полная версия

полная версияThe Battle of the Marne

Foch replied from Plancy, at 10.15 a.m.: “The 42nd Division will arrive on the front Linthes–Pleurs. Whatever be the position, more or less in retreat, of the 11th Corps, we count on resuming the offensive with the 42nd Division toward Connantre and Corroy, an offensive in which the 9th Corps will have to take part against the (German) right from Morains to Fère Champènoise. The 42nd Division has been on the way since 8.30, and will be ready to go into action about midday. The 10th Corps has liberated it. The 10th is at our disposition, and has orders to support the Moroccan Division to prevent the enemy penetrating to the west of the Marshes of St. Gond.” On receiving similar instructions, Dubois sent two squadrons of hussars to make a provisional link between the 9th and 11th Corps, and intimated to his divisional commanders not only that they must stand firm, but that, in the classic phrase of Joffre, “no failing will now be tolerated.”

Blind words, only to be justified on the lines of Nogi’s apophthegm: “Victory is to him who can resist for another quarter of an hour.” They were hardly uttered when Mont Août, the north-eastern bastion of Dubois’ line, stubbornly defended for five days, was lost. Much of the artillery of the Prussian Guard had been concentrated on this outlying watch-tower of the Sezanne hills; and, in those early days of the war, nerves were not so steeled that a position heavily bombarded and definitely turned could be long held. Of the two brigades of the 52nd Reserve Division, the 104th had been detached to Moussy’s 17th Division; the 103rd remained under the command of General Battesti. Of the former, the 5th battalion, 320th Regiment, under Commandant Meau (known as an author under the pseudonym “Jean Saint-Yves”) was posted on the north slopes of Mont Août; two companies of the 51st Chasseurs were on the east; and Lt.-Col. (afterwards General) Clandor, with the 6th battalion, was in the wood at the foot of the hill. Meau, with wounded head bound in bloody bandages, “like a Crimean veteran,” as a combatant says, was keeping his men firm under a rain of light and heavy shells commencing at about 9.30 a.m., and Clandor was also determined to hold, when it suddenly became known that the 103rd Brigade, on their right, had received an order to retreat, apparently given by Battesi in alarm at the extent of the enemy’s advance.68 First in twos and threes, then in masses, the reservists left the woods that cover the eastern slopes of the hill, and hurried westward, groups of horsemen galloping past them, and gun-teams plunging through the meadows. The whole line was thus shaken; and, shortly afterward, the two batteries which had hitherto sustained the men on the crest were silenced by German guns that had got round behind Ste. Sophie Farm. At 11.45 a.m., Moussy gave Meau and Clandor orders to fall back; but their obstinacy had its reward—Mont Août was never occupied by the enemy. The debris of Battesti’s brigades were rallied during the early afternoon on the hills of Allemant and Chalmont. A part of Moussy’s Division was driven south, and, after a gallant recoil at Ste. Sophie Farm, drew off to the west.

What had become of Grossetti and the 42nd, the last hope of the French centre? From Soisy to Linthes is a march of only 12 miles, and they were to have started at dawn—had started, Foch said, at 8.30 a.m. Exhaustion, hitches in the replacement by the 51st, and the needs of Mondemont may explain the harrowing delay. Messengers were sent out, without result. Foch, fuming at Plancy, issued note upon note to encourage his lieutenants. “Information shows,” he wrote at noon, “that the German Army, after having marched without rest since the beginning of the campaign, has reached the extreme limit of fatigue. Order no longer exists in their units; regiments are mixed together; the Command is confused. The vigorous offensive of our troops has thrown surprise into the ranks of the enemy, who thought we should not offer any further opposition. It is of the highest importance to profit by these circumstances. In the decisive hour when the honour and safety of the French Fatherland are at stake, officers and soldiers will draw from the energy of our race the strength to stand firm till the moment when the enemy will collapse, worn out. The disorder prevailing among the German troops is a sign of our coming victory; by continuing with all its force the effort begun, our army is certain to stop the march of the enemy and to drive him from our soil. But every one must share the conviction that success will fall to him who can endure longest.”

