полная версия

полная версияПолная версия

The Battle of the Marne

On September 8, the British Expeditionary Force, steadily gathering momentum, reached, and in part crossed, the Petit Morin, taking their first considerable number of prisoners, to the general exhilaration. On the left, the 3rd Corps advanced rapidly to the junction of that river with the Marne; but the enemy had broken the bridges at La Ferté-sous-Jouarre, and held stubbornly to their barricades on the north bank through this night and the following day. Farther up the deep and thickly-wooded valley, the 2nd Corps had some trouble between Jouarre and Orly; while, on the right, the 1st Corps, after routing the German rearguards at La Trétoire and Sablonnières, made the passage with the aid of a turning movement by some cavalry and two Guards battalions of the 1st Division.

The orders of this day for the 6th Army were to attack on the two wings—Drude’s Algerian Division (relieving the exhausted 56th Reserve and the Moroccan Brigade), with the 55th Reserve, on the right, towards Etrepilly and Vareddes; the 61st Reserve Division, General Boëlle’s 7th Division, and Sordêt’s cavalry, on the left—while the 7th Corps stood firm at the centre, and, south of the Marne, the 8th Division pressed on from Villemareuil toward Trilport, in touch with the British. For neither side was the violence of the struggle rewarded with any decisive success. On the French right, the Germans had more seriously entrenched themselves, and had much strengthened their artillery. Lombard’s Division of the 7th Corps was heavily engaged all day at Acy; at night the enemy still held the hamlet, while the chasseurs faced them in the small wood overlooking it. On the left, the 7th Division of the 4th Corps had no sooner come into action than it had to meet a formidable assault by the IV Active Corps. This was repulsed; but the Cavalry Corps seems to have been unable to take an effective share in the battle. During the afternoon, German troops occupied Thury-en-Valois and Betz. Reinforcements were continually reaching them. At nightfall, although Boëlle’s divisions were resisting heroically, and even progressing, the outlook on the French extreme left, bent back between Bouillancy and Nantheuil-le-Haudouin, had become alarming. Maunoury, however, obtained from General Gallieni the last substantial unit left in the entrenched camp of Paris, the 62nd Division of Reserve, and gave it instructions to organise, between Plessy-Belleville and Monthyon, a position to which the 6th Army could fall back in case of necessity. In course of the night, Gallieni sent out from Paris by motor-cars a detachment of Zouaves to make a raid toward Creil and Senlis. It was a mere excursion; but the alarm caused is very comprehensible when the extreme attenuation of the supply lines of the German I Army is remembered. Marching 25 miles a day, and sometimes more, it had far overrun the normal methods of provisioning. During the advance, meat and wine had been found in plenty, vegetables and fruit to some extent, bread seldom; here, in the Valois, the army could not feed itself on the country, and convoys arrived slowly from the north. Artillery ammunition was rapidly running out. Hunger quickly deepens doubt to fear.

But Maunoury’s men were at the end of their strength. On the morning of September 9, a determined attack by the IV Active Corps, supported by the right of the II, was delivered from Betz and Anthilly. The 8th Division had been summoned back from the Marne, to be thrown to the French left. Apparently it could not be brought effectively into this action; and the 61st and 7th Divisions and the 7th Corps failing to stand, Nanteuil and Villers St. Genest were lost, the front being re-formed before Silly-le-Long. “A troop which can no longer advance must at any cost hold the ground won, and be slain rather than give way.” Such a summons can only be repeated by a much-trusted chief. Maunoury repeated it in other words. Thousands of men, grimy, ragged, with empty bellies and tongues parched by the torrid heat, had already gone down, willingly accepting the dire sentence. Few of them could hear or suppose that the enemy was in yet extremer plight. So it was. Early in the morning, Vareddes and Etrepilly had been found abandoned; greater news had been coming in for hours to Headquarters—some of it from the enemy himself by way of the Eiffel Tower in Paris, where the French “wireless” operators were picking up the conversations of the German commanders. Marwitz was particularly frank and insistent; his men were asleep in their saddles, his horses broken with overwork. He was apparently too much pressed to wait for his message to be properly coded. By such and other means, it was known that Kluck and Bülow were at loggerheads, that, even on the order of Berlin, the former would not submit himself to his colleague, and that, in consequence, Bülow in turn had begun to retreat before Franchet d’Espérey.

