Полная версия

Trajectories of Economic Transformations. Lessons from 2004 for 2024 and Beyond

“Radical innovations are the main lever for the transformation of society,” say Boris N. Kuzyk and Yuri V. Yakovets in a recently published multifaceted book on the problems of Russia’s long-term strategy9.

All experience shows that our country developed most dynamically when integration tendencies were strong on its vast territory and creativity in human activity was encouraged. Therefore, science and scientists have traditionally been in a high place in our society. And today, despite the colossal losses in scientific and technical potential in Russia during the first years of reforms, there are still all the prerequisites for the development of the economy along a science-intensive path. For example, in terms of the number of scientists and engineers in the field of R&D per million inhabitants, Russia is on a par with the United States and is ahead of Germany, France and the United Kingdom, not to mention a huge gap with Poland, China, and India.

Development, based on the priority of innovative approaches, is the main way for Russia’s self-assertion in the world, which is necessary today. But it is also a way of correcting dead-end branches of development, into which, under the influence of the trends of the past, significant parts of human society are ready to stray.

Thus, much will depend on how the transformation processes initiated in the post-socialist countries develop further. This is important not only for the large number of people living in their territories. The experience of these transformations should also clarify the attitude towards the trajectories of changes in the economic systems of the global world. The events of 9/11 gave an impressive signal that history will not be able to follow the traditional milestones that are derived from the evolutionary prolongation of the economic paths of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Chapter 2. Internal and External Drivers of Transformations in Russia

The transformation processes that unfolded in the second half of the 1980s in the USSR and in the countries of the Soviet bloc are considered and comprehended in the literature in their various manifestations and in various contexts. Great interest was aroused by critical and at the same time constructive reviews of trends in the Soviet and post-Soviet economies in large monographs, which were prepared by prominent Russian economists whose authority was established in Soviet times and who continued to lead an active research life in the new conditions10. Valuable information is drawn from works containing a view of the transformation processes in Russia on the part of well-known and experienced foreign scientists11.

Does the existence of such authoritative sources mean that there is no need to stir up the past? Of course not. The longer the path traveled, the higher the price of appeals to various events that become the property of history, if they are covered by witnesses of time. The process of “cleansing” events of layers caused by political biases and limited information is very complicated. After all, the interpretation of the essence of events is always subjective and strongly depends on the needs of the moment of analysis. One of the most difficult issues in this case is the arrangement of representations made from diametrically different points of observation: representations based on comprehension of the internal logic of events, and representations containing the logic of the external contour of transformation processes.

Two Key Drivers of Economic Transformations

The transformations in Russia and other post-socialist countries have been caused, as already noted, for a variety of reasons. However, in my opinion, the analysis somewhat underestimates the division of the causes and factors of transformations into two large groups, related, on the one hand, to internal (intra-country) circumstances and contradictions, and, on the other hand, to the conditions and factors of an external order.

The internal reasons that necessitated the transformation of Russia’s economic system were determined by the accumulated contradictions in the country itself, contradictions that began to hinder the development of productive forces on an intensive basis and clearly limited the growth of the nation’s well-being in accordance with new conditions and socially justified criteria.

Here it is necessary to emphasize the socio-economic factors and contradictions that have developed in connection with the stable isolationism of the development of the country (Soviet Union) in relation to the world community. This state hindered the free exchange of ideas, seriously impoverished the motivation of citizens and business entities, excluding long-term entrepreneurial interest from it, and ideologized the criteria for economic development. The lack of competition, the tendency to stagnate, the costly nature of the economy, the dominance of extensive reference points of reproduction, the inhibition of incentives (motivations) for scientific and technological innovations, the substitution of real business in the economy with the imitation of results adjusted to the reporting and planned indicators, the cumbersomeness of the system of administrative and ideological management, and others – all this generated and strung together numerous contradictions that needed to be resolved radical changes in the system.

The external causes of economic transformations, in turn, can be divided into two large groups.

In the first group, we include those drivers of change that are determined by a country’s competitive position relative to the economies of other countries in the world. The comparison of trends in the external (seemingly prosperous) world with stagnant trends within the country was a significant source of motivation for changes in the economic system. Such aspirations in Soviet society became especially strong after the removal of political barriers to various contacts with the outside world, including mass tourism and official trips of our citizens to capitalist countries. In the practice of subsequent reforms, however, these motivations were reduced to imitations of the outside world and meant mainly the desire to adapt to it, and to a lesser extent the desire to compete with dynamic countries.

The second group of external driving forces of institutional transformations consists of the special economic and political interests of other (primarily highly developed) countries and transnational economic entities in relation to Russia and entities on its territory. In our society, they did not timely assess the existence of such external interests that oppose national interests and failed to neutralize their negative impact on their development, at least by clear statements about their strategic intentions, not to mention clearer actions in practical policy in accordance with the strategy put forward.