There were, in fact, disorders in the invading host. All morning, Prussian and Saxon soldiery had been making public revel in Fère Champènoise, breaking open and pillaging houses and shops, drinking, dancing, and singing in the streets. Nevertheless, the fighting columns advanced steadily. At 1 p.m. the Guard reached Nozay and Ste. Sophie Farms and entered Connantre, and the Saxons Gourgancon. Radiguet’s Division of the 11th Corps, after a brave stand at Oeuvy, drifted before them, first to Fresnay, then to Faux and Salon. Foch did not waver in his intentions. “The 42nd Division is marching from Broyes to Pleurs,” he wrote at 1 p.m. “It should face east between Pleurs and Linthes, so as to attack afterward in the direction of the trouée between Oeuvy and Connantre. The attack will be supported on the right by the 11th Corps, on the left by all available elements of the 9th Corps, which will take for their objective the road between Fère Champènoise and Morains.” The meaning of the word trouée as here used must not be mistaken. It presumably meant the highroad to Fère Champènoise. There was no such “gap” between the Prussian and Saxon forces as some writers have imagined; and they were both, at the time of this note, three miles or more south of the line Oeuvy–Connantre.

Though the situation was not so simple as the idea of a “gap” would suggest, Foch had accurately gauged its character and the peculiar weakness of the German advance. It has been noted that this was at first inclined (partly by the lie of the roads) in a south-westerly direction. One result was to relieve the pressure on the French extreme right, where the 60th Reserve Division withdrew easily from Mailly to Villiers-Herbisse, while de l’Espée’s cavalry received strong support from the neighbouring army. On their east flank, therefore, the Saxons had to move with care. On their right, the Prussian Guard had been attracted westward, and there checked, at 4 p.m., by an attack of portions of the 9th Corps. The Saxons had progressed more easily, and had overrun the Prussians by several miles, thus prolonging the flank at which Foch intended to strike. There was no “fissure” at this time, but rather an overlapping; when, on the following day, a real gap opened between Bülow’s and Hausen’s Armies (on the Epernay and Châlons roads respectively), the retreat was too fast for the French to take advantage of it.

Foch’s design was the classic combination of flank and frontal attack. Grossetti was to drive east-north-east from Linthes–Pleurs, beside the main road and railway, toward Fère Champènoise, while, on his left, Dubois gave what aid he could in the same direction, and Eydoux came up from the south. It was to be the same famous manœuvre that Maunoury and the British had commenced three days before, without immediate success, but from which the whole “effect of suction,” with its momentous consequences, had arisen. Thanks to those three days of heroic effort and sacrifice, Foch’s success was instant and complete, though it was not such as the fables have it.69 Indeed, the enemy did not wait for the assault. He bolted. A doubtful story goes that a German aviator observed the approach of Grossetti’s columns, and gave Von Bülow’s Staff timely warning. The truth appears to be that the German retreat had been ordered between 3 and 5 p.m. At 6, under a red sunset, the 42nd Division arrived, and, supported by three, later increased to five, groups of artillery, moved slowly forward from the line Linthes–Linthelles, to bivouac near Pleurs.70 The 9th Corps alone came into touch with the enemy; and a rearguard resistance was enough to impede its hastily re-formed ranks. At daybreak on the 10th, the 34th Brigade entered Fère Champènoise, which had been evacuated the previous evening, picking up 1500 stragglers; while the 42nd Division was occupying Connantre, where 500 men of the Grenadier Guards were made prisoner at the château. As Grossetti’s columns crossed the hills in the dawn-light, the air was poisonous with rotting humanity, and spectral forms arose begging for a cup of water. They were men wounded in the surprise of the 8th who had lain in the open for nearly three days.

The front of the 9th Army was restored; and, weary but exultant, it prepared to go forward to the general victory. Whether, in the end, the movement of the 42nd Division counted for anything in this result, we can know, if ever, only when the German archives are opened. The chief factor lay not in the form of any particular manœuvre, but in the sheer persistence of the French centre. Foch and his men won by Nogi’s “quarter of an hour.”

