvised gliding on the surface, moving away from solving real problems towards populist tasks that are in full view of the media.

Inconsistency and superficiality in the formulation of the main goals of state policy had a particularly destructive effect. As early as 1986, almost immediately after the announced decisions to “accelerate scientific and technological progress” and the short-lived propaganda of this direction, another slogan appeared, focusing on “overcoming technocratic approaches” in socio-economic policy. Moreover, it was presented in such a way that it disavowed the value of the task of deploying technological progress and the transition to qualitatively new technologies. At the same time, the idea of a “social reorientation of the economy” and its subordination to the “human factor” began to be intensively promoted. This formulation, which was justified in principle and even belated in many respects, was then taken to a primitive extreme, which blurred the previously initiated actions to reorient investment policy in the direction of technological progress.

An insidious role was played by the idea of regional self-financing, which gained special favor in the Soviet Baltic republics. It was used to show the supposedly significant driving forces of economic development that are revealed in the event of the separation of regions (republics) from the center that binds them into an independent circuit. To this end, the launched information about “injustices” in the macroeconomic exchange between the Russian Federation and the Baltic republics was actively circulated. The problem of “exploitation by the Russian Federation” was especially persistently raised in some circles in Estonia. None of the official statistics based on input-output balances, which testify to other (contrary to the emotional conclusions of local politicians) ratios of imports and exports between Russia and Estonia (other republics) were considered. Such sentiments have spread in a few other Union and autonomous republics. They contributed in no small measure to the collapse of the USSR as an integral state and as an economic complex.

Significant and far-reaching damage was caused by the ill-conceived advancement of the tasks of a universal turn in politics to “universal values.” This turn, seemingly logical in its essence, was again brought to the point of absurdity and eventually turned our own fundamental goals into tasks secondary to certain global values inherent in an abstract “civilized” community.

Many researchers, including the author of these lines, wrote about the mistakes and dangers of such a course at the time, but this was not perceived by the political elite. As an example, let us cite our statements on the situation and economic policy in the country, published in June 1991.

Based on the analysis of the dynamics of the main socio-economic indicators, we then tried to identify the “stage” causes that led to the escalation of the crisis in the economy. One of these reasons is related to the structurally unadjusted investment boom of 1986, when there was a sharp increase in capital investment in the national economy as a whole and in industrial facilities, especially in mechanical engineering. This boom turned out to be purely extensive, even though a policy was proclaimed for the use of qualitative factors of growth and for the effective acceleration of scientific and technological progress. Such a significant drawback of investment policy was later supplemented by the disproportion caused by an ill-conceived anti-alcohol campaign, as well as populist interpretations of the policy of social reorientation of the national economy and “overcoming technocratic approaches” in the economy. This, on the one hand, served to further deaden production investments in the unfinished construction of facilities of the technological level the day before yesterday, and on the other hand, prepared the conditions for a serious imbalance of supply and demand in the consumer market due to a sharp decline in the receipt of consumer goods (-10 billion rubles), accompanied by an increase (uncovered by resources) of cash income in the investment sector.

Another concentration of imbalances was 1988, when the growth of monetary incomes of the population increased by 2.5 times, and the output of consumer goods by 6.4%, but if we do not consider alcoholic beverages, then only by 5%. The state budget deficit reached a record level (81 billion rubles), having increased by 5.8 times compared to 1985. In 1988, there were high absolute increases in GNP (50 billion rubles against 26 billion rubles in 1987) and produced national income (31 against 12 billion). But there were no adequate increases in the physical quantities of the product behind this.

The dynamics of production in physical terms for the most important items of the nomenclature of industrial products considered in monthly reporting (158 items) is characteristic. If in 1986 there was a steady growth, and in 1987 a decrease in output affected a part of the products, mainly mechanical engineering, then in 1988 there was a decline in the production of every fifth type of product, and in 1989 – almost half of its most important types. The year 1988 was a springboard of inflation and economic anarchism, which was caused by unsuccessful laws on enterprise and cooperation, and the ill-considered breakdown of the old state structures. A huge destructive impact was exerted by the rapid removal of the previously existing distinction between cash and non-cash money turnover. All this has created space for the egoistic aspirations of the leaders of enterprises and cooperatives, the speculative elements, who are the most dexterous in redistributive actions.