полная версия

полная версияThe Battle of the Marne

Unawed, in his quarters at Pleurs, Foch wrote the following order for the morrow:—“The General Commanding counts on all the troops of the 9th Army exerting the greatest activity and the utmost energy to extend and maintain beyond dispute the results obtained over a hard-pressed and venturesome enemy.” Many of the generals, lieutenants, and men may have thought these last words too highly coloured. Foch himself knew more of the real situation. He knew, as did Bülow, how gravely the latter was prejudiced by Kluck’s predicament. Already, the prospect had arisen of the I German Army being gripped by the closing vice of Maunoury and the British. Already, d’Espérey’s great force was moving north along Bülow’s flank toward Montmirail. Joffre’s masterstroke was revealed. Was the victory that Berlin and the armies counted as certain to slip away at the eleventh hour? For the first time in a triumphant generation, a German Army was in danger of defeat; nay, all the armies were in danger. Astounding change of fortune! The greycoat soldiery, dulling their weariness in the loot of cottages and farms, the subaltern officers, making free with the wine cellars of old manor houses, did not know it; but such was the fact. Their commanders were not the men easily to take alarm; yet, at this moment, alarm must have struck them.

III. Defence and Recapture of MondemontThe grand manœuvre of envelopment had failed. The alternative plan remained: to smash the French centre and roll up the lines on either side. On the morning of September 7, this effort began with a fierce onslaught across the ravine of the Petit Morin against the Sezanne plateau from Mondemont to Villeneuve.

On Foch’s extreme left, nothing was gained. The 42nd Division was now receiving perceptible support from the 10th Corps of the 5th Army, which during the day, as we have seen, completed the clearance of the Forest of Gault, to the west of Villeneuve. Toward Mondemont, however, the X Active Corps made some progress, throwing the defenders back to the western borders of Soisy, again taking Villeneuve, and reaching through the St. Gond Wood nearly to the hamlet of Chapton. The bare crest called the Signal du Poirier gave the German gunners an excellent platform, with views over a large part of the French lines. One of their chief targets was the château of Mondemont, a two-story mansion, dating from the sixteenth century, with pepper-pot corner towers, enclosing a large square courtyard. General Humbert had set up here his Staff quarters; but by noon the bombardment had become so severe that he had to leave it to advanced posts of the Moroccan Division, first, however, insisting on taking a proper lunch in the salle-à-manger with the trembling family. These were sent to the rear, and Humbert moved to the neighbouring château of Broyes. In a later stage of the war, Humbert struck me rather as the thinker, a quiet, keen intelligence, and a fine gentleman. At this earlier time, one of the youngest generals in the French Army, he appears rather as the man of spirited action. Beaming with gay confidence, he abounded in the gestes that the French soldier so loves. Once several members of his escort were killed by a shell exploding in their midst; like Grossetti, afterwards to be known as “the Bull of the Yser,” danger only stimulated him. “The Germans are bottled up,” he said; “Mondemont is the cork. It must be held at any price.” At 5 p.m., a combined attack, by parts of the 42nd and Moroccan Divisions, with the 77th regiment of the 9th Corps, was made with the object of freeing the Mondemont position. Little ground was gained, and the losses were very heavy; it was a momentary relief, no more.

At length the German Command recognised that the French defence was weakest toward and beyond Fère Champènoise, and that a simultaneous attack by both their wings, with most strength on the east, might shatter it. First, however, the flank of the Guard Corps along the marshes must be cleared. This preliminary occupied the whole of September 7. On the west, Oyes was taken during the morning in the advance on Mondemont. On the east, the French companies outlying at Morains and Aulnay had to abandon these villages at 8 a.m., under threat of being taken in reverse along the railway. Morains is only four miles by highroad from Fère Champènoise; and here the picked infantry of the Guard were striking at the junction of the 9th and 11th Corps, with solid Saxon regiments closing in upon the latter to the south-east. Seeing their danger, Radiguet and Moussy concerted a movement by which, during the afternoon, Aulnizeux was taken and the German advance checked. In the evening, at the third attempt, the enemy recovered the village; and in the last hours of the night his general offensive along the Sezanne and Fère roads began. It will be convenient to follow first the western arm of the attack.