CHAPTER VIII

FROM VITRY TO VERDUN

I. The Battle of Vitry-le-FrançoisIn the original design of the whole battle, the action of the right or eastern half of the Allied crescent was to be reciprocal to that of the left—while the centre held, Sarrail was to strike out from the region of Verdun westward against the flank of the Prince Imperial, as Maunoury struck out eastward from the region of Paris against that of Kluck. Something of this intention came into effect; but it was much modified by two circumstances. In the first place, General Joffre was driven both by major opportunity and by penury of means to make a choice. He decided that Verdun rather than Paris must run the greater risk, that Kluck’s headlong advance made the west the chief theatre for his offensive; and, to make sure on the west, he further weakened the eastern armies. It was, then, on terms of something less than equality of numbers that Sarrail and de Langle had to meet the Crown Prince, the IV Army, and the Saxon left, with their greatly superior equipment. Secondly, the danger beyond the Meuse could not be ignored; and anxiety on this score necessarily handicapped Joffre’s plan. The German idea was to cut Verdun off on either side: no direct attack was made upon the fortress, the Crown Prince proceeding around the entrenched camp by the west, while the Lorraine armies approached on the east and the IV Army swept over the empty flats of Champagne. On September 5, the German V Army, coming down both sides of the Argonne, had reached the open country south of the forest of Belnoue, that is, from 20 to 30 miles south-west of Verdun. It was, doubtless, expected that the Meuse fortress would be abandoned, as, indeed, it must have been had the French retreat continued longer. Stopped as it was, the Crown Prince awoke from his dream of making a new and greater Sedan between Dijon and Nancy to find himself under the necessity of forming a double front, toward the east and the south, a very unfavourable position in which to continue an offensive, to say nothing of the possibility of defeat. So far, good; but the situation was anything but secure. The French were perilously fixed on both sides of the Meuse in a long, sharp salient which had to be defended on three sides. Maunoury and the British, on the west, had escaped any danger of envelopment before the battle began. Without a battalion to spare, Sarrail and Langle stood throughout the struggle, the former with his back, the latter with his flank, to a wall that might give way at any moment. Even a small piercing of the French line between Verdun and Nancy would have involved the fall of the whole salient; while a still more disastrous realignment must have followed a failure of Castlenau and Dubail between Nancy and the Vosges.

In these circumstances, Sarrail could not produce, Langle had not the benefit of, such an “effect of suction” as governed the issue farther west. If the struggle could not be harder, it was more protracted. Partly because it became, when the French reinforcements arrived, a death-grapple of nearly equal masses—more or less than 400,000 men on either side—with little opportunity for manœuvre, partly because it occurred over obscure countrysides, it has not been adequately appreciated. It is, however, no less important than the battles of the left and the centre; for, if there was involved in them the fate of the capital, here not only Verdun, but Nancy and Toul, with the armies of the eastern frontier, were in the scales. Langle and Sarrail share equally with Gallieni and Maunoury, French, d’Espérey, and Foch the honours of the total victory.

The theatre of this part of the conflict forms a triangle, Vitry–Verdun–Bar-le-Duc, whose base is extended on the west to the Camp de Mailly, on the east to the hills on the farther bank of the Meuse. It is naturally divided into two sectors of very different character: (1) the left, or western, stretching from Mailly to near Revigny, in which the French 4th Army had to meet on a level front the Saxon left and the IV Army of the Duke of Würtemberg; (2) the right, or eastern, including the southern Argonne, the salient of Verdun, and the Heights of the Meuse, held by Sarrail’s 3rd Army against the V Army of the German Prince Imperial and a force from the Army of Metz. Both French groups had been greatly weakened to help other commands, Langle giving his 9th and 11th Corps to form Foch’s Army, while Sarrail surrendered the 42nd Division to Foch, and the 4th Corps to Maunoury. These transfers, necessary to provision the Generalissimo’s offensive, were compensated just, and only just, in time; thanks to a better outlook on the eastern frontier, Langle de Cary received the 21st Corps from the Vosges on September 9, and on the 8th Sarrail received the 15th Corps from Lorraine, closing with it an alarming gap between the 3rd and 4th Armies. Sarrail then had about ten divisions to the Crown Prince’s twelve; Langle’s force was also slightly outnumbered.