Setting Criteria for Economic Reform

The internal need to ensure a more efficient management and transfer the economy to a comprehensively intensive, innovative type of development has in fact been and remains the main impetus for the transformation of the economic and socio-political system of Russia. Therefore, it is quite justified to continue to focus on domestic problems during reforms, on overcoming the negative legacy of the stagnant past, and on the formation of a new level of institutional base. The fundamental question on which the attitude of society to the ongoing reforms depends in this approach is the question of the compliance of the reform actions with the basic criterion that would meet the long-term interests of the country as an integral community of people.

This basic criterion is extremely difficult to quantify unambiguously in one or more indicators. In addition, in dynamic terms, it changes from period to period, is supplemented with new parameters or, on the contrary, is characterized by a decrease in the weight of some controllable quantities. But that doesn’t mean it’s elusive or completely subjective. The criterion of socio-economic progress is inevitably felt and controlled by society. as well as its individual individuals, regardless of what analytical summaries the official authorities prefer to publish and control. In the final analysis, this criterion is always based on society’s assessment of the dynamics of the country’s productive forces as a factor and condition for a stable positive change in the level of the nation’s well-being.

If this conclusion is recognized as valid and fundamental for the formation of the country’s strategic policy, then a sufficiently stable, clear, and consistent methodological basis for analysis in unity of goals, factors and conditions for effective socio-economic development, for a correct understanding of the driving forces and tasks of economic transformations appears.

With the passage of time since the start of reforms in Russia, it has become more obvious that when choosing the ways of transformation, the elite of our society has not been able to show independence and has succumbed to assessments that do not quite correspond to an objective approach.

First, the state of the economy and society was overly dramatized. In fact, at the time of the start of the reforms, Russia was far from being in the last echelon of the world economy, although it lagged the United States, Germany, and similar countries in most of the parameters accepted in the traditional analysis. As of 1987, Russia’s GDP per capita (in purchasing power parity prices) was 30.9% relative to that of the United States, while similar figures were in South Africa (22.4%), Brazil (24.2%), Turkey (20.4%), South Korea (27.3%), Malaysia (22.9%), and Egypt (14.3%). And in the lowest echelon – the low-income countries, in the terminology of the World Bank (for example, in Ethiopia, Mozambique, Tanzania, Chad) – per capita GDP relative to the United States was only about 3%. In other words, Russia did not need to be tempted to start from scratch.

Secondly, the emphasis was not placed on the most important problems that determined the unsatisfactory trends in the USSR (Russia) in the pre-reform period. The focus was on the problems of the economy in the narrow sense of the word and on the transformation of the institutional framework, while the fundamental contradictions rested on the shortcomings of human resources, the educational system, and the anti-innovation nature of management. As of 1980, the share of education expenditure in GDP in Russia was only 3.5%, while the world average was 3.9%, in the United States 6.7%, in Sweden 9%, in Japan 5.8%, and in the United Kingdom 5.6%.

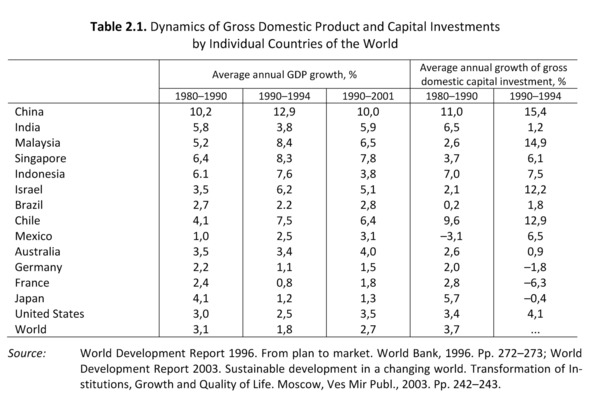

Third, the chosen external “models” based on which the national reform program was formed turned out to be unjustifiably one-sided. The experience of the “non-Western” countries, such as China, India, Malaysia, etc., was ignored. Meanwhile, in terms of objective parameters, there have already been many “neutral” countries that have developed more dynamically (Table 2.1) and are more balanced in the structural sense than, say, the leading countries of the G7.

Many of these countries have not become passive actors in globalization processes. They did not allow themselves to be strayed into the style of complaining about the behavior of the “sharks of globalization”, and by all their routine steps in economic policy they tried to join the slightest progressive consequences of this for themselves. For example, China, according to some experts, is undoubtedly implementing the outcomes of globalization with undoubted benefits for itself (despite some costs)12. As a matter of fact, Japan also made its famous breakthroughs during the post-war modernization of the economy due to the rapid absorption of the achievements of external global development, especially in the field of scientific and technological development, management technologies, and so on.