At 3 a.m. on September 8, after a sharp cannonade, the French machine-gunners on Mondemont Hill observed spectral forms approaching in open order—these were advanced parties belonging to the X Corps, with some elements of the Guard. They were easily repulsed; and, immediately afterwards, the much-thinned ranks of the 42nd and Moroccan Divisions, with the 77th regiment of the 9th Corps, were launched anew towards St. Prix. Although Bülow had received reinforcements, and had placed more batteries between Congy and Baye, the Moroccans occupied Oyes and its hill and the Signal du Poirier by 8 a.m., while the left of the 42nd carried Soisy at the point of the bayonet. Unfortunately, the debacle that was happening coincidentally on Foch’s right put any exploitation of this success out of the question. A fresh defensive front had to be created south of the marshes, facing east; the 77th regiment was recalled to St. Loup in the middle of the afternoon for this purpose. The 42nd Division seems to have been shaken by this removal of a sorely-needed support; and Bülow, promptly advised of it, ordered his columns forward once more.

On an islet in the west end of the marshes, between the villages of Villevenard and Oyes, stand a Renaissance gateway and other remnants of the ancient Priory of St. Gond, and in their midst the humble dwelling of “the last hermit of St. Gond,” as M. le Goffic calls him, the Abbé Millard, corresponding member of the French Antiquarian and Archæological Societies. A victim of dropsy, the Abbé was laid up when the approach of the Germans was announced. “So, then,” he calmly remarked, “I shall renew my acquaintance with Attila.” His housekeeper, a typically vigorous Frenchwoman, would have no such morbid curiosity. “You have no parishioners but the frogs, Monsieur le Curé; and they can take care of themselves against your Attila. Come along”—and, bundling some valuables into a wheelbarrow, and giving Father Millard a stick, she carried him off into safety. As they left, a body of Senegalese sharpshooters came up, and began to build across the highway an old-fashioned barricade of tree-trunks, carts, and blocks of stone. “Some barbed wire and a continuous trench, such as the Germans use, would have been better,” remarks M. le Goffic; “but we remained faithful to our old errors, and, nearly everywhere, our men fought in the open or behind sheaves and tree trunks.”

After hours of an ebb-and-flow of bayonet charges and hand to hand combats, the French lost in succession Broussy-le-Petit, Mesnil-Broussy, Reuves, and Oyes—all the morning’s gain had vanished by nightfall. With the Germans entrenched a mile away, and only a single Zouave battalion in reserve, Humbert insisted that Mondemont must be held; and his corps commander, Dubois, desperately seeking to cover the void on his right with the 77th Regiment, told the officers that retreat was not to be thought of. Heavy rain fell during the evening, obstructing the movements of all the armies. On both sides, that night, the chiefs knew that the issue was a matter of hours, of very few hours. We saw in the first section of this chapter that, on the evening of September 8, the left of the 5th French Army had passed, and its centre reached, the Petit Morin, while the 10th Corps immediately threatened Bülow’s flank at Bannay, only 2 miles west of Baye. The “effect of suction” was working wonderfully. An order found during the day on a wounded officer, directing that the regimental trains should be drawn up facing north, showed the preoccupations of the German Staff. If the Guard and the Saxons could complete the rout of Foch’s right-centre, they might yet win through; but there was no longer a moment to spare, for Bülow had no force capable of long withstanding d’Espérey’s north-eastward thrust.

Against Foch’s left, Bülow played his last stake at daybreak on September 9. A whole brigade, marching from Oyes under cover of mist, brushed aside the two battalions of sharpshooters, mounted Mondemont hill, and seized the château and village, which were rapidly provided with a garrison and machine-guns. The 42nd Division was in course of withdrawal at this time, its place being taken by the 51st Division of the neighbouring army. Humbert still would not take defeat: borrowing two battalions of chasseurs from Grossetti, he sent them to the assault of the promontory. They failed. At about 10.30 a.m., the 9th Corps lost Mont Août, the stronghold of Foch’s centre, and fell back upon the lower hills between Allemant and Linthes. If the whole left and centre of the 9th Army were not to be swept, after its right, into the plain, the last footing on the Sezanne plateau must be held at any price. But how? Many companies of the Moroccan Division had lost all their officers and most of their men. The breakdown of his right had driven Foch to an extreme expedient which we will presently follow more closely—the transfer thither of the 42nd Division; all Grossetti could do for Humbert after his early morning failure, therefore, was to lend him his artillery for a couple of hours. From Dubois and his own corps, Humbert was able again to borrow the 77th Regiment. After a massed fire of preparation on the woods and slopes around the château of Mondemont by nine batteries, the hungry, haggard survivors of the 77th, divided into two bodies under Colonels Lestoquoi and Eon, approached the hill from the west and east, while four companies gathered to the south of the château as a storming force under Major de Beaufort.