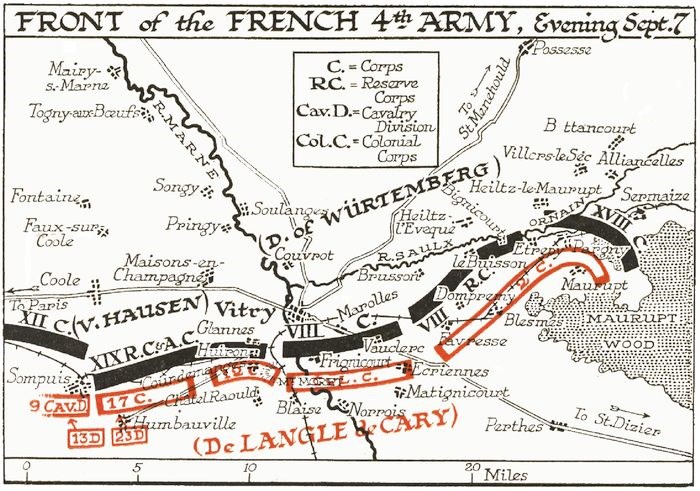

FRONT of the FRENCH 4th ARMY, Evening Sept. 7

On the evening of September 5, Langle’s front stood thus: On his left, the 17th Corps faced the Saxon XIX Corps between the moorland camp of Mailly and the Sommesous–Vitry railway. At his centre, across what may be called the delta of Vitry-le-François, a wide alluvial plain where the merged waters of the Ornain and the Saulx join the Marne, some elements of the 12th Corps and the Colonial Corps stood against the VIII Corps, active and reserve, of the IV Army. Vitry, an important junction of railways, roads, and waterways, is completely dominated by the hills to the north of the delta; and the 12th Corps, to which its defence would have fallen, had been so punished during the retreat that the greater part of it had to be withdrawn to the Aube for reconstitution on the evening of September 5. The Germans, therefore, occupied the town without much difficulty, and rapidly gathered behind it a strong force of artillery. While the French thus lost the cover of the Saulx and the Marne-Rhine Canal, they could still fall back upon the St. Dizier Canal and the Marne. The centre front, at the beginning of the battle, ran from the Mailly hills at Humbauville, through the villages of Huiron, Frignicourt, Vauclerc, and Favresse, to Blesmes railway junction. On Langle’s right, the 2nd Corps had passed the Saulx and its tributary the Ornain, and the Marne-Rhine Canal, leaving only advanced posts on the north of the valley, toward Revigny. To it were opposed Duke Albrecht’s VIII Reserve and XVIII Active Corps. The German programme was to break through by Vitry and Revigny into the upper valleys of the Seine, Aube, Marne, and Ornain. Langle’s orders were to try to make headway northward, in co-ordination with Sarrail’s attack toward the west. In fact, he was barely able to hold his ground until successes on either side relieved the pressure.

Happily, the German Command had not discovered the weakness of the junction between Foch’s and Langle’s forces; and the Saxons did not at first prove formidable. The 17th Corps was, therefore, able on September 6 to make a short advance west of Courdemanges, nearly to the railway. At the centre, the remaining battalions of the 12th Corps and Lefebvre’s Colonials were attacked violently in the morning. Huiron and Courdemanges, at the foot of the hills, were lost, but retaken during the evening. The three delta hamlets of Frignicourt, Vauclerc, and Ecriennes were also lost, the last two to IV Army regulars who had crossed the St. Dizier road and canal. On the right, the enemy forced the Marne-Rhine canal west of Le Buisson; and for a moment there was a danger of the Colonials being cut off from the 2nd Corps. To fill the breach, General Gerard transferred a brigade of the 4th Division from Pargny to near Favresse. Perhaps because of the consequent weakness of the right of the 2nd Corps, it could not hold the line of the canal from Le Buisson to Etrepy; and Von Tchenk’s XVIII Corps entered Alliancelles, 5 miles west of Revigny, and crossed the Ornain, in the afternoon. Reinforced by his Reserve, Tchenk pushed his advance on the following day, September 7, seizing Etrepy village, where the Saulx and Ornain join across the Rhine canal, at dawn, and Sermaize a few hours later.