A Romance with External Aid

Today, it is clear to an increasing number of observers that over the past period of market transformations, Russia has not so much gained as lost its economic potential (we will dwell on these pros and cons in more detail below). The losses incurred were largely due to the inability of analysts and political leaders of those times to understand the correlation between internal and external incentives for the process of transformation of the economic system and the lack of will on the part of society to demand an account from the elected leadership for the actual, corresponding to the above criterion (and not imaginary) effectiveness of the transformations carried out.

In some cases, the external factors of transformation in Russia have played a rather insidious role. This is especially true of the group of factors that was conditioned by the special economic and political interests of highly developed countries and their large economic entities, which were laid down (sometimes explicitly, but more often covertly) in various kinds of recommendations regarding reforms to Russia, in the loans granted, in foreign economic transactions, and so on.

At the same time, I would like to unequivocally note that the negativity resulting from this circumstance in the form of losses and ineffective outcomes for Russia cannot be presented as an accusation against our foreign partners. These partners deserve respect as truly sensible economic and political actors who pursue their policies and persistently build them in accordance with their own economic interests. It would be strange for a country (or a firm) that has long lived under capitalist competition if it cared more about Russia’s interests or its own “universal values” than about its own interests in the course of its behavior.

Accusations should be brought against us, for all citizens of the country for the frivolity inherent in the advanced elite, for the lack of qualifications and experience of our leaders and businessmen, for tolerance in society towards those who managed to take advantage of the confusion to organize “trade” in the interests of the nation for their own selfish purposes. If society was to accept the realities of market relations, it should have demanded that the elite and the government develop immunity from the behavior of Russia and its representatives in external relations as a weak, dependent partner. The market has never nurtured the weak, it must, by definition, subordinate them to the strong or destroy them altogether.

The long period of peaceful coexistence of countries with different political systems and levels of development and the absence of major conflicts have led to illusions about the harmony of their relations. Therefore, at the start of market reforms in Russia, many people had the idea that, for example, the West was asleep and saw the longed-for future, when Russia, after the completion of the transformation of socialism into capitalism, would join a friendly alliance of highly developed countries as a more powerful force than before. For some reason, it did not occur to the relevant conceptualists that this idea was, to put it mildly, illogical, inconsistent with the normal psychology of capitalist competition.

Over the years of peaceful coexistence and subsequent globalization, the competitive principles of economic and political relations in the world have not weakened but have become more strategic. The intensity of competition has increased due to the sharp increase in per capita consumption of energy resources in highly developed and medium-sized countries and the perception that these resources are finite. In addition, there are significant technological opportunities for those with financial and intellectual advantages to influence the positions of competitors by initiating deliberate crises. Such attempts have become almost the norm of behavior of the powerful of this world.

The Western countries had powerful motivations to weaken and liquidate the socialist camp led by the USSR and its economic system. After all, it was the main economic and political competitor at that time. The ideological component helped the West to accomplish this task, since the communist (socialist) system was already presented in the eyes of the mass philistine as the main concentration of “uncivilizedness,” as an “evil empire,” and so on. Subsequently, it became clear to many that the goal of suppressing communism as such was secondary, not the most important. Communism as an ideology was no longer dangerous for the developed West. In fact, the task of suppressing our country, as the main center of economic competition and military rivalry at that time, was of fundamental importance. Another aspect of this orientation of the West’s policy was the prospect of advantageous access to the rich resource base of the USSR.

The fact that one country has benefited the most from this – the United States, which has turned from just the leader of the West into the only superpower in the world – did not immediately become obvious. But with the passage of time, it has become apparent that the world is entering a new era of fierce competition. This was especially evident after several global and local financial crises initiated by transnational corporations, and as the formation of serious centers of opposition to American financial and economic hegemony in Europe and then in Asia. The euro has become an obvious competitor to the U.S. dollar as a world currency. From time to time, the Japanese yen and even a hypothetical Asian currency based on the Chinese yuan indicated themselves in the same capacity.

Thus, today there are enough grounds to isolate the real meaning of the interests of those circles that were the most active conductors of the ideas underlying the Western options for the transformation of the economy in Russia and in other post-socialist countries. The conceptual limitations of these options will be discussed in later sections of the book. At this point, it is necessary to emphasize the conclusion that these external impulses for the transformation of the economic and political system carried a significant share of deliberately destructive components in terms of their impact on Russia’s productive forces and competitiveness.