We have already seen this only too chivalric officer defying the prime conditions of modern warfare in the capture of Coizard; here is a yet more pathetic exhibition of the ancient style of heroism. It was 2.30 of a bright afternoon, the air oppressive with heat, smoke, and dust. The commandant called a priest-soldier from the ranks, and asked him to give supreme absolution to the men who wished to receive it. They knelt, and rose. The major, putting on his white gloves, then gave the order to charge. Bugles sounded; the men ran forward “in deep, close masses,” shouting and singing. Many fell before reaching the garden of the château. De Beaufort, standing for a moment under a tree to consider the next step, was shot dead. A few men got through a breach in the garden wall, only to meet a rain of bullets from loopholes in the house. A score of officers (including Captain de Secondat-Montesquieu, a descendant of the great French writer) were lost, with a third of the effectives. At 3.30, Colonel Eon withdrew the remainder of the storming party.

For a breathing space only. The château was, in fact, besieged. Three field-guns were brought within 400 yards of it; and at 6 p.m. three companies advanced upon the quadrangle of buildings, four others upon the village, at the foot of the hill. Forty minutes later, Colonel Lestoquoi led his last remaining company forward, crying: “Come on, boys; another tussle, and we are there.” This time, château, park, farm, and churchyard, and finally the village, were carried. “I hold the village and the château of Mondemont,” Lestoquoi reported to General Humbert; “I am installing myself for the night.”

The battle of Mondemont was over; one wild ebb-wave, and the peace of nature’s fruitfulness fell for all our time upon the riven fields, the multitude of graves, the desolate marshes.

IV. Foch’s Centre brokenFar other and graver was the course of the eastern arm of the German attack, after the loss of the marsh villages by the French 9th Corps on September 7.

Dubois’ shaky line, along the south of the marshes, was continued eastward by the 11th Corps (including, now, the 18th Division) from near Morains to Normée, and this by the 60th Reserve Division, thence to Sommesous, and the 9th Cavalry Division, reaching out to the left of de Langle’s Army (the 17th Corps). These faced, respectively, the Prussian Guard Corps, the Saxon XII Active Corps, and part of its reserve. No great inequality, so far; but Bülow and Hausen were bringing up reinforcements, and preparing a terrible surprise. Throughout September 7, the Saxons had been hammering at Eydoux’ front along the Somme-Soude. Lenharrée, defended throughout the afternoon and evening by only two companies, became untenable during the night. All the officers had fallen, Captain Henri de Saint Bon last of them, crying to his Breton reservists of the 60th Division: “Keep off! Do not get killed to save me.” On entering the village, and seeing what had happened, the Saxon commander ordered his men to march before the French wounded, saying: “Salute! They are brave fellows.” So began the darkest episode, the nearest approach to a German victory, in the battle of the Marne.

An hour before—at 3 a.m. on September 8—their guns pushed forward under cover of darkness, the general assault by Bülow’s and Hausen’s armies had begun. It was well planned according to the information of those commanders, and, considering how serious an obstacle the marshes presented to their centre, remarkably conducted. On the west, the resolution of the defenders of Mondemont would have gone for nothing without the increasing support of d’Espérey’s 10th Corps. At the left-centre, the marshes gave Dubois sufficient cover to enable him to wheel half his force eastward. Beyond that, the conditions favoured the enemy, for the only main roads converged upon Fère Champènoise; and, if the French were driven back, a dangerous block would inevitably be produced. Against the extreme right, the Saxons were not in great force; and, on that flank also, the neighbouring French Army gave vital aid.

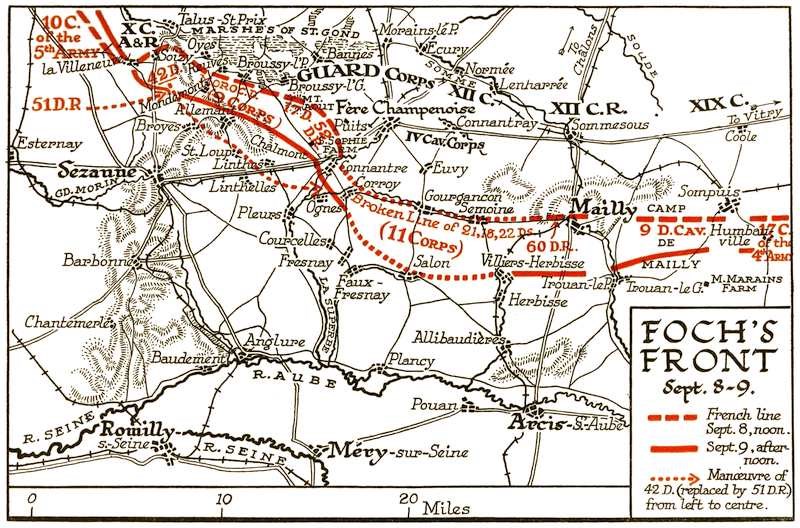

FOCH’S FRONT

Sept. 8–9.