CHAPTER VII

THE “EFFECT OF SUCTION”

I. French and d’Espérey strike NorthThe unescapable dilemma of the Joffrean strategy had developed into a second and peremptory phase. In deciding to withdraw from the Brie plateau and the Marne, rather than risk his rear and communications for the chance of a victory on the Seine, Kluck, or his superiors, had, doubtless, chosen the lesser evil. The marching wing of the invasion was crippled before the offensive of the Allies had begun; but Gallieni’s precipitancy had brought a premature arrest upon the 6th Army. Beside this double check, we have now to witness a race between two offensive movements—Bülow and Hausen pouring south with the impetuosity of desperation, while, along their right, the British Force and the French 5th Army struck north between the two western masses of the enemy with the fresh energy of an immense hope. Which will sooner effect a rupture?

Logically, there should be no doubt of the answer. Kluck was mainly occupied with Maunoury; Bülow, with Foch. Between them, there was no new army to engage the eight corps of Sir John French and Franchet d’Espérey. The cavalry and artillery force of Marwitz and Richthofen, strong as it was, could do no more than postpone the inevitable—always provided that Maunoury and Foch could hold out. Every day, the pull of Kluck to the north-west and of Bülow to the south-east must become more embarrassing. French writers have applied an expressive phrase to the influence of this pull—“effet de ventouse,” effect of suction—though hardly appreciating its double direction. The maintenance of a continuous battle-line is axiomatic in modern military science. It follows from the size of the masses in action, the difficulty, even with steam and petrol transport, of moving them rapidly, and their dependence upon long lines of supply. The soldier bred upon Napoleonic annals may long for the opportunity of free manœuvre; all the evolution of warfare is against his dream. An army neither feeds nor directs itself; it is supplied and directed as part of a larger machine executing a predetermined plan. Superiority of force is increased by concentration, and achieves victory by envelopment of the enemy as a whole, or his disintegration by the piercing of gaps, a preliminary to retail envelopment or dispersal. A course which loses the initial superiority and requires a considerable change of plan is already a grave prejudice; when to this is added a necessary expedient leading to an extensive disturbance of the line, prudence dictates that the offensive should be suspended until the whole mass of attack has been reorganised in view of the new circumstances. The German Command dare not risk such a pause. It persisted; and the penalty lengthened with every hour of its persistence. The more Kluck stretched his right in order to cover his communications by Compiègne and the Oise valley, the wider became the void between his left and the II Army, constantly moving in the opposite direction. When French and d’Espérey found this void, a like difficulty was presented to Bülow—to be enveloped on the right, or to close up thither, leaving a breach on his other flank, which the Saxon Army would be unable to fill. Thus, Maunoury’s enterprise on the Ourcq, though falling short of full success, produced a series of voids, and, at length, a dislocation of the whole German line, which was only saved from utter disaster by a general retreat.

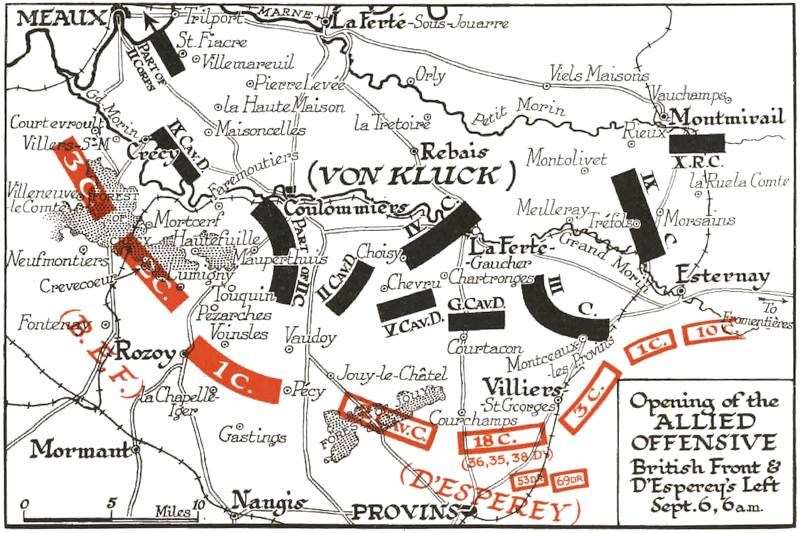

Opening of the ALLIED OFFENSIVE

British Front & D’Espérey’s Left

Sept. 6, 6 a.m.