Langle was here faced with a grave danger. His centre was still holding pretty well: Huiron was again lost, but the Colonials had recovered Ecriennes. On his left, the 17th Corps slightly improved its position, albeit the hazardous thinness of this part of the French front could not be much longer concealed. It was for his wings, therefore, that he was most anxious; and thither the two promised corps of reinforcements, the 15th and 21st, were directed. The 15th reached the right, to prolong Sarrail’s line, just in time. The enemy had, at a heavy cost, passed the Saulx-Ornain valley, with its many lesser water-courses, and had reached the edge of the wooded plateau of Trois-Fontaines, beyond which, ten miles south of Sermaize, lay the important town of St. Dizier. To break through thus far would be to cut off Sarrail at Bar-le-Duc from Langle at Vitry-le-François; it would be the doom of Verdun, and probably of the French centre. The greatness of the stake, the bitterness of the disappointment, afford the only explanation of the abnormal savagery shown by the Crown Prince’s troops in this region.

On September 8, the fighting reached its fiercest intensity. Tchenk pressed furiously his attack against and around Pargny, which his men entered at 5 p.m., after suffering heavy losses. Maurupt was also taken, but Gerard quickly recaptured it. The crisis, though not the struggle, was over with the arrival of the 15th Corps between Couvonges and Mognéville, threatening Tchenk’s left flank if he should attempt any farther advance. At the centre, a reconstituted half of the 12th Corps and the Colonial Corps were engaged in desperate combats. Courdemanges, Ecriennes, and Mont Moret fell in the morning; but the hill was retaken at nightfall. Several times driven out of Favresse, a brigade of the 2nd Corps finally held the village, and arrested the progress of the VIII Reserve Corps towards Blesmes railway junction. With constant violence of give and take, these positions were little changed on the following day. On the left, two regiments of the 17th Corps, pending the arrival of the other half of the 12th (23rd Division), bore throughout the 8th the onset of a fresh Saxon Division (xxiii of the XII Reserve Corps) to the west of Humbauville; while the remainder of the 17th Corps fell back a little before the XIX Corps, but advanced anew in the afternoon. In the evening, the balance was more than restored by the appearance of Baquet’s Division of the 21st Corps at the extreme left of the army, which next day (September 9) drove the Saxon right back in disorder toward Sommesous, liberating Humbauville, and enabling the 17th Corps also to gain ground. The other Division of the 21st Corps (43rd) had now reached the scene; and, on the 10th, Langle was able to make a strong offensive on this side, in association with Foch’s pursuit of the retreating Saxons.

II. Sarrail Holds the Meuse SalientThe French 3rd Army, when Sarrail took over its command from Ruffey on August 30, was a thing of shreds and patches. The 42nd Division of Sarrail’s own 6th Corps was being sent to Foch, leaving behind two other divisions, and a brigade of a third which had been broken up. The 4th Corps was about to leave for Paris, to take part in the battle of the Ourcq. There remained the 5th and the diminished 6th Corps, General Paul Durand’s Group of Divisions of Reserve (67, 75, and 65), formerly under Maunoury, the 72nd Reserve Division, forming part of the garrison of Verdun, and the 7th Cavalry Division. Verdun depending directly upon General Headquarters, Coutanceau and Heymann, the governor and the divisionaire, were not subject to Sarrail’s orders; but they co-operated admirably. Yet another southron, Sarrail was fifty-eight years old, a tall, slight figure, with (at that time) short white beard and moustache, blue eyes, and a gentle manner bespeaking the scholar and thinker rather than the man of action he proved himself to be. After service in Tunis and with the Foreign Legion, he had been advanced by Generals André and Picquart, and rose by steady stages from colonel in 1905 to corps commander. Across the mists of more painful days, I recall the strong impression he made upon me when I first met him at Verdun in December 1914.