So, in the misty dawn of September 8, the greycoats, picked Prussians and burly Saxons, swarmed forward, seeming to renew themselves irresistibly. Foch, talking to his Staff overnight, had exclaimed that such desperation suggested the need of compensating for ill fortune elsewhere; and now he opened a black day with a characteristic phrase of stubborn cheer: “The situation is excellent; I order you again vigorously to take the offensive.” The situation excellent! Foch would not use words of meaningless bravado; he may have been thinking of d’Espérey knocking at Bülow’s side door. At this hour (7 a.m.), he could not yet know that the loss of Lenharrée had been followed by the turning of two regiments of the 20th Division, and two others of the 60th Reserve Division, defending the passages of the Somme-Soude, and that the lines on either side were crumpling up. So it was. From a number of personal narratives, often contradictory and exaggerated, we can draw an outline of what occurred in the surprise of Fère Champènoise, without pretending to determine exactly where, or by what failing of exhausted men, the confusion originated.

Before Normée, outposts of the 11th Corps, scattered by the sudden fierceness of the onslaught, left uncovered the 35th Brigade (of the 18th Division), which lay bivouacked in the woods. One regiment, the 32nd, was surrounded, and only a half of its effectives, with a few junior officers, escaped. The 34th Brigade, behind it, had time to fall back without loss, through Connantre to Oeuvy, along with the survivors of the 35th. The remnants of the defenders of Lenharrée retreated toward Connantre, firing steadily. As far as Fère Champènoise, the chase ran fast along the four roads, from Bannes, Morains, Ecury, and Normée. In the little country town, crouched in a depression of the hills, and so indefensible, an army chaplain67 was conducting service in the parish church, at 9 a.m., when bullets began to spatter on the walls, and the first cries of flying men were heard above the noise of breaking windows. At 10.30, the Prussian Guard entered the town, drums and fifes playing. Presently, with bodies of Saxons from Normée, they continued the pursuit, which proceeded more slowly toward Connantre and Oeuvy and the valley of the Maurienne. Here and there, small French groups turned at bay, because they could go no farther, or hoping to stem the retreat. Thus, 200 men of the 66th and 32nd Regiments came to a stand in one of the dwarf-pine woods south of Fère. They had no officer among them; but a sergeant-major named Guerre took them in hand, and disposed them in four sections, “like the square at Waterloo,” he said. One German attack was beaten off; but when a field-gun came up, Guerre decided that the only hope was to make a sortie. It cost the brave man his life. About 30 of his fellows got away, including two privates, Malveau and Bourgoin, who, after wandering in the German lines, and being directed by a dying German officer, brought the flag of the 32nd Regiment during the evening to the commander of the 35th Brigade.

Perhaps it was because of the convergence of roads upon Fère, noted above, that, whereas the original breakdown occurred on Foch’s right, the pursuit became concentrated upon his centre. The most important consequence of this fact was that the German Command never discovered the weakest part of the French front, and the dislocated right was able to escape from restraint and to re-form. The greater part of the 60th Reserve Division, which had extended from Vassimont and Haussimont to Sommesous, where two regiments arrested the Saxon advance for two hours, rallied early in the afternoon between Semoine and Mailly. General de l’Espée’s cavalry, with some infantry elements, held up a brigade of the Saxon XII Corps south of Sompuis; and the neighbouring army of de Langle effectively engaged the XIX Corps between Humbauville and Courdemange.

Westward of the main stream of pursuit, the position of Foch’s left was more delicate and critical. At the extreme left, we have seen that, during the morning, the 42nd Division recaptured Villeneuve and Soisy, while the Moroccan Division reached St. Prix and the Signal du Poirier. The 42nd held its gains throughout the day; but the 9th Corps, shaken by frontal attack across the marshes, and left with its flank in the air by the breakdown of the 11th Corps, had no choice but to withdraw its right, and suffered heavily ere it could take up new positions. Coming on from Morains, the Prussian Guard took the homesteads called Grosse and Petit Fermes, on the way to Bannes, in reverse by the east. Three French regiments were here thrown into confusion, cavalry plunging into the batteries, and fugitives obstructing the roads. The panic, however, was soon over. At 7.30 a.m., the retreat sounded; at 9 a.m., Moussy was reorganising the 17th Division on the line Mont Août–Puits, with the 52nd Reserve Division in support. Hither the faithful 77th Regiment was called from Mondemont during the morning to help form an angular front, across which the Germans passed south in pursuit of the scattered elements of the 11th Corps. The headquarters of the 9th Army were moved back from Pleurs to Plancy, on the Aube.