General Franchet d’Espérey, who had been brigadier in 1908, divisional commander in 1912, a gallant and energetic officer now fifty-eight years of age, successful with the 1st Corps at Dinant and St. Gerard in Belgium, and in the important battle of Guise, had, on September 3, succeeded Lanrezac at the head of the largest of the French armies, the 5th. Its task—in touch with Foch on the right, and with the British, through Conneau’s cavalry corps, on the left—was to press north toward Montmirail, against Kluck’s left (III and IX Corps, and Richthofen’s cavalry divisions) and the right wing of Bülow (VII Corps and X Reserve Corps). In later stages of the war, the junction of two armies often showed itself to be a point of weakness to be aimed at. With four active corps and three divisions of reserves in hand, d’Espérey had, even before the German withdrawal began, a considerable advantage—indicating Joffre’s intention that it should be the second great arm of his offensive, that which should make the chief frontal attack. On the other hand, the enemy held strong positions along the Grand Morin, and, behind this, along the Vauchamps–Montmirail ridge of the Petit Morin. During their retreat the Allies had used the opportunity offered by the valleys of the Marne and its tributaries for delaying actions; these streams were now so many obstacles across their path. The first French movement, on September 6, was powerfully resisted. On the left, the cavalry occupied Courtacon.64 At the centre, the 18th and 3rd Corps co-operating (prophetic combination—Maud’huy, Mangin, and Petain!), the villages of Montceaux-les-Provins and Courgivaux, on the highroad from Paris to Nancy, which was, as it were, the base of the whole battlefield, were taken by assault. On the right, the 1st Corps was stopped throughout the forenoon before Chatillon-sur-Morin by the X Reserve Corps. D’Espérey detached a division, with artillery, to make a wide detour and to fall, through the Wood of La Noue, upon the German defences east of Esternay. Thus threatened, the enemy gave way; and the market-town of Esternay was occupied early on the following morning. The 10th Corps continued the line toward the north-east, after suffering rather heavy losses beyond Sezanne.

On the morning of September 7, the air services of the 5th Army reported the commencement of Kluck’s retreat; and soon afterwards a corresponding movement of Bülow’s right was discovered to be going on behind a screen of cavalry and artillery, supported by some infantry elements. D’Espérey had no sooner ordered the piercing of this screen than news was brought in of the critical position of the neighbouring wing of Foch’s Army, the 42nd Division and the 9th Corps, through which Bülow’s X and Guard Corps were trying to break, from the St. Gond Marshes toward Sezanne. He at once diverted his 20th Division to threaten the western flank of this attack (which will be followed in the next section) about Villeneuve-lès-Charleville. Meanwhile, rapid progress was being made on the centre and left of the 5th Army. Between Esternay and Montmirail extend the close-set parklands called the Forest of Gault, with smaller woods outlying, a difficult country in which many groups of hungry German stragglers were picked up during the following days. Through this district, the 1st Corps and the left of the 10th, with General Valabrègue’s three divisions of reserves behind, beat their way; while, farther west, in the more open but broken fields between the Grand and the Petit Morin, the 18th and the 3rd Corps made six good miles, to the line Ferté Gaucher–Trefols. More than a thousand prisoners were taken during the day, with a few machine-guns and some abandoned stores.

We have seen (pp. 124–5, 131) the British Expeditionary Force at the beginning of a like novel and exhilarating experience. Its five divisions, having seized Coulommiers on the night of September 6, had pressed on to the Petit Morin, and, from its junction with the Marne eastward to La Trétoire, where obstinate opposition was offered, had secured the crossings. D’Espérey’s left wing thus found its task lightened; and the 18th and 3rd Corps were ordered to sweep aside the remaining German rearguards, and to strike across the Petit Morin on either side of Montmirail. September 8 was thus a day rather of marching than fighting, except at Montmirail, on whose horse-shoe ridge the enemy held out for some hours.65 In the evening, General Hache entered the picturesque town, and set up his quarters in the old château where Bülow’s Staff had been housed on the previous day. On the left, Maud’huy pushed the 18th Corps by Montolivet over the Petit Morin, and after a sharp action took the village of Marchais-en-Brie. On the right, the 1st Corps was checked at Courbetaux and Bergères, the German VII Corps having come into line; so that the 10th Corps, between Soigny and Corfelix, had to turn north-westward to its assistance. This was scarcely more than an eddy in the general stream of fortune. The moral effect of a happy manœuvre goes for much in the result. The British and d’Espérey’s men forgot all their sufferings and weariness in the spectacle of the enemy yielding. British aviators reported Kluck’s columns as in general retreat, certain roads being much encumbered. Bülow had necessarily withdrawn his right to maintain contact; his centre and left must follow if the pressure were continued.