Shifting Internal Forces Driving Change

The noted impact of the external contour has had a significant impact on the structure of the internal driving forces of the transformation of the economic system in Russia. In the structure of the interests of our society, the interests of small but powerful groups of people have taken an undue place due to economic support from the outside. The real interests of the entire Russian society were largely crushed by the force of special economic interests emanating from the milieu of pseudo-entrepreneurs. which arose on a special soil, which was a mixture of the “Komsomol” and semi-criminal mentality. Moreover, such a specific entrepreneurship began to gain ground in business at a time when effective institutions of normal market relations simply could not yet appear within our country.

The initially formed structure of economic interests strongly influenced the further change of institutions in the country. The vector of these interests was determined by two major components: first, the emergence of the interests of the shadow economy with a criminal orientation of the owners of this capital, and second, the emergence of a layer of enterprising people who quickly got their bearings in the new situation and managed to find themselves on the crest of privatization of the most lucrative parts of the national wealth in the context of the “denationalization” of the economy. Among this last group, there were unions of nomenclature figures of the former system with initiative people from the scientific and creative environment. Some representatives of the former Komsomol apparatus turned out to be especially active in the field of not quite pure privatization.

These structural groups, merged in their mercenary motivations with the interests of external forces to weaken the economic potential of the former Soviet bloc, set the tone for major changes in state and public institutions in Russia and many other countries. Under their decisive influence, the political and economic system of the country was formed, and the new state machine, in turn, began to serve its creators to an increasing extent.

Many researchers who have observed the processes of institutional transformations in Russia have believed that the initial distribution of ownership of capital in the implementation of reforms is important only in the sense that it must correspond to the private capitalist principle and be based on individualistic motivation. The expectation was that, in accordance with Coase’s theorem, after a while all possible injustices of the primitive accumulation of capital would be eliminated by themselves.

Indeed, Coase’s theorem in its original version states the following: “The redistribution of property rights takes place on the basis of a market mechanism and leads to an increase in the value of the products produced,” hence “the final result of the redistribution of property rights does not depend on a legal decision [regarding the original specification of property rights]”13. However, it should be borne in mind that both Ronald Coase himself and his followers and interpreters later made important clarifications about the boundaries of this theorem. It was pointed out that the initial distribution of title deeds was irrelevant from the point of view of efficiency only “under conditions of perfect competition” and “if transaction costs are negligible”.14

That these latter conditions are far removed from reality in the real modern economy probably does not require extensive proof. It should be asserted even more confidently that the assumptions about “zero transaction costs” or the existence of “free competition” did not correspond to the realities of the period of the reversal of market transformations in Russia. The asymmetry of information used in economic decision-making by different agents of the entrepreneurial class was glaring in Russia. Involvement in this information radically depended on the proximity of economic agents to the power structures and on “investments in corruption”. Under these conditions, transaction costs were by no means zero, but commensurate with the volume of the final economic product.

It would also be necessary to assess in a transactional manner the cost components that arise from external efforts to transform institutions in countries with economies in transition. The level of external investment in different countries of this group was different at the initial stages of transformation. The volume of foreign aid was especially large in such countries as Hungary, Poland, the Czech Republic, the Baltic states, which were formerly part of the USSR, – Estonia, Lithuania, Latvia. The selective nature of financial assistance to transforming countries speaks for itself in many ways. For example, net official assistance to Poland from international organizations amounted to $876 million in 1998, $1,186 million in 1999, and $1,396 million in 2000. These are the largest amounts of aid compared to what has been received by other countries in Central Europe and the Baltics. For example, the three Baltic states together received $323 million, $318 million, and $254 million in the corresponding years.15 In this regard, if we talk about the level of official assistance to Russia and such countries that were formerly part of the USSR as Belarus or Moldova, then it is absolutely symbolic against the background of even the volume of assistance provided to the above-mentioned Baltic countries.

In addition to the channels of “official aid,” “foreign investment,” “forgiven” foreign loans, and so on exert a significant and varied external influence on the transformation processes in the post-socialist countries. In Russia, so-called foreign investment had almost no positive impact on the real economy. A significant part of them were various kinds of “systemic” loans, which either patched up the needs of the country’s current budgets, or flowed through complex channels, settling in private funds of incomprehensible social purpose. Many commercial loans were “tied.” In addition, the volume of foreign investment in Russia was not commensurate with the scale of the country, and it was an order of magnitude (or more) lower than, for example, foreign investment in the economy of China or even Poland. Between 1994 and 1998, Russia received $13.6 billion in foreign direct investment, while China received $198 billion. According to some reports, Poland has received about $450 billion from the West in various kinds of investments and assistance during the entire period of market reforms.16 It should be noted that the foreign investments that came to these and many other reforming countries were implemented by their governments (unlike Russia) for the benefit of macroeconomic development.