Thus, at noon on September 8, the shape of the vast battle was markedly changed. D’Espérey was on the Petit Morin near Montmirail, and his 10th Corps near Corfelix. From the latter point, Foch’s left extended south-east to Connantre. His centre, broken in to a depth of ten miles, was floating indefinitely in the valley of the Maurienne. The right, supported by de Langle, giving no immediate anxiety, his first problem, therefore, was to save the centre without losing the solidity of the left. It is in such emergencies, when a few hours even of loose and unsuccessful resistance may turn the balance, that the virtues of a race and the value of traditions and training in an army reveal themselves. The breakdown before Fère Champènoise did not degenerate into a rout. Eydoux pulled the fragments of the 11th Corps together on the line Corroy–Gourgancon–Semoine, and in the evening delivered a counter-attack which gave him momentary possession of the plateau of Oeuvy. Dubois aided this reaction by striking at the west flank of the German advance. Early in the afternoon, after a preparatory fire by 15 batteries near Linthes, the 52nd Reserve Division was thrown eastward toward Fère Champènoise. This effort failed, as did another in the evening; and Dubois had to withdraw slightly, first from Puits to Ste. Sophie Farm, then to Chalmont, while the Prussians held Connantre and Nozay Farm.

V. Fable and Fact of a bold ManœuvreThat evening, Foch conceived a manœuvre so characteristic of the man, so evidently after his own heart, that the facts of its execution have been hidden under a mass of sparkling fable. “If, by whatever mental vision,” the master had said in one of his lectures, “we see a fissure in a dam of the defence, or a point of insufficient resistance, and if we are able to join to the regular and methodical action of the flood the effect of a blow with a ram capable of breaking the dam at a certain place, the equilibrium is destroyed, the mass hurls itself through the breach, and overwhelms all obstacles. Let us seek that place of weakness. That is the battle of manœuvre. The defence, overthrown at one point, collapses everywhere. The barrier pierced, everything crumbles.” That it was Foch, not Bülow, who had been on the defensive makes no difference: Foch never thought of war in pure defensive terms. Now he saw his opportunity.

There was no subtlety in the object. A rush which fails to produce a complete breach opens a flank plainly inviting attack; and the Staff at Plancy had had its eyes fixed all day upon the new German flank, 6 miles long, from Mont Août to Corroy. Twice the 9th Corps had struck at it without success. The boldness of Foch’s design lay, not in its objective, which was evident, but in the means proposed for its execution. The right of the 9th Corps could do no more; its left, the Moroccan Division, had lost the south bank of the marshes, and was hard put to it to hold the hills around Mondemont. Nothing remained but the 42nd Division, which, though greatly fatigued, was in somewhat better posture about Soisy. Two demands now competed in the mind of the French commander. He regarded Mondemont as a key-position to be defended at all costs; and the removal of Grossetti, without compensation, would gravely endanger it. But more than in any position he believed in forcing a result by a well-directed blow when the enemy offered the chance. D’Espérey’s 10th Corps, it is true, had before it the chance of breaking across Bülow’s communications at St. Prix and Baye; it had otherwise no pressing call to make such a movement. Farther south, there were both need and opportunity—the need of relieving the 9th and 11th Corps, the opportunity of a decisive action. Grossetti, then, must come to Linthes, and d’Espérey’s 51st Division, in reserve of the 10th Corps, must take his place west of Mondemont. D’Espérey’s loyalty in agreeing to this arrangement cannot be too warmly praised. The comradeship of arms, so influential a factor in the victory of the Marne, was nowhere more admirably illustrated.

But dawn on September 9 broke upon a situation aggravated to the extreme, in which the projected manœuvre might well seem a blunder of recklessness. Bülow and Hausen had summoned their exhausted men to undertake a last essay. On the French left, Mondemont fell at 3 a.m. Two hours later, the Guard and the two Saxon Corps burst upon the centre and right with all their remaining force. Neither the 9th nor the 11th Corps was in a condition to meet this trial; but, in general, they faced it bravely. At 9 a.m., the 21st Division (11th Corps) could resist no more, and fell back from Oeuvy to Hill 129, south of Corroy, whence its commander, Radiguet, wrote to Foch: “My troops could not hold out any longer under a bombardment such as we have suffered for the last two hours. They are in retreat all along the line. It is the same with the 22nd Division. I am going to try, with my artillery and what I can gather of infantry, to rally on the plateau south of Corroy. My regiments have fought admirably, but they have an average of only four or five officers left.”