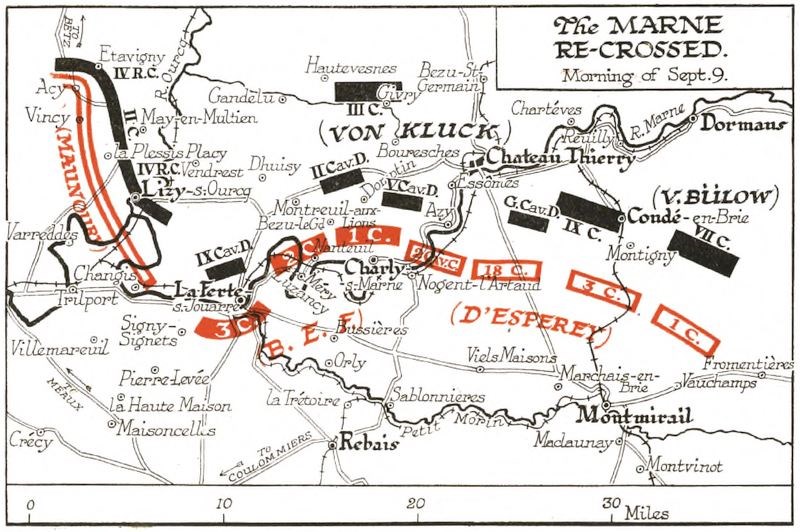

The hour of decision approached. During the morning of Wednesday, September 9, Sir John French’s 2nd and 1st Corps crossed the Marne at Luzancy, Sââcy, Nanteuil, Charly, and Nogent-l’Artaud. This part of the valley was scarcely defended; and a brigade of the 3rd Division had progressed 4 miles beyond it by 9 a.m. Anxious news for the German Staff. Unfortunately, our right was arrested until afternoon by a threat of attack from Château-Thierry; and, lower down the river about La Ferté, the 3rd Corps, still represented only by the 4th Division and the 19th Brigade, was stopped until evening before the broken bridges and rifle-parapets on the northern bank. Some guns then carried over near Changis bombarded the German artillery positions beyond the Ourcq, a notice to quit that had prompt effect. Château-Thierry was left to the French 18th Corps, which occupied the town that night. Meanwhile, Smith-Dorrien and Haig entered the hilly country about Bezu, Coupru, and Domptin, on the road from Château-Thierry to Lizy-sur-Ourcq. Marwitz vainly essayed to obstruct the northward movement. Beaten in an action near Montreuil-aux-Lions, he informed Kluck that he could do no more, and hurried back to the line of the little river Clignon, about Bussiares and Belleau, which were reached by 4 p.m. A little later, British Aviators brought in word that the enemy had evacuated the whole angle between the east bank of the Ourcq and the Marne, and that, on the other hand, the withdrawal of the German I Army was creating a void beyond Château-Thierry: the cavalry of Richthofen, sent thither by Bülow, was in the same predicament as that of Marwitz farther west. At daybreak on September 10, Pulteney’s Corps left the Marne behind. Meeting no serious resistance, the British crossed the Clignon valley, and by evening occupied La Ferté-Milon, Neuilly-St. Front, and Rocourt.

These were marching days for the 5th Army. Conneau’s cavalry, reinforced by an infantry brigade and extra batteries, passed the Marne at Azy on the 9th, and, harrying Bülow’s right flank, reached Oulchy-le-Château next day. The 18th Corps, with the reserve divisions in support, pushed on from Château-Thierry toward Fère-en-Tardenois; and the 3rd Corps, which had occupied Montigny, half-way between Montmirail and the Marne, on the 9th, forced the passage, under heavy fire from the hills at Jaulgonne, on the 10th. The 1st Corps had a heavier task. Having progressed as far as the Vauchamps plateau, it was wheeled back to the south-east to help the 10th Corps, which d’Espérey had transferred to Foch’s Army of the centre, now in the gravest peril.