From near the frontier, the 3rd Army had fallen back, at the end of August, westward to the Meuse between Stenay and Vilosnes, leaving the reserve group and garrison troops to make a thin line of defence on the east of the river, just beyond the radius of the entrenched camp and the edge of the Meuse Heights from Ornes to Vigneulles. “Entrenched camp” is the conventional name; but there were no serious entrenchments in those days, and scarcely any, as I can testify, three months later. The forts and thickly-wooded hills were sufficient, with the field army free, to determine the German Grand Staff to leave Verdun, as it was leaving Paris, aside. The French, however, could yet have no certainty on this score. During the first days of September, the 5th and 6th Corps pivoted around the west of Verdun; and, when they had completed the semicircle, the problem had to be faced. The hazard of the old fortress was no mere matter of sentiment. Its fall would mean the loss of all it could contribute to the contemplated attack on the enemy’s flank, and of a great strength of artillery and munitions that could not be removed, as well as of a formidable position. On the other hand, there lay Joffre’s plan, and the reasoning that had saved the British Army from internment at Maubeuge. The Generalissimo’s orders were express: the 3rd Army must keep its liberty, and must, accordingly, retire to the north of Bar-le-Duc, and possibly as far as Joinville. It was not only Verdun, but his power of threatening the German flank, that Sarrail hoped to save. He resolved, therefore, to give ground as slowly as possible, keeping his right in touch with the fortress to the last moment, and to risk, up to a certain point, a breach of contact with de Langle de Cary. At daybreak on September 6, his forces were ranged over the broadly-rolling fields and moorlands, facing westward, as follows:

Right.—Several regiments of the Verdun garrison were coming into line about Nixéville, and the three reserve divisions were spread thence along the Verdun–Bar highroad (afterwards famous as the “Via Sacra”) and narrow-gauge railway as far as Issoncourt, having before them the German XVI Active Corps reinforced some hours later by the VI Reserve.

Centre.—The 6th Corps extended through Beauzée south-westward to near Vaubécourt, with d’Urbal’s cavalry about Lisle-en-Barrois, facing the German XIII Corps.

Left.—The 5th Corps stood across the path of the German VI and part of the Duke of Würtemberg’s XVIII Corps among the villages north of Revigny, from Villotte to Nettancourt.

Although the dispositions of the German V Army—one corps of which was detained 10 miles north, and another a like distance west, of Verdun—at this juncture do not suggest over-confidence, an order found on the field shows that the Crown Prince now believed himself sure of a dramatic victory. At 8 p.m. on Saturday the 5th, instructions had been issued for the XVI, XIII, and VI Corps (in this order from east to west), with the XVIII Reserve on their right, to drive resolutely south, and to seize Bar-le-Duc and the Marne crossings to and beyond Revigny, while the IV Cavalry Corps exploited the breach between Sarrail and Langle’s forces, and hurried on “on the line Dijon–Besançon–Belfort.” As a whole, this design at once failed. The German advance had hardly begun when Heymann’s and Durand’s reservists, on the north, threatened its line of supply by an attack toward Ville-sur-Cousance, St. André, and Ippecourt; while, at the centre, the 6th Corps pushed toward Pretz, Evres, and Sommaisne. The small advantages gained were soon negatived, and at night the line was back at Rampont, Souhesmes, Souilly, Seraucourt, and Rembercourt; but a half of the Crown Prince’s units were held, if not crippled. This must have been all the more irritating to him because of the rapid success of his VI Corps and the IV Army. During the morning, in fact, the French left was driven out of Laheycourt, Sommeilles, and Nettancourt, then from Brabant and Villers-aux-Vents, and before night from Laimont and the market-town of Revigny. The Crown Prince had reached the Marne just as Kluck was beginning to retire from it. General Micheler and the 5th Corps, mourning many of their men and a divisional chief, General Roques, but cheered to think that the first reinforcements from Lorraine would arrive on the morrow, drew together their ranks at Villotte, Louppy, and Vassincourt.