II. Battle of the Marshes of St. GondWhile the 6th Army, within sight of the Ourcq, was suffering its great agony, while the “effect of suction” was showing itself in the Anglo-French pursuit of Kluck, very different were the first results at the centre of the long crescent of the Allied front. Kluck was saved by his quick resolution, together with Marwitz’s able work in covering the rear. Bülow was in no such imminent danger. His communications with the north were at first perfectly safe. The situation of his right wing, which must either fall back or lose contact with the I Army, was awkward; but, doubtless, Kluck’s success would soon re-establish it. The circumstances indicated for the remainder of the II Army and the neighbouring Saxon Corps an instant attempt to break through the French centre, or at least to cripple it, and, with it, all Joffre’s offensive plan. The very strategic influence which helped the British and d’Espérey, therefore, at first threw a terrible burden upon Foch and the “detachment” which on September 5 was renamed the “9th Army”; yet it was by this same influence that, in the end, though by the narrowest of margins, he also won through.

The MARNE RE-CROSSED.

Morning of Sept. 9.

The theatre of this struggle is the south-western corner of the flat, niggardly expanse of La Champagne Pouilleuse, lying between the depression called the Marshes of St. Gond and the Sezanne–Sommesous railway and highroad. It is very clearly bounded on the west by the sharp edge of the Brie plateau; on the east it is bordered by the Troyes–Châlons road and railway. Sezanne on the west, and Fère Champènoise at the centre, are considerable country towns; the right is marked by the permanent camp of Mailly. To the north of Sezanne, the hill of Mondemont, immediately overlooking the marshes and the plain, and the ravine of St. Prix, on the Epernay road, where the Petit Morin issues from the marshes and breaks into the plateau, are key positions. The Marshes of St. Gond (so called after a seventh-century priory, of which some ruins remain) witnessed several of the most poignant episodes of Napoleon’s 1814 campaign “from the Rhine to Fontainebleau.” They were then much more extensive. Between the villages of Fromentières and Champaubert, there survives the name, though little else, of the “Bois du Desert,” where 3000 Russian grenadiers are said to have been slain or captured by Marmont’s cuirassiers, while hundreds of others were drowned. A month later, Blücher was back from Laon attacking on the same ground; and Marmont and Mortier were in full retreat along the road to Fère Champènoise. Pachod’s national guards, the “Marie Louises,” turned north to the marches of St. Gond as to a refuge. The Russians and Prussians surrounded them; and only a few of the French lads escaped by the St. Prix road. To-day the marshes are largely reclaimed and canalised; but this clay bed, extending a dozen miles east and west, and averaging more than a mile in breadth, fills easily under such a rainstorm as fell upon the region on the evening of September 9, 1914, and at all times it limits traffic to the three or four good roads crossing it. The chief of these, from Epernay to Sezanne and Fère Champènoise respectively, pass the ends of the marshes at St. Prix and Morains; the former is commanded by Mondemont; the latter by Mont Août, near Broussy.

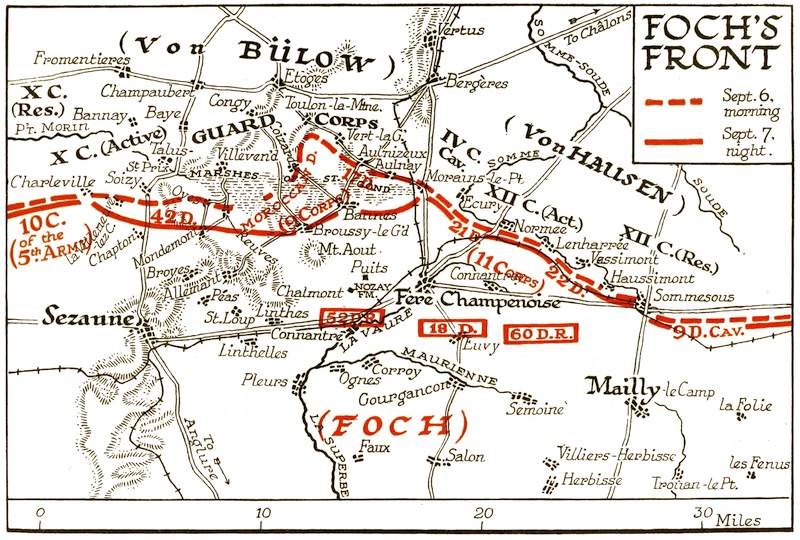

Was this “last barrier providentially set across the route of the invasion”66 forgotten? Joffre’s earlier plan did, indeed, involve the abandonment of all the plain extending to the Aube; the decision to stand on the line of the marshes was a consequence of Gallieni’s initiative. Foch’s Army had been carried beyond them in its retreat, but, fortunately, not far beyond. On the morning of September 5, advance columns of Bülow’s left had entered Baye; patrols had reached the Petit Morin bridge at St. Prix, and the north-centre of the marshes at Vert-la-Gravelle. A little more dash, and the Germans would have possessed themselves of all the commanding points. It was about 10 a.m. that Foch received the Generalissimo’s order closing the retreat: “The 9th Army will cover the right of the 5th Army, holding the southern passages of the Marshes of St. Gond, and placing a part of its forces on the plateau north of Sezanne.” Foch at once directed the appropriate movements; and, by the evening of September 5, the following positions were reached:

French Left.—Driven, back from St. Prix by forces belonging to Bülow’s X Active and Reserve Corps, the 42nd Division (General Grossetti) held the neighbouring hills from Villeneuve-lès-Charleville and Soisy to Mondemont.

Centre.—During the afternoon, Dubois advanced the 9th Corps (Moroccan Division and 17th Division) from Fère Champènoise to Broussy and Bannes, and thence pushed two battalions over the marshes to Toulon-la-Montagne, Vert-la-Gravelle, and Aulnizeux in face of the Prussian Guard Corps, the main body of which was at Vertus. The Blondlat Brigade of the Moroccan Division attacked Congy, but failed, and fell back on Mondemont. The 52nd Reserve Division was in support about Connantre.

French Right.—The 11th Corps (General Eydoux) rested on the east end of the marshes at Morains-le-Petit, and from here stretched backward along the course of the Champagne Somme to Sommesous, with the 60th Reserve Division behind it. They had before them the Saxon XII Active Corps and one of its reserve divisions. At Sommesous, General de l’Espée’s Cavalry Division covered a gap of about 12 miles between Foch’s right and de Langle de Cary’s left at Humbauville.

Thus, on the eve of the battle, the 9th Army, inferior to the enemy in strength, especially in artillery, presented to it an irregular convex front. Bülow was at Esternay on the west; Hausen was approaching the gap on its right flank; the centre was protruded uneasily to and beyond the St. Gond Marshes. The expectation of General Headquarters had, apparently, been that the German onset would fall principally on the right of the 5th Army. Foch was, therefore, instructed to give aid in that direction by pushing his left to the north-north-west, while the rest of his line stood firm until the pressure was relieved. In the event, these rôles were reversed: it was d’Espérey who had to help Foch. The original dispositions, however, had a certain effect upon the course of the battle. They gave the 9th Army a pivot on the Sezanne plateau; and the obstinacy with which this advantage was retained seems to have diverted the German commanders, till it was too late, from concentrating their force on the other wing, the line of attack from which the French had most to fear.

FOCH’S FRONT

Sept. 6, morning.

Sept. 7, night.

Foch was the offensive incarnate; but, on the morning of September 6th, he could do no more than meet, and that with indifferent success, Bülow’s attack upon his left-centre. He was weakest where the enemy was most strong: a large part of the French guns could not reach the field for the beginning of the combat; the 9th Corps, in particular, felt the lack of three groups of artillery it had left in Lorraine. Failing this support, the two battalions holding Toulon-la-Montagne were quickly shelled out of their positions. In vain Dubois, commanding the 9th Corps, ordered the Moroccan Tirailleurs to march on Baye, and the 17th Division to retake the two lost points. A crack regiment, the 77th, crossed the marshes and entered Coizard village, Major de Beaufort, cane in hand, on a big bay horse, at its head, crying to his men, shaken by rifle fire from the houses: “Forward, boys! Courage! It is for France. Jeanne d’Arc is with us.” The 2nd and 3rd battalions went on, and tried to climb Mount Toulon. The fighting continued all day, ending in a painful retreat to Mont Août through two miles of swampy ground, in which the men plunged up to the waist rather than risk the shell-ploughed causeway. The Guard followed as far as Bannes, and the X Corps occupied Le Mesnil Broussy and Broussy-le-Petit, where the French batteries arrested them. Small French detachments clung to Morains and Aulnay through the day and night; otherwise, the north of the marshes was lost. Against the left, Bülow was less successful. The 42nd Division and the Moroccan Division withstood repeated assaults of the X Corps at Soisy-aux-Bois and on the edge of the St. Gond Wood. The struggle, however, was most severe: Villeneuve, occupied on the evening of September 5, was lost at 8 a.m. on the 6th, recaptured an hour later, lost again at noon, and recovered at night. On the right, the 11th Corps had to evacuate Ecury and Normée under heavy fire; Lenharrée and Sommesous were partially in flames, but still resisted.